|

The Corporate Grab for Control of the Hog Industry

and How Citizens Are Fighting Back by Patty Cantrell, Rhonda Perry & Paul Sturtz Columbia, Missouri

This article is taken from the Missouri Rural Crisis Center publication "Hog Wars: The Corporate Grab for Control of the Hog Industry and How Citizens are Fighting Back" Part 1 - Missouri was corporate agriculture's dream state

By 1995, however, thousands of Missourians had taken it upon themselves to overturn their state's welcome mat. Frustrated by weak laws and insider politics, they found themselves combing through real estate records, speaking at public rallies and calling strategy sessions. By the end of the 1996 legislative session, this growing grassroots coalition of farmers, environmentalists, consumers and businesses succeeded in slapping the state's Boss Hogs out of their factory farm bliss. With a final 32-1 Senate vote on vital community protections against CAFOs, this network of ordinary-citizens-turned-overtime-activists put pork powermongers on notice. "I'm satisfied that the big corporations got the message that things could get worse for them if they don't shape up," says Gene Andersen, whose farm is bordered on three sides by Murphy Family Farms' operations. Mega livestock producers and friends "came in thinking they could paint a pretty picture, spend a little money here and there and do what they pleased. They found it wasn't that way at all." The battle, however, was not easy and is not over. Andersen and other members of 14 community groups who came together to form Missouri Rural Crisis Center's ag policy task force know that big pork's public relations machine is already spreading its hogwash in other states. After apparently slowing its expansion in southwest Missouri, for example, Murphy Family Farms stepped up its courtship of rural communities in Kansas and Illinois. "We can't afford to let down our guard," says Sally Radmacher of Platte County Concerned Citizens. "This is just kind of creeping across the country. I don't think these things belong anywhere in the world. It's not a good way to farm. It's bad for the environment. It's bad for the animals, and in the long run it's bad for the farmers who contract with these corporations."CAFOs continue to creep across state lines and from poultry and pork into the beef and dairy industries. They are powered by persistent myths that corporate public relations specialists use to convince people that factories are like families, that mass production makes better meat and profits and that the hungry world should be thankful for high-tech methods that keep animals alive and growing in unspeakable conditions. Countering these assumptions and changing local, state and national opinions is a big job given the hold these myths have on policy makers. But Missourians launched a new political consciousness by getting together to organize their arguments and focus their growing diversity and strength on a common goal. How Missourians dispelled the myths, survived character assassinations and built an even stronger base for securing the future of family farming is a harrowing story. It comes complete with legislators who feed at the corporate trough and with last-minute corrections of sly changes in legislative language. It is presented here as a study of real-life grassroots challenges and as proof that a new, diverse political base can mount a viable challenge to cruel and unusual development.

MRCC members were among the first to speak out against PSF's plans to integrate swine production from piglet to pork chop. They warned that the "Tyson model" PSF professed would bring the same environmental and economic degradation that Tyson, Perdue and Holly Farms brought with the poultry industry. History shows that vertical integration in the poultry industry has eliminated independent markets and farmers; starved local businesses of sales to formerly independent farmers who are now just contract employees; unraveled communities that were knit together by interlocking relationships; fouled the environment with animal factory stench and sludge; and lowered the quality of consumer products through the exclusive use of mass production facilities. The smell of money, however, was stronger than this evidence in 1989, when the governor welcomed PSF to Missouri on the steps of the State Capitol. At the time, PSF was only talking a few thousand hogs, says MRCC executive director Roger Allison. Within two years, PSF was up to 25,000 sows and planning to build its own $8 million feed mill. By 1996, PSF had 105,000 sows and produced more than 2.5 million hogs each year. It's easy to understand why the pork producers association liked the outcome. The commodity group's budget comes from a percentage of the price of each hog sold in the state (about 60 cents a hog). CAFOs mean more hogs and more money for the association. The others involved in granting PSF safe haven liked the appearance of job creation. A multi-million-dollar operation would require workers to keep the pork pumping. PSF was touted as an economic savior for a struggling area of northern Missouri. The fact that it would also displace existing farmers and their local purchases was not part of the equation. It was not easy for residents and their elected officials to see the long-term, debilitating economic and environmental effects. The hoopla died down once PSF started construction. PSF revived interest through its gluttonous land-grabbing expansion through northern Missouri. MRCC's members, including Terry Spence, who lives within eye-, ear- and nostril-shot of PSF lagoons, couldn't overlook the giant in their midst. "This is the farm where I was born and raised," he says. "I purchased it from my parents in 1967 and worked three jobs sometimes to pay for it. To just pack up and leave is not right. I don't think anybody should be run from their home. Us and our grandparents, everybody's labored hard for lifetimes to be good stewards and stay on the land." Spence and his Lincoln Township neighbors were watching the 2,000-pound gorilla come to life behind PSF's good-old-boy propaganda. By the close of 1993, they knew they needed to take strong action because the state legislature passed a last-minute amendment exempting from Missouri's corporate farming laws the three counties where PSF operated. The township passed planning and zoning regulations requiring CAFOs to keep a mile-wide buffer between facilities and residences and to secure bonding for sewage lagoon cleanup. PSF promptly sued the tiny township for $7.9 million. By raising the stakes in this way, however, PSF also did opponents a favor. Its arrogant challenge of local democracy gave the public a perfect opportunity to understand the larger threat. "It was the catalyst that launched the national Campaign for Family Farms and the Environment," Allison says. And it was this national spotlight on the methods and madness of mega pork that made the 1996 session of Missouri's General Assembly so much different than the year before. "The 1995 session was the first shot across the bow to let them know we were organizing," says Rhonda Perry of MRCC. "We were fairly naive in some respects about who our friends were or should have been." The group's members had drafted legislation based on 12 "Good Neighbor" policy points (see sidebar, p. 17) and had started the agriculture policy task force to organize across the state. But they didn't have the clout to make a dent in a power structure that was busy asking the wrong questions and answering to the wrong people. "We left that place and went to work on a new strategy of approaching them from a position of power," Perry says. Lincoln Township's struggle was the prime place to focus the organizing efforts of Missouri groups and others fighting factory farms across the nation. "PSF was the flagship of the industry and all the other companies were watching its lead," Perry says. "So we targeted PSF, this David and Goliath story, to talk about the industry as a whole."

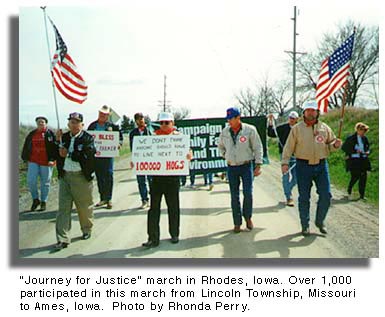

The Campaign drove that universal point home by following the rally with a six-day march from Lincoln Township to Ames, Iowa, where President Clinton and U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Dan Glickman were scheduled to appear. The national Campaign for Family Farms and the Environment carried the "family farms, not factory farms'' message through rural towns and into Ames, where they received word that Glickman would meet with them in June in Washington, D.C. The Campaign demanded immediate action on government policies that keep animal factories expanding. At the top of the list: Enforce the anti-trust Packers & Stockyards Act; stop factory farm credit that was meant for family farmers; halt taxpayer-funded research that benefits only CAFOs; and strengthen lax environmental laws. |

| Published in In Motion Magazine - December 6, 2001 |

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2020 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

In 1992, Missouri was corporate agriculture's dream state. The legislature had just broken its own anti-corporate farming laws by giving one factory hog operation the unprecedented ability to go to Wall Street for junk bond financing of mega expansions. The company, Premium Standard Farms (PSF), had already been testing the shallowness of Missouri's enviromental laws. PSF showed how it could sweet-talk local and state leaders, build huge concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) and get by with saying that concentration of thousands of animals and millions of gallons of untreated sewage didn't stink. Before long, Tyson Farms, Continental Grain, and the nation's largest hog producer, Murphy Family Farms, followed PSF into Missouri. They set up their own hog factory complexes along the same slick lines: no notification for neighbors, no need to meet the same standards as similar size industry and no regard for their destruction of family farmers, property values and quality of life.

In 1992, Missouri was corporate agriculture's dream state. The legislature had just broken its own anti-corporate farming laws by giving one factory hog operation the unprecedented ability to go to Wall Street for junk bond financing of mega expansions. The company, Premium Standard Farms (PSF), had already been testing the shallowness of Missouri's enviromental laws. PSF showed how it could sweet-talk local and state leaders, build huge concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) and get by with saying that concentration of thousands of animals and millions of gallons of untreated sewage didn't stink. Before long, Tyson Farms, Continental Grain, and the nation's largest hog producer, Murphy Family Farms, followed PSF into Missouri. They set up their own hog factory complexes along the same slick lines: no notification for neighbors, no need to meet the same standards as similar size industry and no regard for their destruction of family farmers, property values and quality of life. The best place to start this victory tale is in the beginning, with failure. Two instances in particular showed the Missouri Rural Crisis Center's members what they were up against and how to win. The first was in 1989 when MRCC opposed Premium Standard Farms' squeal-to-meal vertical integration plans. The second was in the 1995 legislative session when MRCC members still operated with the belief that truth was strong enough and that politicians kept their promises.

The best place to start this victory tale is in the beginning, with failure. Two instances in particular showed the Missouri Rural Crisis Center's members what they were up against and how to win. The first was in 1989 when MRCC opposed Premium Standard Farms' squeal-to-meal vertical integration plans. The second was in the 1995 legislative session when MRCC members still operated with the belief that truth was strong enough and that politicians kept their promises. Help came just as quickly as MRCC and fellow anti-CAFO groups put out the call. Organizations from across the Midwest including Land Stewardship Project, Clean Water Network and Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement, came together to form the national campaign. One of the first calls went out to Farm Aid, longtime supporters of MRCC. Lincoln Township residents followed up with letters to Farm Aid and Willie Nelson, who promised to lend support. A rally was planned in Lincoln Township to draw national attention to heavy-handed corporate bullying of rural communities. Then PSF went into full gear. It got the mayor, the head of the Rural Electric Association, the bankers, legislators and real estate people all involved in trying to convince Nelson not to come to Lincoln Township. The family farm side won that battle. The rally on April 1, 1995, was a huge success with more than 3,000 people from across the country and more than 22 speakers, including representatives from the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, the United Auto Workers, the National Farmers Union and the Humane Farming Association. "Missouri became nationally known as a fightback state," Allison says. And the national media was introduced to the factory farm issue as the deciding difference "between a good agricultural system and a bad agricultural system," he says. Corporate agriculture's threat to democracy, the environment, rural economies and consumer's choice became an issue for America, not just factory farm neighbors.

Help came just as quickly as MRCC and fellow anti-CAFO groups put out the call. Organizations from across the Midwest including Land Stewardship Project, Clean Water Network and Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement, came together to form the national campaign. One of the first calls went out to Farm Aid, longtime supporters of MRCC. Lincoln Township residents followed up with letters to Farm Aid and Willie Nelson, who promised to lend support. A rally was planned in Lincoln Township to draw national attention to heavy-handed corporate bullying of rural communities. Then PSF went into full gear. It got the mayor, the head of the Rural Electric Association, the bankers, legislators and real estate people all involved in trying to convince Nelson not to come to Lincoln Township. The family farm side won that battle. The rally on April 1, 1995, was a huge success with more than 3,000 people from across the country and more than 22 speakers, including representatives from the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, the United Auto Workers, the National Farmers Union and the Humane Farming Association. "Missouri became nationally known as a fightback state," Allison says. And the national media was introduced to the factory farm issue as the deciding difference "between a good agricultural system and a bad agricultural system," he says. Corporate agriculture's threat to democracy, the environment, rural economies and consumer's choice became an issue for America, not just factory farm neighbors.