|

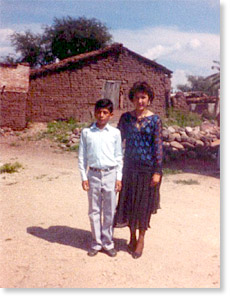

No Immigration Without Emigration:

Consequences For The Countries Left Behind Seattle, Washington

Certainly you’ve read about the effects the recent and continuing wave of immigration is having -- or is thought to be having -- upon the United States. Of course, there is much impassioned debate whether the effects are good or bad. Clearly, arguments to support both sides can be made. Nevertheless, a large influx of laborers willing to work for any wage above $2 an hour arguably creates a wide range of consequences for U.S.-born workers. Some argue for the benefits of increased cultural diversity; others emphasize the burdens undocumented aliens place upon the social services of American towns, cities, and states. Some argue that the immigration of low-skilled, primarily Latino workers is valuable because it provides employers with a ready supply of labor to do the work that Americans consider to be undesirable and under-compensated; still others argue that the addition of such immigrants to the workforce will ultimately drive down the level of wages even in more desirable work situations. In any case, if you still find yourself undecided, there are plenty of talk shows, political debates, and newspaper articles dedicated to the analysis on both sides of the issue. Interestingly enough, throughout all this debate, little -- if anything -- is said about the effect on the Latin American countries people are leaving to come to the United States. Take Mexico, for example. When my father left a small village in Jalisco in 1950, he was 20 years old and the oldest of six children. As the oldest son, he was also set to inherit the ejido (a communally owned Mexican farm) passed on to his father as a result of the Mexican Revolution in the 1900s. Instead, he had heard that he could make more money working in the fields for other people than harvesting sugarcane and corn from his own land. So, my father and two of his friends showed up at a gathering in Guadalajara. This gathering was set up at the request of U.S. farmers looking for braceros or manual laborers. Wages were minimum, but room and board were included, as well as transportation to and from the border. My father was chosen and he was told to report to the border town of Nogales. His first work assignment was in Stockton, California. He worked at this assignment for a few years and eventually earned the right to legal permanent-residency status. That was all in the years following World War II, when the United States needed hard-working men to replace those who had lost their lives in the war. However, times in the United States are different now. Even though the United States is at war, there is no shortage of manual labor. Now, landowners -- both farmers and ranchers -- no longer need to cross the border to recruit workers to come here. Those workers who were wooed in the past with promises of room, board, and decent wages no longer need to be convinced. Today, workers freely come to the United States to work, crossing the border, leaving their families, and risking their lives. Eighteen years ago, I spent a summer in my father’s village in Jalisco. I was in college then, and I have always had a strong and fond connection to the place. We used to spend our summers there when we were kids. I remember those days as if it were yesterday. The days seemed endless. Mornings began at around 5:30 a.m. It was hard to know exactly what time it was, because no one had a watch or a clock. Early in the morning, I would accompany my cousin to the mill to grind our corn into flour for tortillas. We would cook the tortillas over an open fireplace, which was built into the kitchen wall. That summer, I spent Sundays watching soccer games at the village soccer field. Each Sunday, a different neighboring team would challenge the local team. Sometimes the team would have to travel for the game and the whole village would travel with them. Talk about team spirit! During the week, my cousin and I would saddle our horses and ride up to the mountains and pick oranges. On Saturdays, my cousins and I would dress up and go to dances at the neighboring villages. There was always a wedding, a quinceañera, or a baptism. There was at least one dance every Saturday. Once, my cousin and I went to four dances in one weekend! There were also horse races on the weekends. Sundays also meant that we would go into the city in the evening and hang out at the plaza to cenar, or have supper. We would buy fresh fruit smoothies and eat snacks. But the most fun was strolling around the plaza. The men walked counterclockwise and the women clockwise. The plaza would get packed with young people moving in circles. Occasionally, a man would hold out a flower to us as we passed to show his interest. If we were interested, we would take the flower. Then eventually, at some point there would be an invitation to leave the circle and move to one of the many surrounding benches to talk. That summer I celebrated my 21st birthday there. I was awakened that morning by a birthday serenata. The serenata group was a few guys from the village and they brought rocks and sticks. Endearing. I left at the end of the summer, not realizing that I would not return for 18 years. Even if I had realized that I wouldn’t be returning for such a long time, I would never have guessed how drastically life in Mexico would have changed by the time I did eventually return. Finally, I returned in October 2005. I was so excited to visit, as if I was returning for a homecoming. However, everything had changed. The first sign that the village was not the same was waking up in the morning to the sound of trucks driving on the cobblestone streets. There had been very few cars when I had last been there. Now SUVs ruled the roads. There were practically no horses left. The sugarcane fields were gone. The corn fields were gone. I was there for 10 days and did not see anyone make tortillas. The sound of the mill was replaced by the trucks that came into the village from the big city of Guadalajara to sell tortillas and the dough for tortillas. The soccer field was overgrown with weeds. In fact, no one could remember when the last soccer game was played. The place where the horse races were held was no longer noticeable. The plaza was empty on Sundays, except for a few men standing around and an older couple sitting on one of the benches. It took me a while before I noticed there were no young adult men. There were teenagers and older men, but practically no men between 20 and 50. The sugarcane fields and the corn fields had been replaced with agave plants (from which tequila is distilled). I was told that agave required less manpower and was harvested every few years instead of every year. There were women of all ages and there were young children, but it seemed that fatherless families were more prevalent than not. I visited a few surrounding villages and found the same -- no young adult men. But, strangely enough, the houses were fancier, thanks to the materials shipped in from the United States. The village had a brand-new plaza and a brand-new church. There was a new kindergarten/daycare center, although the elementary school was the same. Almost all the homes had satellite television, a Dodge Ram truck, coffee makers, and even gas stoves. No more open fires. Even the traditional molcajete had been replaced by the convenient blender. The village certainly prospered from having its labor force working for dollars in the United States. But the negative consequences of migration were evident in its daily life. The loss of the social customs of dating -- a change culturally devastating in and of itself -- was emblematic of the destruction of community and traditions and their replacement by the depersonalizing accumulation of commodities. A change to last forever. It became obvious to me that the issue of immigration is not confined to the topic of cheap labor in the United States. Mexico and other Latin American countries are deeply affected by the loss of their young adult men. The absence of young adult men has created a damaging hole in the social infrastructure of Mexico. Mexico cannot possibly protect itself against a foreign invasion, whether military or cultural, when so many of its young able-bodied men are living and working in the United States. Nor can Mexico successfully push itself into a prominent position in world markets without their help. Worst of all, Mexico is on the verge of losing its culture -- a way must be found to keep its men at home. In its willing sacrifice of the most productive years in the lives of its men in the American labor market, Mexico has been heedlessly complicit in the uprooting of its cultural heritage, its characteristic ways of life, and its traditional values. On the other hand, the United States has accepted the sacrificial gift, has benefited greatly from it, but has remained largely unaware of the consequences, other than those which directly affect its economy. A workable and just U.S. immigration policy must take fully into account the consequences of emigration as well. Likewise, Mexico must no longer remain willfully ignorant of the consequences of unrestrained emigration and must negotiate agreements with the United States accordingly. Only if two countries work together, attentive to the indirect as well as the direct consequences of immigration, can the rancorous debate be transformed into a constructive discussion and an acceptable, lasting solution be found. Published in In Motion Magazine, February 7, 2007 Also see:

|

||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2021 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |