|

Dreamtime Keeper

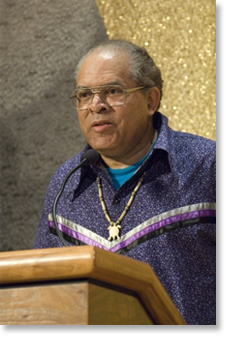

Interview with Native American Poet Ron Welburn Interview by Ja A. Jahannes Savannah, Georgia |

||||||||||

Coming Through Smoke and the Dreaming is his sixth book of poems. His collection of essays, Roanoke and Wampum: Topics in Native American Heritage and Literatures, was a co-recipient of the Wordcraft Circle Creative Prose: Nonfiction Award in 2002. He is particularly interested in the survival strategies of Native families along the east coast. An avid jazz fan, he is finishing a project on Natives and jazz. At UMass Amherst since 1992, Ron teaches Native, mainstream American literatures, western hemisphere fiction in translation, critical writing, and American studies. He also served as a chair of the Five Colleges American Indian Studies Committee and co-established the University's Certificate Program in Native American Indian Studies in 1997. After two decades as a pow wow vendor for the Native American Authors Project, Ron joined his wife Cheryl dancing at some pow wows in 2000, Eastern Men's traditional. Jahannes: What is your earliest recollection of an interest in poetry? Welburn: I’m sure I transferred my love of hearing family members tell stories and anecdotes to gaining a love of poetic diction has been a great influence. I also recall enjoying novelty poems as a child and teenager. Because I read a lot of history and autobiographies, I didn’t happen to pay close attention to poetry until late in high school when a double dose of poetry cultures caught my attention: a Folkways recording, American Negro Poets, I think is the title, owned by the family of a close friend, featuring Langston Hughes, Margaret Walker, Sterling Brown, Gwendolyn Brooks, Countee Cullen and Claude McKay reading their own works; and the second was an anthology, The Beat Generation and the Angry Young Men. Yet, I continued to read prose. When I entered Lincoln University in Pennsylvania in February 1964, a year and a half after high school, working in the Vail Memorial Library got me exposed to Conrad Aiken, Denise Levertov, and Rainer Maria Rilke. I sensed a world opening up! Jahannes: What is the way in which you are inspired to write a poem? Welburn: Being of rural (Berwyn) Pennsylvania background, and always feeling displaced in Philadelphia where I did most of my schooling, the natural world more than urban life held more for me as a poet. Birds, trees, hillsides, streams, a romanticized perception probably. Yet, growing up in the city had its effect. I was once described as "a rural sensibility attracted by urban rhythms," those being largely jazz, then salsa. I need Dream Time; that's when I can best reflect and organize my ironical vision, or natural inclination to see relationships in the world around me honed by knowledge learned from my elders. When Melvin Tolson (1) visited Lincoln in 1966, he told a group of us budding poets (Sam Anderson, Fred Bryant, me and others) that you went to the city to see life and to the country to write about it. But that never sat well with me, much as I appreciated him. I made plenty of poems from life on and around campus. The birds, the weather changes, I could relate to that. We had some family members who lived in the area, so that connection just came naturally. Jahannes: After you began writing poetry, what obstacles did you have to overcome? Welburn: I don’t recall any. Maybe not having enough money to buy books by poets I’d have liked to have. But I made do. We poets on campus nurtured each other; and we had non-poetry writing school mates who encouraged us. Jahannes: What has been your best feeling at a reading of your poetry? What fed this feeling? Welburn: Foremost would be articulating my poems well without stumbling. I try to "orchestrate" the order of poems in a book and for a reading. I’d never be a poetry slam reader, I’m not that kind of performer; just an old-fashioned poet who has some idea of how to give a poetry reading as though it were a song or musical composition. Maybe this comes from listening to a lot of music from all over the world, and being an amateur musician and composer. Jahannes: What persons, events, emotions have fed into your poems you have decided should be published/read/shared? Welburn: I've written poems about hypocrisy on the government level and between ordinary people, about urban Indians hiding their identities, about the alignments in the heavens, love poems, about astronomical and ecological mysteries. I'm a longtime reader of Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentine writer, for his literary puzzles and ironies, and a few of my poems over the past decade or more invoke his perceptions directly or indirectly. Jahannes: How do you see the Native American experience and the African American experience in your poetry? Welburn: There's not enough space to write about this cogently, but I'll put it like this: There are blacks who are part Indian and there are Indians who are part black, and they’re not the same people, although many African Americans think they are. Jahannes: What makes them different? Welburn: The world views between the two peoples have some similarities and many differences; principally, Indians feel rooted to this "America" space that’s older than the idea of the United States and older than the name by many thousands of years. Our ancestors are part of the grass and trees. This is knowledge I grew up with from childhood, elementary school age; yet it took me a while to understand the "one drop rule," and that east coast Indians were not all removed as many people claimed because I was seeing otherwise. It is considerably painful to have one’s grandparent tell you: "We can’t be Indians any more. Just forget about it." Over the past 30 years I’ve met numerous people who tried to forget and then got lost trying to come back. I mean no malice when I say that the Black Consciousness movement had an adverse effect on Indian identity on the east coast and Southeast because it compelled many mixed-ancestry Indians to try to fit into African America; being Indian and/or proclaiming pride in Indian heritage angered most black folks I encountered. So, the poems I’ve composed about aspects of this interaction have been a bit bemused. My early twenties to early thirties was the time I more consciously identified as black; yet I could never shake off or wanted to relinquish my Indian heritage, and this upset many people -- I almost got into a fight right in my dorm room over it. I couldn't see wearing the African garb; since my hair grew profusely, in the early seventies I wore it in a semi-afro, but would get a regular non-afro haircut. I just didn't look right or feel right in a dashiki. Later, at pow wows for decades I danced inter-tribals and eastern social dances; then ten years ago when I began dancing in regalia (Eastern men's based on early-to-mid 18th-century style) my wife says I’m dressed in my "real clothes." In high school, and by some at Lincoln University, I was perceived as Hispanic, even Latinos in NYC thought I was one of theirs, and I guess I cultivated aspects of that look. In the long run, I think I had to experience that decade-plus of black identity to have a better understanding and appreciation of my personal Native legacy: how people got moved around, being run off our reservation on the Virginia Eastern Shore, living with apprehensions of children being taken from them to be put into boarding schools or up for adoption, and having bad memories of a whole lot of things. Things like that. Giving voice to those feelings by parents and grandparents, giving voice to the denials made about being an Indian while your hunting buddies were all Indians and doing things in a special way and demanding that I show deference to particular people in our community. And the people who quietly slipped off to pow wows; and the family we used to visit in an Indian community in Jersey without anyone saying the word Indian, or Lenape. So, I never felt that existential separation from an African motherland; but all my life, literally, and even knowing I have some black forbearers, I’ve had a great sense of loss of the country right under my feet. For the past thirty-plus years, a composite of all this has characterized the moods and feelings of my poetry. Jahannes: What is special to you about being a poet? Welburn: Being a poet keeps me situated in place, in time, in sensibility, and has been my most autobiographical of forms. Sometimes I wish poems could be published sooner; often, poems that have appeared in print, whether journals or my books, are two to five or more years old. But I’ve been fortunate to have the respect of many peers, especially among Native poets. Jahannes: Two of my favorite poems by you, of which there are many, are Bones and Drums and The Mirror and the Hollywood Indian because they speak so cogently about place, legacy and identity:

Jahannes: Thank you for so eloquently giving us a vision that so powerfully peers into the heart and soul of America.

Also see:

|

||||||||||

|

Published in In Motion Magazine November 24, 2010 |

||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World || OneWorld / US || NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2012 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |