| "It's a question of creating another atmosphere of art. It doesn't matter who creates it."

Reflections of an Albanian Theater Artist

Part 4 in a series of articles "Creating Art in the Balkans" by Eloise de Leon

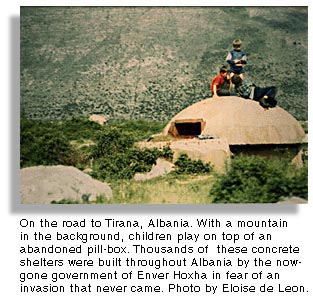

Introduction I traveled to Albania in May, 1996 with my hosts from 7 Stages (of Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.A.). Del Hamilton was meeting with a theater director and professor at the university in Tirana. Our visit was preceeded by warnings of highway criminals. But as we drove away from the enchantingly beautiful Skopja, Macedonia, we forged ahead with confidence in our plans. Crossing into the Albanian lands, although safe for us, seemed like traveling backwards in time. Modern life had somehow met with Albania in uneven ways, and the isolation of 41 years under the government headed by Enver Hoxha left the country still slow to find it's place in the global village. Our tour guide for two days was Yancy, an assistant director at the university. A couple of years earlier he had traveled to London on a fellowship to participate in a student theater course for a month. He told us how shocked he was to see the outside world for the first time -- so shocked that he was speechless for the first two weeks. He was afraid of how his lack of access to modern theater plays and theory had perhaps stunted him and would make him seem a fool. But then he decided to jump in and give it everything. What he learned left him with an exhilarating experience which now frustrated him. He could not, for the moment, determine how to leverage change in Albanian theater. National theater artists are placed on salary and it doesn't matter what they do after that. The incentive to learn, be creative or be challenged does not exist. Yancy did not foresee any possibilities of leaving the country after that, due to the impossible expense. Immigrating elsewhere was not a question. He wanted to stay with his family and to contribute to Albanian life. But the isolation of the country was depressing. Communication with the outside world was, in spite of the "open borders", next to impossible. In the theater courses the university did not have access to most contemporary plays known to the rest of the world. And mailing texts or videos was determined to be useless, because they were sure to be stolen in the mail. Now, two years after my trip, I am printing my interview with Yancy. Since all of the trouble Albania has had and continues to experience since 1996, I keep remembering his words. His mentor who was our main reason for visiting, has since moved to France. Eloise de Leon: As a director what would you say are the main problems in working with actors right now? Yancy: Working with national theater actors is not the work a director (outside of Albania) can understand. A director in Albania must be responsible for everything that happens on stage. That means choosing the play, talking with the scenographer, choosing the music sound track and creating -- from the beginning to the end -- the characters. The actors' duties, are to learn lines by heart and to follow the words of the director. That means that the actor is not allowed to create the character itself, or to develop it. That's not because of the directors. In Albania, the actor is waiting for the director to find the details, the artistic values of the character and even to raise, or not raise, the voice. How to say the phrase. We're speaking about monologues and the rest of it. So that's the problem. That's why it's so difficult to work with our actors. ... even if they were not black and white characters, they do it like that and then they direct like that, a kind of black and white exactly. In the future what I think we should do is, first of all, create a situation of having more than one theater with a reputation. This will create a quite different quality in theater. As much theater as we can create. Young generations being financed by the government or Soros itself -- doesn't matter, that's not important. The important thing is that people must go towards theater. Even the audience numbers are becoming lower and lower, even in the national theater. The audience doesn't have that much choice about the repertoire and quality. If I can create that situation, to have 2 or 3 shows in Tirana performed in the same hour, then maybe the audience will choose, will have the right to choose. That's very sound and very democratic and this will improve absolutely the quality of theater in Albania. There are no smaller theaters. It is actually the academy with it's student work which attempts to compete with the national theater. The government doesn't pay much attention to the academy because what they pay is the professors and the simple set of the play. The national theater is very expensive. It's not a question of government politics right now. It's a question of creating another atmosphere of art. It doesn't matter who creates it. It is a fact that they (national theater)are funded by the government -- nobody wishes to doubt that. But for instance, if the theater can say, hey, I can get 50% from the government and I can raise another 50%, what will happen? Then the government will not have more power in theater and theater will be a little bit flexible. The government doesn't care that much about what the theater will do. If they want to be independent they can be independent. The question is damn simple. I mean the government wants to have a bigger budget but give less to theater. It's not that interested in creating new theaters or doing new theater projects. They just keep the situation as it is because they are okay, they