|

Single-Sex Schools for Black and Latino Boys:

An Intervention in Search of Theory by Edward Fergus, Katie Sciurba, Margary Martin, and Pedro Noguera New York, New York |

|

| In recent years there has been growing concern over the so-called "achievement gap" -- the pervasive disparities in academic achievement between Black and Latino students and their White counterparts. Since the enactment of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) in 2001, the achievement gap has emerged as a major priority among educators and policymakers, and has led to a search for sustainable strategies that might improve the academic performance of students who consistently lag behind in academic outcomes. Primary among these are Black and Latino males who conspicuously are over represented on most indicators associated with academic failure. While there are many other groups of students also likely to under-perform in school -- English language learners, students with learning disabilities, students from low-income families generally -- the vast array of negative outcomes associated with Black and Latino males distinguishes them as among the most vulnerable populations.

Black and Latino males are more likely to obtain low test scores and grades, less likely to enroll in college, and more likely to drop out, to be categorized as learning disabled, to be absent from honors and gifted programs, and to be over-represented among students who are suspended and expelled from school (Gregory, Skiba, and Noguera 2009). The ubiquity of these patterns, and the ominous implication of these trends on the long-term life chances of adult Black and Latino males has led to a growing chorus that something must be done to intervene. However, while the problems are clear and undeniable, their causes are murky and complex. Race and gender set this vulnerable population apart, but it is not clear what race and gender have to do with the broad array of academic and social problems they face. Lack of clarity around the causes has not prevented those who seek to help Black and Latino males from taking action. In the last few years the creation of single-sex schools has been embraced in various parts of the U.S. as a strategy for ameliorating the risks and hardships commonly associated with the academic performance and social development of Black and Latino males. Following the amendment changes in NCLB in 2002, there has been rapid proliferation in the number of public schools offering single-sex education. In 1999, only four public schools offered single-sex education. By 2006, there were 223 public single-sex schools. Despite this dramatic increase, the research supporting the benefits of an intervention that isolates males from their female peers is sparse and at best inconclusive. Nonetheless, policymakers and educators have begun to embrace all-male schools and classrooms for Black and Latino males as an intervention they hope will solve some of the problems these groups of children face. Existing research on single-sex education has primarily focused on how it differs from more common co-education schools and classrooms with respect to the strategies and practices that have been employed. Additionally, some research has focused on whether single-sex education results in statistically significant improvements in achievement as compared to results obtained in co-ed classes. Within this limited body of research the emphasis has been on the following variables: the type of subject matter (i.e., English, Science, etc.), teacher experience in implementation, the organizational elements of single-sex schools (e.g., school size, course offerings, climate for learning, leadership, etc.), student prior achievement and background, sex-role stereotyping, and student confidence and engagement (Bracey, 2007; Malacova, 2007; Riordan, 1994; Riordan et al., 1995; Salomone, 2005; Spielhofer et al., 2002; Mael, et. al, 2005). Interestingly, none of the limited number of empirical studies examine the viability of single-sex education or offer clear guidance related to “best practices” with respect to how education should be delivered or how such schools and classrooms should be managed and organized (e.g., Carpenter and Hayden, 1987; Gillibrand et al, 1999; Lee and Bryk, 1986; Marsh and Rowe, 1996; Marsh, 1988; Spielhofer, et. al., 2002). Most importantly, the research on all-male schools is limited by a lack of attention to how assumptions about gender (i.e. what boys need) and their development influence the decisions to separate boys and underlie the choices in teaching and learning practices and classroom management techniques. This paper draws upon data collected in a three-year study of seven single-sex schools, however only five are discussed in this article. The goal of the study was to document what these schools were doing to address the academic and social needs of their students, and to assess their impact upon student outcomes. Through collection of qualitative and quantitative data, the "Black and Latino Male School Intervention Study" (BLMSIS) has sought to provide an empirical foundation that might be used to inform public policy related to the development of single-sex schools for males in the US. For the sake of this paper, our focus will be limited to an examination of the ways in which assumptions about race and gender have informed educational practice and its implementation. In the analysis that follows, we make these assumptions and the composite theory of change explicit in the hope that by doing so we will be in a better position to determine whether or not this is what educators, parents, and policy makers want to pursue for young men who, in many cases, are in desperate need of assistance. "Saving the Boys: How Discourse on the Problems Confronting Black and Latino Males has Influenced Research Before examining the theory that has guided the development of single-sex schools for males as an intervention, we want to situate our research within the existing explanatory research discourse regarding the education of Black and Latino males. Existing research has primarily focused on the behavior of Black and Latino males and the factors that influence educational outcomes (e.g. dropping out, delinquency, achievement patterns, etc.). As is true with much of the social science research on poor people in the US, this research has been divided between scholars who emphasize cultural versus structural explanations of social behavior. Advocates of cultural explanations tend to argue that Black and Latino males adopt attitudes and norms that increase their proclivity to delinquency and academic failure. For example, Harvard sociologist Orlando Patterson made the argument not long ago in an editorial in the New York Times (March 12, 2006) that Black males maintain a disposition or “a cool pose” that contributes to anti-social behavior and is non-conducive to academic success and positive educational engagement. Likewise, scholars, such as Richard Majors (1993) and John McWhorter (2003), and journalists, such as Juan Williams (see Williams, 2006), have emphasized “gangster rap music, anti-intellectualism, misogyny” and a host of other negative cultural influences as a primary cause of the problems confronting Black males. In contrast, a small but significant number of social scientists have posited that certain structural conditions, namely de-industrialization in urban areas, racial discrimination in the labor market, tracking, and other forms of inequality in schools, contribute to the marginalization of Black and Latino males (Wilson 1987; MacLeod 1987; Bourdieu and Wacquant 2001; Noguera 2002). Such scholars emphasize the importance of understanding how the marginalization of inner-city youth is perpetuated by larger macro-level forces (i.e. the exodus of jobs and opportunities), and how such changes give rise to individual nihilistic attitudes and anti-social behavior. Negative attitudes and actions are symptoms rather than causes of the problems affecting disenfranchised males, and for this reason, these scholars emphasize the importance of addressing joblessness, concentrated poverty, overcrowded, failing schools, inexperienced teachers, and police brutality, in their recommendations for what should be done by policy makers. Epidemiologists and psychologists have identified a number of risk factors within the social environment that, when combined, are thought to have a multiple effect on the risk behaviors of Black and Latino males. Lack of access to health care, adequate nutrition, and decent housing, growing up poor and in a single-parent household, being exposed to substance abuse at a young age, and living in a crime-ridden neighborhood are some of the variables most commonly cited (Earls, 1991). Similarly, anthropologists and sociologists have documented the ways in which certain cultural influences can emerge in impoverished communities and contribute to lower aspirations among Black males and the adoption of self-destructive behavior. Anthropologist John Ogbu (1987) argues that "folk theories" in many Black communities convey a sense of hopelessness to Black youth. He argues that many adults believe that, because of a history of discrimination against Black people, even those who work hard will never reap rewards equivalent to Whites, and that this perception of a glass ceiling contributes to the adoption of self-defeating behaviors (Ogbu, 1987). Other scholars have suggested that many Black and Latino males view careers in sports or music as more promising routes to upward mobility than academic pursuits, due to a lack of role models who have used education to secure professional jobs (Hoberman, 1997). Among Latino males, gangs are viewed as providing better opportunities for mobility in communities where gangs have been entrenched for many years and even generations (Vigil, 1988). Despite their importance and relevance to academic performance, risk variables and cultural pressures cannot explain individual behavior, particularly for those who manage to avoid negative outcomes. Confronted with a variety of obstacles and challenges, many Black and Latino males still find ways to survive, and in some cases, to excel. Since 1970, the number of Black and Latino males enrolling in college has risen steadily (U.S. Department of Education, 2009) and while it has not matched or kept pace with that of Black and Latino females or White enrollment patterns, these trends should not be ignored. Interestingly, while we know a lot about those who succumb and become victims of their environments, we know much less about the resilience, perseverance, and coping strategies employed by individuals who succeed, despite the fact that their lives are limited by hardships. Deepening our understanding of how individuals cope with, and respond to, their social and cultural environments is an important part of finding ways to assist Black and Latino males in living healthy and productive lives. Unlike the research on urban poverty, the theoretical and empirical literature on single-sex education is mixed, and research on all-male schools, in particular those that serve boys of color, is extremely limited. Surprisingly, this is the case even though single-sex schools have been around for hundreds of years in the private and parochial school systems. The research on single-sex education has primarily focused on whether it differs from co-education with respect to form and content, and whether single-sex education results in statistically significant advances in achievement as compared to that obtained in co-educational settings. Some of these key studies are described below. Research on the effectiveness of single-sex classrooms and schools offer mixed results. Marsh and Rowe’s (1996) study of the effectiveness of single-sex classrooms randomly assigned boys and girls to single-sex and coeducational classes within a school and examined changes in achievement among the groups over a one-year period. The authors found no evidence supporting an academic advantage for the single-sex classes. Similarly, a number of studies on single-sex schools found that when controlling for student background, these differences between single-sex versus co-educational schools disappear (Daly and Shuttleworth 1997; Harker, 2000; Jackson and Smith 2000; Robinson and Smithers 1999; Steedman 1985). A number of studies, however, found that while single-sex classrooms led to significant increases in academic achievement for girls, there was no increase for boys. For example, in their study of single-sex science classrooms, Carpenter and Hayden (1987) compared single-sex Catholic versus co-education public high schools for males and females. The authors found that girls in single-sex schools performed significantly better on exams across all subject areas than their female peers attending coeducational schools. However, the authors found no evidence that attending a single-sex school had an effect upon achievement for males. Similarly, in a large- scale study of single-sex secondary schools in England, Spielhofer, O’Donnell, Benton, Schagen, and Schagen (2002) found that females in single-sex schools performed significantly better than females on all-subject achievement test scores, and their findings were significant in favor of single-sex schools; however, again there were no significant differences in test scores for males in single-sex or coed schools. That said, their multi-level modeling approach revealed some significant performance gains for students of lower prior all-subject achievement test scores in single-sex schools. It must be pointed out that in addition to the dearth of empirical examinations comparing single-sex and co-educational school settings, these existing studies are also fraught with methodological and analytical limitations (Mael, et. al, 2005). First, much of the existing research on the impact of single-sex instruction has been limited to small-scale studies, studies of single-sex private and/or parochial schools, and studies outside of the U.S which may not be generalized to US public school settings. Moreover, many of the studies either do not include co-educational school comparison groups or do not adequately address the issue of selection bias. Finally, several of the studies do not explore social interaction factors and social context development variables, which could explain the variation in single-sex outcomes (Bracey, 2007; Mael, et. al, 2005; Malacova, 2007; Riordan, 1994; Salomone, 2006; Spielhofer et al., 2004;). The variation of outcomes between schools and students may be explained by the extent to which the single-sex classroom may be utilized as a resource, giving attention to gender role ascription and perceived gendered norms of interaction between teachers and students, and/or no change in instructional and social interaction practices (Cohen, and Ball, 2003; Finn and Achilles, 1999; Hattie, 2002; Martino and Frank, 2006). In sum, much of the research on the benefits of single-sex schools is mixed, with the notable exception of schools focused on the needs of girls. The existing research on girls in single-sex schools points to a pattern of significant gains in academic achievement. A possible hypothesis for why the research is bearing out such positive patterns may have to do with the theoretical underpinnings that have guided the development of all-girls schools. According to Datnow, Hubbard, and Mehan (1998) who carried out a qualitative study on ten male and ten female single-sex academies in California, the educators who created educational programs for girls did so with an explicit desire to disrupt and dismantle the gender-based stereotypes, roles, and expectations that informed the education and treatment of girls in co-educational settings (Datnow and Hubbard 1998). The authors conclude that the desire to free girls from limiting gender roles led them to create schools where girls were encouraged to partake in leadership and to achieve in math and science, areas where girls have historically performed less well than boys, and to play sports and participate in other traditionally male activities that seemed to mediate positive achievement outcomes. On the other hand, the educators who designed the all-male academies did so with the assumption that what boys needed was stern discipline, rigid structure, and a highly competitive learning environment. Datnow and Hubbard also noted that although the educators who designed these academies never met together or communicated with each other about the kinds of programs they sought to create, their schools were surprisingly similar. Our own research on single-sex schools leads us to believe that these similar approaches are more than just a coincidence and in fact serve as further evidence that assumptions about gender (and as we shall show race and class) are so pervasive and commonplace that they easily become embedded within the theory and practice guiding the development of single-sex schools, unless they are deliberately exposed and contested. Methods To capture data on the overarching theory of change guiding the schools’ work in our sample, we draw from data from 75 interviews and focus groups with administrators, teachers and parents collected during these two waves of data collection. Semi-Structured interview protocols captured principals’ and other key administrators’ perceptions of implementation, knowledge and satisfaction with intervention, and their theory of change, practice, and schooling and community experiences. The focus group protocol captured parents’, teachers’, and other stakeholders’ knowledge, expectations, satisfaction with the intervention schools, and schooling and community experiences. In addition, we collected and reviewed a number of school artifacts including official state or city issued school reports, internal and external documents, and each school’s website and promotional materials. Data Analysis:

The intention of this analysis plan was to construct the theories surrounding the goals, expected outcomes and indicators related to the development and implementation of each single-sex school. Thus, the unit of analysis is at the school level. Expected outcomes (goals) were analyzed through a series of deductive and inductive analyses. First, the above codes were used to conduct deductive analysis within a data matrix that allowed for within-case and across-case analysis (Miles & Huberman, 1984). The initial deductive analysis involved categorizing the data by school and examining the data from that vantage point. The data were then examined along four categories that emerged from the initial analysis: school climate, teaching and staffing, student needs and challenges, and community context. These categories contained various areas of emphasis (e.g., school climate focused on the role, need and mission of the school, strategies embedded in school practice, etc.).The within-case analyses focused on identifying the emerging themes within each category for each interview and focus group within each school. An inductive analysis process was also conducted; this process involved taking the emerging themes and re-inspecting the data, modifying predetermined codes, and constructing new codes (Miles and Huberman, 1984). Thus, the purpose of these coding and analysis patterns was to encourage a recursive process of deductive as well as inductive coding and interpretation throughout the analysis. School Descriptions Findings

Identifying the Educational Needs of Black and Latino Males: Much is written about the context of the school environment and its relevance in setting tone and trust (Bryk and Schneider, 2003), caring (Noddings, 2005; Valenzuela, 1999), and academic engagement (Suarez-Orozco, et. al., 2008). When asked about the purpose and need for single-sex schools focused on Black and Latino boys (or “Boys of Color,” a term the schools often use interchangeably with “Black” and/or “Latino”), administrators unequivocally discussed the various social/emotional and academic issues facing Black and Latino males as framing their school designs. In order to achieve the goals of deeper student engagement, caring, and trust, which are believed to contribute to higher academic and life success rates, each of the single-sex schools in this study emphasized the need to “undo” or “address” cultural and structural damage or inequities that have prevented Boys of Color from closing the achievement gap. While in their missions, some schools emphasized the boys’ perceived social/emotional needs and others emphasized their academic needs, each of the single-sex schools were framed as providing students with an alternative to what they had been exposed to in more traditional public schools or in their wider societal spheres. Changing Notions of Masculinity

North Star’s response to the absent male problem is to find “mentors to serve as ultimate role models for young men” to alleviate some of the “anger” associated with not having a father figure. The boys’ perceived anger manifests as issues dealing with “authority,” which teachers at North Star admitted they are “not equipped to know how to fix” because this problem, they expressed, is deeply rooted within the boys. These schools conceive themselves as mechanisms through which young men of color develop an alternative masculinity that runs counter to stereotypical “street,” images that tend to keep them from being successful. In other words, the boys are being taught not to be the kind of man stereotypically associated with the communities poor Black and Latino males often come from. At Thomas Jefferson School, the staff in a focus group described the debilitating effect of not having positive images, specifically for Black boys:

The masculine identity the school would like to nurture is one in which boys embrace activities that they may perceive as feminine and shift their focus away from a masculine identity centered on sexual prowess. The teachers at Thomas Jefferson describe this desire in the following quote:

Exposure to negative male influences is manifested in what some school staff present as a battle between students’ home lives and their school lives. The school-community liaison of Westward, for example, explains:

The counselor at Westward concurs with this struggle, particularly as it relates to what he perceives as the mixed messages of masculinity the boys are getting at home and what is possible at school.

Changing Notions of Being a Black or Latino Man According to key administrators at North Star, the goal of the school is to “help” young Black and Latino men “realize that what they see out there in the streets” (drugs, gangs, violence, etc.) is not the only option for them. The negative external influences, such as community dynamics and popular Black culture, these administrators reported, inhibit the boys’ abilities to move forward educationally. In addition, the boys are viewed as susceptible to peer and cultural pressures that tell them, according to the principal, “It’s not cool to be smart.” At Salem School, the administrators identify individual and societal issues that they see as operating in an interactive fashion that presents challenges for their students. At the individual level, an “identity crisis” is conceptualized as a core challenge that is multifaceted and affects the students’ racial, gender, and academic identities. Racially, a key administrator highlights how “students are bombarded with imagery and the identity of being a thug, being a gangster, being hard,” defining what qualifies one as a man. Various school staff across the schools also noted the need for a masculine identity is due to structural impediments like racism. The college counselor at Westward described the presence of this structural force in the challenges faced by boys of color:

Administrators and staff across schools also describe the presence and operation of this institutional racism in what they express as the lack of normal developmental opportunities available to boys of color in comparison to White boys. For example, at Thomas Jefferson, one school staff member described missed developmental opportunities:

Becoming an Academically-minded Black or Latino Man The school staff also framed the lack of a positive masculine identity as bound to a lack of academic identity. The principals discussed the influence of society’s definition of masculinity, where an “identity as a learner isn’t something they value as [much as] an identity to be tough or what it means to be a man.” This socially constructed disconnect between “what it means to be a man” and what it means to be a learner is considered to present a real challenge for the schools’ young men. Moreover, it points to the students’ previous school experiences in “the public school system [where] they never really saw themselves as great participants or embraced the identity of being a learner.” On occasion, school is referred to as something that “girls” do, and it is for this reason that some administrators claim it is necessary to separate the boys from female students -- to give them a space where they do not have to “compete” or feel the need to show off as “men” who are “too cool for school.” The vice principal at North Star mentioned that the desire to learn “hasn’t been instilled in them.” In describing the key challenges of boys of color, he explains,

The Challenges of a New Identity Additionally, the boys in these single-sex schools face “the acting white stigma ... if [they’re] trying to achieve too much or if [they] talk a certain way.” Related, a key administrator stated that taking on a new identity is a challenge in and of itself that the boys must contend with; that is, there is a “[fear] of breaking certain stereotypes and identity that they’ve embraced and become comfortable [with].” Administrators across all schools noted that poverty and home/family life posed significant challenges that their young men face. Stated broadly by the assistant principal of Salem School, “The life outside this [school] building” is a challenge the young men must contend with -- a challenge that is heightened in the absence of a secure sense of self. By providing students with a secure sense of self, the schools essentially argue that they are able to remedy the stigma associated with becoming an educated Black or Latino male. This is viewed as a necessary component of single-sex education, given the psychological issues plaguing Boys of Color. At Washington School, the principal reported that he believes that the greatest challenges his students face are psychological. As he explained in a formal interview,

The principal mentioned his concerns around how young children can be such “psychic pincushions” -- absorbing so much around them. He makes the connection between “parents monopolizing the kids, so that these kids are like princes and they’re not used to doing anything other than having their mother around carrying their stuff for them.” He sees this type of parenting as filling the boys with unrealistic expectations of the rest of the world. Yet, another key administrator contends,

Each of the single-sex schools in this study sees itself as contending with outside forces that are preventing Black and Latino male students from accomplishing their goals, as determined by the adults who educate them. Though the schools note that the needs of this population are structural, involving a lack of quality of education, the majority of the educators interviewed attributed the majority of the boys’ social/emotional needs to cultural factors that have prevented them from achieving in school. The importance of the school is to establish “brotherhood” among their students to instill the resilience to develop and sustain their emerging academic identities. Many of the schools drew their models from the Black fraternities that many belonged to when they were university students, stressing the need to look out for each other as one another’s “keepers” or to view themselves as part of a “family.” The purpose of this school collectivity is to establish a safe space through which students may “be themselves,” even if those selves are not accepted outside the school doors. All of the schools spoke of the importance of these peer networks as a way to protect themselves and persist forward towards their goals. Acknowledging these various structural and cultural dynamics in the lives of boys of color is a complex endeavor and, according to school leaders, requires the staff at these schools to also have a deep understanding of the challenges facing their young men. At Thomas Jefferson, for example, one administrator clearly stated the importance of understanding these various factors and their influences, and their role as a school in remedying the effects of this reality while preparing the academic futures of these students:

Developing Future Leaders Developing coping mechanisms to deal with the myriad of psychological challenges, structural racism, external (community, cultural, societal, and/or familial) pressures, lack of male role models, and negative perceptions of education the young men face, however, is not enough. The schools universally expressed it was through this identity work that they could begin the work of transforming Black and Latino boys into “leaders.” Indicative of the principals across the five schools, the principal at Westward, for example, was explicit in his goal to “develop urban leaders, specifically.” He continued:

By infusing their school philosophies with ideals of “leadership” or “excellence,” these single-sex schools transmit the message that their Black and Latino male students should become examples in their own right and find ways to “give back” to their communities. The young men are being primed to lead the next generation in transformational change for their communities. Rather than sit back and be influenced by the negativity of street culture, the schools direct their students to take positive control of their own lives and take what they learn back to “the community.” To show gratitude for the opportunities they have been given, the young men are often expected to go out into “the world” and help others. The result of an education within several of these single-sex schools, in other words, is a Black or Latino masculinity defined by the ability to effect “change” for the greater societal good. In sum, the educators within these single-sex schools reported seeing themselves as essentially preparing the young men for worlds the educators perceive as being vastly different from the ones in which they currently live. This work is seen as a necessary component to “saving” Black and Latino boys from themselves and their surrounding environments, including racist institutions. If action is taken, in this case via education, the schools suggest that Black and Latino males in urban areas will view their own futures more optimistically and, eventually, become successful men who pass their success forward to their future families and communities. Academic Needs of Black and Latino Male Students In addition to articulating the social and emotional needs of Black and Latino boys, the schools in our study spoke specifically about what they perceived as the academic needs of their students. Each of the school principals framed their discussion with the alarming statistics on Black and Latino boys’ academic outcomes and their related life opportunities. For instance, Thomas Jefferson was created in response to the achievement statistics around the academic success rates of Black young men. According to the leadership of the school, Thomas Jefferson is responding to the dismal college graduation rate for Black males:

The administrators of these single-sex schools consider a lack of a college education one roadblock to “greater success.” By referencing the 2.5% of African American male public school students who will earn college degrees, Thomas Jefferson’s principal points implicitly to the structural inequities that contribute to the achievement gap. Attending a traditional public school, according to this statistic, lowers a Black male’s chances of receiving the education he needs to achieve “a better standard of living.” In order to level the playing field, all of the schools share the sentiment that it is vital to provide boys of color with “un-road-blocked access to [educational] opportunity”, and this statement indirectly implies that single-sex schooling can unblock this road. Addressing Gaps in Skills Across the schools, educators expressed that many of the students, even those considered by schools as being exceptional students, have major gaps in their educations due to their experiences in public schools. Before students can excel, they need to make up for missing skills, especially in terms of literacy, math, and critical thinking. To address these needs, the administrators generally express traditional notions of remediation as the best way to address these gaps. In order to provide boys with a “rigorous” or “challenging” education that will help them succeed ultimately, the narrative generally suggested that the schools must first teach boys the “basics” or fill in necessary skills that students are lacking. One of the reasons for these gaps, many educators shared, was rooted in the differences between how they perceived males as learning differently than females, implying that in the public schools the boys were being taught were more conducive to the ways girls learn. For example, the boys were often described as having lower attention spans than girls and being more physically actively. As such, administrators noted the need for “more hands-on kinds of programs and projects” to suit these “boy” needs. In addition to “hands-on” work, administrators often stressed the need to address “multiple learning styles” or provide “differentiated instruction” so that each of their students would benefit from their new school environments. The general conditions in traditional public schools were discussed as inadequate, unchallenging, non-rigorous, and as promoting mediocre learning, whereas the single-sex schools in this study aim to provide an equitable alternative for Black and Latino boys. The principal of Thomas Jefferson makes this point:

Preparing for College In order for Black and Latino male students to be prepared and on equal footing when they are in college, each of these schools reported that they were intentionally building and implementing a college preparatory curriculum premised on what they see as necessary, based on their own experiences in often elite colleges. For example, the principal of Westward School described framing the college preparatory curriculum on his college experience at a prestigious private university:

But exposure of these skills and content is not enough. Like many of the other administrators we interviewed, this principal also mentioned providing an additional leg-up in their students’ preparation for college. As he continued:

Raising Expectations Although these schools spoke of the specific academic needs of these students and where the leadership desired for them to go, these academic needs were also framed by an understanding of some of the structural impediments facing racial/ethnic minority communities, particularly how these impediments have impacted the Black and Latino boys they are serving. For instance, a key administrator at Thomas Jefferson suggested that the structural issue of racism prevents Black students, in particular, from making educational gains:

While this administrator’s comment is linked to the “social issues” facing Black males, one of the most common structural issues their students would have to contend with are others’ “low expectations” of them. Each of the schools mentioned low expectations as being a significant factor in the achievement gap. Boys of color are commonly seen as unable to perform in public schools and are, therefore, not given opportunities to do the type of work that will make them competitive with other college-bound students their age. The single-sex schools in this study view themselves as “raising the bar” or creating a “culture of excellence” so that the boys are fully cognizant of the high expectations they will be held to. These expectations often manifest in strict discipline policies, such as dress codes, uniforms, or “punishment rooms” for students who do not comply with school norms. Their discussion about the importance of expectation is also exemplified in a story shared by the administrator of Thomas Jefferson School, in which they were seeking funds from a private foundation: I remember one time when I was doing -- a couple people here probably know this story -- I was doing some fundraising for another school, um, and it was an all-Black, all-male high school. And I went down to talk to a donor, a fairly large foundation that had recently made a fairly large contribution to a predominantly white, affluent school. Um, so I was down there talking to them, you know, why don’t you give us some money. Um, you now, this guy said to me -- point blank -- this is the head of the foundation, he said to me, “Well, what we don’t really understand is why it’s so important for these guys to go to college. I mean, maybe you should do some type of technical/vocational focus because it’s important that we have people who deliver the mail and drive the busses ...” And he just kind of went through this long list of blue-collar jobs. And, you know, I said to him -- and I’ll tell you first we didn’t get any money from them -- [laugh]. But my response to him at that point was, did you as Somers [pseudonym] to implement a program like that before you gave them that million dollars? “Oh, well, Somers is different.” Yes, I know it is, it’s very different; I went to Somers. And I think that these guys should have the same type of experience that those guys get. I mean, I don’t think that anyone of us would say that every person in the world needs to go to college. But I think all of us would agree that enough Black men aren’t going to college. And so there’s no harm in us saying all of our graduates are going to college. Because there are plenty other places out there that aren’t sending any. So if we sent all of ours then, you know, it’s fine. Making Curriculum and Instruction Relevant The role that teachers play in their students’ development has been the source of several recent studies. Existing research suggests that not only do students need teachers who are highly skilled, but they also need culturally sensitive and responsive teachers (Ladson-Billings, 1997). Teachers are seen as a vital element to the success of the single-sex schools in this study. The need for on-going professional development is crucial for both the success of teachers and the Black and Latino male students they serve. The schools in this study described the role of teachers as centered on following the curriculum in alignment with the missions of the schools. However, some of the professional development needs of teachers have implications as to how exact the alignment can be. School administrators note teachers needing to understand what it means to provide culturally relevant instruction. It was also noted that teachers need to have a clear understanding of the research on Black and Latino boys, but administrators had offered few sources from which their teachers could draw. A large reason for that is the dearth of literature surrounding effective programs for Black and Latino male students, or for boys in general, in single-sex schools. Overall, the schools expressed the need to center teaching and the curriculum around the educational needs of their students, with careful attention given to the social, emotional, and academic challenges the boys face. These single-sex school administrators overwhelmingly reported that the curriculum needed to extend beyond the walls of the classroom in order to not only prepare the boys for academic success in these schools, but throughout the rest of their academic careers. Most of the administrators maintained that the curriculum needs to connect to the lives of their students in positive and constructive ways. Although many administrators have clear plans as to how to implement this in their particular single-sex schools, others mentioned this vaguely as something that should be done but did not have a clear plan as to how it would be put into practice. Across all schools, “relevant” instruction emerged as another key salient academic need of Black and Latino boys. Relevant instruction, defined as instruction that connects to students’ cultures or current lives, was conceptualized as a remedy for the deficits in Black and Latino males’ education, which administrators stated were caused in large part by the boys’ disinterest or their inabilities to “see themselves” in curricula in traditional public schools. As one administrator at Thomas Jefferson commented:

The education the boys receive, according to Thomas Jefferson’s vice principal, should “connect” to each “student’s life, their world, their existence” in order that it be meaningful. According to these administrators, the students in their single-sex schools need to know that what they are learning connects directly to “their world.” When asked to speak more specifically about this connection, the administrator at Thomas Jefferson said that it could be “along any lines pertaining to their identity, socio-economically, racially, gender, or just within their particular interests.” If students sense the applicability of the material they are learning -- its connection to their current experiences or their “interests” -- he argues, they are more likely to be invested in their learning. Consequently, the potential “for learning” will increase. Inherent in this statement is the belief that this particular population of students -- African American males, especially -- has had a limited ability to feel “connected” to the subject matter in more traditional educational settings, most likely because the material found in these traditional settings is (racially or gender) biased or non-conducive to the boys’ learning processes. The need for relevance in the instruction and curriculum also emerged in discussions regarding professional development needs of school staff. Although many of these schools were intentional in hiring diverse and knowledgeable staff, many mentioned there was a gap in the depth of that knowledge among their staff. At Salem, the principal discussed the pertinent need for this cultural competency among his staff:

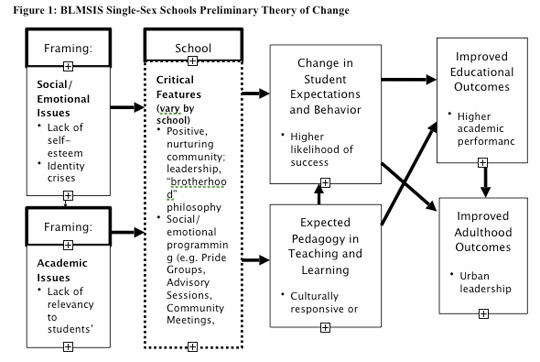

Similarly, the principal of North Star points to the importance of instructional methods and working towards “student-centered learning”: “Right now our lessons are still very teacher-dominated and we would like to move more away from that.” In addition, he notes that his school “need[s] classroom management professional development for some of [its] inexperienced teachers.” The ability to connect instruction to the students’ lives is a theme that arises throughout the interviews. At a very basic level, the program director calls attention to the importance of “cultural proficiency”, helping teachers develop “an appreciation and understanding for the culture and history of the students that they serve.” As part of this cultural understanding, he continues, “[E]very teacher in this environment, in order to be successful, has to be prepared to have some conversations around…gangs, youth culture, home life…and integrating their instruction [with] some of the concepts”, which requires that they understand and know how to “navigate some of the worlds that [the boys] have to navigate.” In sum, each of the administrators stressed the importance of tapping into either the boys’ own cultures or, more generally, “diverse” material that represents a wide range of cultural backgrounds. Doing so is presumed to ameliorate past inequities caused by the students’ inabilities to “see themselves” in what they have been taught. More specifically, the intervention theory these schools outline is premised on beliefs of social/emotional and academic needs of this Black and Latino male population. This emerging intervention theory posits various theoretical frameworks from which to examine the impact of these schools (see figure 1). Overall, our investigation of the schools has elicited multiple theories as to why single-sex schooling is a viable intervention model for the educational dilemma facing “urban” Black and Latino boys, or Boys of Color. Each of the schools in this study consists of a dynamic set of leaders who maintain that creating a nurturing school climate will positively impact the boys’ social, emotional, and academic development. While each of the single-sex schools in this study is distinct in its own right, it is framed by a set of interpretations grounded in the experiences and beliefs of the schools’ creators around what Black and Latino students need, the challenges they are faced with, and how best to address those challenges. Each of the schools in this study was constructed to serve students with “high needs” who are viewed to benefit from the opportunity to be educated in a setting designed exclusively for them. In framing their single-sex schools, the leadership and administrators sort the needs of Black and Latino male students into two main categories: social/emotional needs and academic needs, with particular emphasis on the former. The social/emotional needs of the boys are seen as stemming from a lack of self-esteem, identity crises, negative external pressures (e.g. community, familial, peer, pop cultural), lack of parent involvement or male role models, and negative views of education. These identified needs support cultural explanations for the deficits in Black and Latino males’ educational attainment levels, as responses to structural barriers. These barriers include racism, low expectations, lack of relevant instruction, and monolithic instruction techniques that do not address the boys’ learning styles. The Theories of Change framing the design for each of the single-sex schools in this study tie directly to these perceived needs of Black and Latino male students. These structural challenges are seen as manifesting themselves psychologically in the young men they serve, expressing themselves in the emotional and academic needs of the boys. As such, in order for the young men to succeed, their interventions are primarily directed towards creating nurturing environments that provide alternative messages to what they have received in traditional public schools. The interventions shared by the school administrators include college preparatory and “rigorous” curricula, “relevant” curricula, brotherhood philosophies and community service, and preparing teachers to work with this particular population of students. The data collected through the interviews and focus groups with administrators and faculty across the five schools point to a shared vision on the part of the leadership around the necessity for building a positive school climate that fosters supportive relationships among and across students, teachers, and administrators. The principals all stressed the importance of these types of nurturing relationships in promoting the achievement of the boys they serve. One of the key factors that was stressed by several of the administrators as being pivotal to their school’s success is the “buy in” in terms of the school’s mission by both students and staff. The interviews revealed that students who are not successful do not relate to, and in some cases even reject, the message that administrators and teachers convey to counter the negative images and beliefs regarding Black and Latino males that are widely held in society and within the communities the students live. The negative pull of the community context was highlighted across all five schools as a major challenge the boys have to learn how to mitigate. One of the principals especially emphasized the psychological toll exacted on poor boys of color in their neighborhoods and even at times in their own homes -- at the hands of well-meaning families with middle-class aspirations. It should be noted that all of the principals expressed the desire to build relationships within the communities in which the schools are located and saw the value of community service in the lives of their students. In terms of curriculum and instruction, all of the schools stressed the importance of knowing the lived experience of the boys they are serving. This knowledge allows them to, as previously mentioned, build and sustain positive relationships with students. The leadership at each school stressed the important of the role teachers play in instilling the school’s mission and values in their interactions with students both inside and outside of the classroom. All of the principals discussed the dearth of positive male role models for their students, and they emphasized the importance for teachers who are members of their faculty to readily embrace this role for their students. While many of the schools have teachers on staff with less than five years of experience, most of the administrators have extensive experience in schools and readily embrace the responsibility for mentoring their teaching staff. All of the principals emphasized the need for on-going professional development opportunities for their staff in order to be prepared to meet the academic needs of the population of Black and Latino boys they serve. |

|

Also see: |

| Published in In Motion Magazine October 31, 2009 |

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World || OneWorld / US || NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2012 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |