|

Chicano Artists and Zapatistas Walk Together

Asking, Listening, Learning: The Role of Transnational Informal Learning Networks In the Creation of A Better World Part 1: Network Learning by Roberto Gonzaléz Flores, PhD Los Angeles, California |

||||||

| The following is part one of a dissertation presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Southern California in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Education), August 2008. Footnotes and references will open in a new browser window for easy reference. For Part 2: Findings -- Centrifugal Motivation, visit here. | ||||||

The study shows that the 9 Chican@ artists were initially attracted to Zapatismo because of centrifugal negative experiences in the U.S. as they encounter institutional racism, social marginalization and exclusion from the social justice movements on the one hand, and positive centripetal identities and relationships that draw them towards Zapatismo, on the other. The Chican@ artists are critical of the traditional social justice organizations’ strategic aims to either reform capitalism or to take state power. The study shows that the Chican@ artists related to the Zapatistas through a centripetal positive learning process that includes ethnic cultural, spiritual and political affinities. This research demonstrates that the informal learning relationship between Zapatistas and Chican@s is inter-subjective or horizontal because the learning style is between persons that value their differentness. While this study agrees with Peter Mayo’s and Greg Foley’s research on transformative learning, it is implicitly critical of Paulo Freire’s approach given that the Freirean facilitator or change agent’s role evokes a directive rather than a horizontal method. This research implies that the artists’ echoing of the Zapatista message reinforced and enhanced the initial Zapatista call and has facilitated the initiation of a transformational paradigmatic shift within the Chican@ movement. One of the underlying premises of critical pedagogy is that state-sponsored education has historically served and reflected the ideological, economic and political needs of those in power (Gramsci, 1971; Apple, 1999; Esteva, 1992; Freire, 1993). Consistent with this premise, research shows that in the present global (neo) liberalization of capital and the globalization of market structures, formal and state-run non-formal education, such as adult education, work together with corporate forces, particularly media, to serve global market needs (Foley, 1999, 2004; Stromquist, 2000, 2002; Schugurensky, 2003; Walters et al., 2004; Apple, 1999). The role of corporate media, as informal education sustaining corporate control, can be seen in the appropriation of Orwellian progressive language such as “education for empowerment,” “decentralization,” “multiculturalism,” and “diversity.” This informal educational medium has become an important pedagogical strategy of corporate-based politicians intent on passing neoliberal policies. The neoliberal legal framework, in turn, has aided in shrinking the ideological spaces once enjoyed by progressive educators for contestation and reform aimed at democratizing education and society. At the top of today’s global market’s agenda and on the educational policy priority list of a growing number of countries are: privatization of education and social services, emphasis on efficiency business paradigms, cutting of the state’s contribution to education and the training and retraining of a global work force to meet its rapidly changing global market needs (Stromquist, 2002; Schugurensky, 2003; Walters et al., 2003; Apple, 1999). Globally Networked Informal Learning Castells (1997) and Gonzalez Casanova (2003) point out that in this era of globalized capitalism, domination, isolation, destruction and poverty are not the only social and cultural conditions that are globalized through networks. Gonzalez Casanova and Castells point out that a kaleidoscope of grassroots struggles are utilizing radical participatory democracy and informal education as their vehicles for change and are spontaneously combusting at local sites throughout the globe. Importantly, these grassroots struggles are not only utilizing informal learning methods internally but are also creating connections to each other in an ever-expansive informal learning network (Esteva, 1998). Learning through and in struggle through a practice-reflection-practice method, these struggles are learning to learn from others as well as learning how to share their experiences with others struggling in similar circumstances. This multitude of connections has extended beyond the local into the regional, national, and transnational and is boldly visible in the development and practice of anti-(corporative) globalization transnational movement of networked movements. Can Education Help Break or at Least Weaken these Monopolies? The demise of the Soviet Union, in 1989, signaled the end of the Soviet Bloc and the beginning of a new economic political era. Unfettered by the absent state-centered economy of the socialist sphere, gone the soviet military and political presence and its ideological critique and challenge, the capitalist venture has since vastly expanded its global reach. Although the influence and dominance of transnational corporations (TNCs) had been developing for some time, never has humanity seen the breath and depth of economic, cultural and political hegemony. Stromquist and Monkman (2000) respond to the overwhelming fact that globalization of capital is characterized by the monopolistic control of “technology, worldwide financial markets, global natural resources, media and communications and weapons of mass destruction,” with the question: “Can we [educators] change the nature of these monopolies?” and with, “Can education help break or at least weaken these monopolies?” (p. 20). In 1994, the Zapatista struggle, consisting primarily of indigenous people from Chiapas, the southernmost state of Mexico, introduced and presented a global challenge and contestation to globalized corporativism, to Mexico’s accommodating neoliberal policies as well as to the dominating role of the United States.(1) Esteva (2001), Zibechi (2003) and Holloway (2002) suggest that perhaps more important is Zapatismo’s profound questioning of the established reform-or-revolution paradigm that enveloped traditional social justice and liberation movements and their resultant fundamental aims, method and strategy, forms of organization and forms of struggle. Fourteen years have passed since the uprising, yet new Chican@ individuals and collectives continue to develop in Los Angeles continue to dialogue, struggle and learn hand in hand with Zapatistas through on-going and renewed informal learning connections and events. One of the initial and most important exchanges and dialogues occurred in the summer of 1997 at the Encuentro Chican@-Zapatista. This encuentro took place between over 120 Los Angeles based artistic youth and several hundred Zapatista representatives. This proposal plans to initiate the research with a close examination of the preparation, actualization and the follow-up to the encuentro, as told by its participants. From the examination of the encuentro the plan is to move to the localized expressions of what was learned in the lives of the artists and those they have impacted. My hope is that this study can help uncover the role of informal education through a transnational network relationship as a response to the globalization of capital. To accomplish the above stated goals this research will be guided by addressing the following general questions:

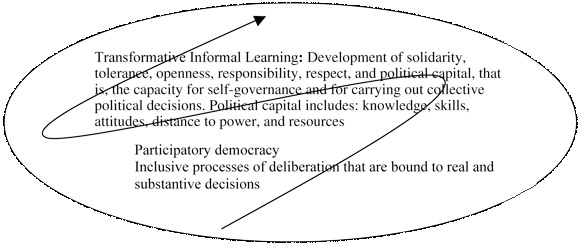

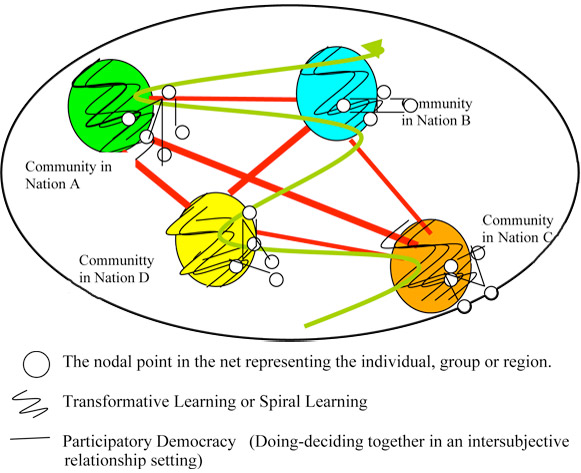

Organization of the Proposal I have organized this proposal into three distinct parts: The first part is dedicated to introducing the subject of network learning as an expanded form of informal learning. In the second part I will review the literature through a discussion of major theoretical constructs used to frame this research on informal education and network learning. In addition, I will discuss the macro political backdrop of corporative globalization, the significance and nature of Zapatismo as a pedagogical network movement, the Chican@ Movement and its connection to Zapatismo. In the third part I will establish the purpose and significance of the study and layout the proposed design of the study, justify its use, and present the method proposed for gathering and analyzing the data. Theoretical Framework and Review of Literature There are two major constructs that need theoretical scaffolding: informal network learning and transformative learning. Foley’s extensive research of informal education becomes particularly important to support and explain the general notion of “informal network learning.” In terms of “transformative learning,” Daniel Schugurensky’s research on the subject informs this study and helps to frame it theoretically. There are five theoretical constructs that frames this research: 2) A conception of education that emphasizes the relationship of education and learning and collective emancipatory struggles; that is, struggle for people’s right to exist as different (Foley, 1999). 3) A conception of education that includes transnational network learning as an increasingly practiced expanded and linked form of local collective emancipatory struggle. 4) A conception of education that looks at the role of artists as a critical sector of organic intellectuals (Gramsci, 1971) reflecting learning, provoking reflection, and facilitating learning through their art. 5) An analytical framework that allows connections to be made between learning and education and analysis of the overarching macro-political economy, the local micro-politics, ideologies and discourses among and between different struggles (Foley, 1999). I have added to Foley’s theoretical framework for researching adult education articulated in his book Learning in Social Action: A Contribution to Understanding Informal Education (1999) four important dimensions: the conception of network learning, the inclusion of the view of Chican@ artists as one group of many types of organic intellectuals that initiate and facilitate the informal learning process. In addition to the analytical framework which Foley borrows from Sonia Alvarez, (2) I add the conception of network learning as a transnational form of informal educational intervention and an analysis of globalization and global situation as part of the macro context. Lastly, while Foley’s work has been focused on adult learning, this research includes participants as young as their mid teens at the time of the encuentro. Below, I discuss each of the framework components further. Emphasis on Informal Education Foley (2004) defines informal education as “the sort of learning that occurs when people consciously try to learn from their experiences” (p. 4). Ironic and interesting is that significant anecdotal evidence and empirical research show that it is the informal and incidental learning within the formal educational experience that is best recalled. Darder (1991) for instance, points out that what is really learned from formal schooling is how to obey and serve a system poised to exploit and give orders. Learning Through Collective Struggle According to Foley (1999), it is important to view learning and education as a complex, diverse contextualized and contested activity. Foley (1999) points out that history can be seen as a series of struggles (contestations at different levels) between those that need to and want to dominate and those that learn to struggle against and resist domination and thus strive for emancipation. Part of the struggle is learning effective strategies on how to counter (contest) the discourse (ideology) sustaining and justifying that domination. Struggle for emancipation includes ideological, organizational, and political aspects. Foley (1999) further argues that the complexity of learning on the part of the people being oppressed includes learning strategies that consist of temporary compromises and some compliance mixed in with resistance as well as with proposals to reform the system. Although Foley’s primary research is informal education and looks at the global context within which this is occurring, his research does not include informal education within global learning networks. Most of what Foley and Schugurenski examine is what happens within a group within a particular struggle and not what happens between groups in struggles, including what is shared and learned between two different groups in different countries. Thinking of informal education as both a local and a global process expands educators’ understanding of how common people are learning to struggle on a daily basis. The informal learning network, as applied in popular struggles for social justice, such as the anti-globalization struggle, although aided by different technological advances, is not just a technological result, but seems to be a world view; one that acknowledges the interconnectedness, interdependence, and equality that exist between peoples and struggles. Network learning seems to allow the possibility that emancipatory struggles throughout the globe will not be carried out in isolation and that struggles in one part of the globe can serve to strengthen struggles occurring elsewhere. (5) Gramsci’s (1971) conception of counter hegemony evolved from the need to develop and articulate a response to the hegemonic narrative to make explicit hidden subtle forms of control. Gramsci’s assumptions and research showed that no matter how dominating a state was, it could not sustain forceful domination of its people (Burke, 1999). In an interview by Luis Hernandez Navarro, (2002) writer Arundhati Roy agrees with Holloway stating that future hope rests in the arts. Roy states that it is the artists, poets, and singers that are most capable of offering a new space for a new common sense, one where the “invisible becomes visible, the intangible tangible, the impalpable palpable” (2002). Hernandez who has written and researched extensively on the connection between rock, hip hop, and Zapatismo, points out that Zapatismo (2003) was born in the theatrical, in the arts, with Sub-comandante Marcos becoming an internationally renowned poet and literary personality. Castells (1997) refers to the use of staging, masks, pipes, and theatrics as a centerpiece of the communication genius of Zapatismo. The Relationship of the Macro, the Micro, and Informal Learning The theoretical framework used in this proposal needs to include a way of making the relational connections between education and learning, and the macro political economic (that includes both national and international) and micro or local manifestations. Because of the expansive possibilities of network learning, the temptation to want to create a universal model of struggle is powerful. Zapatistas will however warn “don’t follow us, we are developing our theory about the conditions facing us in southeastern Mexico, from our practice” (Marcos, 2003). Marcos (2003) makes this observation about the relationship of theory and practice: In our theoretical reflections we talk about what we see as tendencies, not consummated nor inevitable facts. Tendencies, that have not only have not been converted into hegemonies and homogenies that cannot be (and should be) reversed. Our theoretical reflection is usually not about ourselves, but about the reality in which we move. And its character is one that is approximate and limited in time and space in its concepts and in the structure of those concepts. That is why we reject any pretensions of universality and perpetuity in what we say and do. The answers and questions about Zapatismo are not in our reflections and theoretical analysis, but in our practice. And, in our case, practice has a strong moral responsibility, ethic. That is to say, we strive (not always successfully, …) to act not only according to our theoretical analysis but also according to that which we consider to be our duty. We try to be accountable, always. Perhaps that is why we are not pragmatists (another way of saying “a practice without principles”). (6) The demise of the Soviet Union and the disentanglement of its sphere of influence opened up an entirely new era, one of unregulated domination of globalized capital; one in which it is expected that formal education play a major part in its construction and one in which informal network learning is being called to play a counter-hegemonic liberating role. Brief Historical and Political Context of Zapatismo Zapatistas’ argue that the impoverishment and drastic decline in the quality of life, particularly of Mexican indigenous and among the campesino population, has been brought about by the confluence of corrupt government, increasingly stringent neoliberal austerity programs as well as unfair international trade agreements such as the North American Fair Trade Agreement (NAFTA) (CCRI, 1993). Critics point out that this combination of national and supra-national systems has provoked responses such as the 1994 Zapatista uprising in Chiapas and the appearance of the Ejército Popular Revolucionario (EPR) in Guerrero, Oaxaca and Morelos (Ross, 1995). In 1997, CIHMA (Centro de Investigaciones Históricas de Movimientos Armados) researchers pointed out that in addition to these two better-known groups there existed at least 12 other self-proclaimed armed groups throughout México. (7) On January 1, 1994, a relatively small army of indigenous peasants from the state of Chiapas, in Southern Mexico, came into the world's view when they seized six municipality seats, including the mythical colonial Jovel also known as San Cristóbal de Las Casas. On that day the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN), now often referred to as “EZ,” demanded changes in the Mexican economy and political structure, which would guarantee increased democracy and self-determination for the Mexican people, in particular indigenous groups. (8) The Evolving Nature of the Zapatista Movement From the onset of the current movement, the Zapatistas have developed their views based on a massive experiment in dialogical participatory democracy, sharing, gathering and exchanging perspectives and reflections with millions of people in Mexico and throughout the globe. Since January 8, 1994, eight days into the fighting, the Zapatista Army has not fired a single bullet in spite of hundred of incursions and killings by auxiliary paramilitaries under the direction and leadership of wealthy landlords and military forces. Since that historic moment, the Zapatista Movement began a process that eventually transformed them into a globally networked pedagogical movement that has had impact far beyond its initial miniscule size. Today, Zapatismo, with its approximately 2000 autonomous communities, stands as a case of a globally connected local response to the ill effects of what the Zapatistas call neoliberalism. Zapatismo can be understood as a transformative pedagogical approach for four reasons: (1) it is a new and necessary critical ideological, political, and organizational intervention (Freire, 1970; Stromquist, 1996; in Rolland, 1996) contesting the status quo, (2) its goals and means are focused on the creation of liberated spaces embodied by the autonomous community which is constructed by a learning of democratic participatory principals and methods, (3) because Zapatismo does not rely on reforming or forcibly replacing a corrupt regime and is therefore a challenge to traditional ideas of how to address social injustices, (4) because the Zapatistas transform themselves through a method of practice-reflection-practice. The Civil Society Revolution Brief Background of the Chicano Movement The definition of Chican@ movement is extremely problematic. My own definition is no less simple: The Chican@ Movement is an amorphous and fluid complex social justice movement within the United States borders, reflecting the coexistence and coalescing of several socio-economic classes with common ethnic, cultural, and historic roots engaged in a common struggle against the inhumane treatment and general oppression of people of Mexican and Latin American descent. Garcia (1997) argues that Chicanismo is more of a political sentiment than a nationality, ethnic group, or ideology. Because of the variegated political tendencies and trends on both side of the United States-Mexico border, not all Mexican economic refugees living in the U.S. identify with Chican@s in their political orientation. On the other hand, self-included in the Chican@ political movement are many Latinos from Latin American countries other than Mexico, who fall into the historic pattern of oppression, and perhaps because of that identify with Chican@ politics and ethos of resistance. (11) The definition utilized in this proposal also attempts to include the cultural and political sentiments and sensibilities brought in by ever growing numbers of recent immigrants. Some people who today consider themselves Chican@s (Californios, Tejanos, and New Mexican and Colorado Manitos) were never part of a consolidated and independent Mexican state; that is, these groups of Chican@s are indigenous to colonial Spanish land grant territories and post independence (1824) Mexican territory that is now part of the US and they never migrated to the United States. While some Chican@ people come from migrants that crossed pre-1848 undefined and fluid national borders, and others are indigenous to these lands, the vast majority of Chican@s can trace their ancestral roots to post 1848 crossings with the thick of population descending from post 1960 migrations. Although concentrated in Southwestern US territory, annexed by the US between 1845 and 1848 (Acuña, 1969; Powers cited in Sanders, May, 2002), today Chican@s can be found in growing numbers in almost all states of the United States (Ramirez & Therrain, 2001). (12) A recent report by several Spanish speaking newspapers citing published research conducted by the Mexican Secretary of the Interior states that at least 600 Mexicans successfully migrate to the US on a daily basis which adds up to 2,000,000 per year (Ensino La Jornada, 27 de April, 2004). Between 1514 and 1824 Mexico was a colony of Spain and many Chicanos view their second-class citizenship status, the discrimination, and immigrant status in the US tied to successive systems of oppression: Spanish Colonial rule (1514-1824), US imperialism and today global neocolonialism (1836 to present). (13) The dire historic economic situation in Mexico is commonly referred to as the “push factor” that results in the constant and increasing flow of what Marcos calls “human export.” (14) The “pull factor” refers to the insatiable need for cheap labor of US agribusiness, textile industries, and service sector, to name a few, as well as the support provided by relatives and friends that are already in the US, alleviating the difficulty of an illegal passage and extra-legal existence. Once in the United States, Chican@s resist total assimilation by persisting on practicing their traditional ways of knowing, language, and culture as they are pressured to abandon Mexican ways by what many consider to be a Euro-centric US culture and political economy. Similar to the indigenous of Mexico, Chican@s along with Blacks and Native Americans are culturally, socially, and economically at the bottom-- the most marginalized. The cultural, national, and political identification between Chican@s and indigenous seems to be the basis for further openness, for shared communication and the basis for further articulation of a common social political economic analysis. This initial identification becomes part of the bridge for a new and different type of solidarity, which the Zapatistas call “walking together.” Walking together includes supporting each other as equals and learning from each other (Marcos, 1992). (17) Historically, artists in the Chican@ movement have played an extremely important role in not only reflecting the struggles but in guiding them (see Center for the Study of Political Graphics). (18) Many of the Chican@ artists simultaneously reflect a microcosm of an undeveloped and repressed state as well the particular class and political interest of the artist. Broyles-Gonzalez (1994) recounts the role of the Teatro Campesino in the mid 60s, and its impact on the Chican@ movement. Today, we are experiencing a second cultural renaissance of artists that were not only influenced by previous movements but that are also critical of them. Born in the early 1990’s, the new Chican@ renaissance is more broadly inclusive in that it destabilizes the male/female heterosexual domination with the growing open participation of gay and lesbian expressions and embraces the sensibilities of poets, writers, and artists such as poet Cherrie Moraga, writer Gloria Anzaldúa, poet Luis Alfaro, muralist Alma Lopez and performance artist Gregory Ramos, to name a few of the more prominent openly queer artists. Related to this sentiment, my personal reason for the use of “@” mark is not only as a symbol closely connected to the cybernetic element in Zapatismo but that it began while I was in Chiapas in 1996 to be not only inclusive of both male and female but, given its likeness to a “Q,” I here use it to include the queer community. The Chicano-Zapatista Relationship On the 3rd of January, 1994, three days into the Zapatista uprising, a delegation of 12 Chicano human rights activist including myself, UCLA biochemist, Prof. Jorge Mancillas, Prof., and (now California senator) Dr. Gloria Romero, actress and playwright Maria Elena Fernandez, and human rights lawyer Evangeline Ordaz were frantically organizing to make our way to San Cristóbal, Chiapas. This was in response to the global significance of the uprising as well as to the immediate and intense affinity that Chicano activists felt to the Zapatista Indigenous uprising. There was one other Chicana, C X (19) who had been already networking with the Zapatista communities prior to the uprising via their academic work and participation with NGOs. It was these initial contacts that set the stage for multiple channels of communication with Zapatistas and their supporters. Summary While the overall purpose of this study is to examine network learning as a dialectical symbiotic relationship between Chican@ Arts Movement in Southern California and the Zapatista Movement, the specific objectives that serve this purpose are: The potentially independent position of informal learning through struggle allows it to freely imagine grassroots possibilities for a new world. Informal education as reflection of struggle in and among movements for social change is much less obstructed or restricted by government budgets, policies, and therefore able to freely develop as a space of creative critical thinking. Gramsci (1971), as other critical pedagogues today, brings out the importance to continue resisting the closing of liberated and autonomous spaces within formal and non-formal education. However, the level of privatization and corporate domination of formal and non-formal education (Stromquist, 2003) has provoked the importance to incubate, privilege, and develop informal learning which can in turn inform and strengthen those working within the formal and non-formal systems. Progressive changes within the formal educational system have historically depended on the work and perspectives of the informal educational experiences of grassroots movements, such as the civil rights movement and the movement for multicultural education. Today’s tight corporate grip on formal education seems to be prompting a growing number of grassroots movements not to depend, or expect much change from the formal institutional area. Under these conditions grassroots learning seems to be moving away from exploring how to change the formal system and instead moving towards creating innovative changes to be kept, practiced, and developed by and for the local. Gustavo Esteva (2001) points out that during the era of neoliberal politics people everywhere, not only in Mexico, have become increasingly disillusioned with the ballot box and have naturally tended toward direct democratic participation. The Zapatistas, Esteva argues, provide the possibility that people take their destinies into their own hands and create a new and legitimate grassroots body politic. Indeed, it has been my initial observation that, through the Zapatista communication method of reflecting and sharing their experiences through encuentros, consultas, email and the Internet, it has been possible to contemplate on and learn from Zapatista reflections and actions. Global Network Transformative Learning

|

||||||

| Published in In Motion Magazine August 15, 2008. |

||||||

Also see:

|

||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2015 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |