|

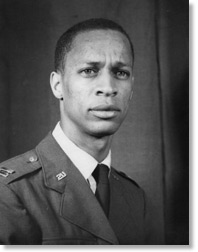

Afghanistan and Pakistan – Another View by Ja A. Jahannes Savannah, Georgia 1966-68.

I had accomplished my mission. I got a commitment for hundreds of reams of toilet paper in case the C-130 airplane that brought in our supplies was delayed another week. This was a catastrophe worth avoiding as the commissary was just about out of tissue and nearly 2,500 people depended on it. But I was more intrigued by what the elder had put in my hand, which I did not open until my driver was gone and I was in my second floor apartment at the huge off-base bachelor officers’ quarters called the Shaheen Jala (the "Eagles Nest"). All of the other officers and civilians living at the Shaheen Jala had gone to a party on base, about 4 miles away. I opened the paper covered object in my hand and it was a nugget of hashish. My nose had been rightfully suspicious as we drove down through the Hindu Kush of the Khyber Pass. The Pathan elder had put the first difficult lesson of living in this region of the world in my hand and I have pondered it ever since. What are the surprises, challenges and dangers of intercultural involvement with peoples whose history and evolution of traditions are far different from my own? Needless to say, I did not report all aspects of my previous day’s adventure to Colonel Graydon K. Eubanks, the base commanding officer, and my boss. After all, I was the Executive Officer and second in administrative command of the base, though there were colonels here and there who had very specialized jobs, they never interfered with the day to day operations of the base. Instead, those mundane matters fell on me, a 26 year old U. S. Air Force captain who was not only serving as Executive Officer but as Chief of Protocol as well. In truth I was only a boy. Still, an assignment to this airbase was noteworthy since Gary Powers and other U2 spyplane pilots had supposedly flown their top-secret reconnaissance missions over the Soviet Union from this classified secret location; secret that is until the a crass though wily Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev put Powers on public display after he was shot down over Soviet airspace. As illustrated by the story of the old Pathan and his gift of Hashish, I learned early and well during my assignment in Peshawar that the obligation to extend hospitality is fiercely held among the Pathan; as is the obligation to protect guests at all costs; those traditions are thousands of years old. That lesson was drilled home to me over and over again. Despite what has been written, this region has never been conquered by any army. At around the age of 8 or 9 each young boy is given a rifle and told he is a man; he must defend his honor, his family, his tribe, and any who are offered refuge in his home. It is unthinkable that anyone would break these traditions. And the land that the Pathans occupy covered parts of Afghanistan and Pakistan. It is called the Northwest Frontier; neither the Afghanistan nor the Pakistan governments have ever been recognized as having sovereignty over these people. We were also warned when traveling through the Khyber Pass not to stray 10 feet from the road. As long as we are on the road we are protected by local custom but once we leave the road we have strayed into tribal territory and may be shot on sight. These are not lessons I learned in history books or tourist guides, I learned them firsthand. A week later, I confessed to receiving the hashish gift to my next door neighbor, a civilian contractor who loved being called a Georgia redneck because he was smarter than the people who thought the term a put down. Fred laughed and asked "What did you do with it?" "I flushed it," I said. "Sure. Good man," he said. The men in Thieves City were masters at duplicating items. They could make anything and guns and rifles were specialties. However, sometimes they would spell a common word wrong; like "Made in Franc" and leave off the "e." There was also "honor" among the men in Thieves City. I would cut out a picture of suit or shirt from GQ, write out my measurements and send it by a perfect stranger going that way with a deposit and the next week the items would arrive in a package at my door, in perfect condition and at 5% of the cost. So efficient were the Pakistanis at duplication, the M. Havat Brothers in Peshawar made a replica of Kennedy's famous favorite rocking chair. Later, I had four intricately carved, exquisite Chinar screens, no two of which are alike, made of rosewood from the Havat Brothers and shipped them back to the U. S. at my own expense with a prayer that they arrive. They did. On yet another day, I decided to take off and go up to Thieves City to buy some replicas of vintage guns and rifles to hang on my walls when I returned to the states. I hired a driver and a van early in the morning. I watched the glistening white snow on the top of the mountains of the Hindu Kush as I did every morning from my apartment. It was 108 degrees that morning and I knew it would get a lot hotter before we returned with the guns. Near 10 a.m. the driver asked if we could stop for tea. It is a local custom to have tea quite regularly so I accommodated him. We stopped at a little hut along the road. He asked if I would like tea too. Still being culturally accommodating, I said "yes." At about 5 pm I was super relaxed and no longer so keen on the guns and rifles, so I told my driver let’s go back. He said "okay." I slept all the way down the Khyber Pass. The next day Colonel Eubank asked me when I was going to show him the guns and rifles. I told him the story. He said you were drinking "green tea." He explained that here this is opium tea and I wasn’t the only one who had fallen for it. He also explained that this same tea was what they served in the merchant shops in the Peshawar. That explained why I often came back to the base with items I couldn't imagine I wanted. That, coupled with the narrow streets and the smell of hashish everywhere, is enough to make a nation nod through history. I often went by plane to Kabul in Afghanistan. It was a beautiful exotic city where all the bazaar doors were painted green. It was a photographic delight to take long shots of the city streets green door bazaars before they opened in the mornings, which meant getting up very early. The bazaars were fun, lots of haggling and if you weren't wise you never knew what you were getting. I bought a well made sitar because Indian musician Ravi Shankar had made the sitar famous worldwide. I bought a rubab; another exotic string instrument because it looked like Noah’s ark and I was assured it was centuries old. I later learned from a reputable antique dealer that it was rubbish, not an antique and poorly made. I had been hustled. But at least, I had one. On a captain’s salary I could not afford to buy the one thing that would have been a