|

Immigration, Migration, And Human Rights

On The U.S. / Mexico Border by Roberto L. Martinez San Diego, California

California’s rich and colorful history is tainted by the treatment of the original inhabitants of this state. The Native American population was decimated throughout California in the last half of the 19th century. By the time Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, California had already been under Spanish and Mexican rule for nearly 300 years. An interesting observation was made in 1840, in what was then known as Alta California, by Pablo de la Guerra of Monterrey regarding the number of Yankee settlers moving into California:

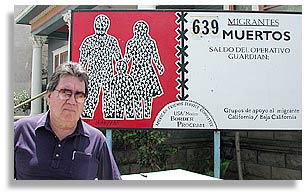

When the U.S.-Mexico border was created by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, ending the war with Mexico (1846-1848) there were about 75,000 Mexicans living in the U.S. By the time California became a state in 1850, there were already over 10, 000 in California alone. Mexicans living there. Agriculture was already one of the main sources of income for the state. However, Mexican labor was also responsible for the construction and maintenance of railroads, mines and ranchos during this period of transition. Mass migration of Mexican labor didn’t begin until after 1910 when the Mexican Revolution began. Discrimination against Mexicans was already evident when California entered statehood in 1850. Widespread racism and violence had erupted in 1849 when thousands of Mexicans flocked to California and Arizona seeking work in the mines and railroads during the gold rush period. However, nothing compares in numbers and magnitude to the massive raids, violence and deportations of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s by police and Border Patrol throughout California and other major cities of the Southwest at a time when Mexicans were being scapegoated for all the social and economic ills in the country. U.S. citizens, as well as legal residents, were deported along with suspected undocumented immigrants. In the 1940s, roundups and deportations of Mexicans were blamed on immigrants taking jobs away from servicemen returning from World War II. Today, police and Border Patrol still work together in many parts of the Southwest, including many parts of San Diego County, to violate the rights of both documented and undocumented immigrants. A case in point. In 1997, the police department in Chandler, Arizona, a suburb of Phoenix, rounded up over 400 Mexican people in raids that lasted five days. The police were backed up by the U.S. Border Patrol. Of those 400 plus people, only a handful turned out to be undocumented. The majority were U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents. This raid was reminiscent of the “repatriation” raids of the 1930s and 1940s in Los Angeles. A 35 million dollar lawsuit was filed against the City of Chandler. If Proposition 187 had passed in 1994, it would have been legal for police in California to detain for the Border Patrol anyone they “suspected” of being undocumented. Today, California is the sixth largest economy in the world (according to the World Bank, 1999). Part of that distinction can be attributed to California’s 30 billion dollar agribusiness, which has been sustained over the last hundred years by the labor of several ethnic groups, including Mexicans, Filipinos, Japanese and African Americans. However, Mexican laborers have endured this hardship the longest. They have also been the most persecuted by politicians, law enforcement, vigilantes, hate groups, and abuses by employers. This is where the irony lies in the passing of legislation, such as the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA), to grant amnesty to thousands of farm workers. For years immigrant rights groups, such as AFSC, have criticized the hypocrisy of our immigration laws. Since 1924, when the first immigration reform and control act was passed by Congress, the U.S. has been re-creating, re-defining, and re-inventing the border in order - not to seal it - but to regulate labor for U.S. businesses, such as agriculture, and later, high tech jobs. The INS, with the support of Congress, passes laws legalizing a select number of immigrants, then turns around and passes another law to get rid of them, such as the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA). This law is considered by many to be one of the most un-American, unconstitutional, immoral, anti-family laws ever passed in the United States. The worst aspects of it, such as being retroactive, by punishing legal permanent residents for past crimes, has resulted in the deportation of tens of thousands of legal residents. Thousands of families have been torn apart by separation from their spouses. Several bills have been introduced this year to correct this mean-spirited law. Probably, no other issue has raised more passion or controversy than the U.S. Border Patrol strategies presently being used on the U.S.- Mexico border. In California it is called Operation Gatekeeper. There are three others: one in Arizona, called Operation Safeguard; another in El Paso called Operation Hold the Line; and the fourth in South Texas called Operation Rio Grande. These strategies were specifically and deliberately designed to funnel northbound migration through open areas, such as mountains and deserts where migrants can be more easily apprehended by the U.S. Border Patrol, thus exposing them to “mortal danger.” Nearly 2,000 men, women and children have died crossing the U.S.- Mexico border since the first operation was launched eight years ago - an average of one a day. In California, nearly 700 people have died since Operation Gatekeeper began in October of 1994. We are now averaging about 140 deaths a year in California. Prior to 1994, we only documented 23-24 deaths a year, yet the Border Patrol continues to blame smugglers and the weather. They are partially right, but the numbers and the facts still speak for themselves. In conclusion, a Government Accounting Office (GAO) report released this month concluded that, “Operation Gatekeeper and the other strategies are resulting in an increase in deaths from exposure to either heat or cold .” This is a conclusion we arrived at almost seven years ago. As we say in our press releases, “cuantos más?”, “how many more?” How many more people must die before it is considered too many? |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Published in In Motion Magazine August 28, 2001. Also read:

|

||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2020 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||