|

An interview with Suzanne Lacy

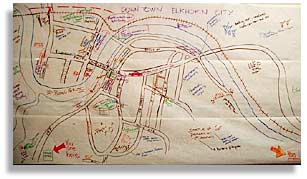

Art and Advocacy Part 2 - Breaking all kinds of frames Interview by Nic Paget-Clarke near Elkhorn City, Kentucky

The following interview with Suzanne Lacy (part 2) is part of a series of interviews with some of the members of a group of 25 artists from around the U.S. and Canada who went to Kentucky and Virginia to participate in the initial stages of a multi-year, multi-site community art project sponsored by the American Festival Project. The American Festival Project is based in Whitesburg, Kentucky with Appalshop, a regional community arts center. Also see: Fred Campbell, Rodrigo Duarte Clark, Harrell Fletcher, Shannon Hummel, Stephanie Juno, John Malpede, Robbie McCauley, Nobuko Miyamoto. The way in which people hold history In Motion Magazine: Did the people in the community have suggestions for some of the content of the pieces they have in mind? Suzanne Lacy: A lot of the suggestions, at this point, were around history, a theme I don't find as intriguing as a lot of people do. However, I did find that the way in which people hold history in that region, the meaning of histsory in their lives, and the reasons they wanted to express their sense of history, were very interesting. The connection of history to place. The relationship of place to land. To family. To oppression from outside opinion, prejudice. To pride. In this area there are the Potters, the Raineys, other families who have been here for decades, centuries. There are families that have settled here, been here forever. Their lineage, what their great-great-grandfather did here, is important to the people who live here. The Confederate War. The stories. The stories themselves are much less important to me. They are not my kin. It's not even that, actually. The stories of my own kin aren't particularly interesting to me. I guess its not the way my aesthetic operates. But The very fact that history is important to the people here is of interest to me. I am curious about how the concept of history operates in people’s lives. What does it mean to them? How does it connect them to personal meaning, to a sense of belonging? Does it affirm values, create identity? In Motion Magazine: So these were some of the things that came up in this meeting last night? Suzanne Lacy: History, and more. The kind of things that came up were, "How can we focus on our community heritage and who we are and represent that? Our music. Our culture. Use art as a means to represent ourselves within the the larger environment of the region?" They want to develop eco-tourism. They don't want to over-develop in terms of industry. They want to grow a little but not a lot. A lot of people care about the environment here, though it means different things to different people. Elmer, the video artist (he is now being known, at least by us, as a video artist) wanted to show us the strip mine. He cares a lot about what is happening to the forests, the land. Now, people kept saying all week, "You know we haven't been terribly influenced by the coal industry in this tiny little area that we live in. It's near the national park. The coal is too far beneath the surface and is hard to get to that and the natural gas.” But, it became very clear after a while that the issues with natural resource mining don’t surface very quickly here because so much of the economy of this region is dependent in one way or the other upon these industries, even if they aren’t mining here. A lot of us who have been working for years are political in our orientation. We want to grapple with political issues. Here in Kentucky, it’s a sure bet that if you put any ten political artists like myself in this area for a week they are all going to ask "Ah, strip mining. Let's talk about that?" Over the course of the week we began to peel away the layers: "It's our culture. We are proud of it. We don't want outsiders coming in and telling us who we are but we do want to welcome people in." It didn't come out immediately as an issue. But when you start to peel away the surface, it does start coming out. We began to get more and more information about the issues of coal mining and gas mining. At a certain moment I had one of those very personal “ahas!” when I realized that every piece of land, except this federal part right here that we're sitting on (in the Park), is extremely vulnerable because almost nobody owns the mineral rights to their land. That means you can be sitting on your land and there could be coal underneath it, and once the coal is gone there might still be natural gas, but basically other people own that part of the land. They own the land a few inches under your feet and the access to get to it. I got the sense of this little town, almost floating on this great sea of uncertainty, with incredible mountains all around it. Natural beauty. But, at any moment the mineral industries could say. "Oh, we like what is under your feet" and start digging the hell out of it. When we go into a community, often what we do as artists is to look for an issue. "Ah, a prison." "Ah, teenagers." Those issues come in and out of art fashion largely based on media exposure, I think. When homelessness is big news, that is the time when you'll find a whole lot of artists galloping in to do homeless projects. Not that strip mining and a whole host of issues related to coal mining aren’t critical issues for this area. But the more complex and problematic thing is to try and work within a community, maybe one that doesn’t uniformly believe that strip mining is that much of a problem. Or, like the Heritage Council seems to believe, maybe the notion of developing a community sensibility and a regional empowerment is what is first needed, before tackling more complex and sometimes divisive issues. How do you care enough for a region to say, which the Heritage Council does, "This is how you get to the issue. You first develop community. You first develop sensibility and pride and the experience where people will want to protect their environment and feel enough ownership so that they will stand up together to protect their land if or when it ever becomes threatened." On the other hand, there are a lot of community “feel good” projects that don’t stand up aesthetically or conceptually. We are used to public and community art that is either issue-oriented or expressive of some simplistic notion of “can’t we all get along?” I think that it's complicated and difficult to do art that reflects where the community is at and at the same time maintains a sense of political rigor. In Motion Magazine: You work in Oakland, a large city. Do you see any particular difference in the way people are looking at art?

But I think it would take very little to stretch that understanding. People are quite receptive to difference, and I expect that that would extend to their notion of what is and is not art. Already they are busy creating a play in the graveyard about people buried in the graveyard. They've already trans-located the play from the stage to a public site. It’s still traditional theater: in that graveyard they are trying to find the histories of the people buried there, so that someone can represent that person and memorize a text that reveals who that person is. They're pushing out of the spatial frame but they haven't pushed out of the type of historical narrative that's pretty common in the theater. But, then, one woman said, "I think I ought to dress up like a ghost and lurk around." Immediately I had this image of her literally haunting the town for a period of time….through photos, video, appearances, whaterver. The seeds of boundary breaking, form creation, on a populist level are to be found in idiosyncrasies. People in a small town often embrace their idiosyncrasies. Their idiosyncratic people. "That's Larry. He's the one that does that. He's crazy but we've known him all his life and so it's ok. He can be crazy with us." There's a lot of flexibility in a small town for idiosyncrasies, bizarre behavior, as long as you are known. Wherever that is possible so is breaking expectations of art. When I was a kid in the San Joaquin Valley of California, I was Larry's daughter and if I wanted to do something weird in directing the school play or decorating for the school prom, people went along with it. "Well that's what Larry's daughter does." Here in Elkhorn City, we found a great tolerance for our ideas, but we also felt like we were “known.” Accepted into the community and regarded with curiosity, quickly assigned the priviledge of “that’s what they do; they are artists.” We became in a remarkably short time, known, or at least accepted quantities, and I predict because of this there would be a great deal of latitude here about what we could do as artists. In Motion Magazine: How to use or appreciate art in a city as opposed to a rural area? Do you think that the region’s poverty effects the way that art is developed? The superstructure that supports art? Suzanne Lacy: You mean like building museums and galleries? In Motion Magazine: Or whatever. If art is singing maybe you don't need money. Suzanne Lacy: As we all know, there is an Appalachian culture -- a musical culture, a theatrical culture, a strong craft culture. (I don't know much about the painting or sculpture here, but no doubt it exists in a unique form.) There is a regional culture that is unique to this area, like there is in almost every region. I suspect the existence of culture isn’t related to money. You should see the art in Haiti. But you would have to ask people here. They would speculate on that better than I could. I didn't see, speaking of that, a whole lot of evidence of poverty in Elkhorn City. In Motion Magazine: A little more on the process of the week. How much did you know about how it was going to proceed? How do you think about how that worked out? Suzanne Lacy: I knew almost nothing about how it was going to proceed. I think we just arrived and things started happening. We were introduced to this place and that place, this person and that person. The Heritage Council had done their homework finding people for us to talk to. But they were also extremely flexible if we decided we didn't want to talk to anybody or if our group of four wanted to go in different ways. We floundered for a while. But I don't think it was unusual. The most complex thing for me was trying to figure out what way I could be of use. Usually when I do a project out of my own town, it's a bit more clear cut. If I'm invited to a place to do an artwork they know what kind of art I do and they want me to come do something like that with them. That we will do a project together is pretty much of a given. Here we wondered, "Are we consulting?" "Are we helping them think through things?" "Are we working together as a group of four collaborators?" "Are we coming up with separate ideas as individual artists?" In Motion Magazine: Was that good not knowing that? Suzanne Lacy: No. It was neither good nor bad. It's just what it was. It was a little frustrating but if you are a workaholic - and a lot of community artists tend to be workaholics - you want to try to help people and do a lot in one week. When I am given a charge by a community or institution within that community, to come up with a project, I visit the place, spend a week, absorb a lot of stuff and start producing images and ideas by the end of the week, generally out of conversations with people. I run them by the people and together we make selections. Here I didn't want to come up with a lot of images because I wasn't sure if that was what I should be doing. I didn't know if the people here wanted it. And I didn't know if the other artists I was staying with, artists that I may or may not have been collaborating with, would want it. It was sort of like. "After you." "No, after you." All week long. It was a little awkward - but it was alright. In Motion Magazine: You were happy with how it worked out? Suzanne Lacy: At times I was bored; I wanted to do something. My idea of a good time is to invent art projects. But for the most part I think it has been fun. A good experience in just being part of the pack. I'm not clear what my relationship to this place is or should be over time. I think there has been some vague notion that we might develop projects here but I don't know if that meant only in our region, or in collaboration with the others in our group, or by ourselves, or only if we are invited back. I think that will become clear in the next couple of days. I suppose the most important thing is whether the community would want us to come back. Its kind of like waiting to be invited to dance. My experience of the process has been that everything has been very well organized. Very thoughtful. Whether it was an accident on Michael (Hunt)'s part I don't know. But it feels like it was very thoughtful. Very intelligent as a general scheme. If we all did art, would we end strip mining? In Motion Magazine: I was going to ask what has art got to do with solving problems but you have already dealt with that in how the Heritage Council is looking at developing the community as a whole. Suzanne Lacy: And, in general, art has a lot to do with solving problems. Art affirms identity. Art gives voice. Art expresses difference, and it expresses consensus. Art brings up issues. It's a rather unencumbered opportunity or framework, offering opportunities to step outside of the normal way of doing or seeing things. Art is a very reflective process. It allows for collective and individual reflection on issues, on processes, on relationships. People get a real high from participating. Stepping outside of what they normally do, and becoming architects and planners of time and space. I think art is a very interesting way, though not necessarily the most effective way, to create change. Do I think if we all did art would we end strip mining? Probably not. But not because of anything intrinsic with the making. Rather, it’s a matter of scale and resources. If artists had the scale and resources of the mining industry then of course we could stop mining. Art is supposed to solve problems but it hasn’t got even a small percentage of the resources that are commanded by the problems that we are supposed to solve. If I had what Sylvester Stallone has for a single movie -- money and talent and resources -- I could make a very large impact on a region using art. I could make as much impact as he does with a movie. But community artists never have those kind of resources. That's the real issue in terms of art and change. People are always comparing apples and oranges around art and change. The apples are an art project done on $20,000, the oranges are the multimillion dollar strip mining industry. The amount of resources make the efforts very different in scale and effect.

Published in In Motion Magazine October 31, 2000. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2020 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||