lifetime treasure, a richly woven carpet whose colors would not fade for hundreds of years. Had my wife and family been with me, I’m sure she would have insisted we sacrifice to buy one of those carpets. But I was assigned to the base as a bachelor, to bring your family increased your commitment to serve an additional two years from the point of the family's arrival and it was never certain when travel for a spouse or family would be approved. I also went to Kandahar, Afghanistan for relaxation with military and civilian friends, and we enjoyed the picturesque tranquility and greenery of that special place. My next big lesson was crushing to my ego. One night I boldly decided to walk down the road from the Shaheen Jala towards the University of Peshawar. It was a large university only blocks away but I had only seen its entrances by day. I wandered onto the campus and slowly got lost in darkness. Then this quiet voice spoke out of the darkness "Are you lost? Do you need some help?" I said "Yes. I’m trying to find my way back to the entrance." "There are many entrances," he said. 'I will take you back but would you like to have tea with me first?" His name was Waris Ali Khan, a young engineering instructor at the university. We went to his faculty quarters and he had his servant make us tea. I was getting use to this tea business and this tea was not the opium tea of my previous encounter. Waris was the same age as I was. He was a soft spoken, humble man but it annoyed me that this young Pakistani knew more about almost everything we talked about than I did, including American history. I could not believe how well read he was and how patient he was at my being wrong on so many things. When I got over that we became fast friends, like brothers. At least twice a week we met for tea and to discuss the world, though my colleagues at the Shaheen Jala could not believe I invited a Pak (that's what they called them) to dinner and went God knows where with him. Fortunately this light brown skin color that I was born with was a ticket to many places others could not go. In everyday clothes -- a shirt and slacks and the traditional sandals of Pakistani men, I could get lost in the crowd. But in the Shalwar Qameez and a Pukul Hat -- traditional Pakistan clothing -- I completely disappeared among my Pakistani friends. That color, over the years became a blessing in Ethiopia, Egypt, Brazil, the coast of Colombia, etc. One weekend Waris took me to visit his older brother at a distance Pakistani army base. All was going well until I ordered breakfast. The place became quiet. A superior officer spoke to Waris' brother and we were driven into town to one of the fine restaurants with breakfast paid for by the Pakistani air base. When I spoke at breakfast, they discovered I was an American and in a classified area of the base. Waris' brother came to breakfast with us so they had that time together. I remember that breakfast well; Waris coaxed me into to eating goat's brains scrambled in eggs. Wasn't bad but I've never tried it since. When I returned to my base that Monday, my commanding officer said it was unlikely that anything would ever happen to me in Pakistan since he had learned that now the Pakistani security was keeping a constant eye on me and so was American intelligence. It seemed thereafter that everywhere I went somebody knew. Waris and I were friends for a year and a half until the inevitable happened. He was in love with this Pakistani girl in Rawalpindi who also loved him; he had saved all his money from his job at the university to convince her father he would have a proper dowry to pay the bride price for her. Her father did not wait and married her off to the young man he had in mind. Despondent, Waris took the first offer of a job to teach engineering in Frankfort, Germany. We only corresponded once after that and I no longer had his address after I came back to the states. I have tried many ways to reach him through the University of Peshawar, through the embassy and the press. Waris Ali Khan is a very common name in Pakistan. I doubt I shall ever see my friend again, but he will always be my friend. My other Pakistani friend was Moin Malik. He was two years younger than I am, rambunctious, liked to hang out late at night and told the funniest jokes. His father was a general and I was treated to all the trappings of upper class Pakistani life, invited to all the festivals and treated like family. I observe customs very well and did not mind asking a simple question to keep from making a fool of myself. We never discussed religion or politics in front of General Malik. With Moin, it was altogether different than with Waris; he preferred pretty girls, fast horses and hanging out in the night clubs better than religion or politics. From Moin I learned to take it easy. We hung out a lot in the city and many times the Americans I saw everyday did not see me because I was where they had not expected me to be. I loved the religious festivals at General Malik's compound. He never tried to proselytize me but he wanted me to have a clear understanding of the ceremonies and what each ritual meant. Once when the Shah in Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, came to Pakistan, and there were very few tickets for the ceremony and fly over in honor of him, I was without a ticket. Moin was not interested in such things but told his father that I was disappointed that I could not go. The general got me a ticket just outside the VIP box, sitting at the feet of Iranian queen, Queen Farah who was considered one of the most beautiful women in the world. Several times she smiled at me; I looked down on my commanding officer and his entourage as though I belonged up where I was. I wore a suit known until that time to be owned only by the Wali (King) of Swat. It was a flame resistant unusual silver material with a Nehru collar -- courtesy of my copy from an American men's fashion magazine. In the two years I lived at the foot of the snow capped Himalayas, I learned of the fierce pride of the people, that government is by tribal leaders not people put in office, that people take their traditions of thousands of years serious and reverently, that no man is ever turned out once he is accepted as a guest, and there are always other lessons to be learned. © 2010 by Ja A. Jahannes Dr. Ja A. Jahannes is a writer, psychologist, educator, and social critic. He is a frequent columnist for numerous publications. His work has appeared in a wide-ranging spectrum of publications. Dr. Jahannes has lectured throughout the U. S., in Africa, Asia, South America and the Middle East. Also see:

|

||||||||||

|

Published in In Motion Magazine October 4, 2010 |

||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World || OneWorld / US || NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2014 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |