|

Interview with artist Jose Ramirez -- Contemporary Latino life in Los Angeles -- Los Angeles, California

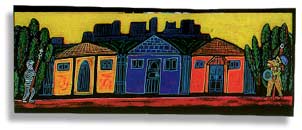

Abstract lines from pre-Columbian design Roberto Flores: In your early work, you used Aztec motifs as a background. How has your work evolved that you are not using those motifs as much? Jose Ramirez: My work has evolved in that it's branched out. Those motifs might be there in a not-in-your-face way. It's based in them. It's coming from them. And in some images, there's a lot of different directions that my work is taking. In some images it's more direct, and in others it's more subdued. The motifs might be on the walls of some of the images, if it's an interior image, or on the walls of the city -- stylized and abstracted. Originally, I was trying to do something that was more referential to a specific piece. Now, I've taken it in and it's coming out in a more stylized way. My work has evolved in that way. Roberto Flores: I see in your work different themes and takeoffs from those themes. For example, you might have the family theme, or the urban settings. The barrioscapes, I call them. In the barrioscapes themselves, what motivates you? Jose Ramirez: Different things. Sometimes it's a specific place that I go to a lot, or was part of me growing up. Other times, I want to show places that may be given a negative light by the media or people's impressions. I want to show the people in them, the colors in them, the connections with places. The colors, the images, the lines, the stylizations, the cars.

Roberto Flores: What you are saying, I get on a visceral level. I get a good feeling. A beautiful place to live. The love, the colorfulness, the relationships, the simplicity of the place, and how this is a working-class neighborhood. A caring place. The mother holding the child. There's family, there’s love in this community. The colors are very warm - hot sometimes.

Jose Ramirez: In a lot of them, I try to put the downtown skyline to reference that, to show the hierarchies. It’s far away. But real close to where I'm at, are the kids playing in the street, the adults walking or watching their kids. The colors. It’s all simplified. It’s been getting more and more simplified. Before, I would try to look at specific places and make them look, not photo realistic, but more realistic. Now It’s from here a lot of the times. Looking at a picture, but not continually looking at it to try and make it look the same. I feel more comfortable with my brush and what I'm trying to do, not creating just what the photograph looked like. I'm feeling more comfortable with being in the community where I work and where I live and grew up. Feeling more at ease. I was away for so long, studying. Now I have come back and I'm trying to find my place. I'm not necessarily saying that I have an idea of how It’s going to be done but I let it help mold me and then I offer it something. It’s a two-way play on that level. I try to reflect that in the paintings. We need to be here in our own places Roberto Flores: Obviously, Zapatismo has had a lot of influence in your work. Can you talk a little about where you think It’s taken you and how It’s impacted you?

Also I see that the Zapatistas are part of a continuum from the ’60s, the Chicano Movement, back through pre-Columbian art. I see that as something new for an artist. It is something that inspires. Educated on a lot of different levels Roberto Flores: A couple of your paintings that I've seen portray young Black women that I'm assuming were your students. Jose Ramirez: Yes, when I taught in South Central. Roberto Flores: This had an impact on me, coming from a situation where I've seen Chicanos just focus in on Chicanos, and not really expand out and look at the interaction with other people. It was really refreshing. Jose Ramirez: I've been very privileged in that I got to be educated on a lot of different levels. Not at just a university level and a graduate level, but also in Mexico with my family, and with my grandparents. I've traveled and seen a lot of places. This has opened up my mind to know that it's not just about painting an Aztec image. It’s not just about painting Chicano images. Taking it all in, we are part of this whole continuum of history and art history. You can try to use those images or reinterpret a lot of the images and not feel like it's only got to be a nationalistic kind of thing. This goes in with Zapatista ideology. I dealt with this at Berkeley too -- the nationalists, the hard-core Mechistas. I fit in more with people who are trying to work across cultures and build coalitions.

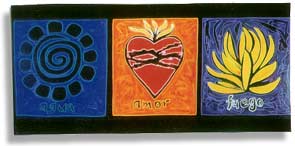

Roberto Flores: Yes, I thought it was really refreshing and beautiful to see a Chicano drawing on and about Blacks. Depicting them in such a dignified and beautiful way. I recently saw a video about Henry Sugimoto, the Japanese-American artist. He was interned during World War II. He was also influenced by Diego Rivera. He did some art relating to the campesino and that too was really refreshing. Jose Ramirez: It’s interesting because in the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s there was a whole generation of African American artists directly influenced by the muralists in Mexico. Some of them went down and lived in Mexico. You see it in some of the murals that were produced here by African American artists. There was an exhibit that went through the African American museum by USC that showed this history. It was about the Mexican muralists and African American artists. It showed both their works and their connections. Roberto Flores: It’s also very much in line with the spirit and thinking of Anthony Gleeton, the photographer who did a lot of work in Oaxaca, in Guerrero, where Blacks combined with the indigenous people. It’s very refreshing. I was going to ask you about La Loteria, your relatively recent use of La Loteria to put across different themes. I look at each one of those cards and I read a lot into them. Maybe I read too much into them, but the symbols you pick are not the regular Loteria symbols. They are very meaningful. Like the one “Ojo” which I think is a loteria symbol. Jose Ramirez: Yes, there have been a lot of different interpretations throughout history of la loteria. I think it's been around for 3 or 4 hundred years. I was given one of Jose Guadalupe Posada’s loteria images and was inspired, encouraged, by the art dealer who gave it to me, to do a series of loterias. I saw it and I saw that a hundred years ago this guy was doing these intense images for la loteria that could be put together in a political way. I thought, I've got to use these. When I started to do my own, I looked at my old paintings and I said I like a particular image, why don't I put it with this image, and this image, and I then picked an image from the old loteria and then they say something. I read into them a lot, as well. It’s been a lot of fun to put these paintings together with that in mind. Even three or five together in a certain way can say a lot about a specific incident or something in general. Reinventing my work every once and a while can lead to a new idea with something else. It grows that way in here - in my studio. Not trying to speak in an academic language all the time Roberto Flores: What you've been saying is that when you do art, you do it for everyone. Your audience is everyone. It’s not like when you are writing you have to think and delimit your audience and focus in on a sector of everyone. It seems to me when you do art you are trying to be broadly inclusive. You include children. The texture and the images and the strokes seem to me very much what children can do.

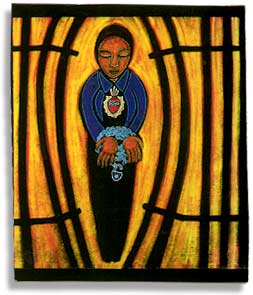

It’s frustrating when art only reflects something abstract or academic that people can't access. Roberto Flores: A very small portion of the population can relate to that. In terms of ancestors, the Ancestor series, the feel for me is that it's something deep inside us to respect the elders, and ancestors, those that came before us. It isn't something that the youth are that conscious of, or practicing that much. But it can be awakened. Is that part of your effort with the ancestor series? Jose Ramirez: Yes, and to acknowledge that we have ancestors on a lot of different levels, not just several thousand years ago, but our grandparents or our parents. Our elders in the community. These things are not just ideas that I'm visualizing but also other artists in the community are putting them to music, or to word, or to their actions. These are ideas that are out there and I hear people talk about. DJ Fidel Rodriguez of Seditious Beats was talking about ancestors. Quetzal's music is influenced and is reflecting on music that ancestors did. And so is my art. I hope that people can connect with it. We are not encouraged to a lot of times but it's something that could be very powerful. Roberto Flores: One of the other things I see is ancestors are not only people who ... the transition, the cutoff line of being dead and being an ancestor and being alive is not there. It’s like you can be living and be an ancestor. Jose Ramirez: Yes. Roberto Flores: The transition is blurry. What I see in what you are saying is the way to build barrios, the way to build community, the way to reach some of these Zapatista goals, respect, starts at the family. Jose Ramirez: I think that, yes, but unfortunately that is not the reality for a lot of the students that I work with. Sometimes being in a family can be very disastrous in some ways too. My experiences with my family and the family that I'm trying to build now with my kids leads me to be proactive. I'm actively trying to involve my work -- to be more pro-active, more positive. I'm not saying that I don't comment on negative issues or do painting that could be called political, but rather than being complaining and negative all the time, which is stuff that you go through, a phase of protest, I'm trying to evolve my work into something that is more positive, proactive. Roberto Flores: Your medium. You paint with oils on canvas but you also paint on plywood. Jose Ramirez: Acrylics on plywood. Sometimes paper. Before it was whatever I could find. Now It’s little bit more refined, or if I find wood then I'll do a lot of wood pieces. If I have canvas, then I'll make canvas paintings. But whatever I have around I work with. Roberto Flores: Is there a thing about making that accessible as well? Canvass you have to prepare, but a piece of plywood ...

Roberto Flores: Find in the street. Jose Ramirez: Yes. And a lot of times people who look at the work love that it's on plywood. They like that it has a big old gash going across it because they can see that it has its own history. And other times people are taken aback and they can't take it seriously. They are afraid to respect it as art because they think it's not taken seriously. Nic Paget-Clarke: I've seen a couple of your earlier works and they are black and white, grays, but the majority of your work is bursting with color. I'm wondering how that came about. Jose Ramirez: I think a big part of that is just getting better with paint, practicing. I try to paint a lot and to be conscious. As I said before, I would try to paint something that looked like something in a photograph. Now I have gotten away from that and I go straight into working with that flat piece and make that colorful. It’s more relaxing for me to focus on that. My work is more stylized. Roberto Flores: Do you think you'll ever do other earlier works, like the chalk Rodney King piece, in color? Jose Ramirez: I look back at my portfolio when I'm not sure what to do, what to work with next. And when I look back and I see something that I like I try to reinterpret it with color. This is what I did with the Notevejes piece. I had done that as a charcoal drawing five years ago then I did it in paint five years later with color. It evolved. I go back to some images and reinterpret them. So yes I would. I'm not closed to doing stuff like that, to having a wide range of things that I could do. For example, the show that I hung today in Long Beach has some pieces that could be considered angry or protest, but then there are others that are calm and serene and nice to look at. I think that that is OK to do. We are complex people. We are not just one-minded. We can think a lot of different thoughts. Just as musicians can do different things with music, artists can do different kinds of paintings. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Published in In Motion Magazine August 25, 2001. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World || OneWorld / US || NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2011 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||