|

Interview of Duncan and Kath Fraser

with Fiona Mackenzie

Crofting: In This Strategic Place

Toscaig Township, Applecross Peninsula,

Ross and Cromarty, Scotland

|

|

|

Duncan and Kath Fraser (with their two children Morganna and Zebadiah) and Fiona Mackenzie. All photos by Nic Paget-Clarke.

|

|

|

|

Looking inland, down an inlet, towards Toscaig on Applecross peninsula, Ross and Cromarty, Scotland.

|

|

|

|

Young Herdwick sheep on the Fraser croft. The Frasers and Fiona Mackenzie have Herdwick, Scottish Blackface, and Cheviot sheep.

|

|

|

|

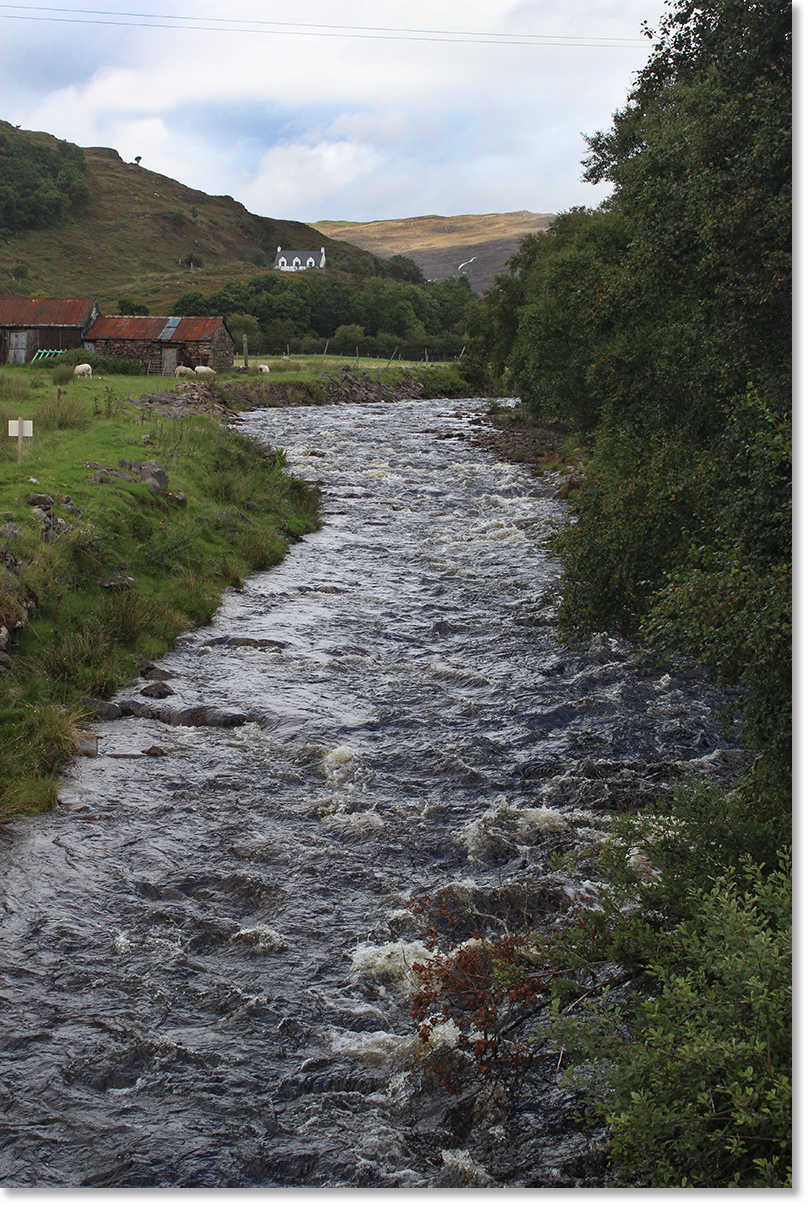

A river rushes towards the sea, the Inner Sound, between the Applecross peninsula and the Inner Hebrides islands.

|

|

|

|

Duncan Fraser.

|

|

|

|

Kath Fraser gives out a little food to gather some sheep.

|

|

|

|

Fiona Mackenzie.

|

|

|

|

Alert on the croft. Toscaig.

|

|

|

|

Morganna feeds a couple of the family's sheep.

|

|

|

|

Zebadiah gets a better view.

|

|

|

|

On the Fraser croft looking towards the sea.

|

|

|

|

Duncan and Kath, just prior to tying closed the gate to the field of sheep.

|

|

|

|

Two Cheviot sheep confer.

|

|

|

|

Heather on the moor by the northern coast of Applecross peninsula.

|

|

|

|

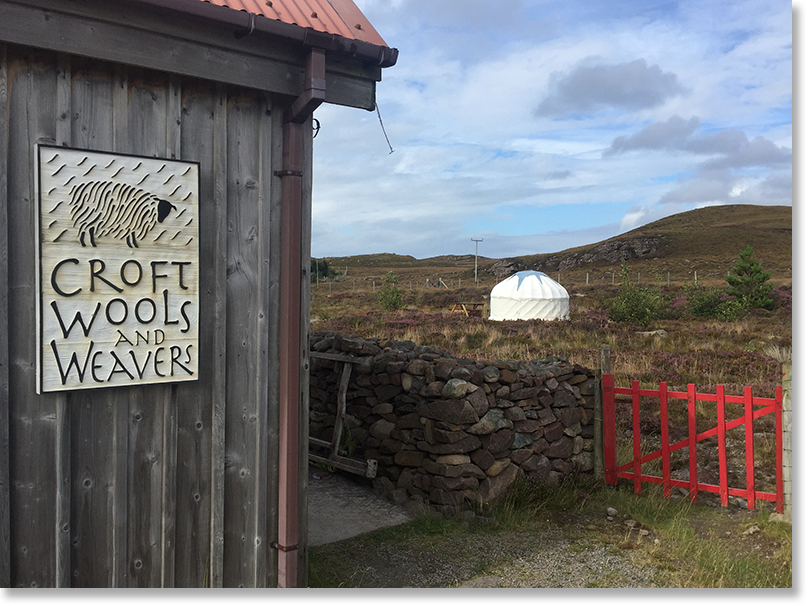

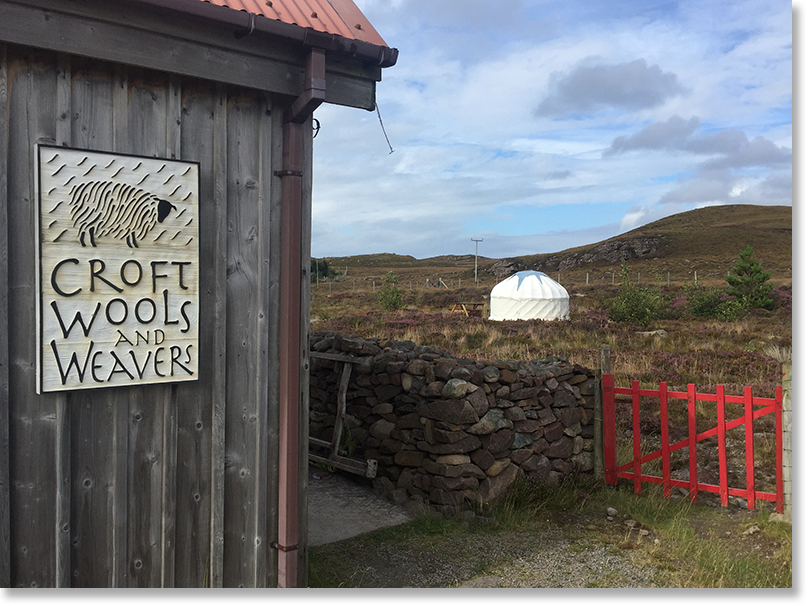

A local business, Croft Wools and Weavers. Their Wool Trailer advertises hand spinning, hand weaving, knitting wool, weaving, and knitwear. Applecross peninsula, Ross and Cromarty, Scotland.

|

|

|

|

Cut from wood, a sign for Croft Wools and Weavers.

|

|

|

Duncan and Kath Fraser (with their two young children) and Fiona Mackenzie are crofters living in the rural township of Toscaig on the coast of Applecross peninsula in Ross and Cromarty in northwest Scotland. They raise sheep and cattle on their in-by land and out on the communal grazing land. Their crofts are adjacent and Fiona Mackenzie’s home is close to the Fraser family home.

This interview was conducted (and later edited) by Nic Paget-Clarke for In Motion Magazine on September 2, 2016 in the Fraser’s home around the kitchen table.

Quick Links:

- Part 1: Using the Crofts as They Were Meant to be Used

- Part 2: Animals and Land Management

- Part 3: No-one Locally Has the Money to be Able to Afford to Pay the Price

- Part 4: A Lifestyle Choice

- Part 5: In This Strategic Place

- Part 6: Women -- A Strong Partnership

- Part 7: Bringing Well-being and Survival Into The Household

- Part 8: Animals, The Landscape, and Prawns

Part 1:

Using the Crofts as They Were Meant to be Used

Brought up here in Applecross

Duncan Fraser: I’m Duncan Fraser. I'm originally come from 65 miles to the east of here. I met Kath, got married, I stayed. I haven’t been able to escape since then and have been brought into Kath’s way of thinking about sheep.

Kath Fraser: I’m born and brought up here in Applecross.

Fiona Mackenzie: I’m Fiona Mackenzie. My family is an Applecross family. I was back and forward here all my life. I wasn’t able to be here on a more permanent basis until three years ago when I left the job I was doing and am now doing a number of different things. But the important thing is it allows me to be here and I’ve got in cahoots with Kath -- well, and Duncan, because he’s had to do quite a lot of things as well about the sheep -- because I’ve always wanted to have sheep. We’ve got a little collaborative bit of work going on together.

In Motion Magazine: How does crofting come into your life?

Duncan Fraser: For me and Kath, on a social side of things, without the crofting and the legislation around the crofting, and the fact that our folks gave us their croft, we just couldn’t be here -- because otherwise we could not afford a site for us to build a house on. The house prices here are way more than anybody can afford to buy locally, who is working locally, because the wages are so low. There’s just too big a gap. The houses around here are about fifty percent holiday homes. Crofting is the only reason we are here. If it wasn’t for it, we wouldn’t be.

I come from an agricultural background and certainly believe that we need to be using the crofts as they were meant to be used. Otherwise, the environment that is around here, that people are coming to see all the time, would disappear -- because the environment itself is a man-made thing and if we don’t have stock on it, it will just go wild, all go into soft rush, and will not carry the diversification of animals that it does with us doing actual agricultural activity on it.

From the point of view a making a livelihood -- not that great. But it does keep the freezer full.

Kath Fraser: With beef.

Duncan Fraser: I’m not allowed to eat sheep.

Kath Fraser: I don’t know what to add to that really. I was born and brought up on a croft and we always had sheep. We never had cows. It was Duncan, (turning to Duncan) your farm was more cow oriented, wasn’t it? He’s the one that likes to work with the cows. I like to work with the sheep. At the moment, we are trying to find a way of doing less of the selling for meat and perhaps moving more towards doing something with the wool so that we can move away from constantly just selling lambs for meat, which is what I am not so keen on doing.

Felting and fleece

In Motion Magazine: What would you do with the wool?

Kath Fraser: Fiona has been away on a course learning how to do felting and things like that. I’d like to learn how to do it as well.

In Motion Magazine: Felting?

Kath Fraser: You turn the wool into felt. You can make all sorts of things. You can make bags. You can make hats. You can make anything with it, basically.

Or, another alternative would be to sell the fleeces as rugs but without them being sheep skin. You just felt the back of the rug, and you felt the back of the fleece. You sell them straight off the sheep as a rug because at the moment the price of wool is -- for the type of wool that we have -- it’s about eighty pence a kilo, which is not a lot because it costs one pound twenty to get a sheep sheared, and you need quite a lot of wool to get a kilo of wool.

Crofting is a way of life – for me anyway. I’ve always known it and it’s what I do.

Quite keen on the wool idea

Fiona Mackenzie: Again, I was lucky because the croft was in the family. My father had it, and grandfather did, and my father gave it over to me, when he was still alive, in 2007, and I was working in the Central Belt then. (Editor: the Central Belt is an area in the center of Scotland stretching from the east coast to the west including Edinburgh and Glasgow and the majority of the Scottish population.) But I got into the habit of starting to (grow) potatoes, at least, to start to spend some money on fencing and tidying up the sheds and things like that.

The sheep, because I wasn’t here permanently at that point, I couldn’t really see how I was going to manage to get into the sheep. But then we had this opportunity in that Kath had a lot of bottle-fed lambs a couple of years ago and it was a good solution – we had eleven. I bought some then to start and it worked out that Kath would look after the sheep when I wasn’t here. I could do a bit more when I was here.

And then we got the idea of getting something that was a bit more unusual, so we decided to get Herdwick sheep, which are a good compromise because they are quite hardy. They do very well in our conditions here and they are quite interesting. We got a sheared flock of them.

So, Kath has got their sheep and I’ve got my little gang of my own sheep. And then we’ve got the sheared flock but we are just running them all together. Again, like Kath, trying to think of a way of making money out of the sheep that doesn’t involve them going off for meat is quite attractive. I’ve been quite keen on the wool idea as well.

I think at the moment we’ve got a lot of ideas about what we might do. We’ve got to then try some of them out, and see how we can go with them. I think we might be able to do two or three different things on a small scale – things that we could do in our sheds without any huge investment, maybe a bit of investment, bits and pieces of equipment. There’s a lot you can do that’s using, as Kath says, the natural species.

Part 2: Animals and Land Management

In Motion Magazine: How many people live in this area?

Fiona Mackenzie: About a hundred and fifty, seventy. Under two hundred in the census.

In Motion Magazine: Do you think it’s a viable community size?

Duncan Fraser: At the moment, I’m doubtful. I don’t think that with a school roll as low as it is and the fact that so much of it is older, rather than younger people, it makes it much harder. But the problem is it comes back down to housing, jobs, and opportunities.

Fiona Mackenzie: ... You’d like to see being confident that the school would increase in numbers and these are kind of tied in so there is a thing about being some urgency, about trying to find some more ways on the house model.

Kath Fraser: The thing that I would be worried about is that the crofting way of life, as in having your animals, that way of life, will disappear because the people that get the crofts will not have the same connection back to the way that crofting has been. In the future, it will just turn into allotment-type things. There will be no animals and the landscape will change completely. There will be no land management as such, anymore, I think, if there was no animals. Ever since I was a young girl, the amount of people keeping sheep has dropped because the crofters that were active when I was younger have all grown old and have sold their stock. And the people that have taken on the crofts from them have not had the interest in keeping the way with animals.

So, that would be the worry that I would have of this community. It would be that in fifteen- or twenty-years time it’s completely unrecognizable as to what it was twenty years ago because there will be no animals left. The loss of the animals will be, in my opinion, a complete disaster for the place.

Fiona Mackenzie: And it would mean that it wasn’t that attractive a destination for a holiday, if you think of it, because things would be so out of order, very quickly.

Part 3: No-one Locally Has the Money to be Able to Afford to Pay the Price

There’s not the availability for young people

In Motion Magazine: A big difference between you and Finlay is you are a different generation. Can you talk a bit about that? I’ve been told that there are less young people involved than there used to be but it looks as if, well, a) you are here, and b) you are trying to develop another business that goes along with it in order to make it viable.

Kath Fraser: It’s never going to be a viable living on its own, crofting.

Duncan Fraser: Finlay is in a different position. Finlay is in a bigger croft. The croft here, the extent of our good ground -- and actually between me and Kath we’ve got two crofts -- is a hectare. So, a croft here is just over an acre – much more allotment size than anything else. (And) some folk here are using their crofts here pretty much as allotments as a way of growing vegetables and fruits. They have no animals.

The animal thing for us is, quite a bit of it, a lifestyle choice. I’ve worked with cattle all my life and I would therefore like to continue to do that. I get pleasure out if it and we get meat for the fridge.

But, actually make any money out of it? – No. For me and Kath, our main income comes from other activities. I’ve got a digger. I go and do work for other people. Kath has another job as well. Money that helps keep the croft going is coming in from outside.

So, yeah, it’s a lifestyle choice. Partly, as well, because we’ve got young kids. Something that both me and Kath have grown up with, is working with animals. It’s something for them to grow up with as well -- whether they like it or not.

One of the Fraser children: I like working with sheep.

Duncan Fraser: You see! They are buying it already.

Kath Fraser: Also, the other thing about less young people in crofting is, a large part of it is, a lot of crofts are still owned by absentees. There’s not the availability for young people to get into it. Whereas, if there was, there would be a lot of young people interested in crofting.

In Applecross itself, we do have a fair few young people with -- well, a couple -- my cousin just got a croft of his own. He’s in his early twenties and he’s got chickens, turkeys, all sorts of birds and a few sheep. And there’s another family just up the road. They’ve got a croft quite recently as well, but they’ve no animals or anything yet, But I think they do plan to get one cow for milking, and maybe a few sheep.

So, I think a lot of it is down to the availability of crofts and the ability to get into it.

Duncan Fraser: There are plenty of people who we know who don’t have crofts who would be interested in getting a croft for the same reasons as we have one.

In Motion Magazine: People that live here or people who live in the city?

Duncan Fraser: People that live here that managed to get themselves a house, or that may have started off by coming here for work and then getting work-related accommodation. Some of them have moved into caravans ’til they could find a house and then have got rental accommodation until they could find a site or some other way of getting to their own house. That tends to be the path that tends to follow.

There isn’t an easy way in -- unless you meet somebody like Kath (laughter) -- if you want to come and live here, because there isn’t that access to housing. And there isn’t that many jobs and opportunities here.

A lot of that is down to, as well, the fact that the land ownership is quite restrictive.

One family that owns it all

In Motion Magazine: You mean a few people own it all?

Duncan Fraser: There’s one family that owns it all and there’s assured tenancies in the form of crofts.

Holiday houses

In Motion Magazine: And the visitor-type, the vacation houses, they are actually crofts that have been converted into private property? How did they escape the system?

Duncan Fraser: A lot of them would have been originally a house on the croft and then it was taken off the croft and then sold. Taken off the croft by the family so that they retained the house, and then eventually it comes onto the open market, maybe a couple of generations later. (At that time,) it’s somebody from outside who buys it because no-one locally has the money to be able to afford to pay the price for it, (and) then it becomes a holiday house.

Fiona Mackenzie: The one next to me is a really good example because my family and the original family that owned that house – we were together there for decades and decades -- and then the family that owned it, exactly what Duncan said, de-crofted the house.

The croft is still in that family but the house then was sold. I think we are now in the fourth (owner), this last time it was sold. ... (And) she sold it last year and when she sold it, it was marketed as a holiday house. I mean it wasn’t even advertised in the way that anybody local might have felt it was for them. (Editor’s note: Since this interview was conducted, Fiona Mackenzie reports that this house next door to hers has been sold again.)

In any case, as a local house it’s quite limited. Once you market a thing and you make it sound a holiday purchase, then people are looking at it (that way). It’s been bought by a guy who lives in the south of England. I mean, he’s a pleasant guy and all of that, but that’s a typical situation.

In Motion Magazine: So, did they change the system to allow people to de-croft?

Duncan Fraser: It was always in the system because … although the house was on the croft ground, there was always the opportunity to de-croft some of the croft ground so that you could build a house, so that your family could build a house.

Kath Fraser: Say for old age, ill health, or whatever, you had to give over the croft to somebody else. If you didn’t de-croft your house then that house would be owned by that other person, all of a sudden, and not by you anymore.

When you build a house, if you don’t de-croft it then you only own the actual house, rather than the ground it’s on. It’s not a very secure tenure. You really need to de-croft it. And (also) you can’t get a mortgage unless you de-croft the land before. They’ll not give you a mortgage on just a croft house.

Duncan Fraser: Because technically the croft and the croft house belong to the estate and you have an assured tenancy. ...

(Another example would be) they would have been big families, so, potentially, the elder son would have got the croft. That meant the rest had to go and find and make a living somewhere else. and a lot of folk did that. You then end up with these family connections all over the country and when the parents died, (and) maybe the eldest son had also gone, the croft was left to somebody who wasn’t here.

(Then,) because of the historical battle to get the rights of crofters, and trying to give us that security of tenure – because, historically, prior to this you’ve got the Clearances, and then after that you’ve got the estates trying to turn crofts into farms, and assume them all, and put people off the ground -- this legislation came in and it was very strong. These people come with a real sense of, “This is my ground. I’m going to hold onto it. I’m going to do whatever it takes to hold onto it.” And, to a certain extent, we still have that. The family connection to this spot is very strong.

They’ve left the area because that is what they had to do, but they still have this connection to the land and they don’t want to give that up. So, they hold onto the croft. They hold on to the croft house. And anybody who sensibly de-crofts a croft house from the croft (does so) because that gives you possession of it, because otherwise if you die and there’s no one to take it on, it goes to the estate. The estate get possession of it and that’s the last thing you want because the estate historically has not been good to you. You are not going to let that happen.

Part 4: A Lifestyle Choice

Common grazings / community-based

In Motion Magazine: Do the crofters in the area make decisions together or do you each make decisions on your own?

Duncan Fraser: This is the Toscaig Township. (Editor: The Applecross Peninsula townships are: Ardheslaig, Kenmore, Fearnabeag, Fearnamor, Cuaig, Lonbain, Applecross Bay & Shore St, Milltown, Camusteil, Camusterrach, Culduie, Ard Dubh & Toscaig.) There’s a number of townships as you go up along the coast. And there’s a Common Grazings Committee and each croft has a half a hectare of in-by ground, fenced ground, which is your actual croft. You then have rights to use and graze animals on a further thousand hectares of common grazing. But that common grazing is basically rock and heather.

In Motion Magazine: Can you use it for your sheep and cattle?

Duncan Fraser: We do. The nature of our sheep and cows are such that that’s what they’ve got to be able to survive on.

Kath Fraser: And they do survive on it very well. The breed that we have does very well on that land.

Duncan Fraser: We chose appropriately.

Fiona Mackenzie: The common grazing thing can work very well. Ours is pretty good. We do discuss things, and fence repairs. It takes a long time to get everybody to agree but generally I would say in our township it’s quite functional. I think in some other places there have been, not necessarily in Applecross, but in crofting townships, there have been some terrible debacles around disagreements.

There have been controversial things that have happened here. For example, there’s always a situation where somebody was very keen to give over a site that he’d been using for a crofting purpose to build a house for someone who was going to come and live in the community. ... The house was built and then what happened was that individual then sold it on for a huge profit having got his land. That was very controversial ... . I think the motivation behind it was probably perfectly positive, it was just the way it didn’t work out. ... But in general, I mean, we are working in a collaborative way about the sheep, which is in an old-fashioned kind of way. If people have got equipment and other people need to use it then people lend and share things like that. It is quite good from that point of view – quite community based.

Having a croft doesn’t make you a crofter

In Motion Magazine: Is that what people mean when they refer to the culture of crofting? A combination of individual and collective activity?

Fiona Mackenzie: The way of life as well.

Duncan Fraser: There is quite a lifestyle choice actually in the whole, “We are going to croft.” There are some folk who have a croft and the croft has essentially been a way for them to get accommodation in the area because that has allowed them to get a croft house, build a house, or things like that, but they don’t necessarily use the ground.

Kath Fraser: Yes, just having a croft doesn’t make you a crofter.

Fiona Mackenzie: But the lifestyle thing is quite … well, like yesterday, I do other bits and pieces of things as well, so I was busy in my little room there doing some work and then Kath phoned and said, “Well, we are going to move the cows up the road, do you want to give us a hand?” So, off I went and did that. That was about an hour and a half between the bits and pieces we did on that and then I came back and then got on with my other work. And it’s quite nice that, that kind of working with other people, doing things to suit the weather. And it’s flexible.

In Motion Magazine: (And often) in a non-crofting part of society, if you need help you have to pay for it?

Fiona Mackenzie: Exactly.

Kath Fraser: For the crofting (though), you don’t get a steady income from it. The only income you get from it is once a year, or whatever, at sales you get from the market when you sell them (your livestock) in the autumn. That’s your income for the year.

Fiona Mackenzie: Unless you are deviating from it and doing some of the things which we might be doing.

Kath Fraser: But that’s exactly why you can’t really make a full-time living from crofting. Unless you have an enormous amount of animals -- which we wouldn’t be able to have here because we just don’t have the amount of ground -- you just can’t possibly make enough money once a year to keep you going all the way through to the next autumn.

Maybe then ...

In Motion Magazine: Is that because of the over-arching system that you are tagged on to? The market system as it were.

Fiona Mackenzie: I suppose in the old days, if you went back a couple of generations, you would probably have a fisherman in the family. You’d have somebody who did sheep. You’d swap over those things to keep the family going. Maybe then you would have a lifestyle that enabled you to stay in the place with a few of the family doing different and complementary things. -- (Though) you’d still have the problem about housing that we talked about, because we talked about the oldest son with the house. -- And they’d grow basic vegetables. They’d catch fish. They’d salt fish for the winter. The salt-meat.

Kath Fraser: They were a lot more self-sufficient, certainly, than the people are now because they had to be. There wasn’t the transport links that we have now. Everything was pretty much by boat.

Fiona Mackenzie: Sea links rather than road links.

In Motion Magazine: Do you think that lays the basis for having a village that survives together? In the past or now?

Kath Fraser: Certainly, back then I would say community spirit was a lot stronger than it is nowadays because people worked together a lot more and I was going to say there were less people but there was probably more people. The school roll has gradually just fallen and fallen and fallen. The school roll at the moment is eight and when I was in school here there was over 20. And when my dad was in school here there was probably about 50.

… (but) there’s no work here for people. It would be nice if more people moved here because there would be more children in school and things like that, but there’s nothing for them to do, and there’s nowhere for them to live. That’s a major problem because, do you start with housing and people will come but there’s no work – so they leave? Or do you start with the work, then there’s nowhere for them to live? It’s a complete Catch-22.

In Motion Magazine: Would it help if the government provided healthcare and other services to make life more convenient?

Kath Fraser: Well, we have a healthcare system. We’ve got a brilliant healthcare system here. We’ve got a good school. The things that we don’t have are housing and jobs. A lot of the jobs here are tourism-related. There’s some fishing -- not a lot, nowadays.

Part 5: In This Strategic Place

In Motion Magazine: So, actually, working on your croft doesn’t do it?

Kath Fraser: No.

Fiona Mackenzie: I think that’s where one of the issues about land ownership and the estate as the strategic body around the place is quite important because I think if there was a desire -- and I’m not saying it would be different if there was another arrangement because actually I don’t think any us have got ideas of what another arrangement would exactly look like -- but at the moment they are in this strategic place without much of a strategic input.

In other words, you don’t get an impression that they’ve got a sort of idea about it being a great tourist location, or it being whatever. There’s a sort of a void. I think it would be more helpful to have a way of creating more of an idea about what the future could look like in more of a strategic way. It might then enable you to put together housing and employment opportunities that were tailored together. Because, as you say, if you’ve got one and not the other.

There’s been a lot of work done to try and get more affordable housing but it’s not coming together. I think there are jobs that could fit quite well with this kind of community where the people could maybe support different things with common skills. If there was a desire to be a bit more strategic, I think we could come up with ideas.

Owned by the community

Kath Fraser: In the summer holidays, we went to Harris in the Outer Hebrides for a week and out there they have the west side of Harris and it is owned by the community. It is not owned by a trust or an estate like we have here. They have amazing ideas about how to get people to come there because there was a point at which they were going to lose their local primary school because the roll was dropping and so they implemented this system where they got some house sites which they put up for sale at extremely low value.

Have you ever been to the Outer Hebrides?

In Motion Magazine: No.

Kath Fraser: Well, there’s this place out there called Luskentyre. Luskentyre Beach is listed like in the top ten beaches in the entire world and so they are selling sites next to this beach for £10,000 whereas normally you’d be looking at £80-, £90-, £100,000 to get these sites.

Anyway, they’ve got these for sale and this point system so that anybody who is applying to buy the sites has to earn enough points so that they can choose exactly the right people. You get a lot of points for having young children, having skills that the community needs, having a job before they come here.

You get this system where you get the right people to come in and they also have to agree that they are not going to sell the house for 15 years, or something like that, and that they will put their children into the local primary school. And that way, you end up getting people that you know want to come and live in that community with that lifestyle rather than somebody who is looking at it from a, “That would be a place to get a good house site,” and, “That would be a good business to do a holiday house.” That sort of thing.

I think if we could do something like that here, that would be fantastic.

Fiona Mackenzie: And there is no reason that we couldn’t if the estate was part of that. In fairness to them, they have been trying a bit of consultation set of events, so maybe out of that maybe something like this would come. But certainly, with more activist partners in something like that.

Kath Fraser: The estate owns the whole place, right? Whenever affordable housing things come up, it’s always the crofters that they come to, to see if they can get a little common grazing to build the affordable houses on -- rather than building them on the estate grounds somewhere, where they’ve got thousands and thousands and thousands of acres that they could build all this housing on.

Part 6: Women -- A Strong Partnership

In Motion Magazine: What has been the role of women traditionally in crofting. Has it changed? What is going on now?

Fiona Mackenzie: I think that women have been really in hardy in crofting during the years – very influential I would say.

Kath Fraser: They’ve always been involved in some way or another. I suppose in the olden days …

Duncan Fraser: … they ran the croft and the men went fishing.

Fiona Mackenzie: Spinning.

Kath Fraser: Yes. Although the men would do most of the gatherings, going out to the hill and getting all the animals in, and that sort of thing.

Fiona Mackenzie: We’ve got some original pictures around and you’d see them with the peat baskets. So, the man would be doing the so-called heavy work but they’d be doing a peat basket on the back.

Kath Fraser: My granny used to chop the wood and everything. Even when she was 92 she had a huge axe, chopping away at these massive logs that I can’t do because I’ve never had to do that. My grandfather was a fisherman so he was away all week fishing, sometimes for longer than a week. She was at home with six children, doing everything, doing the washing in the burn. We have it extremely easy these days compared to the way that they lived.

Fiona Mackenzie: But interestingly, I suppose what we are describing, I suppose it was quite a strong partnership. … (though) in terms of my grandparents, my grandfather would expect my grandmother to lay out all these clothes, especially for Sundays. He’d go mad if the cufflinks weren’t there for his shirt.

On the other hand, actually, the day to day, they were quite a partnership. They were both very busy doing, keeping things working, quite heavy work.

Part 7: Bringing Well-being Or Survival Into The Household

In Motion Magazine: Are there other people coming up with creative ideas, like what you are talking about with the wool?

Kath Fraser: Yes, there’s lots of people around doing different things.

In Motion Magazine: Out of necessity? Or that’s what they would rather be doing? Or a mixture?

Kath Fraser: A mixture. There’s somebody who started out doing vegetable boxes and things like that which I think is actually a pretty good idea. I’m not quite sure how it didn’t carry on. She had a croft and she used to sell boxes round to the houses locally. Nobody else around Applecross does the same thing – oh well, there’s (one family), they’ve got their own Gotland sheep and they make their own wool and they make all sorts of woollen products.

Duncan Fraser: And they have animals, and they do sheepskins as well.

Kath Fraser: They’ve got a little shop. If you’re going around the coast you might actually see it. It’s called Croft Wool (see photo). It’s worth a wee look.

Duncan Fraser: We also used to do direct selling of meat. We used to have pigs and we used to sell those around. And it was quite successful. We did it, again, in cooperation with another crofter because the ground is not very good for pigs. It goes very muddy and the pigs destroy the structure often quite quickly so you need to keep moving it. You need more ground. But, we got it up to a certain size.

It was quite successful for us and it did actually give a bit of an income. But then two or three other people started doing something similar and it was just too much for the size of the community. There was other things going on for us as well at the time so we down-sized and came out of that.

Kath Fraser: Going back to the Outer Hebrides again, this holiday that we went on was a great source of inspiration because we were driving about one day and we saw this sign for Croft 36 Shop. So, we decided to go and investigate what this was and all it was was a little tiny shed at the side of somebody’s house with an honesty box in it so you could just pay what you ... There was nobody there to run it or anything and they were selling homemade bread, seafood. You could order meat. You could order fresh fish, like that. They did a home delivery service of meals. They had a menu. You could order your dinner. They had a big vat of soup. Just help yourself to hot soup. They didn’t do crafty things.

I thought, “What a fantastic idea.” Something like that would work brilliantly here. We thought we might look into doing something like that. But we’ve got loads of ideas -- you need to think about it and come up with one idea that is going to work. If we did some of the weaving, felting, and things like that, we could do something similar and have a little shed with produce for sale.

In Motion Magazine: So, most people are self- or small-business employed?

Fiona Mackenzie: You find that most people here have four or five jobs, a portfolio of things, and some people, maybe some people do holiday cottage cleaning, working at night, teaching, building, stoneworks. (One person) does breakfast at the hotel. She does some holiday cottage cleaning. She does art, she’s an artist, and he does music. They’ve built a fabulous cottage which they are using as a rental income within the grounds of their one place. They’ve got a mass of polytunnels. I would think that for vegetables they pretty much grow their own. That’s quite a good example, as well -- the variety of things that are bringing well-being or survival into the household.

Trained to do the job

Kath Fraser: One thing that we haven’t really said much about is the actual animals and the difficulty of having animals in such a remote place.

One of those things is if you are wanting to do meat production, the main issue that you have is that you have to drive them all the way to Dingwall to the abattoir and then drive it all the way back again to distribute it.

If there was a more local solution to that where you had a local or even a mobile abattoir where it was a local person that was trained to do the job -- because that’s one of the main issues that I have, is I hate the thought of selling my animals to the market where they may then get bought and taken off and have to endure an enormous journey down to the north of England, or somewhere, to then be slaughtered in some horrible slaughterhouse somewhere where the people might not have the same level of animal welfare that I would have.

It would be easier for me if it was a more local thing and that would perhaps change my outlook slightly on producing meat and it might be a more sustainable thing for around here because then more people would perhaps do that.

Duncan Fraser: … if you create the demand locally for animal carcasses -- because somebody is going to turn them into crofter’s pies, or whatever -- then people will work to fill the demand.

Part 8: Animals, The Landscape, and Prawns

In Motion Magazine: Concerning the care of the animals, is it just as much about the land?

Duncan Fraser: If you look after the animals, you look after the land.

In Motion Magazine: Can you talk a little more about the idea of the landscape that you were talking of earlier?

The Animals

Kath Fraser: In the olden days, or even now, but not so much now, you need the animals to go out in the summer so that you can grow forage for the winter so that the hay grows and you can cut it in the summer, dry it on the fence, and then you’ve got that for the winter. And, if you didn’t do that, if the sheep were in all year, there would be no hay to cut and the ground wouldn’t get a chance to clean.

Just by putting them out on the hill, they get a change of diet, -- which is also good for them and they do do well on heather -- and it gives a chance for the in-by grass to grow so that when they come back in in the autumn there’s good grazing for them.

In Motion Magazine: What about the other animal life, like deer and mice? Do you feel it’s an integrated system? It gives the landlord the opportunity to shoot them?

All: (Laughter.)

Duncan Fraser: If there wasn’t any large animals to graze the grass, what would happen is the grasses would break down, the tougher species would come through more, and you’d end up with tussock grass. It would grow in lumps. The ground would become uneven and then it would start to waterlog as well and then the soft rush would come in. And then you would just have soft rushes everywhere. You might then get birch colonizing it after that.

Essentially, at that point, the structure of the ground will become such that it’s constantly wet. There’s no drainage and all that will grow is the soft rush. It’s not good for animal grazing. It is good for ground nesting birds to have a habitat to nest in but not for anything else. It would just become a blanket - one plant.

Anything that could live on soft rush would do alright while it was there but then there would be nothing there when it wasn’t. You wouldn’t get the strains of spread through the seasons for providing feed for animals. Anything that didn’t survive well with soft rush wouldn’t have anywhere else to go.

Having animals on it, the grass gets grazed. We maintain that field there, the field boundaries, and they don’t regress to just being soft rush. That’s what gives the varied habitat which allows for the animals a better chance for survival, an environment for them.

We are lucky in Toscaig because the areas which are just flat grass are not huge areas. From that point of view, there are trees, there’s rough ground, everything else. There’s a wide variety of environments around us. There’s plenty of places for ground-nesting birds. There’s plenty of places for tree-nesting birds. We have areas for small mammals: voles, mice, all those. They gain in the fact that they come in and they use the buildings that we have, that we are using for our animals for winter shelter as well. And they get the benefit of spilled feed and things like that for the winter, plus also their own stuff that they have been putting away. (Additionally) there are predators of the types of badgers and pine martens and foxes about. So, they get to prey on the smaller animals.

So, yeah, I think the fact that we’ve got animals helps the environment that’s here.

Prawn fishermen: selective of what they take

In Motion Magazine: Would you say there are fisherperson crofters?

Duncan Fraser: Yes.

In Motion Magazine: What do they do?

Duncan Fraser: Mainly shell fish. The days of the herring fisher have long gone. They went with the big trawlers coming in, big modern trawlers. Kath’s father used to be a herring fisherman when it was still ring-netters.

Nowadays, just off the coast here, we’ve got a military range which has in some ways been a benefit because there has been a navy out, which has ... no-one’s been allowed to fish in it, so none of the dredgers are coming in to pick up prawns -- which are all coming in from outside, prawns or scallops ... . None of the prawn fishermen have been able to go into it. It’s a breeding place which colonizes everywhere else.

The prawn fishermen around here, they only take them if they are mature prawns. They only take mature crabs that have reached a ripe size. Everything else goes back in – back in alive so it can grow. Anything that’s carrying eggs goes back in alive so they can breed. They are selective of what they take.

But, there is part of the year when the dredgers can come in and they just take everything that’s on the seabed. And, if it’s not what they want, it gets thrown back in. But my that time it’s dead. There’s active pressure to try and stop that. In Loch Torridon they’ve managed to do that. Admittedly, they did do that by going and dumping old cars in the best of the dredging spots. A dredger stops dredging quite quickly when it starts losing its nets every time.

But the problem now is the military range has just gone (and announced), “We’re expanding and we are taking that much.” The area that they are allowed to fish in has been reduced substantially and it is already that busy out there with folk fishing with creels (editor: baskets).

Fiona Mackenzie: A quite good thing that is a new thing is that both the places that you can eat here try and buy as much as they can locally – so, some of the fisherman provide food to the eateries here. And meat -- you know crofters sell meat as well.

In Motion Magazine: Is that part of the national movement of nutrition?

Fiona Mackenzie: I think it’s just pragmatic. Local people saying, “What’s the point in sending it away and buying it in from Taiwan, frozen, when we’ve got them here.” There’s a mixture because some of the fisherman take much of their stuff away. It gets picked up from a central point and goes away to wherever it goes away to. But some of them do the local.

Duncan Fraser: Certainly, for the pub and the Walled Garden, it’s good advertising. It’s a good selling point, and that means the quality of stuff they are getting they are sure of because it’s just come out the sea that day.

Published in In Motion Magazine February 17, 2018.

Also see:

- Interview with Iain MacKinnon

The Cultural Norms of Crofting:

The Recovery of the Story and Voices of the Economy, the Understanding, and the Life of a People

Edinburgh, Scotland

- Interview with Fiona Mandeville of the Scottish Crofting Federation

A Hegemony of Helping and Looking Out for People

Kyle of Lochalsh, Ross and Cromarty, Scotland

- Interview with Finlay Matheson

Crofting: The Concept That There Should Be Lights in the Glen Again

Strathcarron, Ross and Cromarty, Scotland

- Web site of the Scottish Crofting Federation

- Interview of Adam Payne of the Landworkers’ Alliance

Change in Rural Culture, Small Farms, and Hedgerows

West Dorset, England

- An Interview with Kate Fletcher

The Lives of the Users of Clothes

"What the future looks like"

Santiago, Chile

- Interview with Gregory Cajete

Science From A Native Perspective:

How Do We Educate for A Sustainable Future

Albuquerque and the Turquoise Trail, New Mexico

- Interview with tibusungu 'e vayayana

Political Deputy Minister of the Council of Indigenous Peoples

Reconstitute Different Tribes, Different Peoples in Taiwan

Taipei, Taiwan

- Interview with Jadwiga Lopata and Sir Julian Rose

Of the International Coalition to Protect the Polish Countryside

The Small and Middle Family Farm:

A Base for Poland to be Independent, and a Base for Good Quality Food

Stryszów, Poland

- Interview with Yanet Alarcón, Mauricio Parada, and Pedro Huayquillan

Defending the Ancient Trails / the Culture

Chos Malal, Neuquén Province, Argentina

|