have their percentage of the budget and they can do that. Eloise de Leon: Can you talk about yourself as an Albanian in relation to other Balkan theater artists? Yancy: I can't say that there are a lot of relationships or conversations with Balkan artists. We don't have that collaboration to have that kind of conversation about the arts. That's the reality. All our contact with Balkan art is with our people who live in Kosovo. Kosovo is well known as an Albanian territory and population so all we've done is just share some ideas with Kosovo people about Balkans. We took part in one festival, a school festival, which was in Skopja, Macedonia. Balkan schools do come and take part. But for different reasons we haven't stayed at the festival for more than four days. That means one day to go, one day to rehearse, one day to perform and then off you go. So the contacts I can say are poor, very poor. Eloise de Leon: What has been your perception of the war in ex-Yugoslavia these past few years? Yancy: I'm an enemy to war and I don't quite understand the reason to make a war especially when it is in the Balkans. It doesn't make sense we are always in war and I don't know exactly right now, I don't know exactly who it was started that war, or why. I'm not quite sure. What I know is that in that war there is so much hatred, ... and I don't why all that exists. It's deep, it's very deep, the hatred now. It's quite deep and coming today from year to year from century to century. I don't know why, but it happened like that. Maybe I said to you before, the theory that I have about love? Maybe we, like all (people from) Balkans, we are not used to love. That's why maybe we're more open to hatred than to love each other. Maybe the economy has not allowed us ... I don't know, there are thousands of reasons why we hate more easily than we love. We were in Macedonia at a festival of art schools and it was Albania, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Serbia, Croatia, and some other schools of ex-Yugoslavia. Well, I saw a girl and I liked her very much but I never talked with her, maybe because I was Albanian and she was Serbian. We hadn't made any sign to each other. I mean I made no sign to her. Probably she didn't notice that I was looking at her or wanted to talk with her. I didn't make any sign. I was just thinking in that situation, it was horrible, somehow it was horrible, I couldn't talk with that girl just because of my being Albanian and she being Serb. We came from two nations that traditionally hated each other and fought each other. I don't know who started it first, I don't care about it, or who did it the wrong thing in the beginning ... maybe because of Kosovo, maybe because of other things, I don't know but I felt very bad. I felt very bad. I imagined for a moment, "Okay, you're going to talk to that girl, you're going to go to be with that girl. Okay, and then will you represent that girl? You will stay with her? And she will stay with you? And then your friends will look at that girl and immediately they might say something," Probably for all of my life I'll say the same thing -- not with our hateful histories, but with love histories, with communication, with just talking to each other, with just sharing something with each other. That's one of the reasons that our theater was not communicated, because we were not communicating with our neighbors first. Eloise de Leon: Your most recent interest has been in directing readings of love sonnets? Yancy: Why was I directing sonnets and choosing the love messages? I'm used to hate, like living with old relatives. So I decided to pour love, to everybody, love just love. No big messages, no ambitious messages. Not to teach somebody else what to do or how to do it, or what to do with his brain. Just love, just please do love. And that's the answer for a lot of questions between us and the rest of countries in Balkans. The exact answer. I might mention from the ancient times, us, like Balkans, get the most powerful tragedies ... that can live till now, but I don't think we have a love for example like Romeo and Juliet. We can get tragedies, very big, very good tragedies with a big problem in it. The power, where can it go, how can it go from one end to another. But nobody has written any Romeo and Juliet (here). That's why I need that kind of love for me and everybody else. I don't want to say who's right and who's wrong. Or who loves more and who loves less. The question is just to love, to love thy neighbor, to love thy parents and the parents to love you. Maybe to forget for an instance all the wars that we have done. I don't know why we have done that. Maybe to protect something. I'm not sure. I'm in doubt about everything, because I'm young. Sonnets are mostly for love ... it is pure crystal love. And given in that peculiar, gentle, not harmful sense, that's why I choose sonnets. There are a lot of artists who do things, they will give their messages a kind of ideology or politics. Actually even me, as I say, for love. I do my politics as well. It's not the question of using the word "love" like between a boy and a girl, it's wider than that. But that's the only word, love. You can cannot create other words. To love even a flower. To love and respect. Love is very connected to respect.

Eloise de Leon is an artist coach, writer and filmmaker currently living in New York. Her articles may be found in the Art Changes and Human Rights / Civil Rights sections of In Motion Magazine. Her website is: www.insightandjoy.com and her email is: eloisemargaret@gmail.com. |

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2020 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |