|

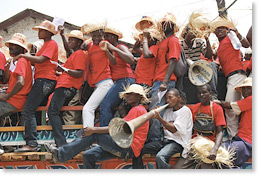

Haitian Peasants March Against Monsanto Company

for Food and Seed Sovereignty by La Vía Campesina Hinche, Haiti

The poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, Haiti shares the Caribbean island of Hispaniola with the Dominican Republic. About 65 percent of Haiti’s population lives in rural areas and are subsistence farmers. On January 12, 2010, a devastating earthquake leveled Haiti's capital city Port au Prince, and 800,000 urban refugees migrated to rural areas. According to Chavannes Jean-Baptiste, coordinator of the Papaye Peasant Movement (MPP) and a member of La Via Campesina’s international coordinating committee, "there is presently a shortage of seed in Haiti because many rural families used their maizeseed to feed refugees." With sales of $11.7 billion in 2009, US-based transnational corporation (TNC) Monsanto Company is the world’s largest seed company, controlling one-fifth of the global proprietary seed market and 90 percent of seed patents from agricultural biotechnology. In May Monsanto announced that it had delivered 60 tons of hybrid seed maizeand vegetables to Haiti, and over 400 tons of its seed (worth $4 million) will be delivered during 2010 to 10,000 farmers. The TNC United Parcel Service is providing transport logistics, While Winner, a $127 million project funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and focused on "agricultural intensification", is distributing the seed. (1) According to Monsanto, the decision to donate seed to Haiti was decided at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland: "CEO Hugh Grant and Executive Vice President Jerry Steiner attended the event and had conversations with attendees about what could be done to help Haiti." (2) It is unclear whether any Haitians were included in the conversations in Davos. Some have charged that the Monsanto representative in Haiti is Jean-Robert Estimé, who served as foreign minister during the brutal 29-year Duvalier family dictatorship. (3) While Monsanto vehemently denies this claim, (4) Estimé is included in an email exchange about the donation between Elizabeth Vancil, Director of Global Development Partnerships at Monsanto and Emmanuel Prophete, a Haitian agronomist working for the Minister of Agriculture. (5) The domain for Estimé’s email address is for Winner (www.winner.ht). (6) Many Haitians consider Monsanto's seed donation to be part of a broader strategy of US economic and political imperialism. "The Haitian government is using the earthquake to sell the country to the multinationals," stated Jean-Baptiste. Vancil stated that opening up Haitian markets to Monsanto’s products "would be good." (7) Monsanto is emphasizing that the donated seed is hybrid and not genetically-modified (GM). (8) However, hybrid seed will not increase Haitian farmers’ food sovereignty or self-reliance; Monsanto acknowledges that they will be unable to save seed to plant in the future, (9) and that although the seed is being provided free of charge, farmers will pay for it. "Providing an outright donation of seed would undercut one of the basic pieces of Haiti's agricultural and economic infrastructure," says Monsanto, (10) which is donating the seed to the government to sell to farmers. Winner is distributing the seed through farmer association stores, which will use the revenue to reinvest in other inputs, and help "farmers decide whether to use additional inputs (including fertilizer and herbicides) and how to handle next year’s planting season." (11) Haiti's agricultural sector has already been decimated by US interference. In 1991, Jean Bertrande Aristide, Haiti's first democratically-elected president, was removed in a US-supported military coup. As a condition for his return, the US, IMF and World Bank required that Aristide open up Haiti to free trade. Tariffs on rice (Haiti's staple grain) were reduced from 35% to 3%, government funding was diverted away from agricultural development to the nation's foreign debt, and subsidized rice from Arkansas (it was the Clinton administration) flooded the Haitian market. Haitian rice farmers were decimated, (12) and today almost all of the rice consumed in Haiti is imported. Sacks marked "US Rice" are everywhere in the markets and neighborhood stores, on peoples' heads and the backs of mules. The US is now undermining Haiti’s food system from the ground. A letter from the Haitian Minister of Agriculture to Monsanto implies that GM seed may have been offered in addition to hybrid. "In the absence of a law regulating the use of genetically-modified organisms (GMO) in Haiti, I am not at liberty to authorize the use of Roundup Ready seed or any other GMO material," stated Juanas Gue, Haitian Minister of Agriculture, in a letter to Monsanto, (13) which has already proven the length it will go to open new markets in developing countries for its GM seed and toxic chemicals. In 2005, Monsanto was found guilty by the US government of bribing high-level Indonesian officials to legalize GM cotton. Evidence indicates that in Brazil in 2004, Monsanto sold a farm to a senator for one-third of its value in exchange for his work to legalize glyphosate, the world’s most widely used herbicide (sold by the corporation as Roundup). (14) According to Paulo Almeida, 31, a member of the Brazilian Movement of Landless Rural Workers who has been in Haiti since 2009 on a solidarity brigade organized by Via Campesina-Brasil, Monsanto also encouraged Brazilian farmers to illegally plant Roundup Ready soybeans. "They want to implant the technological package of the Green Revolution, which isn’t possible here in Haiti. There is no way to survive with monoculture here." The hybrid seed maize donated by Monsanto was treated with the fungicide Maxim XO, and the calypso tomato seed were treated with thiram, a chemical so toxic that the US government requires agricultural workers to wear protective clothing when handling seed treated with the fungicide. Monsanto's communications to the Ministry of Agriculture contains no explanation of the danger of these chemicals, or any offer of special clothing or training for Haitian farmers.(15) Development of industrial agriculture in Haiti is related to plans to develop an export-oriented agrofuels industry in the country. In 2007 USAID published a report on the ‘prospects for solid and liquid biofuels in Haiti', (16) while the Inter-American Development Bank’s Haiti strategy document for 2007-2011 states that removing "obstacles to export of agricultural products are a top priority," and that "biofuel promotion is being explored specifically." (17) The Obama administration has a hypocritical and inconsistent policy on Monsanto and GM crops. When the Obamas moved into the White House they planted an organic garden, and one can only assume they did not plant GM or hybrid seed. In the US Monsanto monopolizes 60 percent of the entire seed maizemarket and 80 percent of the GM seed maizemarket. In March the administration convened public anti-trust hearings on competitiveness in the US seed market, and has yet to publish its conclusions. Yet the Obama administration is strongly promoting the interests of US agricultural biotechnology TNCs abroad. At the Biotechnology Industry Organization's annual convention in May, Jose Fernandez, assistant secretary for the Bureau of Economic, Energy and Business Affairs, stated that the US State Department (which controls USAID) will aggressively confront critics of agricultural biotechnology. (18) Meanwhile, the US Supreme Court is presently deliberating Monsanto Co. vs Geertson Seed Farms, a case about the ecological and economic effects of genetic contamination of organic seed from GM pollen. A favorable decision for Monsanto will lead to the widespread contamination of organic alfalfa, which will destroy the organic milk industry in the US. Though Monsanto's GM pollen has been contaminating Mexican corn for a decade, the corporation recently received license from the country’s government to conduct open field trials of GM maize in four states. Mexico is the cradle of maize, with thousands of native varieties. Contamination of Haitian maize with pollen from Monsanto's hybrid corn will also occur, and could render the Haitian varieties unusable for saving and replanting, forcing farmers to become dependent upon the corporation. "The entrance of Monsanto into Haiti will spell the disappearance of the peasants," said Doudou Pierre Festil, a member of the Peasant Movement of the Congress of Papaye and coordinator for the National Haitian Network for Food Sovereignty and Security. "If Monsanto’s seed come into Haiti, the seed of the peasants will disappear. Monsanto’s seed will create problems of health and for the environment. Thus it is necessary for us to struggle against this project of death to do away with the peasants." "If the US government truly wants to help Haiti, it would help the Haitians to build food sovereignty and sustainable agriculture, based on their own native seed and access to land and credit. That is the way to help Haiti," says Dena Hoff, a diversified organic farmer in Montana and member of Via Campesina’s international coordinating committee. The United Nations estimates that 75 percent of the world's plant genetic diversity has been lost as farmers have abandoned their local seed for genetically-uniform varieties offered by TNCs, and as GM and hybrid seed have contaminated native varieties. Genetic homogeneity increases farmers' vulnerability to sudden changes in climate and the appearance of new pests and diseases, while seed agrobiodiversity, adapted to different microclimates, altitudes and soils, is fundamental for adapting to climate change. Critics of Monsanto's donation argue that the best way to ensure enough seed for Haiti is through the collection, conservation and propagation of local, native varieties in community seed banks. Haiti's native seed varieties have developed and adapted to the different regions of Haiti over generations, in tandem with its people. Saving and replanting seed strengthens crops' genetic plasticity, e.g. their capacity to adapt rapidly over generations to changing growing conditions, and also increases agrobiodiversity. Island nations are particulalry vulnerable to climate change. If the US does not get its policy for Haiti right this time, there will not be another chance. Given the extent of food insecurity and environmental degradation in Haiti, the country must adopt a policy for food sovereignty in order for its people and biodiversity to survive. Ninety-eight percent of Haiti's original tropical forest cover has been lost, there is widespread soil erosion, and desertification is increasing. Haiti cannot sustain further ecological destruction from the imposition of industrial agriculture. Alternatively, if the Obama administration supports a policy of food sovereignty in Haiti, the country could construct a model food system that could feed all Haitians healthy food, increase biodiversity and ecological resilience, and contribute to local, sustainable economic development. Recent research by agroecologists at the University of Michigan shows that sustainable, small-scale farming is more efficient at conserving and increasing biodiversity and forests than industrial agriculture.(19) In order to implement a policy for food sovereignty, Haiti must develop without Monsanto’s seed. Fortunately, Haitian peasants have a long history of resistance and struggle. Haiti was the first colony in the Western Hemisphere to have a successful slave revolt that resulted in an independent nation in 1804. Haiti became a global pariah to the emerging global powers, especially the US. "We defend peasant agriculture, we defend food sovereignty, and we defend the environment of Haiti until our last drop of blood," states the Final Declaration of the march against Monsanto. "We commit to unite our forces to change this anti-peasant, anti-national state. We want to construct another kind of state, a state that defends peasant agriculture, a state that assists the rural men and women in the protection of the environment, and the conservation of soil and forest." (20) Speaking from a stage in Charlemagne Péralte plaza, named for the Hinche-born leader of an armed movement against the 1915-1934 US occupation of Haiti, Jean-Baptise symbolically set Monsanto seed on fire, while others began to distribute packets of native seed maize to the cheering crowd. "We have to fight for our local seed," Jean-Baptiste told them. "We have to defend our food sovereignty." (21) Published in In Motion Magazine June 29, 2010 La Via Campesina -- An "international movement of peasants, small- and medium-sized producers, landless, rural women, indigenous people, rural youth and agricultural workers. ... We are an autonomous, pluralist and multicultural movement, independent of any political, economic, or other type of affiliation. Our 148 members are from 69 countries from Asia, Africa, urope, and the Americas." Footnotes (footnotes open in a separate browser window for easy reference) Also see:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2018 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |