|

Interview with Faustino Torrez of

Nicaragua’s Association of Rural Workers Part 1: The People and Their Land Managua, Nicaragua |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Faustino Torrez is a national leader of the ATC (Asociación de Trabajadores del Campo /Association of Rural Workers). The interview was conducted (and later edited) by Nic Paget-Clarke for In Motion Magazine on July 1, 2008 in Managua, Nicaragua. Translation to English by Nic Paget-Clarke and irlandesa.

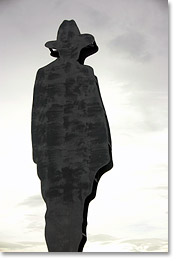

Faustino Torrez: My name is Fausto Torrez, but officially, on my passport, I am Faustino Torrez. I am responsible for international relations with the ATC. In Via Campesina, I work on what is called the Rural Campaign for Agrarian Reform. I also work on the issue of agricultural food and, now, on Via Campesina communications within Central America. Lastly, I coordinate training programs for CLOC. CLOC is the Latin American Coordination of Peasant Organizations. In Motion Magazine: Can you speak a little about your personal history? Faustino Torrez: I was born in a farming community called Monteverde in a town called San Dionisio, in Matagalpa department. I have a farmworker background. I spent the greater part of my life in this town, San Dionisio. I went to primary school there and then I went on to do religious studies. After that, I joined the Sandinista Front as a frontline soldier. When the Sandinista Front came to power, I worked in the party leadership in Matagalpa and Jinotega departments. There, the tasks assigned to me by the Sandinista government included working in areas affected by the military conflict. I found myself with men and women farmworkers. I was working to defend the revolution and training leaders for work in the countryside. Additionally, I received training in the Party School in Moscow, Russia and in the Bulgarian Science Academy. Afterwards, I became a licensed professional in business administration, which I saw as a duty for the economy. In university, I trained for a career in business. I took many postgraduate courses in rural development, political training, and communication techniques. After the Sandinista government lost the elections in 1990, I finished my schooling with the ATC, in leadership training. From there, I became the national director of education, at the National ATC School. And after that I assumed my international duties. These international duties included working directly with La Via Campesina and CLOC. I have spent many years with Via Campesina and CLOC. CLOC was very important for Latin America from 1996 to 1998. In the ATC, I was organizing the progress of technical training and as part of that I incorporated the subject of the campesino, as a result of my roots in the countryside and, even more, because I have worked with farmworker men and women. I have worked more than a little in the countryside. I used to work in coffee production and with livestock. I used to tend cattle. I used to cultivate coffee on a family farm. That is a little, in broad strokes, of my political history, though clearly there is more to tell -- but I am telling the basics. Obviously, there is more to my military political life which is important. And, yes, I spent ten years fighting against the Contras. Ten years of military struggle -- I love Sandinismo -- actually, eleven because I had joined earlier. I saw the damage of war. In Motion Magazine: What did the Contras do? Faustino Torrez: The phenomenon of the war was a very bitter story for (Central) America, and above all for Nicaragua. Especially for Nicaragua because we triumphed in 1979, and in 1980 we did our national literacy campaign. We succeeded in lowering illiteracy in Nicaragua 12.6 percent. We lowered the proportion of illiterate people in Nicaragua. We succeeded in bringing education to the countryside, and credit for the farmworkers. But at the same time as the popular Sandinista revolution was being developed -- a model for the counterrevolution was being born. This counterrevolution was fed from the outside for political reasons. The U.S. government supported this counterrevolution because it represented difficulties for the Sandinista government. Some people, peasants particularly, went over to the Contras because they didn’t have adequate education, or much political training; others because we committed some errors in the construction of the government. And yet others because they knew there was a chance to better themselves, and others because they really did feel threatened by Sandinismo. We made a revolution and in a revolution errors are made. These errors are what generated some unevenness in the countryside. For this reason, the phenomenon of the Contras was growing, and, at the same time, there was a permanent campaign of propaganda from the right, from the church -- and with international support. In Motion Magazine: Can you talk a little about these errors? Faustino Torrez: Every revolutionary process in the world has its own special characteristics. There was nothing like the Vietnam process with the ideas of Ho Chi Minh. There was nothing like the revolutionary process of the Bolshevik revolution with Lenin and Trotsky. Similarly, the liberation processes in Africa -- they weren’t the same. Cuba had its own particularities, its own characteristics. And Nicaragua had a very original revolution, very particular to Nicaraguans. At any given moment, there is no recipe or written manual which says what should be done and what should not be done. And, generally, at that time, the majority of us were very young. The majority of us were seventeen, eighteen years old -- and we had great responsibilities. On the other hand, there was a political tendency, a national direction, which also had its own difficulties. If we had a theory, it was that we identified ourselves with the free thinking of Augusto Sandino. For us, what was clear was our nationalism and anti-imperialism. This was very clear. But, the process of creating a new social structure, socialism, was very complex, very difficult. In Europe and in the world at large -- there was a society for which they were not making books or manuals. We came to power in an era when the Soviet Union was already in decline. It was not a good example because the world identified socialism with Russian socialism, with the socialism in European countries. And in the Cuban case, they have their own characteristics, such as Cuba is an island with a great leader, Fidel Castro. There were some similarities, there were some things similar to us, but there were other things which were very particular to Nicaragua. For example, when we came to power, Nicaragua had the backing of the popular church. During the seventies, the famous liberation theology was at its height in Latin America. Many Christians who were the base of the church began to see justice in this successful phenomenon. They saw Somoza’s repression as the principal enemy. This sector of the church was very important in creating a general political consensus in Nicaragua. But this sector of the church did not play the same role when we were in power. When we were in government there were other interests and some in the church left us. We did not know how to properly deal with the subject of religion. In Nicaragua there is also the very difficult subject, ethnicity. In Nicaragua, there are the indigenous communities, or original people as they are called. There are the Miskitos, the Mayagnas, the Garifunas and those from Rama Cay. There is also the Creole population, who are of African origin, on the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua. These communities demand autonomy and Sandinismo supported that, but in the beginning it was difficult. Perhaps because of the war, perhaps because there were already difficulties in the country in those years, because internal politics were complex, indigenous issues and religion were not correctly dealt with. There was also the issue of private property. In Latin American countries there exists a tendency to own private property, to own land, even if the land is not being used. The government in the ’80s had two approaches towards achieving social development in the countryside: enterprises which were designated property of the people, and cooperatives. But this development was weak because, during those years, we were fighting against the war of aggression (editor: supported by the U.S. CIA) and many men from both the state enterprises and the cooperatives were involved in the military defense of the people’s Sandinista revolution as militia -- and this made economic development difficult. So, as a result, many of these units were poorly tended to. And also, we neglected the campesino family farm economy. We didn’t see the importance of this issue of the small farmer. We were more focused on the large social enterprises, to generate income for the country. We neglected peasant production, and, in the end, some joined the ranks of the Contras while others continued with the People’s Sandinista Army. For that reason, Sandinismo lost the elections when a large part of the campesino electorate voted against the war, and, in general, the majority of the campesino vote went for the right. Ever since the Sandinista government in the ‘80s, the problem of the campesinos has not been understood. We did not know how to give correct attention to the countryside and they gradually became a social base for the counter-revolution. The family farmer economy continues to be a matter of much reflection through the years. U. S. Intervention: The Nicaragua canal In Motion Magazine: Why did the United States invade Nicaragua in the 1930s? Faustino Torrez: A little history. The first intervention in Nicaragua was a lot earlier. It was in 1840 when England and the United States decided to use Nicaragua to build a canal between the oceans. Then, in 1854, because of political conflicts in Nicaragua between the Conservative Party, in Granada, and the Liberal Party, in Leon, and a resulting lack of governability, one of the political groups hired a gringo, called William Walker, and with him Byron Cole. William Walker came to Nicaragua and declared himself president (with Byron Cole as vice president). Additionally, he imposed English as the official language and he promoted slavery. William Walker burned down Granada, now one of our most visited tourist cities. Walker came with a group of soldiers who supported the South, the Confederates and secession (in the U.S Civil War). And this group of soldiers remained in Nicaragua. The idea was to take over Nicaragua because Nicaragua had the ability to be a passage between the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans. When William Walker came to Nicaragua he became a threat to Central America. So, the Central American countries, the Nicaraguan indigenous population, and other patriotic Nicaraguans, united against Walker and defeated him in 1856. He was defeated in San Jacinto. He was defeated in Rivas. And, finally, he was expelled from Nicaragua. In 1860, he was shot (executed) in Trujillo, in Honduras. U. S. Intervention: Bananas, Gold, Silver Afterwards, came the United Fruit Company -- the age of "the Banana Republics" -- with an interest in banana production, above all. Others were interested in gold, silver and other precious metals mining. There was always the intention of emptying Nicaragua of its natural resources -- with the complicity of some Nicaraguan political leaders. In 1893, Jose Santos Zelaya became president of Nicaragua. Jose Santos Zelaya was a nationalist president who was influenced by the ideas of the French revolution. He was more influenced by Europe than by the U.S. He implemented some legal reforms in Nicaragua which had a very nationalist character. But he entered into conflicts with the U.S., so they removed him. In those years, the U.S. ambassador kept marines in various countries, ready for orders. Zelaya lost power, and then two other leaders rebelled against this first intervention, in 1910. A Nicaraguan patriot called Benjamin Zeledon died confronting the North American invasion. And Sandino, when he saw how the body of Benjamin Zeledon was treated, that contributed to creating in Sandino an anti-imperialist consciousness against the foreign intervention. There had always been political contradictions between the Liberals and the Conservatives, and in 1925, when one of the parties (the Conservatives) requested intervention from North America, the U.S. Marines. The Marines came to Nicaragua to impose order. When he saw this, Sandino took up arms with the Liberals and waged war against the Marines. But, when President Jose Maria Moncada signed a peace treaty which allowed the Marines to stay, Sandino rebelled with arms. Sandino called for national dignity and a guerilla army was born which lasted from 1929 to 1934, when he was assassinated, here in Managua. These interventions by the U.S. government were, first, for U.S. interests in Latin American natural resources. Secondly, there was little dignity in some of the political ideas in some countries. And thirdly, when there were contradictions between one and another party, the losing political party sought help from the U.S. When there were conflicts over power between the Liberal and Conservative parties, when one or the other was losing, then they sought the help of the U.S. Marines to impose order. They always wanted to resolve their problems with the support of the United States. So interventions and a foreign presence were generated here. The U.S. Marines came here many times. “I am here because this party and its leaders invited me to impose order.” This opportunism and appeasement permitted the intervention of the U.S. government. That was one of the causes, but there are many reasons. Yes, these countries are very small and never have had true independence. But also there were anti-patriotic attitudes. That is why, afterwards, we lived under the Somoza dictatorship, why Somoza the dictator governed with the complicity of the United States government. United Fruit and the Green Revolution In Motion Magazine: Was there a Green Revolution here, or just United Fruit? Faustino Torrez: Both. First, United Fruit Company worked in two assigned areas where they were able to do banana production. But also, the Green Revolution had its impact -- more ecological than political -- from the ’50s on, with the development of the boom in cotton production. The arrival here of the cotton-producing transnationals, the production of chemical fertilizers, and the appropriation of areas of land for the cultivation of cotton generated the mono-cultivation of cotton. That brought on an ecological disaster. At the same time, though, it created a working class. It was bad and it was good at the same time because it generated class consciousness, a working class which had a more progressive position -- at least, years later, for the children of those