|

Hog Wars: Part 2 The Corporate Grab for Control of the Hog Industry by Patty Cantrell, Rhonda Perry & Paul Sturtz An Unprecedented Family Farm-Environmentalist Alliance Takes Hold

At the same time PSF was spilling manure, it was also hemorrhaging cash. Its main Wall Street backer, Morgan Stanley, had advanced the company $6.5 million to meet a junk bond interest payment. Lincoln Township and other PSF neighbors wondered if they would be left with massive cleanup costs if PSF left its lagoons behind along with junk bond debt. But even with all these developments, MRCC and the task force did not presume legislators would automatically see the wisdom in their Good Neighbor legislation. The months preceding the 1996 session were spent gathering input, organizing strategy and preparing action plans. MRCC leaders collaborated with the Ozark chapter of the Sierra Club to develop its legislative proposal. An unprecedented family farm-environmentalist alliance was taking hold. Two task force leaders, Roger Allison and Terry Spence, traveled the state and met with task force groups to reach complete consensus on the 12 Good Neighbor policy points. The groups prioritized its top five objectives: Public notice and hearings on CAFOs, bonding, setbacks from residences, prohibitions against construction in drinking water and Conservation lands and compliance with clean air laws. "Every group was prepared and had people out there working," Perry says. "We were all accountable to each other; not off on our own."Weekly strategy sessions enabled the task force to maintain a coordinated and focused approach. Ken Midkiff of the Ozark chapter of the Sierra Club provided up-to-the-minute bulletins from the Capitol and helped synchronize the messages of the Sierra Club and other environmental groups with the task force. Conference calls generated vital information, direction, and a blueprint for action. "We'd get eight or 10 current articles each week or two and pass them out to our groups and to legislators," says Margot McMillen of Callawegians Opposed to Factory Farms. That kept fresh letters and telephone calls coming to representatives and senators from every part of the state. It was these small but strong doses of popular perspective that kept the grassroots message growing, McMillen says. "We wanted a constant reminder that 'these people are still around.' If we had sent each legislator a huge packet of information, it would have just been tossed. But somebody was there every day giving them flyers or articles or cartoons and pushing the same five points....We were trying to put in as much presence as the full-time lobbyists were."

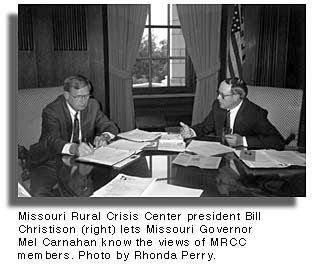

Barbara Brazos of Callaway County was among those stunned by the anti-democratic wall. "They were leaning back in their chairs, laughing among themselves and appeared to be literally looking down their noses at people." Did this throw the volunteer grassroots lobbyists off course? Not at all. The committee's show of disdain for the thousands of people that MRCC and the task force represent actually strengthened the resolve. "I called every single person the next day, and they were pumped up to see the whole process through. It really made people think about building power," says Paul Sturtz of MRCC. That's because they also saw a little confusion behind the arrogance among the legislators who were used to the established agriculture groups' version of vertical integration. "The rural legislators were absolutely flabbergasted," says Ken Midkiff of the Ozark chapter of the Sierra Club. "When they also started hearing from individual farmers and communities, they got mixed signals. "It was clear the Farm Bureau was no longer speaking for its members." So even though they tried to continue arguing that stricter oversight of the large operations would hurt family farmers, something had changed, Midkiff says. "They no longer had the argument that it would hurt family farms" because family farmers were among the most vocal CAFO fighters. This fact would carry the task force and its message through the coming rough propaganda days and onto the Senate floor for a final showdown. The first public relations contest came when the House Agriculture Committee voted to endorse a bill that could have been written by the industry. The task force responded with an onslaught of letters to every legislator and the governor.

This article is taken from the Missouri Rural Crisis Center publication Hog Wars - The Corporate Grab for Control of the Hog Industry and How Citizens are Fighting Back. |

| Published in In Motion Magazine - December 6, 2001 |

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2020 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

The momentum and publicity generated by the rally and the march helped bring together new community groups who were forming and joining MRCC's task force as Cargill, Tyson, Murphy and others expanded their operations. A series of hog waste spills in the fall - six from PSF facilities and two from Continental Grain - also raised people's awareness. The state Department of Natural Resources (DNR) responded with emergency regulations and a moratorium on construction in sensitive watersheds.

The momentum and publicity generated by the rally and the march helped bring together new community groups who were forming and joining MRCC's task force as Cargill, Tyson, Murphy and others expanded their operations. A series of hog waste spills in the fall - six from PSF facilities and two from Continental Grain - also raised people's awareness. The state Department of Natural Resources (DNR) responded with emergency regulations and a moratorium on construction in sensitive watersheds. And it was because members and supporters were so engaged that they did not crumble at the first sign of politics as usual. At the first House Agriculture Committee hearing on February 7, 1996, more than 70 task force members packed the room early. Industry insiders were left standing in the back. Family farmers repeatedly testified how unlike real farmers the factory operations are. Despite the overwhelming show of support and evidence, however, committee members showed little respect for the people's input.

And it was because members and supporters were so engaged that they did not crumble at the first sign of politics as usual. At the first House Agriculture Committee hearing on February 7, 1996, more than 70 task force members packed the room early. Industry insiders were left standing in the back. Family farmers repeatedly testified how unlike real farmers the factory operations are. Despite the overwhelming show of support and evidence, however, committee members showed little respect for the people's input.