|

Fighting hog factories in eastern Colorado

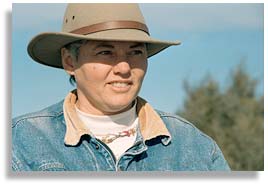

Interview with Sue Jarrett near Wray, Colorado

Sue Sheridan Jarrett is a rancher on the eastern plains of Colorado. She's also a "hog factory fighter" and an independent consultant for the Grace Factory Farm Project. She's a co-chair of USDA's Small Farm Advisory Committee on the national level and helps write policy recommendations for small family farms versus agribusiness and corporate farming. The interview was conducted just before New Year's 2001 by Nic Paget-Clarke. In Motion Magazine: What are some of the dangers family farms are facing here in eastern Colorado? Sue Jarrett: In my particular area of the Midwest, the market concentration issue is number one. We do not have access to competitive markets. When you have the consolidations of Cargill and Continental, or Smithfield Tyson trying to buy IBP, the federal government and the WTO say they see consumer benefits, we look at how they effect open markets. They mention that Cargill had to divest itself of some of its Gulf export centers to somehow keep the concentration from getting too bad, we look at it from the perspective of "I've got corn to sell and within a ninety mile radius every elevator I'm selling to is Cargill, Cargill and Cargill." That's market concentration. They are sitting on my local markets. If I've got a pen of fats to go and the only bid I get is IBP, IBP, IBP you know I'm now a price-taker instead of a price-setter. We work a lot on market concentration issues and how on the local level we have lost access. I used to have four or five guys bid on my cattle every day. Now I get one bid one day a week and a fifteen minute window to take it or leave it. That's market concentration. In Motion Magazine: How long has it been that way? Sue Jarrett: I've been on the ranch for seventeen years and it's gone from the level of several people bidding every day, to several people bidding every week, to a few people bidding a week, and now these last four years, I have one or two bids to choose from . It's either Excel or IBP. In Motion Magazine: So you really don't have any choice? Sue Jarrett: I don't. My only other alternative is the feedlot that we custom feed through. It feeds Mormons Mineral, which has an open contract with Monfort, which is now ConAgra. So, if I've got a pen of fats I can't sell anywhere else and I want to put them through the grid within a week's notice I can say I'm shipping this pen of cattle to the Mormon contract with Monfort on the grid. Which still isn't much of a choice. With fat cattle and fat hogs you are dealing with a commodity that has a window that it has to hit the market in. You can't hold onto that for three months and say "Well, I don't like the markets right now so I'll keep it." When you are dealing with animals and livestock there is usually a two or three week time frame that you can get that animal marketed in. Otherwise you are going to get docked for overages. They hit a peak where they are prime for butchering and after that peak you get docked for excess fat, or the animal goes off feed. A lot of times our government doesn't always understand this end of it. If you've got a bin of corn and you don't like the market you can store the corn and say I'm going to keep it and sell it three months later, but you can't do that with live animals.

Sue Jarrett: Right now prices are up on fats. They are not at parity, but they are up. In Motion Magazine: They are not at parity? Sue Jarrett: Parity is a concept similar to the idea that workers are provided a minimum wage. The government sets in law that you are going to pay a worker five dollars and 65 cents an hour, or six dollars and 15, whatever we are up to now, and that everybody's labor is worth that. In the agricultural world, minimum wage is parity. Cost of production plus cost of living to keep up with inflation. I say that in the family farm sense we should have a level of production that we are guaranteed our parity on a family-farm size level of production. Anything produced over and beyond that, anything produced in a mass volume to control the markets, should not be allowed. A year and a half ago hogs hit ten cents a pound. Through Iowa and the Midwest corn belt, a lot of family hog producers went out of business. Their cost of production is anywhere from 35 to 40 cents. Some are a little cheaper, some are a little more, depending on the particular farmer and his inputs. This devastated a lot of family farmers The problem was there was so much control of hog production by the packers themselves. Smithfield has their own hogs. Seaboard has their own hogs. Hormel has contracts with different hog producers. There was no open market. They didn't need the hogs that everybody else was putting on the market. Once those packing plant floors are filled, they don't have to go look for animals to buy. If they can keep their packing plant chain moving with their own pigs they never have to buy from an independent producer. The Packers & Stockyard Act and anti-trust laws were created so that there would always be an open and affordable supply of food. You know how people say America has a cheap food policy? America doesn't have a cheap food policy. America has a cheap commodity policy. There is a significant difference between cheap food and cheap commodities. In Motion Magazine: What is that difference? Sue Jarrett: Commodities are things that are mass-produced for industrial production. Food is something that is produced to meet a consumer's taste or demand. You'll hear oftentimes "well we have to produce hogs this way because that's quality control and we are producing quality for the consumer." They are not producing what the consumer wants. They are producing what the packing plants want. The same-size animal to go through those automated chains faster and faster. You never have an odd-sized animal that throws everything off. That's quality control from the packers' perspective not the consumer perspective. Cheap commodities means we are going to mass produce these pigs; we are going to displace all the environmental costs and every other cost we can to produce cheap pigs to go though that packing plant; and the consumer doesn't have a choice because there is no labeling. When they displace the cost it is to the communities and society around them. Corporate hogs in eastern Colorado In Motion Magazine: How have the corporate hog farms that have shown up in your area impacted family farms? Sue Jarrett: I live in an area that didn't have a lot of independent hog producers. Back in the '40s and '50s, Colorado raised as many hogs as we did in 1998. The difference in that in the '40s and '50s we had lots of little farms all over Colorado, in the mountains, on the plains, everywhere. Every family farm had some milk cows and some pigs and some chickens and some cattle and raised some crops. It was very diversified. Your hogs were your cash crop because you sold your litter of pigs twice a year. A sow tends to have two litters. So, you had a few to sell to keep your cash flow going. We saw the production of hogs drop off in Colorado significantly until the corporate hogs came in. When the corporate hogs came in we saw our production hit the same level that it used to be at our highest producing time fifty years before. Only now instead of them being spread over thousands and thousands of acres with a few hogs on every farm, we have several thousand hogs on two to five acres. And the land just can't sustain the waste from those hogs. On top of that, the hogs are confined in buildings where in the old days they were always free ranger and open air. Now they are confined in buildings which are temperature controlled, climate controlled, no movement. Animal movement is as minimal as possible. They often don't have room to turn around. In fact, the sows don't. They are kept in cages where they can only stand up or lay down through the gestation and birthing cycle. They are taken out for the breeding cycle and then put back in.

You are talking about a different level of production. It's called industrial production. It's not sustainable production. Anytime we have industrialized any segment of production, whether it was vehicles or plastics or steel, we have confined activities to a narrow area, but these hog producing facilities are not able to contain or handle their waste products. The pollution controls are always the last thing to come on in any industrialized process because as long as they can displace their pollution costs to the community they locate in, they can make a lot of money. When they have to start paying for the pollution costs that cuts in to their bottom dollar. Corporate ag only cares about the bottom dollar. They can't care about people or animals or anything else. They can only care about how much money they are making. In Motion Magazine: So in eastern Colorado, you have more of an environmental problem than an economic concern because there wasn't that much hog production in the first place? Sue Jarrett: Right, but what they are doing displaces hog production from other areas. Nationally or internationally, you have a certain level of production to meet a certain level of demand. If they've brought pigs out here to produce they've displaced pigs from somewhere else. They haven't created new packing plants to handle extra capacity. But they didn't displace local people. We had a few that have gone out of business because they've lost local markets but we were never a big enough production area to have very good local markets. It's been more the environmental costs, the degradation side of things, in this particular area. In Motion Magazine: Can you talk some more about the environmental aspect - for example the concern for the Ogallala Aquifer . Sue Jarrett: On the eastern plains of Colorado we don't have much surface water. We are pretty much an arid and dry area. Almost everyone out here relies on the Ogallala aquifer for their sole source of drinking water, irrigation, agriculture. The towns draw out of it. When the hogs came out, based on what little we knew of the concentration of them, we got very concerned about them. We are in a sandy loam soil which means when it rains, it pours, and the water just goes right through that sandy soil. It just leaches right on down. We were really concerned about the lagoons being designed right. After they get the lagoons full, to be able to keep capacity in lagoons, they have to pump down the lagoons periodically and put the effluent through the circular sprinklers we have out here. We were very concerned that they have enough land to do that. That they not over apply. That the lagoons not leach or break and get into our ground water. I'd like to debate over which is harder -- to clean up or to monitor -- surface water or ground water. Surface water you can drive up and see when it's getting polluted. You can sample it and you can start work on cleaning it up. Ground water is down there. I'm on a private domestic well. The Clean Water Act doesn't protect that and the Safe Drinking Water act doesn't protect it. The Clean Water Act only protects surface water. The Safe Drinking Water act only protects wells that service 25 people or more. So nobody is out here telling me everyday I turn on the faucet to get a drink of water or brush my teeth - "Your water is safe Sue. Go ahead and drink it." I have to now periodically test it. I grew up as kid in this area, and ever since I can remember nobody ever worried about water problems. The Ogallala was one of the purest sources of water there was because by the time the water leaches down into the aquifer it has gone through a natural filtering system. Now, in addition to the corporate hog farms, we have a super fund site up in Nebraska about two hours north of me where there are fabrication shops, and industrial, chemical and dry-cleaning by-products which have leached into the ground water. How are you going to clean it up? How do you clean up ground water? You can prevent it from getting contaminated but how do you go clean it up? If it gets destroyed, polluted, how do you clean it up? And who's going to tell me when it hits that point - because nobody monitors it. The cities monitor theirs but in the forty miles between the towns nobody knows what is going on. There were enough studies out about the pollution and the leachability that it didn't take me long to figure out that I was dealing with a major environmental problem. An once they got up and going, then we hit the secondary problem -- the stench. And it's horrendous. I had a day ... I had been outside working that morning and come in the house and ate a brunch - I'm notorious for not eating breakfast or lunch, but I'll eat about mid-morning -- took care of some messages and some work and was headed back out to do some work. When I had come in the hogs were not smelling. When I hit the door to go back out, I don't know if the wind had changed or what, but I opened the door and went down to the bottom of the steps and grabbed my nose, threw my coat over my head and went running. I was about to get sick to my stomach. It would hit days where it was that bad. Not all the time, but yes, it would hit days when the girls would go to walk to my folks' and you'd see them with their coats over their head running as fast as they could to get from one house to the other because it would be so awful. My oldest, who doesn't tend to say much about this issue, I know it's bad when she leaves to go out of the house and within a few minutes she's coming in the door. "Mom!" Without her ever saying anything else I know immediately that it's stinking. She's gone out of the door and come back in totally irritated. The next words will be "the pigs stink". It takes a lot for her to complain because when I first took the issue on, she got targeted by some of the kids whose parents work at the hog farm. She was made fun of and harassed because her mom was fighting and "picking on them", and "going to cost their parents their job". She was friends with them and so it was an emotional struggle for her to be friends with them while I'm fighting the hog farms.

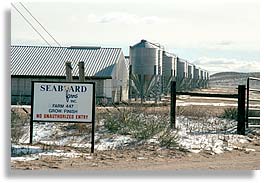

In Motion Magazine: You say lagoons. What are they? Sue Jarrett: The cess pools. The pits. In Motion Magazine: What goes in those pits? Sue Jarrett: The waste from the animals and everything else that falls between the cracks. Out here the hogs are kept in buildings with pits underneath them. They are on slotted floors. Periodically they hose down the buildings and flush the waste that hasn't fallen through the floors down into the pit. Then they pull a plug and it's piped out into what they call lagoons. They are nothing more than a shallow hole in the ground with a piece of plastic. It's all this processed waste-water, manure, urine, needles - anything that falls through the floors goes in there. Disinfectant. Whatever. It's all in there. It's flushed out into a couple of acres they call lagoons. It just sits there. In the Spring and in the Fall, they pump the effluent, as they call it, through center pivots for nutrients for the crops. They pump it out through these big center pivots on to the land for fertilizer. I call it dumping grounds but they say they are fertilizing the ground. I say they are using it as dumping grounds to get rid of their junk that's untreated. It sits in those holding pits until it's piped out. In Motion Magazine: And that is to grow what? Sue Jarrett: Mostly here it's corn. In Motion Magazine: And then that is fed to what? Sue Jarrett: The corn is harvested and most of it around here goes to the CAFO's (Concentrated Animal Farming Operations). We have a lot of cattle feed lots and the hog farms. Most of our corn is fed back to the animals and then the cattle graze the stalks for winter feed. The corn is harvested and put into elevators and stored for animal feed, mostly animals in confinement. In Motion Magazine: How many hogs are we talking about in this area? Sue Jarrett: Out my door, northwest, starting at two miles away, on up, is a 20,000 sow farrow to finish operation, which is 400,000 market pigs a year that they put through that system. And there are other hog farms in the county. I'm at the north east corner of Yuma county and what used to be D & D Farms is now Seaboard farms. We have Smithfield Foods south of Yuma. And we have several Alliance / Farmland contract growers in and around Yuma. In Motion Magazine: If you were to compare that concentration of animals to humans, how much sewage would that represent? Sue Jarrett: Conservatively, pigs produce two to four times the waste of a human. Some people will say seven to ten. But even two, if I've got 400,000 market pigs out my door, times two is 800,000. Counting the sows and nursery sites that's about equivalent to a million people. I would guess Denver is pretty close. If you think of a million people, or 16,000 people on two acres, which would be a pretty tall high-rise they would obviously have to have a full waste treatment system. But this is not treated at all. It's just flushed out into these holding pits and then pumped out on to the land. There is no treatment process to it whatsoever. Money, faces, and door-knockers In Motion Magazine: How did this become a statewide Colorado issue? Sue Jarrett: For a couple of years, as more and more people came on board, we tried to put some legislation through our state capital, through our legislation session. Both times we were beaten out by the cattle feeders organization, which we were able to find out not only represented the cattle feeders but the hog factories and the big dairies. They were basically the big CAFO, feedlot organization. They spent a lot of money to kill both of our bills in '97 and '98. After the session was over in '98, we challenged to put the hog regulations on the ballot and we created a coalition.

We put together a coalition of money, faces and door-knockers to get the message out that these things were bad, that they needed some regulations, and that Amendment 14 in 1998 was the amendment to vote for. The amendment passed. The amendment did not grandfather anybody in. It said new facilities had to be built to compliance and any existing facilities would have until July 1st of 2000 to put into place monitoring, controls. and protections. We are now in the phase where Amendment 14 is being enforced, which is why National Hog Farm is having to shut their doors. They didn't come into compliance. In Motion Magazine: Where are they? Sue Jarrett: They are up along Greeley, located by the ranch of the guy who had the money. In Colorado it's known as the battle of the billionaires. A billionaire with hogs fighting a billionaire with a hunting preserve ranch. They have fought since National Hog built their facility back in '89. In Motion Magazine: Is the amendment going to be helpful in other parts of the state? Sue Jarrett: It's helped already. Since the passage of 14, as we've worked to implement regulations, they have had to control their odor to the greatest extent practicable. Through the regulation process we determined that that would be a 2 to 1 standard at my house, which is one of the strictest air standards in the nation. Also, I have the ability to complain and the ability to file a citizen's lawsuit if they continue to impact my air. People out here, we don't sit in offices where our air is filtered. Our jobs are outside working, taking care of animals, farming, whatever. We were able to prove that living with the odor, one, does impact health, and two, is a nuisance. They have now started a test site and started controlling their odor . We still have odor days, but for the most part we have seen a significant reduction in odors because of Amendment 14. In Motion Magazine: What happened to all those small family farms that were here 30 years ago? Sue Jarrett: They've slowly been weeded out. Every once in a while we go through a farm crisis. We went through the '70s farm crisis. We went through the '80s farm crisis, and the '90s farm crisis. There's a farm crisis somewhere in every decade. Every time there is a farm crisis you lose a percentage of the family farmers and the farmer beside him buys up and gets bigger. It's called the "get big or get out" mentality. At the national level - there's only so much protein production and consumer demand for protein whether it's beef, chicken, or pork. There is only so much market to fulfill. There's only so many square feet and number of animals that can be slaughtered a day. There's certain capacity limits on what controls production. If you see the packing plants controlling their production, by either owning the pigs outright or contracting to have them always delivered, they don't have to go into the open market to buy. At the same time, consumers aren't provided labeling which says this animal is hormone free or anti-biotic free, or this is a free-range animal, raised out of confinement, or whatever the case may be -- and that is hurting us economically. If you go and produce the animal right, who says you are going to get a premium for it when you still have to use the same packing plant as everybody else. It's got to be processed and MADE ready for the consumer to eat. Things are involved and in depth when you get into the vertical integration and concentration side of these issues. In Motion Magazine: The "get big or get out" approach, is that responsible for each of these ten year cycles? Sue Jarrett: A lot of it. But also they are driven by our national policy on agriculture. There's a couple of economic and sociology professors, back in the Iowa and Illinois, who have studied the "get big or get out" philosophy and the agricultural policy which is driving the consolidation of agriculture. To maintain the economic growth and industrial production that we've had in this country, we have had to continually move people off the farm. Also, we've increased the use of technology on farms. We need less people to do the work because now machines do it. We don't need horses and people out there picking the ears off by hand. We have machines that will go and do it. Not only do we have a machine that will go and pick four rows, we have machines that will pick twelve rows of corn, and it doesn't take but one man to run such a combine. You swap labor for industrialization. Even the hogs. When the corporate farms came in they said, "We're bringing jobs". Well, corporate jobs tend to displace more jobs than they bring because by their very nature they're industrialized and automated. You need less employees to do the work. They hate it when you bring that point up. They might employee more people here when they came to this area, but they displace other people from hog production in another area. Not more efficient dollar-wise or food-wise In Motion Magazine: Do you think it's true that larger farms are more efficient than family farms? Sue Jarrett: The only way a larger farm can be more efficient, economically, is to displace a large part of their costs - and in this case their environmental costs. If corporate farms truly had to pay for the cost of handling their waste and were not using my back door as a dumping grounds then the family farmer can beat them hands down. The family farm is more sustainable, and doesn't have to dish out the money to combat environmental degradation. The family farm has a much more efficient cost of production. There's studies out there on that now. For years, all we've ever seen is industrial studies which said that bigger is more efficient. The point of the matter is that it takes so much capitalization to raise the animals this way that you have to have a fast payoff to pay for the buildings, etc., Whereas for the family farmer, the cost of his business venture to get into hogs is to go buy the breeding stock and provide the labor. You don't have to go and build a million-dollar barn to raise a hundred thousand pigs in. Rather, you go out and fence in a piece of land, buy some feed, and provide the labor. You run your pigs and save your litters and go for it. Industrialization by its very nature is not more efficient. It's more mechanically efficient, but it's not more efficient dollar-wise or food-wise. In Motion Magazine: Is there anything else you'd like to say? Sue Jarrett: Well, from a personal perspective, I've lived with industrial hog production out my back door. I've become an activist and stayed an activist because not only do I believe that my daughters shouldn't live with the problems we've encountered with this sort of neighbor, but I don't think anybody should. This is a horrendous way to raise animals. It's a horrendous way to produce food. It's not economically viable. It's not a quality product and should not be on the market. That's a personal opinion. It's not good for the environment. It's not sustainable. And then there's anti-biotics and hormones. To keep animals confined in buildings you have to feed them lots of hormones and antibiotics. Hormones are growth stimulants to make them grow faster, and put pounds on so that they are turned out that much faster. But just as with people, if you keep them in jails and concentration camps, if you keep them too close together for too long, sicknesses develop. You pass things around. Well, pigs are the same way. So they feed them more and more anti-biotics. We're very concerned about the antibiotic-resistant genes that are developing. I know in the medical community you hear that this is a big issue. They talk about doctors over-prescribing, giving people anti-biotics when they really may not need them. Well, we're feeding anti-biotics to animals not to treat sick animals and get them healthy, but as a preventive measure and to make them grow faster. That's not good science. We are losing some of our anti-biotics because we are getting disease-resistant bacteria out in the world. Even before I got involved in this, my oldest daughter when she was five, got very sick with a bug and we about lost her. She got a major infection and went onto antibiotics. I look back and I see that if those antibiotics hadn't worked I wouldn't have her here. Antibiotics are for treating sicknesses not for preventing sicknesses. And they should not be used as growth stimulants. I draw the line on that one and I fight that a lot. 40 percent of all antibiotics produced are animal feed additives. That's a large amount. And Florinquen and some of the newer ones that they have just developed already have bacteria resistant to them. It takes many millions of dollars to find a new drug and it's ridiculous to allow it to go into animal production when we might need it for humans. Especially when I can produce animals out here in a sustainable system without having to feed them antibiotics and hormones. Inform the consumers and let them have a true choice. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Published in In Motion Magazine April 1, 2001. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World || OneWorld / US || NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2011 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||