workers. But it wasn’t just that they created an ecological disaster here. It was that the worst of the contamination was on the best lands of Nicaragua -- in Chinandega and Leon. The water and the soil are contaminated and this, along with the deforestation, has upset the equilibrium of Nicaragua’s environment. You have to remember that Nicaragua is very vulnerable to natural disasters, it is very vulnerable to ecology-equilibrium problems: hurricanes, earthquakes, tidal waves. All these have been problems for Nicaragua. Additionally, there are those who, not necessarily politicians, were influenced by the interest in exploitation by the transnational corporations, who continued with crop cultivation, here in Nicaragua, without paying attention to what had happened before, for example in banana cultivation, with the use of Nemagon, which is a very bad chemical. Here in Nicaragua and in Latin America there are many toxic chemicals which have been banned from use in cultivation (in other countries), which have caused problems for the human body and also the environment, but are used here with impunity. In Motion Magazine: During the Green Revolution, did people move to the cities? Faustino Torrez: Yes. During this period, people migrated from the countryside to the city. But it was not so much because there was no work in the countryside. Nicaragua is a small country, with barely six million inhabitants. At the time of the Green Revolution, Nicaragua had two million inhabitants at most. The population of workers focused on cotton production when there was cotton; and after that coffee, when there was work with coffee production; and then bananas. There were three industries using manual labor -- cotton, coffee, and bananas. So, the manual labor was mobilized seasonally, according to the time of the year, to cultivate bananas, coffee, and cotton. Another sector of the population focused on trade. The people who were not mobilized to cultivate coffee, or cotton, or bananas, or trade focused on small-scale production, peasant farming. In Motion Magazine: What happened in the ’80s during agrarian reform? Faustino Torrez: In Latin America there have been various radical agrarian reforms. There were radical reforms by popular governments -- such as that in Bolivia, or that of Velasco Alvarado in Peru. In Mexico, Lazaro Cardenas (president of México, 1934-1940) made agrarian reform, as did the Zapata revolution was for agrarian reform. After that there was Cuba with the Cuban revolution. And in Nicaragua, when we came to power, the first thing we did was to announce agrarian reform, to make a real law. We implemented a process of agrarian reform for campesino families, through the municipalities, which was appreciated and which helped to develop good feelings from the communities to the Caribbean areas. It also had a good effect on the guerrilla fighters. When we arrived, the old power was blood-stained. We carried out a profound agrarian social reform which limited how much land could be held and also gave land to those without land. Our agrarian reform did all of this. We gave land to the peasants, as well as technical assistance. We improved the roads to increase production. We distributed technical, financial and banking assistance to the peasants. From 1980 to 1984, we shared land, credit, technical assistance, technological education of all types -- and roads. We continued until the elections stopped us. But agrarian reform was not the only thing seen as a benefit to the countryside during this period. Health care. In mattes of healthcare, Sandinismo provided the best health care the country had had. In the ’80s: healthcare was free, education was free. Also, many peasant students went away to study in Bulgaria, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Russia, Cuba, and East Germany. Many went to the countryside as doctors. So, medicine, education, and culture were all advanced in those years in Nicaragua. This is recognized by all the world -- by many critics and non-critics. With agrarian reform we delivered more than 10 million hectares of land to the peasants. And all of these benefits were signs of the revolutionary process, of Sandinismo. Obviously, there were errors also as I spoke of earlier, but if we sum up the errors and the benefits, there were more benefits than errors. There was a lot of support given to the countryside. Sandinismo brought light to the countryside for the first time in the history of Nicaragua -- benefits to the countryside. Social benefits which also brought regulations to rural labor. The agricultural laborer used to work twelve hours a day. Labor regulations were enacted so that there would be no exploitation. So, agrarian reform, education, healthcare, culture, social benefits, they were a hallmark of what Sandinismo introduced to Nicaragua in this era. In Motion Magazine: What is happening with agrarian reform now? Faustino Torrez: Agrarian reform always has to be appropriate for the moment. In Nicaragua, there is a root problem with the issue of agrarian reform. It is very difficult, very complex. Complex because during the agrarian reform in the ’80s we gave land to thousands and thousands of peasant families, and we wanted worker enterprises and cooperatives, but when the Sandinista Front lost the elections in the ’90s, many business owners returned to reclaim their lands. First, Sandinismo never thought it was going to lose the elections. And then, much of the land which we gave to the campesinos, we did not give them legal documents. We gave them documents of deed, not of right -- they were not legal documents. So, now a peasant who has a title from the agrarian reform does not have a registered document for that property. This situation created confusion. Secondly, the peasant who received collective land wanted to develop the land as an individual, not collectively. The concept of collectivity, the collectivity of the community had not come to be yet -- in the ’80s. The general attitude was a little individualistic. When the ’90s arrived, different people had been listed on many of the titles which we had given out to the people and this generated confusion on the subject of property. Also, other peasants, who did not have credit because Sandinismo lost the elections, sold their land. The agrarian reform law was not in effect in those years. There was a national confusion on the subject of property. So, now in Nicaragua, speaking about property is a very delicate subject because we, the Sandinistas, confiscated lands. Was Sandinismo going to confiscate land on returning to power? The big business people made political propaganda with this -- as did some small producers. In the ’90s and in the years since 2000, the subject of land in Nicaragua has not been so much about agrarian reform, as how to deliver more land. If land is not legally owned we endeavor to legalize it. The peasants needed to legally own their land. If there are people who do not have land but there are a lot of people who have unregistered land, it is necessary to legalize it, organize it, and register it, otherwise a mafia could be set up in Nicaragua, of people ordering campesinos to take land, so they could take power. Timal, Gringo Caitudo, U.S. interests The problem is that the only way to bring order to the land question in Nicaragua is with Sandinismo. The only ones who can straighten it out, who can resolve the issue, are the Sandinistas because we were the creators of the problem -- because we did not legalize the land, and because we want to now organize the land. For example, Timal, which you visited yesterday, where part of the land was purchased and part of it was confiscated. In the ’80s, a sugar mill called July Victory was constructed there. This central sugar mill was built by the Cubans. It was constructed in Cuba, and then Fidel Castro came here and delivered it to Nicaragua. When we lost the elections, the whole infrastructure was sold, given away, was stolen, and now the land remains in legal conflict. It was a threat to the state. Now different groups have occupied the land. The neoliberal governments of (presidents) Violeta (Chamorro), (Arnoldo) Aleman, and (Enrique) Bolaños, they were not able to resolve the problem. It is now up to the Sandinista government to solve this problem, to deliver these lands to the campesinos who are in possession of them. But just like at Timal, there are other grave land problems in Nicaragua. There is what we call in Nicaragua the “Gringo Caitudo”. The “Gringo Caitudo” refers to certain Nicaraguans, some of them Somocistas, others not, who went away during the ’80s to the United States. There, in the United States, they pursued politics and the Reagan and Bush Sr., governments granted them U.S. citizenship. Then, in the ’90s, with the Violeta (Chamorro) government, they came back to Nicaragua -- but they were no longer Nicaraguans. They came with U.S. passports, and the U.S. ambassador, and the United States, they said it was in the United States’ interest to protect these large farms, these landowners. There were Nicaraguan farms and enterprises about which gringos now say, “I reclaim these lands. They are mine.” And the governments of Violeta, Alemán, and Bulaños had to return this land to these U.S. citizens. The peasants on the other hand, had it taken from them. So, that is the story of these people who are called “Gringo Caitudo”. “Caite” is an indigenous word for a shoe, here in Nicaragua. A “Gringo Caitudo” is a Nicaraguan with a political history (from the ’80s) who went to the U.S., became a North American, and now wants to reclaim his land as a gringo. Property in Nicaragua is a very complex issue and the only way to resolve it is for the government to straighten out what it left undone. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Published in In Motion Magazine December 18, 2009.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2018 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |