|

Interview with Ela Bhatt

Founder of the Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) A good combination of struggle and constructive work Create, as a strategy, alternative economic organizations Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India

Ela Bhatt: I’m a product of the later years of the freedom movement, the independence movement of my country. As we were studying in school and then in college our teachers and everybody around was talking about independence. In the family, also, there was the atmosphere of the independence struggle. My own grandfather, my mother’s father, was in the Salt March. He was in jail. My mother’s two brothers were in jail. (Editor: begun March 12, 1930, the Salt March led by Mohandas (Mahatma) K. Gandhi was a 24-day march from his ashram in Ahmedabad to the Arabian Sea to make salt and protest the British ban of an Indian’s right to make salt.). When I was studying in college, our teachers asked us to go the villages and live with the villagers. Mainly against injustice, against poverty. We never had to question how to do it because Gandhiji had shown the way -- how to go about it and what kind of discipline you have to follow. There I met my husband (Ramesh Bhat) who was a student leader. I got married and I came to the same kind of family.That is what raised the consciousness for me. I am a product of those days. Next, as soon as I finished my law (studies) I joined the Textile Laborers Association, which was started by Gandhiji in 1917. I was working for textile workers. It was a union of the textile workers -- that is formal-sector labor. But, slowly, very gradually, there was a consciousness growing within me that there are so many other kinds of economic activities being done outside the formal sector, where there is no specific employer/employee relationship. What about them? I became more and more confirmed that if we talk of a labor movement worth its name in my country then it should include these workers who are outside the formal sector. I started calling them self-employed but economists and others call them the informal sector. Most of the production of goods and services is done by the self-employed. In 1972, they were 89% of the workforce, the active working population in the country. Today that percentage has grown to 96%. Their contribution to the national income is very significant but they are outside the purview of the labor legislation. They are outside the purview of rightful access to social security, access to financial services, welfare programs.Of course, after three decades, times have changed and slowly they have become more and more visible, but their political visibility is still not that powerful. A leading role in the women’s movement

These two things were getting more and more clear and confirmed in my mind. It is still the same. It has stayed with me to show me the direction. In ’72, we started organizing, unionizing the self-employed workers – women. And it took so many years to get ready for that stage. It was not so easy because the registrar of trade unions said, “How can you call it a trade union? Who is the employer? Against whom are you going to fight?” I argued that the purpose of a union is not only to fight, or to be against somebody, you also have to be for something. And that was for changing so many laws and policies. Women may not be able to pinpoint an employer but we have to fight against certain systems. Like the contract system. Like that whole range of middlemen, of contractors, and subcontractors, and sub-sub-contractors. That is something that is an exploitative system. Or with the public distribution system. Or with the marketplace. Or with the police – the police and the urban development policies who see street vendors as illegal. What we were questioning was, “What is illegal about street vending?” and therefore treating vendors like criminals, or like dirt. We have to fight on so many levels. Contractors, police -- one can see them directly. The workers can see them directly, those who are harassing them or exploiting them. But also there is the system which supports them -- government agencies, government laws and regulations, courts. You also have to fight at that level. And then there is still another level. At the national level and international level, there are certain perceptions about certain allocations of resources that you have to fight. From the beginning, I had realized that when you organize at the grassroots you have to have two-way communication. Whatever is happening at the macro level has to percolate down. Whatever is happening at the grassroots has to be conveyed to the concerned agencies at the national level and the international level. In Gandhi’s thinking

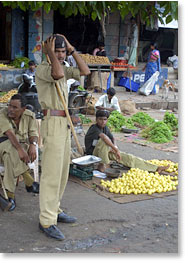

Ela Bhatt: In Gandhi’s thinking, in his design of development, the human being is in the center. He talks about human values. It may be your personal life or public life, political life, economical, the life of the nation, of the society, or at a global level – but for him certain values, human values, were central. And they were non-negotiable. His values are truth, peace, nonviolence. Also, in this change he put women as the leaders. He said that women are natural leaders in our fight for social justice where love and peace, nonviolence, are the chief weapons of the fight. In my experience, I have seen that it is the women who have brought the change. For example, we have been working in the desert area for the last few years, and it is the women who have been able to change the local ecology, regenerate the local ecology. It is the local women who have stopped up to 80% of the forced migration. Women have that capacity for social change by coming together and working on a peaceful basis. I have a great faith in that and I have seen in practice that it is possible. Civil disobedience and sit-in strikes In Motion Magazine: Did you ever use civil disobedience tactics in your struggles? Ela Bhatt: Yes, often we have to resort to that. Also, we have gone on strike as the last weapon, the last tool. We have sit-in strikes. We have satyagraha (editor: insistence on truth – nonviolent resistance). In Motion Magazine: Could you give an example? Ela Bhatt: Home-based workers, garment workers, bidi workers -- we have gone for demanding a higher wage rate, very often. We have had campaigns demanding for including garment stitching on the schedule of the Minimum Wage Act. Then for housing -- the bidi workers’ campaign for housing -- we often had to sit in front of the Urban Development Ministry. In Motion Magazine: How many people would be involved? Ela Bhatt: It depends. The number is no problem. I will tell you of a strike. Some time back we had a satyagraha of street vendors. We have a downtown market were the women and men sit with baskets of vegetables, fruits, and utility items. The market runs from the beginning of the day until late night and they are all our members, the women. The municipal corporation wanted to drive them out. We said that we have been here for the last three generations. It is our natural right to be here. Historically, we have been here. And it is true, they are the third or fourth generation that has been sitting there. But in the meantime, many new buildings have come up. And the shops have come up. And these vendors have literally been thrown to the street. They were being removed because they wanted to make a space for a parking lot. So, where was this taken? The police clamped on a curfew – a five days, six days curfew. The vendors started starving. They had nothing to fall back on. In the meantime, we had tried everything to explain our situation to the municipal corporation, to the police, everybody. But they didn’t listen to us. So, we said, in the most Gandhian way, that, “From tomorrow, 8 o’clock morning, we are going to sit here. Even if you don’t allow that, we are going to sit here.”

For about three days it went on like this. It was such good business because the vendors, they didn’t have to pay any fine to any inspector, or to the police -- fine or bribe, whatever you say. And in those three days, they didn’t have to have any stick beaten to them or their stuff thrown out on the ground. We managed ourselves. I was acting like a traffic police superintendent, managing the traffic. In Motion Magazine: What year was that? Ela Bhatt: ’89. And court cases, Supreme Court cases, high court cases – ninety-eight cases are now pending in the courts. We take the legal recourse in the court, also. But the base is negotiations. My experience and my colleagues’ experience has been that by going to the court, in the case of street vendors, yes, we achieved quite a lot, but in the case of home-based workers, piece-rate workers, you win the case but then the workers lose their job. The court may give an order to reinstate them, but the employers, I mean these are small employers who don’t forget. They don’t want such workers back again. While most of the cases were successful -- to raise the wage rate or to reinstate them -- the dispute was dealt with by negotiations, with face-to-face talk. Alternative economic organizations In Motion Magazine: So that they don’t lose their jobs? Ela Bhatt: Yes, that’s very important because in this country with all the unorganized sector labor, which is so much in surplus, there is always cheaper and more docile labor available. And these are women. It’s easy for them to suppress them. Also, the other strategy that we have, in rural areas particularly, you have to create, as a strategy, alternative economic organizations. You can’t go by typical trade union style. Even though agricultural workers are insured a minimum wage per day, a certain wage, with India’s overflowing labor supply there’s hardly any bargaining power in the hands of the laborer. You produce and sell in the market and when there is a balance of your own production unit, which is a cooperative, and you have a trade union demanding rights -- that joint action of union and cooperative is a good combination of struggle and constructive work to be able to obtain some bargaining power, to come in a bargaining position. That has been our experience all throughout. (For example) in rural areas -- these are agricultural laborers, landless -- they work for a few months of the year then they hardly have any work. (But when we found out that) their fathers, and their fathers, were weavers or potters we tried to revive those trades and formed a cooperative. And also, we had them go through a financial services bank to own cattle, so then they have some milk. In short, when there is more than one source of income, not only farm labor but also home-based production, something happening by way of craft, home-based, or agro-processing, whatever, and then thirdly dairy, when there is at least three sources of income, then they can with some comfort survive the year round.

Also, when we have organized many villages around, then the employer or the landlord cannot easily recruit labor from other villages because they are also part of SEWA. Full employment and self-reliance – social change In Motion Magazine: What are the basic principles of SEWA? Ela Bhatt: Our basic goals are full employment and self-reliance. Our own definition of full employment is full employment at the household level, not at the macro level. Such employment ensures full security -- income security and social security. In social security, at least healthcare, childcare, shelter, and insurance. SEWA has all these -- social security, our bank, the union, and the cooperative. Self-reliance is self-sufficiency financially, particularly I’m talking about their cooperatives, their unions. And then taking your own decisions so you are not just beneficiaries or users of the program but you are also manager and owner of the program. You decide and you manage in taking decisions, in managing your own affairs. You are self-sufficient. That is, in very specific terms, what we mean by self-reliance. The general philosophy is that of social change. The basic thing is against poverty. Poverty is a great disease and the country, SEWA, tries to go forward but poverty pulls it back all the time. There cannot be any excuse for not removing poverty. The priorities have to change. The resource allocations have to change. Policies have to change. The first priority is poverty removal and the second is maintaining the diversity, the diversity of our society. In Motion Magazine: What does that mean, specifically? Ela Bhatt: When different castes, different communities unite in SEWA or in a cooperative or in a union at the same time, they are able to maintain their own freedom to practice their own faith and their own culture. We don’t encourage total uniformity – though it’s easy. Literacy educationIn Motion Magazine: Do you do anything specifically related to education? Ela Bhatt: Education, if you mean by it literacy, then literacy has come at a later stage, only since five years back, because whenever we had consulted our members it was not on their priority list.

It was at their insistence that we started the literacy program. They have produced their own literature, in consultation with the new literates, and it’s going wonderfully well. We started with two districts, and now it is four districts. Now all the districts are demanding literacy education so we are planning, in a big way, a literacy program. Even old women, 80-year-old women, they come to the class. All over I have been observing women illiterates are very keen to learn. This 80-year-old woman, I asked her, “Why do you want to learn at this age?” and she said, “So that I can write ‘Ram’.” – God’s name. And her husband, he said that, “At night from her bed, you know what she does, she dips her finger in the water and on the wall she writes ‘Ram’. That’s how she practices.” I mean to say that the motivation is very high. In Motion Magazine: Is there a connection between democracy and economic involvement on this level? Ela Bhatt: Values are most important. Democratic values have to be instilled from childhood and the child sees at an early stage in life in every situation in society, in politics, in public life, in home life, what democratic values are being practiced. Whether you have money or not is not so much important. They are poor so they need enough to eat. They need to earn enough to eat and send the children to school, the basic needs. But just having more income does not make them democratic or make then concerned, feel concerned, about other people’s situations. You have to come together in an organized way in an organization which works democratically and on certain values. To serveIn Motion Magazine: And SEWA has those values? Ela Bhatt: Yes. Transparency. Never resort to any violence. Equality. Communal harmony. What does SEWA mean? “Sewa” means “to serve”. It’s a very pious word -- to serve others. The definition of “leader” in SEWA is “one who helps make others lead is a leader.” And that is why every three years we have elections, in a very systematic way. That is why we change leadership. And even in our unions when we fight with employers we never resort to anything that is a lie, untruth -- even if our members have made mistakes. Suppose a member has made a theft of a raw material or something, then we convince her to give it back. That way we are very particular. Look at the bank. If repayment has not come we record it that way. We don’t re-schedule the balance sheet so that you can show that you have 100 percent repayment, the way some make entries in such a way, and reschedule the loan account so that it shows 100 percent repayment. We never do that. It is no use because why should we do that? We are not merchant salt traders. We are not bankers, per se. We are in there for social change and in building the society, armed strong with human values. With more money or less money -- what character? It all depends upon character building and practicing democratic values. (At the national level), just to have, every five years, elections and to have your elected representatives sitting in the parliament or in the legislative assembly does not mean democracy. They behave in such an autocratic way. How in your daily life you serve others. How you think of others’ needs first before your needs. How you respect whoever is with you. That is why I see that the organizational union, the organizational cooperative -- these are two good, democratic, decentralized, member-based organizations of the actual producers, actual entrepreneurs. Changes in the garment industry In Motion Magazine: What do you see has been the impact of globalization on the women of SEWA?

And the demand is changing so fast. Let’s say SEWA Bank gives a loan for machines. Earlier, the old sewing machine was OK. Their sewing machine was 15 years old, but it worked. With the new kinds of products they need another machine. It is called full circle. Earlier it was half circle, half wheel. Now they need a full wheel. Then, they have to put on the electric motor to increase their productivity but also for certain designs. And they have to borrow again for the add-ons. By the time she is trained, or she is ready for (the new add-ons) manufacturing changes and another kind of add-on is needed. And the samples coming from Bombay, they are so secret. Because the infrastructure in the slums is so thin, electricity and other things, it becomes difficult for them to sustain the constant ‘other things’. This is the change we see in the garment industry. Globalization: the construction industry The construction industry also has changed very fast. Now that India is equipped to tender for global contracts and also now that India invites global companies for construction on big projects, the ordinary construction laborers are losing their chance of work. Young men who have gone through quick training they are now taking their place. Still, it’s a big country and everybody can’t afford those modern houses, so still there are opportunities in the area of rural housing. But, prefabricated walls and rooms, all this is already in the market and being used. In employment giving, next to agriculture is construction. It is the work for the landless labor from the rural areas, and 60 percent of them are women. They are losing their opportunities, existing employment opportunities. So, SEWA has now been training women construction workers in the modern skills for the last two years. Next month, we are going to have an international seminar on the skill upgradation of women construction workers and we are starting a school for women construction workers. Upgrading their skills for the future industry. In Motion Magazine: Is it hard to keep up? Ela Bhatt: It is hard to keep up. Embroidery, for example. In the desert areas, for them embroidery was just a part of culture. They embroidered for the dowry of the daughters. It was never for sale. Their main occupation had been animal breeding, some subsistence agriculture, and raising fodder for animals. Even milk was also a byproduct. But mainly it was animal husbandry. But because of the degeneration of the environment in those areas and the desert coming closer and closer to the district, they had to migrate with their families. Well, when the government brought the program for supplying piped water to these areas the women were not interested because what could they do with piped water. There was very little water underground. It was saline. And secondly, they can’t stay on the land for half of the year. So, SEWA was given (the job) to handle this program and we said that the basic problem is migration, and the migration has to stop. Unless we have employment at the doorstep, regular employment at the doorstep, only then will the migration stop. Only then will there be the interest. Unless the people themselves stay on the ground, they cannot regenerate the local ecology. It is they who are going to vivify their lands, not somebody from outside. So, after two and a half years, we identified that embroidery is a school in which we will build up the economy, the local economy. With a long struggle, and all that, embroidery has become a productive income-only activity for women. In the SEWA family, three generations in the family, women have worked with their hands. They average 800 to 2,000 rupees per month, regularly, even during the worst drought of the summer. Now, they have gone into the watershed area. They have built their houses earthquake proof, cyclone proof, because that’s a whole area prone to that.

And globalization has given us a very good opportunity to reach the global market. We have our website. Every day we get 10 to 12 queries out of which 8 queries are from abroad. We export. We have an export license. And the best of them, Raji, is being sold through orders from different countries. Only because we had an organization This has opened the gates to these desert women to the global market. There are opportunities but only because we had an organization which dealt (with them) in a very businesslike way. And we keep to the principle that any product if it sells for 100 rupees then 60 rupees has to go to the actual laborer, the producer, which is very difficult to maintain. But we have been able to maintain that principle. You can see that in five years time so much has changed. I don’t denounce globalization, totally. You can’t help it. It is there. It is going to come. We are not so powerful to stop it. But if you can get equipped … . The interests of the local producers The other thing is to represent the interests of the local producers at the different levels of decision making of globalization. If you are not organized, as SEWA is, then they will not have a voice or representation. We are on the committees on WTO (World Trade Organization). Actually, the government had asked us to be on the delegation but they didn’t provide the financial supports, so we can’t go. But the CII, the Confederation of Indian Industries, we work closely with them. Not necessarily everybody is against poor women and poor producers. They don’t know. They have hardly any information, knowledge of the grassroots, of what is happening and of their strengths. Similarly with farmers, small farmers -- our decision makers, our big industries, even agriculture, they have no idea. They have very little information, and whatever information they have is through their brokers, not from the workers, from the producers’ own voice. In Motion Magazine: So it’s a phenomenon that benefits those that have power, but if you create your own power then you can use it also? Ela Bhatt: It is not that they are not ready to listen. The CII, which has a lot to do with WTO and other globalizing policy, when we voice our constraints and our opportunities, all are not closed. That is how all these years we have learned to move, to make room for us, without a confrontation. In Motion Magazine: You computerized the bank not too long ago. I guess that fits in with what you were saying, using the technology that is available for your own purposes?

happening in faraway villages is online. The very next day its accounting -- of finance and raw materials -- has reached our office. Our own video -- a trained crew. Our best camera-person is a fruit vendor. Our best sound-recordist is an agricultural worker. The whole crew is from our members who earlier had never seen even a TV in their homes. Martha Stewart Communications from New York, she came and trained us and then she also trained us in editing and now sometimes we are on the TV. But mostly we use it for our own purpose. We have satellite communications (SatCom). The government of Gujarat has given, offers, the facility for a certain period of time during the month and the year to use the SatCom. Not I, but thirty of our organizers and members and leaders, are trained to hold meetings and discussions through SatCom. In Motion Magazine: It’s a seeming contradiction -- out of poverty the use of such technology. But there’s no reason not to? Ela Bhatt: Why not, why not? The poor have to have the best of whatever public resources are there. In Motion Magazine: So where do you see things going? It’s still a tough situation despite all your successes. Ela Bhatt: There’s nothing like success. With one success to another challenge there is a bond, at the same time. There is nothing like success and nothing like failure. In failure new opportunities come up, and you see some really worthwhile happenings in those failures. It is an ongoing process. I think what is important is a woman’s own self-confidence, women’s own confidence in themselves. That we can do it. Then we will do it. When you are together you don’t cry. We don’t blame the destiny. We don’t blame the system. We are togetherness and have faith in each other and in ourselves.Life is never without difficulty, without struggles. As we learn, dealing with these difficulties, we manage our own affairs, at the family or at the committee level, or at the organizational level, or at the board level. I firmly believe that that is a process of empowerment. Working yourself, and dealing with your own affairs yourself, that is an empowering process. It is an ongoing process which never ends. In Motion Magazine: How much social change can there be?

At the same time, we are also conscious that we are not that powerful to stop globalization or to stop the India-Pakistan war, to stop nuclear war -- the same. We are aware of other limitations as well. But, at whatever level we are at we are changing the balance of power in favor of the poor and women. One step is enough. Step by step. Also see:

Published in In Motion Magazine December 18, 2003 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2018 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||