|

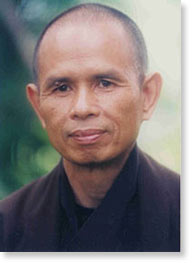

An interview with Thich Nhat Hanh

Community-Based Art and the Practice of Compassion and Mindfulness Eloise de Leon Escondido, California

I witnessed implosions due in part to unchecked egos but also due to a failure to remain true to community-based missions. In one of the centers, new policies were developed that weakened artists, participation in the center and control over their work. Un-met pleas for dialogue were followed by petitions, marches and a three-year boycott that is still in place at the time of this writing. I visited Thich Nhat Hanh, an internationally known Vietnamese Buddhist Monk at Deer Park Monastery, with a question fresh in my heart -- how to respond to the conflict in my artist community. After all, I knew the current strategies to build community, audiences and the organizational funding base. But how do you respond to your respected colleagues that have become embroiled in organizational conflicts? I thought that Thich Nhat Hanh might give some direction. I have heard him say “do not run away” from a crisis. Instead, use the crisis to practice compassion and develop peace. I met with the Venerable Zen Master at Deer Park Monastery in Escondido. Known worldwide for his social and political activism, Thich Nhat Hanh entered monastic life at the age of 16, and began his activism during the Vietnam War in Saigon when he founded the School of Youth Social Service. It was a relief organization to re-build shelters, establish schools, medical services, and services to people displaced by war. He was exiled from Vietnam in 1966 but his efforts for non-violence continued, moving Martin Luther King, Jr. to nominate him for a Nobel Peace Prize in 1967. Eloise de Leon: I am confused that artists working to build community could become enemies with each other. Taking a position seems to make it worse. How can one respond to such conflict? Thich Nhat Hanh: Any attempt to change a situation either politically or otherwise should be based on the transformation of our own consciousness. If we don't know how to listen to ourselves and to each other we are not going to go very far. It is clear that you have to listen to yourself, your own suffering, your own aspirations. You have to understand yourself to some extent, and to the people in the communities, to their deepest desires, their suffering. That kind of deep looking will bring about more understanding of self and of the community. Understanding will make acceptance and tolerance and compassion possible. With that kind of understanding and compassion possible, the quality of life in the community will improve. You learn to look not with individual eyes, but with the community eyes. Because the collective insight is always deeper than individual insight. In the Buddhist community, the sangha eyes are always clearer than the individual eyes. (Note: a sangha is a group people that meet regularly to study and practice Buddhist teachings. Lay practitioners do not need to convert to Buddhism but may use the practice to enhance their lives and existing spiritual/religious practice.) Thich Nhat Hanh: You have viewpoints, you have experiences, you have insights. You try to offer the sangha all that you see and you feel, and you allow all the people in the sangha to have the same opportunity to express their insights, their views, their experiences. So, practicing listening deeply to each other is very important and practicing using the kind of speech that can make other people understand you. With pride, with arrogance, with irritation, you cannot help the other people to understand you, your insight, you view, your experience. So, there are two things to practice: listening deeply with compassion, and trying to express yourself with kind, loving speech that can convey your insight. It's very beautiful. As you continue to progress on the path of mutual understanding and acceptance, you become an instrument for social and political change. If you do not succeed in your community, don't hope for quality, because without that base of operation you cannot achieve much. People are motivated to do things, there are plenty of them, but without the capacity of listening, of understanding, of being compassionate, what they do cannot help. They can make the situation worse. So, goodwill is not enough. There must be the capacity of understanding, of compassion, and of working together in harmony before you can hope to do something. What I propose is that you go back to your community and use your talent of listening and of loving speech to help other individuals to improve their quality of listening and talking and learning how to surrender their individualism to the collective insight. Then the quality of life of the group will improve. If you are happy together, harmonious among yourselves, then we can move forward to change society. Peace and social change must begin within your community.

I always tell my monastics to be authentic. You can share with people what you have already practiced. What you have practiced in harmony, tolerance, mindfulness, joy and peace within the community. If you don't have these things, don't go out, because you have nothing to share. Even if you can speak with eloquence that is not what people need. They need something true. It’s like a psychotherapist who is not capable of living happily in his own family. How can he help a patient? Or a politician who cannot listen to his own wife and children. How can he help other nations? This is our experience of practice. Eloise de Leon: Can you speak about people's attachment to suffering? Sometimes people are so identified with their struggles that they are unwilling to release them.Thich Nhat Hanh: It is very important to come out of your suffering and there must be ways to get out of that kind of suffering. Suppose you suffer because there's so much violence and despair in you. If you know nothing about the art of transforming your anger and your despair, if you don’t have a real taste of happiness, how do you expect to help other people not to suffer? We need to reduce the amount of suffering within us and in our society. Life has meaning only when you see a path that leads you and other people out of suffering. In the Buddhist tradition, understanding suffering is very important. Suffering is the first noble truth. If you look deeply into it, you can discover the second noble truth, the making of the suffering, the cause, the root of suffering. When you understand the nature and the root of your suffering, the path of emancipation can be seen. To suffer and not to understand your suffering -- suffering in that case has no meaning, has no value, has no use. Understanding the nature of your suffering, you begin to see the path leading to emancipation. When you have the path, you have the energy and the courage to practice and to help other people. And in that case, suffering is helpful. But if you don’t understand suffering, if you are drowning in the ocean of suffering, suffering is not a very noble truth. You can’t be proud of your suffering because it does not help you. It does not help anyone. You must look deeply into your suffering and understand it. When you understand your suffering, you see the path of emancipation. People from all religious denominations and backgrounds have learned the technique of mindfulness taught by Thich Nhat Hanh. It is a practice of slowing one's movements, becoming aware of the breath and of the present moment, “I am at home. I have arrived.” The practice of mindfulness is key to cultivating peace in the individual. Thich Nhat Hanh’s newest book is “Teachings from the Lotus Sutra”. In it he teaches that every person has a Buddha nature and tells the story of the “Never Despising Bodhisattva” who shouts to the people who drive him away with insults and beatings,

Two special retreats will be led by Thich Nhat Hanh at Deer Park Monastery in Escondido, California this spring. “Nurturing the Creative Heart” for people in the film/television industry, March 19-21; and “Colors of Compassion”, a retreat for People of Color, March 25-27, 2004. For details check the internet at www.esangha.org or call (760) 291-1003. Eloise de Leon is an artist coach, writer and filmmaker currently living in New York. Her articles may be found in the Art Changes and Human Rights / Civil Rights sections of In Motion Magazine. Her website is: www.insightandjoy.com and her email is: eloisemargaret@gmail.com. Published in In Motion Magazine - January 25, 2004 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © 1995-2013 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||