|

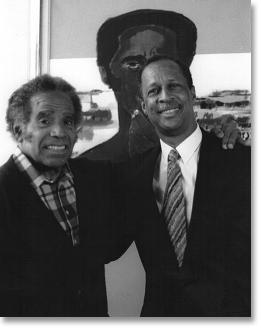

Manuel Zapata Olivella – South America's Voice of African Consciousness Interview by Ja A. Jahannes Photo by Magdalena Agüero Bogotá, Colombia

Jahannes: W. E. B. DuBois said "The problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line." Was DuBois correct and what are the prospects for race in the 21st century? Zapata: I believe that DuBois was correct when he said that the 20th Century would be the century for "colorization." Maybe this will continue into the next century. In the 21 century, people may begin to have a conscience about the past century and begin to fight strongly against the consequence of that colorization in the past. I suppose that in the 21st century the problem of "discolorization" will be the stronger because it will be not a question of black as it happens in America or Africa but the people of the Third World will suffer the same, people in Asia, people in the middle Orient people. These people will be fighting "decolorization" in the 21st century. Jahannes: Fifty-two percent of Colombians are Black. How do Colombians of African blood fare in Colombia? Zapata: In Colombia, because we have had a continued integration there exists many mulattos and mestizos. Most of the descendants of people of African blood live in the countryside. In the cities, in the urban area, and so forth, most of them are mestizos. In Colombia, most of the black people live in the Pacific Coast. They have little social implement. They have no education or schooling. They have no way of communication. They do not have very good health aides, but what characterizes this region is that blacks have developed their own culture. That does not mean that this culture is African culture, but they have changed their way of life and they have developed a new culture in modern times but in that imagined situation of which they have been told of before. Jahannes: Who are the leaders of the African world in Latin America today? Could you name some of the principal people besides yourself? Zapata: That it is not a very easy question to answer because there are many of them. In Brazil, there is Abdias do Nascimento, Joel Rufino Do Santos, and Gorge Amado. In Peru Licenciado José Campos Da'nla. In Venezuela, Frederico Buto Figueroa and José Marcial Ramos Guedez. Over in Panama, Gerado Maloney and in Costa Rica there is Quince Duncan. Nancy Morejon and Rogelio Martinez Furé in Cuba and in Ecuador, Nelson Estupiña Bass and Adalberto Ortiz. Rex Nettleford is a principal leader in Jamaica. Jahannes: Your own contributions to African consciousness in Colombia and Latin America are enormous. What inspires your work and what do you consider some of your most significant accomplishments view? Zapata: I have, with another fellow, organized the Congress of Black Culture in America. The first one was here in Colombia in Cali in 1976. The second Congress was in Panama in 1981 and the third one was in Sao Paulo, Brazil in 1984. For that Congress, we tried to invite all those persons who were interested in black culture in the Americas. Most of the delegates were black people who came from different places; from United States, from Brazil and from Central America, and so forth. After this first step to try to develop Black consciousness in this continent, we have been working through literary expression, through meetings of anthropologists who are working in this area. I believe that in this moment, after 20 years, we have had developed a consciousness about blacks in American culture. Jahannes: Why is it difficult to get Latin Americans of African descent to own their African heritage? Zapata: This is different in the different countries of this continent. For example, in Brazil there exists a very strong consciousness about their African ascendants because in Brazil they have had the facility to reconstruct their culture. In Brazil, most of the blacks come from the same place in Africa. That does not happen in any other country in South America. In Hispanic South America, there is no place to trace black people from Africa because they were bought as prisoners in Africa from the different traders and from those traders from. Blacks who arrived in the Hispanic colonies did not come from the same place and therefore they did not have a singular culture as happens in Brazil. Jahannes: In Colombia? Zapata: The port of Cartagena De Indias in Colombia was the most important port where the ships of African prisoners arrived in the Hispanic colony in the continent. For that reason, we have had African prisoners from different countries of Africa. Most of them were not able speak between themselves because they spoke different languages. Consequently, we do not have a very strong African culture. Our ancestors were not able to preserve their roots. Most of the black who have arrived in Colombia were carried to the Pacific coast. On the Pacific coast of Colombia, they were not able to preserve their African culture but after the abolition of slavery here in 1862, they were free and they began to develop their own culture. That meant preserving a small part of their African culture and modifying their ancestral memory, trying to construct a new culture with those elements that they have received here from the Spanish, from the Indians. Most of the people of the Pacific coast of Colombia are Black. Ninety-five percent of the population is black. Yet, as I said, they were not able to preserve their African culture. In this new situation that they have preserved only some Africans instruments, like the marimbas and colloolas, and some African dances. Still, most of these dances have Spanish influences. The names of these dances are shada, cotradanca, and hota. In the Pacific Coast they preserved very good song traditions that have been taken from the Catholic missionaries, but they have adopted this influence and have developed what we can call a kind of spirituals, a new conception of the chants that they have received from the missionaries. Jahannes: What about other African retentions in the Pacific coast of Colombia. Are there African retentions in food, behavior, mannerisms or spirituality? Zapata: We have very important African influences in our culture in general. Not only between the black people but with all people. For example, all of the population of this country knows what we call myoma. This is a plant from Africa. It is very cold in the Atlantic coast and Pacific coast of Colombia. The banana, as you know, we have received from Africa. Mealo, this is another food plant that we received from Africa. In dress, we have not a particular kind of dress from Africa, but we use some piece of African dress; that is what happened with the handkerchief that we use on the head or on the neck. We use in the Atlantic Coast what we call arbacas, a class of shoes that was used very much in Africa for those people who tried to carry cows. Where we have a very strong influence is in behavior. Most of the people in the Pacific coast, and even the Atlantic Coast, have very strong African influence. For example, we are polygamist. We know that polygamists is not only from Africa because the Spanish were polygamists and the Indian culture was polygamous too. There is another important influence that we have received from Africa. I am very much convinced that the more important contribution of blacks to the American culture, from the North to the South, is the fight for liberty. Because here in the Americas, the only people enslaved were blacks so they began to fight against slavery in the United States and in South America. So the spirit of liberty that we have in all continents comes from the attitude toward liberty from the Africans. Another very strong contribution of blacks has been religiosity. People from Africa, as everybody knows, are religious. This religiosity does not mean a cultural practice of a specific cult as it happened in Cuba, Haiti or in Brazil but the attitude to believe that everybody must be obliged to preserve the conscience of a god or many gods. Another contribution of blacks to the attitude of people in this continent is to fight for land. The Africans, when they arrived here, were very conscious that they would not return to Africa and for that reason they were trying to fight for land in this continent. Jahannes: I understand that intellectuals in Colombia acknowledge your contributions to social thought but claim that you divide the society along racial lines. Are they afraid of you and why? Zapata: In reality, here in Colombia, we have had only a few black intellectuals in the past or in the present that have been fighting for the dignity for black people. In the past century, we had Candalabrio Wyes, a poet who wrote a book of poems in which he expressed the feeling for liberty of the blacks in the past century. Also in the last century, we had another good speaker whose name was Luis Ab Lodela. He was a very important black man in the past century. He was a speaker, and a member of the Congress. In the middle of this century, we had Luis Galgoa, he was a political leader and he was a member of Congress for more than 25 years. In literature, my mentor, Gorge Ata, my teacher; he is a very important poet in Latin American. He wrote a book entitled Dark Is the Night. Another leader, who died ten years ago, was N. Dias. Dias came from the Pacific Coast and was a member of Congress and Parliament. From 1914 onward, Dias began to develop black consciousness in this country. My sister, Delia, who is an internationally known dancer, my brother, Juan, who is a physician and writer, and I have continued this tradition. Promoting black consciousness is not something that we have developed at this time; we received from the past these various examples for the fight for our rights here in Colombia. When people say we are trying to divide society, they have forgotten or they do not want to remember that for more than three and one half centuries, our society was divide along racial lines by the colonizer; they put on one side the black, the other the side the Indian, the other side the white people. What we try to show is why now in Colombia, in our society, there exists very strong prejudice, a very strong heritage of that colonialism that divided our races, our people. I do not believe they are afraid of what we are doing, but try to maintain the idea that in the country of Colombia we do not have racial discrimination because that way they have power over the different races. Zapata: What do you see as the future of Colombia in culture, in civilization, broadly? Jahannes: The problem for the development of our country is the problem of development of those races that have been oppressed in the past. More than 75% of the population of Colombia are illiterate. Illiterate people in Colombia belong to the descendants of black people or are the descendants of Indian people. So, when I speak of the development of this country, and generally throughout South America, I say that for the people who have been discriminateded against in the past century, in Colombia and throughout the world, is the challenge of the technical development. We know that we must have a large scale evolution of our universities for our culture in general. And, if this is not the way for our oppressed people, the future of our country as a whole will not be very good for us. Most of our people, the blacks and the Indians, do not have to go the university, and, therefore, they do not the opportunity for a high level of life. Jahannes: As a writer and intellectual your contributions have been enormous. Can you describe for us the essential themes of your works? Zapata: This is not necessarily difficult and can be summed up quite briefly. All my work tries to show the situation in which the poor people of my country live. Since the first of my work to the last work I have only said the same thing: liberty, culture and dignity for the poor in our country. Jahannes: You have been friends with some of the most outstanding contributors to culture in the Americas. You were friends with writer and poet Langston Hughes. Zapata: Langston Hughes was a very strong influence. Hughes was a fighter for human dignity; he was not only a poet but a leader of black people in the United States. I knew Hughes since 1946. Since that time until his death, we exchanged our opinion through our books. He faithfully sent me copies of his books and I have sent him mine. Jahannes: How did you come to be a friend of the painter Charles White? Zapata: I met Charles White one night in the home of Langston Hughes. Hughes had invited different artists, singers, musicians to meet me. I remember two persons in particular. One of them was the legendary actor and singer, Paul Robeson and the other Charles White. As I lived for four months in New York, I had the opportunity to know through Langston Hughes, Cab Callaway, Duke Ellington and Richard Wright, the distinguished American writer. That is what I remember now. Zapata: I first met Senghor in 1974. We had organized a conference on Negritude. It took place in Dakar, Senegal. After this first meeting with Leopold Senghor, I had two more opportunities to be with him; one in Paris and another in Miami. The University of Miami organized a homage to Senghor and Aime Cesar. There I had the opportunity to see him for a second time. In Miami for the first time, I had the opportunity to know, Aimé Cesar. Cesar is for me and those African writers, a writer of the most important, necessary work. Cesar showed us how to use our language, to be proud to use our traditional language, not to repeat the language that had been introduced by the colonizer, with the spirit of that colonizer. The language is the same but the spirit is different. Aimé Cesar contributed very much in this attitude in literature in Latin America. I knew Leon Damas, too, in the United States at Howard University. We were together for one semester. He was the director of the Anthropology Department at Howard University. I wrote a chapter about Leon Damas that was printed in the portrait of the book written on those who assisted with establishing the first Congress of black culture in the Americas. Jahannes: You also know Margaret Walker. Quite recently I participated in the congress of black women writers to honor Margaret Walker. The theme of that Congress was "magic realism." I understand that in your novel, Hemingway - the Hunter of Death, you use magic realism. What is magic realism and how is it useful as a literary tool. Zapata: Magic realism is not easy to explain but I will try. For me magic realism is more than a form to express the soul of the artist. It is a way to interpret the African and Indian tradition in literature and theater. That does not mean that all we have to do is to think of something in the imagination. Undoubtedly, magic realism today is a characteristic of the new Latin American literature as a function of expressions of marvelous situations that correspond to the world of magic. Magic realism in Latin America is influenced by African and indigenous Indian culture. It gives the possibility to conceive the world from a new viewpoint, different from the limited, pragmatic view of the European philosophy. In this sense, I used magic realism in my last novel, Hemingway The Hunter of Death. In that novel, I confront the thought of North American Hemingway with the thought of the small villages of Kenya's Kikuyu, throughout one of Kenya’s most important intellectuals, Jomo Kenyatta. I confront the thought of Jomo Kenyatta defending the traditional philosophy of his town with the thought of Hemingway trying to understand a village in Kenya. Magic realism is used by the new writers of the Americas, particularly those of African descent. Magic realism for these writers has a different meaning than the one that is recognized by mainstream Latin American literature. Jahannes: What are some of the profound influences on contemporary black intellectual thought in Latin America? Zapata: We have three important influences from black intellectuals by way of the United States. One is from W. E. B. DuBois, another from Marcus Garvey and another from Frantz Fanon. Each has influenced my evolution. After those writers, we have the influence of Malcolm X another America freedom fighter, not American black writer. Marcus Garvey gave us the consciousness to fight for organization. Dubois gave us the consciousness of Pan Africanism. And Fanon gave us the idea to fight against cultural alienation. Jahannes: You have studied early Latin American anthropology and history. How do you describe early African intervention in the Americas such as the Olmecs? Zapata: One theme has been not very clear in our history in America in the origin of our man. The traditional conception says that the first male who arrived in this country came through the Strait of Bering. They say that those people belong to the Mongolian race but the important anthropologist, forgot the name, disagreed. The more important contribution that we have received more recently about the origin of the man in this continent belongs to Paul Veian. Paul Veian is the painter of the Musée de l'Homme (Museum of Man) in Paris. He lived for 20 years here in Colombia. He has a theory that the first man who arrived in this country had come from Melanesia and Polynesia thirteen thousand years ago not as it is known for more general information that the first man who arrived here arrived through the Strait of Bering from the Mongolian race. But, the thesis of Paul Veian has not been accepted by the American anthropologists because they do not want to admit that the first man may have come from Melanesia and Polynesia. The Olmec culture in Mexico is one of those people who have arrived from the Pacific coast from New Guinea and they developed in Mexico their own cultured called Olmec; you can find in Colombia, Panama, Peru, and Bolivia many sculptures that show black people in their culture because Melanesian people who have arrived here came to different part of the continent, not only Mexico. Jahannes: What is the name of those people who arrived here thirteen thousand years ago? Zapata: This is the Moha. They have stone sculpture in ice land of Pascua, Chile, more than 100 statues from the Moha, very high. All the anthropologists accepted that these are from the Melanesia culture. Jahannes: Tell me about yourself, your family. Zapata: I was born in a little village near the Caribbean coast where there is a melting of race between Indian, black and Hispanic. I studied medicine here in Bogotá. After practicing medicine, I became interested in anthropology and cultural linguistics because I needed that for my writing. My great passion has been to be a vagabond. I began to travel through the world in 1946 through central Mexico and the United States. That's when I met Langston Hughes. After I finished that travel to Central America, Mexico and the United States -- it took more than four years -- I came back to Bogotá and finish my study of medicine. I then became interested in anthropology because I saw the ballet of Katherine Dunham in Cartagena. My sister, Delia, finished in that year, 1946, her study of sculpture at the National University in Bogotá in the Academy of Arts. She and I were very strongly influenced by Katherine Dunham. Delia forgot her artistic work and I forgot my medicine, we tried to organize another dance group which happened in 1954. After two years organizing different folkloric dance groups here in Colombia, one of them a black troupe of dance from Chocó, we began a tour through Europe, and Asia for two years. We were in Russia in the Bolshoi Theater, we were in the Playee Theater in Paris. We were in the Theater of the People in Peking. We obtained the first prize of dance that took place in competition 1958 in Spain. After this we come back to Colombia. My sister continued directing her dance group and I became interested in the linguistic culture and I began to pay more attention to my literary creativity. After that, for more than twenty years, I have studied black culture in the Americas - in Brazil, Mexico, and the United States in order to write my book, Chanco The Grand Putas. And now, I have published my last novel, Hemingway-The Hunter Of Death. The important thing about Hemingway The Hunter of Death is its treatment of the Kikuyu one of Kenya. Maybe that is all that I can tell you. My book, Chanco The Grand Putas, I dedicated to my wife Rosa with this dedicatory "To Rosa, the companion of my birth." Jahannes: And you have two daughters? Zapata: Yes, I have two daughters. My eldest daughter is named Harlem, because I wanted always to remember my time in Harlem with Langston Hughes. And the other is named after my mother. Zapata: Well, I have another dedicatory in my book to my grandson and it says "To my grandsons, future fighting." That is my legacy, to be in the future fighting for liberty, fighting for dignity and the equality of the races. © 1993 by Ja A. Jahannes Dr. Ja A. Jahannes, writer and psychologist, is a frequent writer and lecturer on the African experience in the Americas, African American culture and esthetics. Magdalena Agüero is one of Latin America’s foremost documentary photographers and arts activists. Also see:

|

||||||

|

Published in In Motion Magazine October 10, 2010 |

||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World || OneWorld / US || NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2014 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |