|

Oscar López Rivera:

A Hero Comes Home

Barack Obama commutes the Puerto Rican

independence fighter’s sentence

by mariana mcdonald

|

|

|

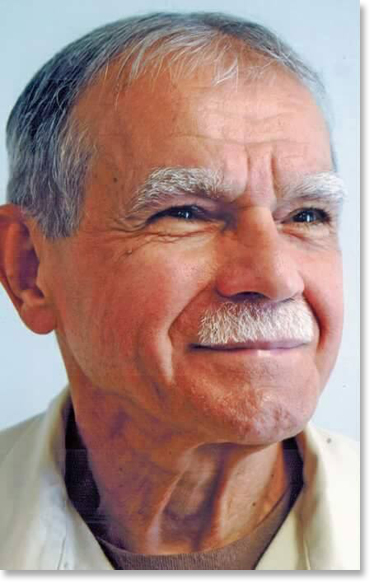

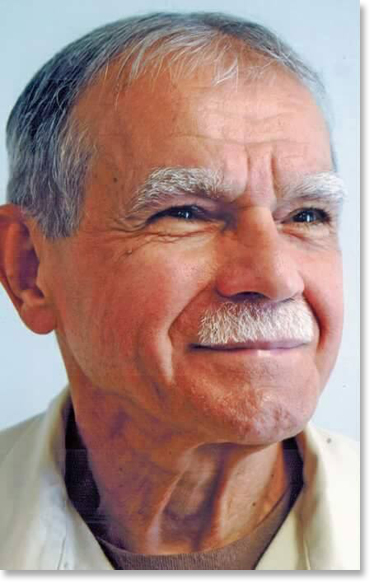

Oscar López Rivera, Puerto Rican independence fighter.

|

|

|

|

López Rivera’s daughter, Clarisa López Ramos, overjoyed by news of the commutation.

|

|

|

|

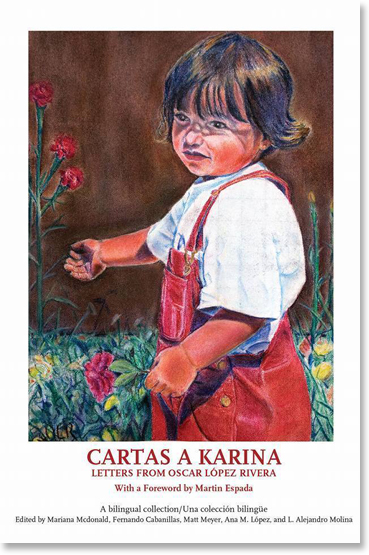

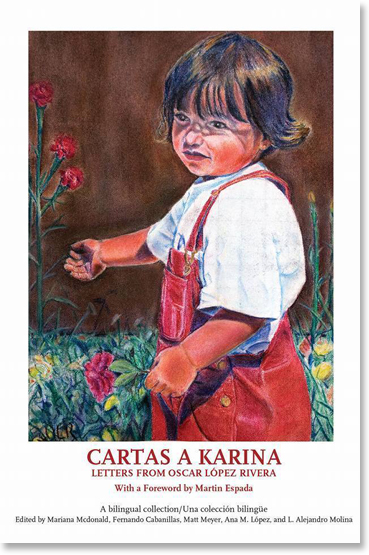

Cartas a Karina, letters written to his granddaughter Karina; cover painting by OLR.

|

|

|

|

Children march for Oscar’s freedom as part of the 2nd Caminata, 2015.

|

|

|

|

NYC's 35 Women for Oscar demonstrate for his freedom.

|

|

|

|

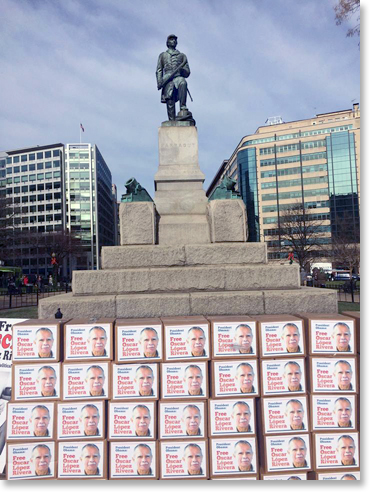

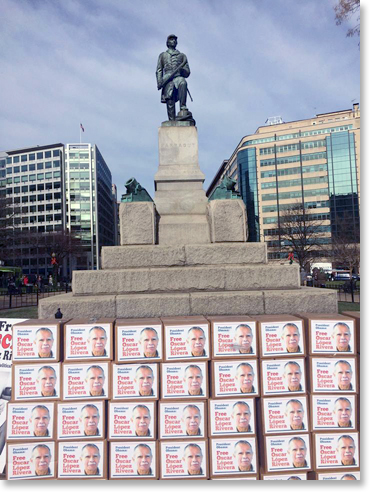

Over 100,000 petitions for Lopez Rivera’s release delivered to White House 1/11/17.

|

|

|

|

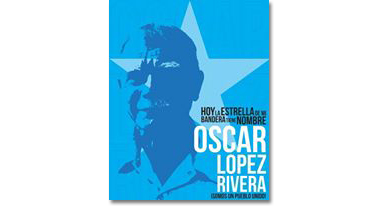

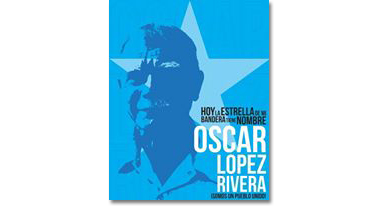

López Rivera, home at last. "Today the star of my flag has the name Oscar López Rivera."

|

|

|

|

|

Quick Links:

The afternoon of January 17, supporters of Oscar López Rivera were abuzz with texts and calls and emails, as word began to leak out that Barack Obama commuted the Puerto Rican independence fighter’s sentence. By late afternoon it was confirmed that Obama had commuted the 70-year sentence, with López Rivera’s unconditional release to take place May 17.

Immense joy and excitement were palpable, the fruits of the long fight to release López Rivera, imprisoned since May 1981 for seditious conspiracy, the thought crime of wanting to make Puerto Rico free from colonial domination. Oscar López Rivera has become a worldwide symbol of the fight for Puerto Rican self-determination and for human rights, peace, and the health of the planet. Despite 12 years in solitary confinement, he has maintained his political vision, integrity, and humanity throughout nearly 36 years of dehumanizing imprisonment. He is widely regarded as the Mandela of Puerto Rico and the 21st century.

The significance of the commutation, and the immense popular victory it represents, cannot be overstated for López Rivera, his family, friends and compañer@s. His only daughter, Clarisa López Ramos, has spent the past three and a half decades visiting her father in US gulags, making some 150 trips from Puerto Rico in the past 18 years. Clarisa’s daughter, López Rivera’s granddaughter Karina Valentín, has only known her grandfather in prison, where she and her mother have suffered extreme restrictions during visits. After the commutation, from prison López Rivera wrote “it happened the day before my precious Clarisa's 46 birthday ... Both of us were extremely happy Obama decided to make his decision on the 17th of January - a date both of us will never forget.”

Who is Oscar Lopez Rivera?

Oscar López Rivera is a working class Puerto Rican patriot born in San Sebastian, Puerto Rico in 1943. He is a Bronze-star decorated Vietnam Veteran, a father, grandfather, brother, uncle, and friend. He has been a political prisoner for over 35 years in the U.S. prison-industrial complex, incarcerated at five different U.S. Bureau of Prisons sites. The charge against him, seditious conspiracy, is the same kind of charge railed at Gandhi and Mandela; it is one based solely on his political beliefs. He was never linked to a criminal action that injured or killed anyone. He is one of the longest-held political prisoners on the planet, and his is one of the longest political imprisonments in documented human history.

López Rivera is an independence fighter and community leader shaped by a profound love of his homeland, by the indignities of foreign domination and forced emigration, by his extended family, and by the richness of Puerto Rican culture. He is also an accomplished and respected painter, a vocation he began while in solitary confinement for 12 years in a cramped monochromatic cell that threatened his very ability to see colors. His work has been exhibited in three countries, and some of his paintings have been famous gifts, such as his luminescent portrait of His Holiness given to the Pope during the fall 2015 visit to New York City. (See: Brushstrokes for Liberation: The Art of Oscar López Rivera)

López Rivera is also a prolific writer; his book Between Torture and Resistance was published in 2013, and the bilingual collection of his letters to his granddaughter, Cartas a Karina, was published last fall.

The Fight to Free Puerto Rican Political Prisoners

López Rivera was imprisoned for being a leader of the F.A.L.N., a Puerto Rican independence group that fought for Puerto Rican sovereignty and was associated with bombings in the 1970s. While López Rivera was never linked to injuries or deaths from those acts, he was convicted of seditious conspiracy and transporting firearms and explosives, and was sentenced in 1981 to 55 years in prison. A putative escape attempt, fabricated by prison officials, added 15 years to his sentence.

López Rivera is one of a number of Puerto Rican political prisoners convicted of seditious conspiracy in the eighties. An international movement led by supporters in Puerto Rico and the diaspora, as well as international allies, pressed for their release on human rights grounds, noting their sentences were vastly disproportionate. When then-President Clinton offered the prisoners a pardon in 1999, it did not include two of López Rivera’s comrades, and he chose to decline it. Those prisoners, Haydée Beltrán and Carlos Alberto Torres, were released in 2009 and 2010, leaving López Rivera the last remaining Puerto Rican political prisoner in U.S. prisons.

Intensification of the campaign for López Rivera’s release

IWhen his 2011 parole bid was denied, López Rivera’s supporters began to mount a massive international campaign for his release, one which consistently demonstrated creativity and determination and was characterized by ever-increasing unity.

In 2012 an impressive array of Noble Peace Prize laureates joined the call to President Obama for his release. They included Coretta Scott King, President Jimmy Carter, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Rigoberta Menchu, and Mairead Corrigan Maguire. They were joined by an international coalition of human rights, religious, labor, and business leaders, including the United Council of Churches of Christ, United Methodist Church, Baptist Peace Fellowship, Episcopal Church of Puerto Rico, and the Catholic Archbishop of San Juan.

On the island and in the diaspora, creative and attention-grabbing activities to raise awareness about López Rivera began to grow exponentially. In spring 2013, for example, in Puerto Rico's four largest cities (San Juan, Ponce, Mayagüez, and Arecibo), celebrities, artists, religious leaders, elected officials and community members "went to prison” in mock 6’ x 9’ cells in solidarity with Oscar López Rivera.

In 2014 the first of two island-wide Caminatas was organized, with supporters walking from town to town to demonstrate and build support for López Rivera’s release. The first Caminata covered 33 cities in 33 days, walking through mountainous regions of Puerto Rico in a "freedom walk for Oscar." Nineteen cities passed resolutions in favor of Oscar’s release; several had already passed such resolutions.

In 2013 women began to take a leading and visible role in the movement to bring López Rivera home. 32 Mujeres X Oscar was launched in Puerto Rico in 2013, with 32 women meeting at the Puente Dos Hermanos, San Juan, a popular tourist area, for 32 minutes the last Sunday of each month to demand López Rivera’s release. In 2014, New York women followed island women’s lead and began 33 Mujeres NYC X Oscar, protesting the last Sunday each month to bring awareness of the campaign for Oscar’s release. In 2015 34 Mujeres Chicago X Oscar and 34 Mujeres Boston X Oscar were launched. The monthly demonstrations have served as a vivid and vocal reminder of López Rivera’s unjust imprisonment and the determination to win his freedom.

International calls for López Rivera’s unconditional release continued to grow. Extensive support was garnered from leading political figures, including José “Pepe” Mujica of Uruguay, who wrote to Obama urging López Rivera’s release. President Maduro of Venezuela in 2014 addressed the United Nations and demanded President Obama grant clemency to Oscar; he later declared Oscar “the Mandela of Latin America.” In November 2014 Puerto Rico’s governor Alejandro Garcia Padilla visited Oscar López Rivera in federal prison in Terre Haute, Indiana, the first time in history a Puerto Rican governor visited a political prisoner in an official capacity. And in January 2015 in Costa Rica, at the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) meeting, Nicaraguan president Daniel Ortega ceded his seat to independence leader Rubén Berríos, who called for Oscar’s release.

On May 30, 2015 a massive march in New York City raised the demand for López Rivera’s freedom under the banner of “One Voice for Oscar.” Over 5,000 people took to the streets in a unified cry for his immediate and unconditional release.

The clock ticks as end of Obama’s tenure approaches

As the end of Barack Obama’s tenure in office neared, the movement to free López Rivera intensified. An October rally brought thousands to DC to protest directly across from the White House. An ongoing petition drive was consolidated, amassing over 100,000 signed petitions calling for López Rivera’s freedom. And in November an online petition was launched on the Obama administration’s “We the People” website, a petition that would only be “heard” if at least 100,000 petitions were signed. In an intensive effort, over 108,000 signatures were collected in just 30 days, heartening López Rivera’s supporters and giving them hope that Obama would “do the right thing.”

The campaign for López Rivera’s release held a final rally in Washington DC on January 11, just days before Obama would leave office. The rally marched to the White House to deliver a parade of 35 boxes of petitions. In the weeks before Obama’s final day in office, President Jimmy Carter wrote to Obama asking that he release López Rivera, and Pope Francis was reported to use diplomatic channels to the same end. At the January 11 event a moving letter was read from Nobel Laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu. A great sense of yearning surrounded the ardent protestors, who in less than a week would learn their hopes had been realized.

February 9, 2017 -- En Casa / At Home at Last!

On February 9, cyberspace was abuzz once more. When López Rivera learned of his commutation, he also learned of the possibility of serving the final four months of his sentence in Puerto Rico at a halfway prison facility. As that possibility became a reality, it became more and more shrouded in secrecy, such that López Rivera himself only learned details of his transfer to Puerto Rico in the last moments. What had been negotiated and agreed upon was a transfer in which López Rivera would be required to keep a “low profile,” escorted by elected officials Congressperson Luis Gutiérrez (Democratic Party-Illinois), New York City Council president Melissa Mark-Viverito, and San Juan mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz, along with López Rivera’s lawyer Jan Susler, his daughter Clarisa, and brother José.

The afternoon of Thursday February 9, 2017, Oscar López Rivera returned to Puerto Rico for the first time in 40 years. There was great joy in learning he would not be held in a halfway prison facility, but instead would be able to live with his daughter at her home, under “house arrest” wearing an electronic ankle bracelet. While still in the custody of US prisons and required to adhere to specific restrictions, López Rivera was at last "en casa” -- at home, the goal so many had fought for many years. Tears of joy streamed around the world that day, and the jubilation of López Rivera and his loved ones was unparalleled.

The victorious nature of the events of January 17 and February 9 continues to be celebrated, lauded, and appreciated, as a massive, multifaceted welcome/celebration is being planned in Puerto Rico for May 17, when Oscar López Rivera will be unconditionally released to the eager embrace of his people.

"A great victory has been achieved by Puerto Rican people in PR and the diaspora, and by freedom and justice loving people from many parts of our planet ..." wrote López Rivera from prison to a friend on February 4. "i would like to see it being used to galvanize our people in order to start a viable process of decolonization. We must decolonize ourselves in order to decolonize our nation. We can build on the unity that has been achieved by the campaign in Puerto Rico and in the diaspora. This has been a campaign that reflects the creativity of our people, the love for freedom and justice that is in their hearts, and that we have the potential and the human and natural resources to transform our nation into an edenic garden.”

Also see:

Published in In Motion Magazine February 27, 2017

|