|

Chapter 3: June 1994 - Tuskegee by Phyllis Alesia Perry Atlanta, Georgia |

||

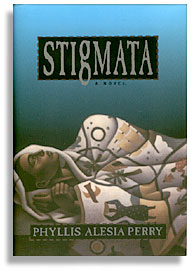

Her first novel, "Stigmata," was published in February 1998 by Ullstein in Germany and by Hyperion Books in August 1998. It was published in Great Britain in January 1999 and is scheduled for release in The Netherlands and Spain. "Stigmata" is a Book-of-the-Month Club/Quality Paperback Book Club Selection and has been nominated for the Quality Paperback Book Club New Voices Award. Perry received the 1999 Georgia Author of the Year Award for a first novel. Chapter 3 is reprinted from STIGMATA by Phyllis Alesia Perry. Copyright © 1999 by Phyllis Alesia Perry. Published by Hyperion. Available wherever books are sold or by calling 800-759-0190. Also available at cushcity.com, an online bookseller, and powells.com, an independent that sells both new and used copies of Stigmata. |

||

|

Stigmata

Chapter 3: June 1994 - Tuskegee

I go out and about in it my second day back -- slowly, I haven't driven a car in years; hell, I don't even have a driver's license anymore -- and everyone honks. I put the top down to invite the June sun in and let my sweat stain the seats. Necks flex as the occupants of passing vehicles realize it is not Dr. DuBose driving, but a stranger -- a woman with practically no hair who sings loudly through the town on her way to the grocery store. I suppose if I had kept the hair -- those shoulder-length ringlets that I used to toss as often as possible -- folks would have at least had a chance to recognize me. Tuskegee is the kind of town where people don't change much. Women walk into Lou's House of Beauty every other Saturday and put on the same heads of hair they've worn for decades. Or they sit at home in their kitchens where bootleg beauticians wield hot combs or plastic gloves and tubs of relaxer. Men sit in the sun outside of Mr. Clark's tiny barber shop, waiting their turn. They get their trims and shaves, and frown at the Tuskegee University students who roar through town with dreadlocks flying. Yeah, the hair might have been a giveaway, but the curls by Revlon are gone, as are the three-inch, petal-pink fingernails and tweezed brows. No teenager here, just a thirty-four-year- old woman who spent her first day back home yesterday staring at her blue-and-white bedroom, with the stuffed bears on the bed, the Prince poster on the wall, the teeny-bopper clothes in the closet. It was all the same, mostly, as the day I'd left fourteen years ago. That day they'd loaded me into an ambulance, bandaged about the wrists, for a ride to a hospital room with bars on the windows. Now, all these years later, I have the eerie feeling I'm living life in reverse. I guess I am just expected to pick up where I left off at age fourteen, from before that trunk came into our lives. But very old eyes had looked back at me from the mirror over the fake white French provincial dresser. The burnt-honey skin pulls so tight around my bones these days, making me look slightly surprised all the time, and my large eyes, like the hungry eyes of some animal, are all over my face. I'm all pared down, the surplus whittled away by bland hospital food and energy-sapping mental ramblings. It's not too bad of a look, though. My hands fit nicely around my head, now that the hair hugs the scalp. Moving one hand off the steering wheel, I run my palms over the crinkly springiness of born-again kinks. Mother had complained for years about that short, nappy hair. But, her hairdresser, Lou, doesn't make house calls at Bentwood Mental Health Center in Montgomery -- or Smith-Rainey Residential Treatment Center in Birmingham or Parkside Hospital in Atlanta. And after the first few weeks at Bentwood, in a room with little in it but sheets and a nightgown, those chemical curls on my head began to grow heavy. One day I got an attendant to cut them, and I slipped into my real hair, feeling clean. Now Mother perhaps will want to throw some lye on it right away, but I'll find some way to distract her. Hell, I think as I shift gears and pull into the grocery store parking lot, Prince doesn't even use his real name anymore. Things change. When I get back home with the cheese and eggs for the macaroni and cheese Mother plans to make that night, she is in my room, her head buried in my closet. We'd begun cleaning it out that morning, and Mother had dived in with a relish that was unabated, even after several hours of filling boxes and flinging dust. "No, no," I say, coming in as she is about to toss still another '70s relic into a cardboard box positioned near the doorway of my bedroom. "Don't put that in." Mother looks at the blue cotton shirt she holds in her hand and then back at me. "Why not?" she asks. "I need it for something." I take it from her limp fingers, fold it and add it to a stack on my bed. She shrugs and dives back into the closet. "What are you going to do with those old things? I said I'd buy you some new clothes, Lizzie." She pulls out a pair of black patent leather shoes and laughs before tossing them into the box. "A project," I answer. "Why didn't you and Daddy get rid of this stuff?" "Well . . . it's yours." She throws something else in; I peep into the box, but decide to leave it. "After that . . . time . . . " Her voice trails into a jerky sigh. "I didn't know what to do . . . I just knew you'd be back in a week or so." "Funny how time flies," I say, trying really hard to keep the sarcasm out of my voice but not hard enough because I see her wince. I guess I'm still a little mad. I'm not supposed to be mad. I'm supposed to be reclaiming my family. I glance at her profile, noting the pucker just above her eye brows. "Sorry," I say. "Well," she says briskly, closing the box lid and anchoring it with masking tape. "It's done with. Behind us. You got through it all and you're all right now, right?" My mouth opens, then closes. Am I all right, down inside this lie? I can't say, and she is gone anyway, looking for another box. And the third? Grace's trunk. I look for the trunk. When I ask Mother about it, she always finds a way to get busy. Really busy. "Now," she will say, as she rearranges the corner of a rug that keeps slipping underfoot in the foyer, "I'm trying to recall where -- I kept it in the attic . . . but no, I had to move it for that other box. You know, baby, I'm not sure where that trunk is right now. But it'll turn up." Now, Mother never misplaces anything. She knows when the centerpiece of papier-mâché fruit cradled in the crystal bowl on the dining room table is one centimeter off-kilter. There used to be a woman who came in once a week to "do" for Mother and she got her feelings hurt a lot until she understood her place and our place and the way things were supposed to be. Our house is a shrine to middle-class order. Not just neat, not just clean, but true to the standards demanded by our position in this little belch of a town. Mother has a place for everything, including herself, and I know the whereabouts of that trunk are a mystery only to me. I spend two whole days looking for it. The attic first, then all the closets and crannies about the house. I remember the attic being a sweatbox in summer, but now there is a big fan going on the roof, creating a slight breeze through the top of the house. When I can't find it, I ask her again, and Mrs. Dr. DuBose looks so scared that I shut up. I mean, she is a sixty-year-old woman completely unaware of her own immortality. She might have a heart attack if she thinks I'm losing it -- again. The logic is good. Out of sight, out of mind; or in my case, not out of my mind. Not that I ever was. But she doesn't know that. The only trouble with the Winn-Dixie is that you see everybody you ever knew in there if you go often enough. My second time in there I rounded a corner to find my old fifth-grade teacher staring, not at my face in recognition, but at my scarred wrists. She aims her buggy in my direction and I think, I'm just trying to buy some oranges. I'm just trying to buy some oranges and this woman is going to try me. Her name pops up from somewhere. Mrs. Penn. Why does everyone seem to shrink? I wonder, as she cautiously approaches. I know I've turned into an Amazon since grade school, but surely she is smaller. How does there get to be less of you? How does the body just fold up like that? I very quickly make a request to God. Being nearly six feet, I don't think my body would take very well to folding. Mrs. Penn is well turned out in a crisp white dress -- looks like linen -- and a small white hat firmly atop coal-black, shiny hair. I think it is the hair I recognize and not the face. Her buggy in front for protection, she slip-slides toward me in white terry bedroom mules -- totally out of place with the rest of her. "Well," murmurs Mrs. Penn, parking alongside me with painstaking care. A loaf of white bread and a tomato lie in the bottom of her buggy. "Well. Elizabeth DuBose. Uh-huh. I thought it was you. How are you, girl?" I try to recall something about her besides the name and the rather useless fact that I once sat in a wooden desk in her classroom -- middle aisle, three rows back -- at Our Lady of Mercy. I remember being disappointed that she wasn't a nun. I'd always been taught by nuns until then, and they fascinated me with their pink faces and their pink hands that disappeared beneath their voluminous clothes, only reappearing to point or hit. Our Lady -- the church and the parish schools -- is an island of lukewarm Catholicism in a town that teems with black Baptists and Methodists. Mrs. Penn was the first black teacher I had, and I guess that is how I placed her at all; a miracle, really, considering all the many years of mental disorder between us -- and I'm not just thinking of my vacation from accepted society. Looking at her softly triumphant expression, I know she considers herself quite brave today, seeing as how she is looking straight into the eyes of a pure-tee, board-certified crazy person. "Mrs. Penn," I say, leaning a little closer, hoping to scare her. "You're looking well." She stands her ground, even inching closer. I'm mildly surprised, even a little proud of her. "I try, baby. I see you're back." Her lips stretch into a smile I recognize from a couple of decades ago. "They treat you all right in there?" She whispers now, then releases her death grip on the buggy and pats my hand. "I don't know yet, Mrs. Penn, whether they treated me all right or not. When I find out I'll let you know." I really don't know. I'm alive. My thoughts now march to the right rhythm. So maybe they did treat me all right. "A11 right, then, baby." She withdraws her hand. "So, what are you up to now?" "Um." Can't answer that one. "I . . . I really just got here. Helping Mother around the house and stuff . . . you know." "Well." She laughs, and I hear sarcasm. Or am I too sensitive? "It's not like you have to work, right? Your daddy . . . well, you can take your time. Did you ever finish at Tuskegee University? You were such a good student. High school val, weren't you?" "Yes, ma'am. And no, I didn't finish college." "Um-hum. I thought so. I remember you being real good in school, though." Escape. Just around the corner of that aisle. I just begin to consider sliding the buggy that way when Mrs. Penn says, "Well, I've got to finish here. You tell your daddy I asked about him, hmmm?" She takes the helm of her buggy once more and moves off.

Frank got Mama garden turned over. She say she gon wait another week though cause she say more frost comin. Meantime she makin a little dress. Feed sack dress embroidered with flowers for the girl baby she say is comin. Aint no baby comin Mama I say. I been married a long time now and aint no baby come. You know how me and Frank pray for one. But she act like she dont hear. She cant get here cause Im in the way she say. But when Im gone she come to take my place. She gon know thangs the one thats comin. She'll know things and that knowin be a gift from me her family thats lost. And I say Mama I get tired of you talkin all bout stuff that aint real. And she say you can get tired all you want Joy Im gonna tell it till I die. |

||

| Published in In Motion Magazine October 26, 1999 |

||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2020 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

My father gives me his 1965 red Mustang convertible. Surprises me, but I take it. I might be two steps from crazy, but I'm no dummy. I understand that he has rewarded me for being on the right side of normal. More where that came from, his weary eyes promise as he hands me the keys. If I stay right. Everybody in Tuskegee knows that car. Cherry red, white leather interior, original chrome hubcaps. No one drives it except my father; he won't let Mother near it. It is the only object in his life that is the least bit -- uninhibited.

My father gives me his 1965 red Mustang convertible. Surprises me, but I take it. I might be two steps from crazy, but I'm no dummy. I understand that he has rewarded me for being on the right side of normal. More where that came from, his weary eyes promise as he hands me the keys. If I stay right. Everybody in Tuskegee knows that car. Cherry red, white leather interior, original chrome hubcaps. No one drives it except my father; he won't let Mother near it. It is the only object in his life that is the least bit -- uninhibited.