Children First and It’s Impact on

Latino Students in New York City

by Luz Yadira Herrera, CUNY Graduate Center

Pedro Noguera, , New York University

New York, New York

|

|

| During the last decade, New York City’s educational landscape has undergone a dramatic transformation. The election of Michael Bloomberg as mayor of New York in 2002 resulted in the abolishment of the Board of Education, and with the approval of the State Legislature, the Mayor assumed control over the public schools. In placing himself at the head of the largest educational system in the country, Mayor Bloomberg, a billionaire information/media executive, claimed that he would employ a business model to turnaround the failing schooling system. His business-model approach to education centered on using high stakes testing to insure accountability, decentralizing the administrative apparatus to increase school autonomy, support for the proliferation of charter schools and closing those schools deemed to be failing.

In this chapter, we begin by briefly describing the major reforms that have been implemented during the Bloomberg era. We follow this with an analysis of how Latino students have been affected by these policies. In presenting this analysis we draw upon data compiled by a variety of organizations, including the NYC Department of Education, the Parthenon Study on secondary schools, and the NYC Charter School Center, to show how Latino students have fared in New York City under Mayor Bloomberg’s reforms.

Mayor Bloomberg Takes Control: The Launch of Children First

Shortly after his election, Mayor Bloomberg appointed for US Attorney Joel Klein to serve as Chancellor for NYC public schools. Together, they unveiled the Children First reforms that launched a massive reorganization of NYC public schools. The reform eliminated community school boards, and established the Panel for Educational Policy (PEP) that took on the oversight of the City’s schools. The majority of the board members were appointed by Mayor Bloomberg, and early into his first term he demonstrated that PEP board members would follow his lead or they would be replaced. In addition, to further the goal of de-centralization, the Department of Education began to gradually dismantle the vast academic support system that previously assisted schools in the area of curriculum and professional development.

With central supports no longer available from the DOE or local school districts, schools were directed to purchase support services from newly created School Support Organizations (SSOs) or to become part of the “Autonomous Zone,” later renamed the “Empowerment Zone,”. The goal was to provide principals with more autonomy in the operation of their schools. In exchange for greater autonomy, principals were expected to meet specific performance standards (O’Day, Bitter & Talbert, 2011). The organizational changes were designed to transform NYC public schools into a competitive market for support services (Fruchter, N. & McAlister, S., 2008).

Assessment and accountability became the center of the Children First reform strategy. The reforms revamped the instructional structures in schools, established a common literacy and mathematics curriculum, required that every school have a literacy coach and a math coach, and provided schools with additional classroom materials. The reforms also established a parent coordinator in every school and placed greater emphasis on school security, designating several chronically unsafe secondary schools as “impact schools” where additional security personnel were deployed (Beam, Madar & Phenix, 2008). In an effort to increase transparency and accountability, school progress reports were released annually to the public, and letter grades were assigned to schools based on how well the school performed in comparison to schools with similar demographics. The reforms relied heavily upon state assessments, particularly the state English Language Arts exam (ELA) and State Mathematics exam for grades 3-8 and the Regents exams for grades 9-12, to measure and monitor the performance of schools. To insure that schools had access to student-level data, the DOE developed the Achievement Reporting and Innovation System (ARIS), an interactive online data tool that allows access to all stakeholders, including parents, to NYC DOE assessment data. Like several of the other measures that were implemented, ARIS was intended to significantly increase transparency and accountability system-wide.

Finally, Mayor Bloomberg and the DOE were committed to expanding school choice and creating a market place that would force schools to compete for students. To accomplish this goal, the DOE, the New York State Education Department (NY SED) and the State University of New York (SUNY) Board of Trustees were authorized to create several new charter schools. These schools received public funding and had access to public school facilities but were managed by private organizations, some of which had strong ties to hedge funds and Wall Street investment firms. Since 2002, the number of charter schools created has risen dramatically; the NYC Charter School Center (2012) reports that there are 136 charter schools currently in New York City. Additionally, approximately one hundred and forty (140) traditional public schools have been closed for failing to meet the DOE’s performance standards (Working Group Report 2012).

Assessing the Impact of Children First on Latino Students

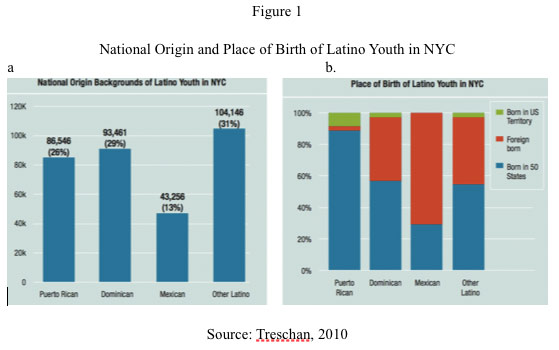

Since 2000, Latino students in New York City have constituted the largest demographic subgroup in the City’s schools (NYC Department of City Planning 2003). They are also the fastest growing segment of the school-age population. It should be noted that the Latino student population is extremely diverse, consisting of representatives from every country and territory in Latin America, as well as a large number of US-born students. Dominicans, closely followed by Puerto Ricans, constitute the majority of the Latino youth in NYC (Figure 1a). What is more, the majority of Latino youth in NYC are US-born (Figure 1b).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

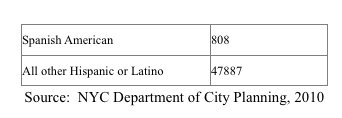

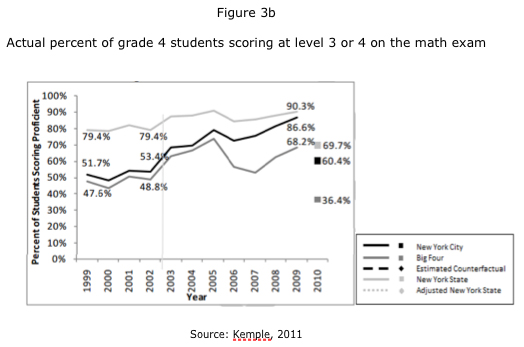

| As the demographic group with the youngest population in the City (according to the 2010 US Census, 30% of Latinos in New York are under the age of 18), Latinos have vested interest in the performance of the City’s schools. In the first few years after the enactment of Children First, NYC obtained what seemed to be overwhelmingly positive results. This was true with respect to notably higher test scores and graduation rates. Some skeptics have argued that some of the upward trends were actually the result of efforts already underway before Children First took effect (Kemple, 2011; Fruchter, N. & McAlister, S., 2008). Figures 3a and b show the percentage of students scoring at or above grade level on the ELA and math exams. It shows that there was in fact an upward trend in performance a few years before Bloomberg took office, but it also clearly shows a more rapid increase in performance after the enactment of Children First. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

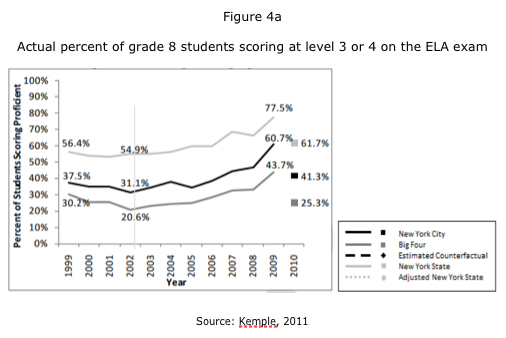

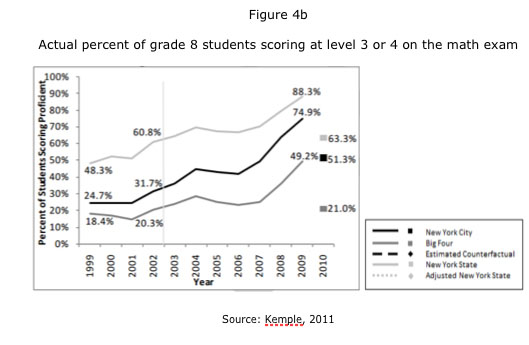

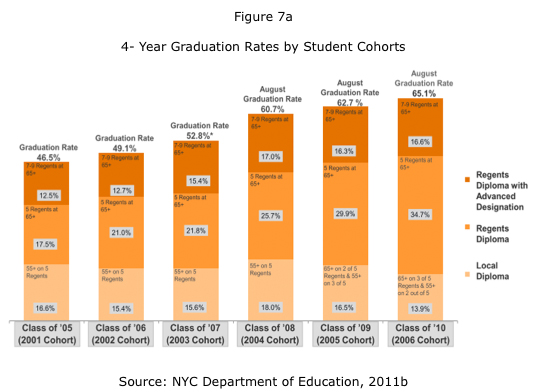

James Kemple, the Director of the newly created Research Alliance, suggests that findings from his 2011 study show that New York City was making significant progress in closing the gap in achievement between New York City and New York State. Figures 4a and b show a similar trend in 8th grade students. However, the vast majority of the credit and the praise for the apparent success being achieved in New York’s public schools went to Mayor Bloomberg and his Chancellor Joel Klein. In 2007, the City was awarded the heralded Broad Prize and designated the best urban school district in the United States (The Broad Prize for Urban Education, 2007), and Mayor Bloomberg used the progress achieved in public schools as a central tenet of his campaign for an unprecedented third term as Mayor. (Footnote 1)

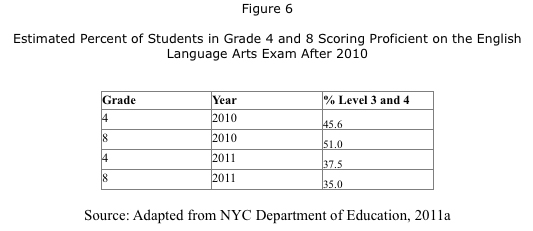

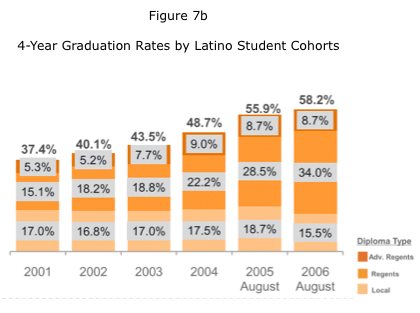

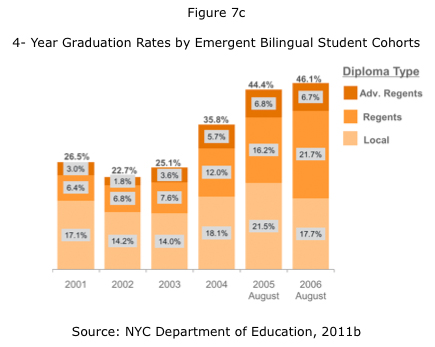

Unfortunately, the progress NY City schools seemed to be making came to an abrupt and sudden end in 2009. The New York State Board of Regents were compelled to acknowledge that student scores on fourth- and eighth-grade English language arts and math tests had been inflated and recalibrated them downward. The action effectively negated most of the test score gains that had been recorded during the Bloomberg years of control. By 2010 the Regents reported that very few of the city’s high school graduates – only 13 percent of Black and Latino students who had entered ninth grade four years earlier – were prepared to succeed in college.

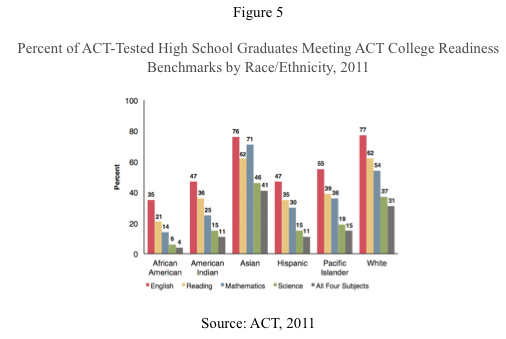

In some respects, the news was hardly surprising because two years earlier CUNY (City University of New York) had reported that more than 50 percent of the city’s public school graduates at four-year colleges, and nearly 80 percent at community colleges, were required to take remedial courses after enrolling (Smith Jaggars & Hodara, 2011). In its 2011 Condition of College and Career Readiness report, ACT (2011) showed Latino students among the least college-prepared in the nation, with only 11 percent meeting college readiness benchmarks in four core subjects (see Figure 5). Moreover, despite the bold assertions by Mayor Bloomberg and the DOE, since 2003, there had been no significant reduction in the achievement gap separating New York City’s African American and Latino students from White students on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) testing program.

|

|

|

In Grade 8 Mathematics, NAEP found that 51% of the city’s Black students scored at the lowest level (Below Basic), as did 50% of the city’s Latino students, while just 11% of Asian and 16% of White, non-Hispanic students were in that group. Placing the New York State assessments side by side with NAEP revealed that substantial “grade inflation” had occurred under Mayor Bloomberg’s leadership. In contrast to the sunny reports issued by the DOE prior to Mayor Bloomberg’s campaign for a third term, New York State found that only 2% of Black and Latino students scored at the highest level.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| For Latino students, the re-calibration of test scores proved to be devastating. Whereas 5% of the city’s students achieved the highest level of mastery, Level 4, on the Grade 8 English Language Arts assessment, when outcomes are sorted by racial/ethnic groups, 11% of Asian students are at Level 4, as are 10% of White, non-Hispanic students but just 2% of Black and 2% of Hispanic students (Schott Foundation for Public Education, 2012). In other words, it is five times more likely that a White, non-Hispanic or Asian student will have a top score on the state’s English Language Arts assessment than a Black or Latino student.

Conversely, 15% of Black and 16% of Latino students scored on Level 1 on the 2010 8th grade ELA assessments. This means it is twice as likely that a Latino student will be in this lowest scoring group than it is that an Asian student will be there, and three times more likely than a White, non-Hispanic student. Overall, 69% of the city’s Latino students are in the two lower levels of achievement on the Grade 8 English Language Arts assessment, while 60% of Asian and 59% of White, non-Hispanic students score at the two upper levels.

Why have such enormous disparities in educational outcomes persisted after ten years of reform? What the data suggest may be the underlying cause of these large gaps in performance is the link between test scores and the geographic residential boundaries of school districts. In a report entitled A Rotting Apple: Education Redlining in New York City, the Schott Foundation describes the cause of these disparities as being the result of “the corrosive impact of ‘redlining’” (Schott Foundation for Public Education 2012).

Recently, the New York City Independent Budget Office confirmed that students eligible for free and reduced-price meals, the city’s poorest children, do well in schools with relatively few poor students and students ineligible for any subsidized lunch program do not do well in schools that predominately serve students living in poverty. Sadly, only 16% of Latino students have the opportunity to attend schools where the majority of students do not qualify for free or reduced lunch. In contrast, 31% of Latino students are in schools where over 90% of students qualify for free or reduced lunch. What is more, schools that serve mostly Black and Latino students tend to attract teachers with the least years of teaching experience (Gandara & Contreras, 2010; Darling-Hammond, 2004). Gandara & Contreras (2010) found that in schools with the highest numbers of racial/ethnic minority students, a reported 88% of teachers scored in the bottom quartile for teacher quality; conversely, those schools with the lowest percentage of minorities had less than 11 percent of teachers who scored in the bottom quartile for teacher quality.

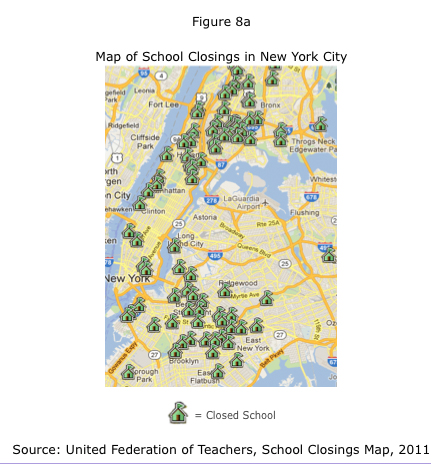

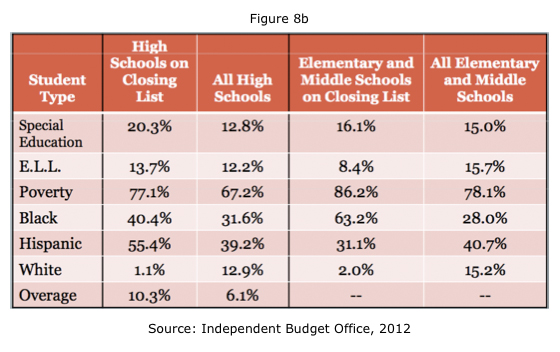

In addition to the lowered test scores and college readiness rates, the DOE’s policy of using school closure as a means to further its reform agenda has taken a particularly damaging toll on Latino students. Since Mayor Bloomberg took control of public schools, 140 schools have been closed or have been scheduled for closure (NYC Working Group on School, 2012). As the map in Figure 8a reveals, the vast majority of school closings have occurred in Harlem, Washington Heights, the south Bronx, and parts of Brooklyn, all predominantly Latino and Black communities. Furthermore, Figure 8b shows those schools closed during 2011-2012 school closings took place in those schools with a higher population of high needs students compared to the rest of the City’s schools, including special needs, poor, and Latino.

|

|

|

|

|

| A 2011 Urban Youth Collaborative study on 21 closed high schools, further reveals a pattern of outcomes that has disproportionately affected the Latino community. Similarly to Figure 8b, the study revealed that the 21 high schools that closed had higher concentrations of students eligible for free lunch (74% versus 55%) had nearly double the population of emergent bilingual students (21% versus 13%), and had a higher Latino student enrollment (47% compared to 36%) compared to the rest of NYC high schools (Urban Youth Collaborative, 2011). In addition, the dropout and discharge rates spiked during the years of the phase out in those schools, and most notably in the final year of the phase out. For instance, in the former William Taft High School in the south Bronx 70% of the students dropped out during the last year of the phase out, compared to 25% during the three years prior to closure (Urban Youth Collaborative, 2011).

In his analysis of 19 transcripts from public hearings on school closures, Kretchman (2011) provides the example of a traditionally well-performing high school whose principal disclosed that there were “‘deplorable learning conditions [in his high school during the aftermath of a nearby school closure] as a result of overcrowding,’ and argue[d] that the school was not provided any additional resources to deal with the overcrowding” (p. 17). Since many of the schools targeted for closure are predominantly in communities of color as shown above, there is a domino effect that occurs and those school that previously performed well now deteriorate due to the influx of students phased out from schools. Fruchter (2011) describes the dilemma ,

If the DOE continues to invest in structural interventions while minimizing instructional initiatives, it will exacerbate the toxic cycle that closes struggling high schools instead of improving them, and sends their students to other vulnerable high schools[,] which then become additional targets for closure. As the current list of school closings indicates, new small high schools are also becoming vulnerable to this destructive strategy of musical chairs in which the losers are always the students who most need intervention and support to succeed

(para. 10).

The Parthenon Group, a Boston-based educational consulting firm, conducted an in-depth study on NYC public schools to determine the shortfalls, provide an improvement plan, and analyze the patterns of those schools that “beat-the-odds,” that is schools that have experienced academic success despite servicing a high-need student population. The 2006 study reported two major findings, those schools experiencing higher rates of failure had two things in common: they tended to be larger in size in comparison to other schools in NYC and had higher concentrations of low-level students (The Parthenon Group, 2006). Moreover, the study found that there were almost no secondary schools in New York City serving “high need” populations that were beating the odds.

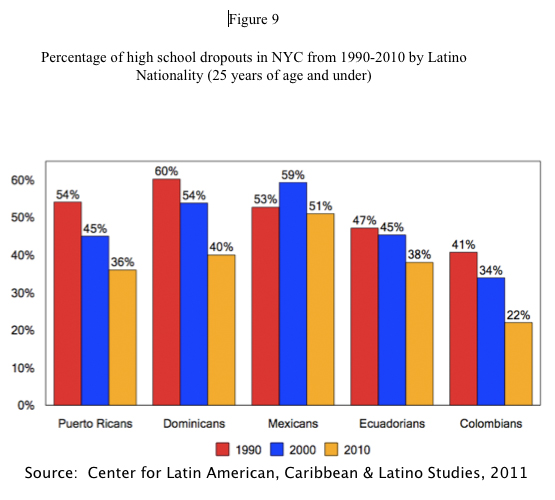

In their improvement plan, the Parthenon Group suggested a system-wide reform that ensures a more equitable high school admissions policy to prevent the concentration of low-performing students in a few schools, and the creation smaller schools that can particularly service low-level students (The Parthenon Group, 2006). Another noteworthy finding was that Latino students accounted for the largest percentage in high school dropouts for the 2004-2005 school year (The Parthenon Group, 2006). Meade, Gaytan, Fergus, & Noguera (2009a) found a similar pattern in the 2006-2007 high school cohort. Although the percentage of high school dropouts in NYC has decreased since 1990, the percentage of high school dropouts is still alarmingly high, most notably within Mexican and Dominican youth (see Figure 9). Additionally, Latinos and Black students in secondary education were also more likely than their White and Asian counterparts to be over-age and off-track on the number of credits needed to graduate (The Parthenon Group, 2006). This is cause for further concern since those students who are more likely to drop out are those students who are overage (Meade, Gaytan, Fergus, & Noguera, 2009a).

|

|

|

| The Impact of Charter Schools

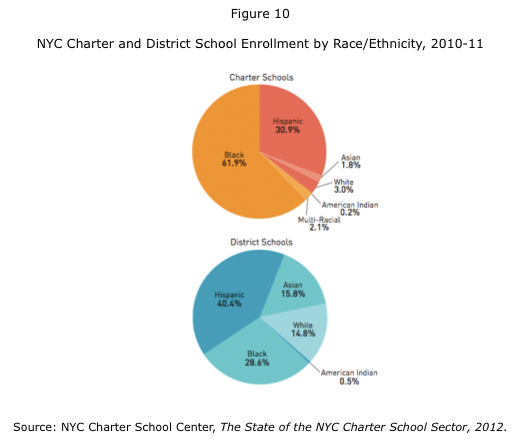

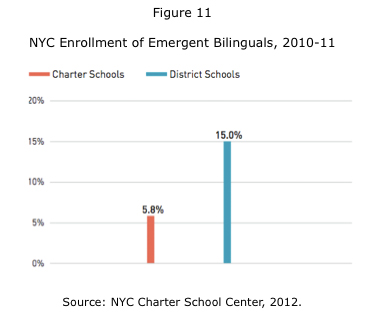

As we mentioned previously, the number of charter schools in NYC has substantially increased since the reforms Children First were implemented. Their proliferation has been largely fueled by school closures in NYC, which has created the physical space in which to launch new schools, primarily charter schools. The charter school movement has seen its share of supporters, as well as its critics. Data compiled by the NYC Charter School Center provide an insight into the composition and character of charter schools. Since Bloomberg launched Children First, charter school student enrollment has increased from under 5,000 students in 2003 to an impressive 47,000 in 2012 (NYC Charter School Center, 2012). However, charter schools have consistently been criticized for enrolling a lower percentage of Latino students, particularly recent immigrants and English Language Learners (ELLs) in comparison with neighboring district public schools. Figure 10 shows that charter schools disproportionately serve Black students; NYC charter schools have a 62% Black student enrollment, whereas district public schools account for only 28.6%. What is more, charter schools serve 10% fewer Latinos than the surrounding district public schools, 30.9% compared to 40.4%. Figure 11 shows further disparities in the enrollment in the emergent bilingual student population, another critical subgroup of students. It reveals that district public schools in 2010-2011 were nearly three times more likely than charters to enroll emergent bilingual students, 5.8% compared to 15%. According to the latest NYC DOE Demographics Report (2011), 65% of emergent bilinguals are Spanish-speaking, thus, the majority of emergent bilingual students are also Latinos.

|

|

|

|

|

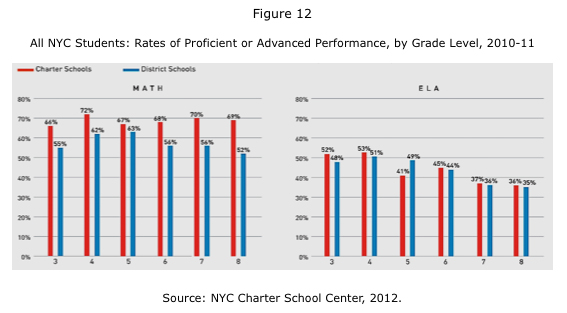

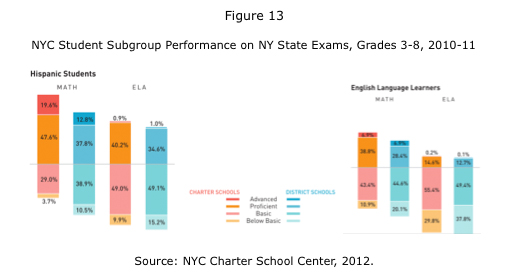

Enrollment disparities aside, charter schools have shown superior performance to district schools by some measures and no real differences in student performance by others. Figure 12 illustrates a higher percentage of students in charter schools than in district schools scoring at or above proficient levels on the 2011 New York State Math exam. On the 2011 NY State English language arts exam (ELA), students in both charter and district schools performed at comparable levels; notably, however, district school students in the 5th grade showed higher performance to that of charter school students by 8 percentage points. Nevertheless, Latino students in charter schools scored higher on both the ELA and math exams. The emergent bilingual student subgroup showed a similar trend, but to a lower extent (NYC Charter School Center, 2012). Figure 13 shows that 10% more Latino students in grades 3-8 scored at or above grade level on the Math exam in charter schools compared to district schools, and nearly 6 percentage points higher on the ELA. Moreover, Figure 13 also shows that 10% more emergent bilingual students in grades 3-8 also performed at or above grade level on the math exam in charter schools compared to district schools. In ELA, figures were similarly lower as with the Latino student subgroup, favoring charter schools only a small difference of 2 percentage points. It is important to note, however, and as previously specified, Latinos and emergent bilinguals are two underrepresented student subgroups in NYC charter schools. Suárez-Orozco and Sattin (2009) have also shown that charter schools have extremely low levels of emergent bilingual student enrollment compared to nearby school districts. Critics have argued that since charter schools do not receive the extra public funding to service emergent bilingual students, they have no incentive to serve emergent bilingual students or immigrant families (Hoxby & Murarka, 2009; Leal & Meier, 2010). Nevertheless, there are specialized charter schools that serve only emergent bilingual students and that should not go unnoticed.

|

|

|

|

|

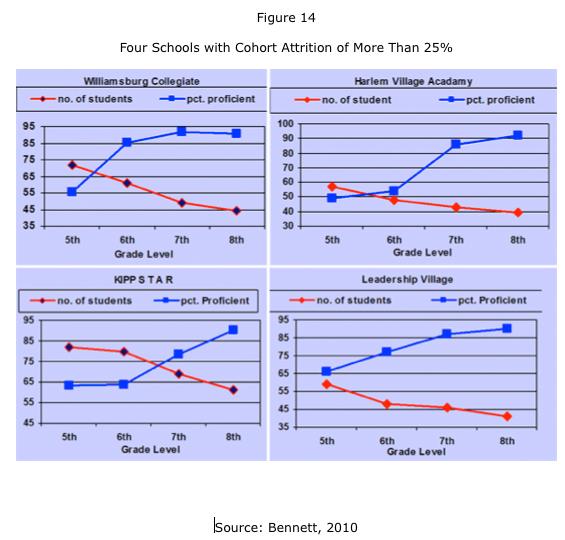

| Charter schools have been at the center of a lot of controversy due to accusations that some are counseling certain student populations out of their schools. There are also concerns that some charter schools have alarming student attrition rates. In her study, Bennett (2010) has shown a disconcerting pattern of student attrition in NYC’s highest performing charter middle schools. She found that 8 out of 13 of these had an average attrition rate of 23%, with one charter school showing a 40% attrition rate, whereas the surrounding district schools showed a steady or an increase in student enrollment (Bennett, 2010). She further notes that “as students disappear, the high-attrition schools record ever higher percentages of proficient students [in high-stakes exams]. This same pattern plays out in all 13 schools. Schools with more than 20% attrition see their percent of proficient students rise to over 90%” (Bennett, 2010, Rising Proficiency, para. 1). Put differently, some schools have figured out that one way to raise test scores is to find ways to remove students that are likely to bring them down.

Figure 14 shows a revealing pattern of increasing proficiency rates as student enrollment decreases in four NYC charters.

|

|

|

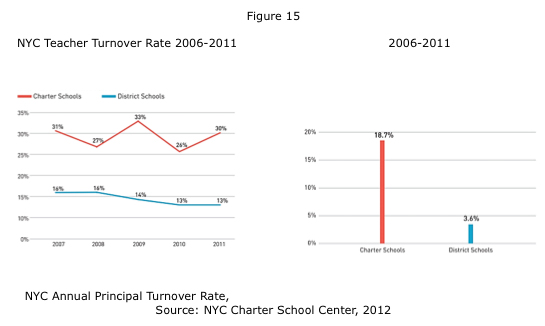

The NYC Charter School Center has also compared the turnover rates for both teachers and principals in charter and district schools. Figure 15 displays a striking difference in turnover rates; it shows that 26% to 33% of charter school teachers have left their positions every year since 2007, whereas the yearly district school teacher turnover was between 13% and 16% during the same years. What is more, charter school principals were six times more likely to leave their positions at a charter school than were district school principals, 18.7% compared to 3.6%.

|

|

|

| School closures have coincided both with the proliferation of charter schools and the increase in small schools. The Parthenon Group has cited small schools as one of the potential solutions to the problems confronting larger schools. Small schools in NYC have gained considerable support in NYC because they have out-performed larger schools. However, skeptics maintain that part of the reason for their improved performance is because they were shielded from serving large numbers of ELL and special education students during their first few years of operation, and more needs to be done to service the high-needs student populations. Michelle Fine (2005), for instance, has argued that small schools have served Latino students far better than large urban schools. In her study, students in small schools reported higher levels of satisfaction with their schooling experience; they reported significantly higher levels of feeling academically challenged and well prepared for college than their counterparts in large schools (Fine, 2005). Flores and Chu (2010) conducted a study to find how the rise of small schools has impacted Latinos in NYC and they found that small schools were more successful in keeping Latino students on track for graduation based on their accumulation of credits. Small schools also had overall higher graduation rates than larger schools (Flores & Chu, 2010). However, the authors question the quality of the programming available in the small schools; the small schools in their study were far less likely than large schools to offer bilingual programming, often only offering English as a Second Language (ESL) services to emergent bilingual students (Flores & Chu, 2010). Moreover, because of their size and limited resources, small schools are less likely to offer advanced placement courses, special education services, and the broad range of electives offered at comprehensive high schools. And as Krashen and McField (2005) have shown, high-quality bilingual programming for emergent bilingual students is superior to English-only approaches (as cited in Flores & Chu, 2010).

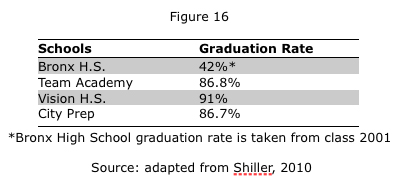

Another study on small schools presented revealed a problem with their pedagogical approach, which according to some research, has frequently centered on test preparation. Shiller’s (2010) study reveals the case of a large Bronx high school that was divided into three smaller schools, which she refers to as Team, Vision and City High Schools. She found that there was an improvement in attendance and graduation rates (See Figure 16), a finding consistent to those studies cited above; nonetheless, she also found that teachers were engaging in minimum standards and test-centered pedagogical approaches (Shiller, 2010).

|

|

|

| She found that students’ critical thinking skills were not nurtured in these schools; instead, much class time was devoted to test-prep (Shiller, 2010). Shiller (2010) goes on to note that 90% of the schools’ student population was Black or Latino.

Conclusion:

The Unfulfilled Promise of Children First for Latino Students

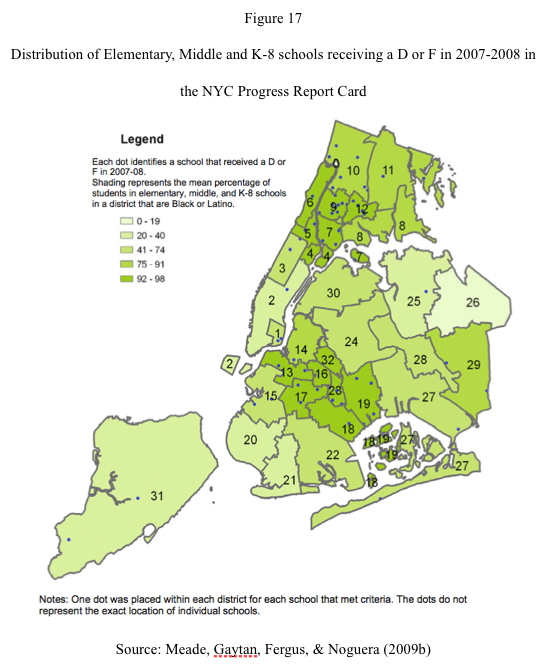

Over, sixty years after the Supreme Court’s Brown decision, New York City continues to be highly segregated. Racial isolation is especially evident in the city’s schools where Latino students are concentrated. In fact, the rate of racial/ethnic concentration in public schools is among the highest in the nation (Schott 2012). In neighborhoods such as the South Bronx, Bushwick, East New York and Washington Heights, large concentrations of high-needs Latino students continue to be served by low performing schools. A study by Meade, Gaytan, Fergus, & Noguera (2009b) found that those schools with higher concentrations of Latino and Black students were also the City’s lowest performing schools (see Figure 17). This map (figure 17) also shows the patterns of racial/ethnic concentration across the city, revealing the high levels of segregation and concentration within the Latino and Black communities.

|

|

|

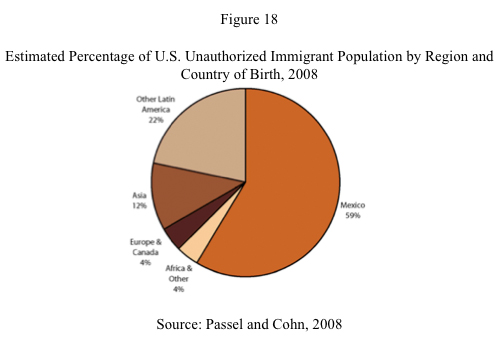

Undocumented status is another challenge facing the Latino community, further limiting higher education and employment opportunities. According Motel and Patten’s (2012) Pew Hispanic Center Report there are 40 million immigrants living in the U.S., nearly half (47%) of them Latinos. As of 2010, there was an estimated 11.2 million unauthorized immigrants living in the U.S. (Passel and Cohn, 2011). Figure 18 shows that in 2008, the estimated percentage of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. by nationality, showing that the vast majority of undocumented immigrants coming from Mexico (Passel and Cohn, 2008).

|

|

|

| On numerous occasions, Mayor Bloomberg and former Chancellor Joel Klein defended their reforms by asserting that “education is the civil rights issue of the 21st century”. They also castigated their critics as defenders of failure and the status quo. Yet, a close look at how the reforms initiated under their leadership have impacted Latino students reveals that two of the most important issues confronting Latinos, namely school segregation and the needs of undocumented students, have not even been part of their reform agenda. As Mayor Bloomberg’s third term comes ot an end and a new mayor and Chancellor assume office, it will be essential that they learn lessons from the past ten years of reform. Latino students particularly, cannot afford another period of experimentation that promises a great deal but delivers far less than is needed. |

|

|

Published in In Motion Magazine September 7, 2013.

|

|

|

|