|

Interview with Yin Shao Loong

of Third World Network Democracy at the International Level Johannesburg, South Africa

Yin Shao Loong is a research officer with the Third World Network. The Third World Network is based in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. This interview was conducted September 3, 2002 by Nic Paget-Clarke for In Motion Magazine during the United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, South Africa.

In Motion Magazine: Can you tell me a little bit about the Third World Network. Yin Shao Loong: The Third World Network operates as a network of groups and individuals from all over the world with a special emphasis on advancing developing-country issues on environment and development, which in this particular place, Johannesburg, we should call sustainable development. It was founded in 1984 out of an international conference in Malaysia from a large number of grassroots groups, academics, activists, and so forth who saw the need to develop a more international presence from local campaigns. It was increasingly clear that many issues in development politics and environmental crises required an international-level response, which was beyond the capacity of most local groups. It was therefore decided that some sort of international organization would be needed to service these interests. We are not a membership organization, although some of our network people are membership organizations. We are a group of like-minded people and groups. We have secretariats in Africa and Latin America who do their own regional coordination, as well. Everyone is quite autonomous. We work with a range of people. In Motion Magazine: Can you mention the names of some of the member organizations? Yin Shao Loong: We tend to work with more quiet grassroots groups such as the Project of Ecological Recovery in Thailand, for example. We work with the Sunshine Project who work on bio-weapons control.

Yin Shao Loong: Agenda 21 has suffered greatly since 1992, in Rio. It was an important advance because it linked the growing sense that some kind of action did need to be taken on the environment and global environmental crises as well as the individual local crises, which collectively represents a global environmental crisis. It also recognized that there was a development crisis in the Third World, in particular, and that that needed to be addressed. It recognized that there was a great tension in pushing an environmental agenda which was shaped largely as a discourse from Northern environmental groups, in sense of conservation, in some ways on the Greenhouse Effect as well, but which didn’t really put people at the heart of the vision. What was important about Rio was that it integrated people in the environment together with the concept of sustainable development. It tried not to sacrifice one for the other. It didn’t say, "No development and be happy living in a perfect environment," which is a fallacy anyway. At the same time, it didn’t say, "Have development or industrial development and sacrifice your environment" because it will come back to haunt you. It provided an important linkage between environment and development, which rightly should have taken root in terms of international policies around the world. But, because of the strong advance of the economic globalization agenda that (linkage) never happened. That sort of framework of sustainable development had a very important concept for equity at its heart, of "common but differentiated responsibilities", as one of the Rio principles is known. That the rich countries and the poor countries should work together, with the rich helping the poor collectively to ensure sustainable development in all places. But the rich countries, and those who aspire to be rich countries, threw all their energy into pursuing economic globalization. The foundation of the World Trade Organization (WTO), in 1994, was a clear example of that commitment. Also, is the way that the WTO has been contorted to serve the interests of the largest economic powers. The mercantile interests have predominated over considerations of broadly sustainable development -- economic, social and environmental. It’s been the economic, overall, that has come through. In Motion Magazine: Is that what is meant by the crisis of implementation? Yin Shao Loong: Yes. There is a crisis of implementation because it never really got implemented. There was local Agenda 21, and so forth, and there were attempts to pursue sustainable development. But it doesn’t really survive in isolated pockets, as it struggles to do today, if it is being swamped by the old form of development, which sustainable development rose up in response to. People are finding that industrial development or industrial-style development isn’t really working. For many countries, going to manufacturing couldn’t be sustained because of, say, structural adjustment polices imposed by the World Bank.

In other areas, industrial agriculture was proving to be a flawed model, in terms of the impacts on people’s health and also on the environment, of using toxic agro-chemicals, of having an inputs-in-production-based form of agriculture rather than a needs-based and distributive form of agricultural policy. In Motion Magazine: What do you mean de-industrialize? How did that happen? Yin Shao Loong: The structural adjustment policies have been quite crushing in terms of debt, so a lot of African countries weren’t able to sustain their industries and a lot of industries have collapsed -- partly through dumping of imported goods. For example, Zambia once had a thriving textile industry and that industry has collapsed -- in large part due to the financial crises that have gone on in that country and also by the dumping of cheap textile products from developed countries which undercut the whole market for local producers. So they’ve fallen on hard times. A similar case happened in the area of agriculture, where cheap food is dumped in developing countries and local producers can’t compete with heavily-subsidized food. This is why, for example, agricultural subsidies are a big issue at the summit, and at many other international forums, as well, because the amount -- what is it, $130 billion -- which President Bush has promised to American farmers? Similarly, the billions of Euros that the Common Agricultural Policy underwrites in Europe don’t leave a level playing field. Farmers in poorer countries can’t compete with that. It’s impossible for them to mobilize enough resources to meet the cheaper price of those goods. Low commodity prices: price makers, price takers In Motion Magazine: That’s tied in to the low commodity prices? Yin Shao Loong: It’s tied in to low commodity prices. And part of the low commodity prices issue is also the abandonment by Reagan and Thatcher in the ’80s of a commodity price-fixing system, as well. In Motion Magazine: Why did the local commodity prices drop? Yin Shao Loong: Because it wasn’t an overall agreement to sustain commodity prices between both the people who had the power, say the U.S. and Europe, and developing countries, which are commodity producers. There wasn’t a joint agreement that people would agree for the benefit of those commodities produced that price should be sustained and maintained at a fair and stable level. And the developing countries weren’t powerful enough on their own to set up a price-fixing system. They were too crushed by foreign policy pressure, by debt, as I said before, and by a lot of readjustment factors as well. If you take the example of OPEC, which is a clear example of a group of commodity producers who have allied together to try and control the price of their commodity and the stability of that price, a clear example of how a commodity price-fixing system can be made to work in the benefit of commodity producers, they become price makers as the economics goes.

In Motion Magazine: When you say commodity - that means natural resources … ? Yin Shao Loong: Primary commodities. And, at the same time, for a lot of developing countries that have gone into manufacturing, as in manufacturing semiconductors, what studies are finding now at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, based in Geneva, UNCTAD, they are finding that even secondary and tertiary commodities like semiconductors are behaving like primary commodities. They are fluctuating, as well. There’s no guarantee that jobs will stay. Investment capital can shift from Malaysia to Korea to Mexico to China, and so forth, depending on what kind of price they can get for labor. What kind of subsidies they can get for investment in their tax breaks, for example, the ten-year tax breaks, twenty-year tax breaks, discounts on land purchase designed to entice investment. That creates a lot of instability in terms of employment, and also development in any particular developing country that is a labor provider for the manufacturing of these products. And obviously that has consequences on the environment, as well, because you build up new factories, you site certain types of production, and then that production doesn’t have any continuity. Overall, worldwide, you have this effect developing where land gets industrialized but then there’s no kind of regenerative capacity when investment leaves. People may move from rural livelihoods into the urban environment to take up wage labor jobs in factories. If those jobs vanish, then it’s very hard to go back to the rural environment and re-start life there because those skills easily vanish after a short time. At the same time, if you don’t have any other wage labor alternatives then you get the problem of urban poverty, as well. Tight bilateral trade agreements vs. sovereignty of national policy In Motion Magazine: Is that a mechanism of transferring wealth from the Third World? Yin Shao Loong: One of many. In Motion Magazine: What are some of the others? Yin Shao Loong: Broadly put, you can say the declining terms of trade which may involve the enforcement of very tight bilateral trade agreements, such as a host government agreeing that if an investment fails to come to fruit, or if a country decides to terminate an investment of a company for whatever reason, then the company may decide to sue the government for future profits not earned. This is a very dangerous concept because one, you have to try and fix the price of what potential future profits you may have earned given all other factors, and, two, it denies a proper place for sovereignty of national policy to decide that, well, we have decided that this investment is not conducive for our country. We would like to shift, for example, or the privatization of certain resources has not worked and we would like to stop it and renationalize. It gives an incredible amount of power to a private company to sue an entire nation for damages.

The Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI) returns Similar host-country government agreements operate in Turkey on oil pipelines, in Chad and Cameroon on oil pipelines. Many mining companies also operate miniature versions of that with many governments around the world, as well. And a lot of this is very similar to what was proposed several years ago in the Multilateral Agreement on Investment, the MAI, proposed within the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) framework, which many, many civil society groups protested about and managed to bring to the light. There was a massive public campaign around the world and negotiations on that deal were stopped successfully. Unfortunately, this same concept has now gone into the WTO and it’s one of the new issues that is up for consideration and negotiation at the meeting in Cancun, in Mexico, next year (2003). This is something that the multinational corporations really desperately want and they will try and get it in whatever forum they can. They will try and push it ahead because it gives them an incredible amount of power to set the terms of their trade, of their earning, of their investment, and so forth. It disempowers sovereign states, at the end of the day. It disempowers people, at the end of the day, because it doesn’t give any power to governments, democratically elected or not, to adjudicate in the favor of national interest. Hot money, capital flight, tax havens In Motion Magazine: What about financial liberalization, changing banking laws so that they can bring in hot money? Is that another method? Yin Shao Loong: Yes, hot money is another method. Capital flight is a big problem; the proliferation of offshore banking sites, tax havens. The many island countries, which are tax havens, are a big problem. It’s a big problem -- money traveling out of countries. Investment may go in, but does it stay at home? In Motion Magazine: What puts countries in the position that they liberalize their financial laws? Yin Shao Loong: It varies from country to country, but you may have a position where a country may be in fiscal crisis. You’ve got an incredible amount of demand from foreign investors. You’ve got diplomatic pressure from capitals like Washington, for example, to open up in favor of those investors. You may already have existing foreign debt which you have to repay, and one of the conditions for repayment may be the liberalization of your financial sector. And the IMF (International Monetary Fund) carries a certain clout. Whether people are wise to the problems, or not, if you are in a position as a civil servant of a country, even a developing country, and the IMF comes along and sends its delegation there’s a certain position of power that they have in terms of financial leverage on your decision-making, and also their status as an international organization. Because the IMF and the World Bank are both donor driven, the people who sit on the board, the main donor countries, are those who end up shaping the policies of the IMF. And those are the countries which are the home bases for many of the world’s largest transnational organizations, as well. So you get the one-dollar one-vote dynamic and that money, and the existing debt that the IMF and the Bank encouraged many developing countries to take on in the ’50s and ’60s and ’70s, is being used to basically crush the decision-making power of those countries. Many countries are paying more on debt servicing than they are on health and education. For example, in Indonesia every Indonesian person effectively pays 45 U.S. dollars a day on debt servicing and they receive roughly two dollars a day in terms of education and health. And the largest creditor to Indonesia is Japan. That credit is largely in the form of private sector debt, private sector credit to Indonesia. Even the Japanese government is reluctant to make any further move on debt relief because it doesn’t want to interfere with its corporations. At the end of the day, you have a couple of private companies holding the world’s third largest nation hostage. Corporations at the U.N. Summit

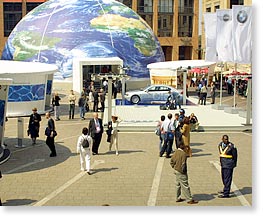

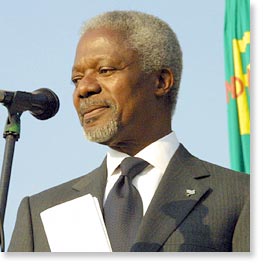

Yin Shao Loong: Sometimes quite crudely and sometimes quite subtly. Crudely put would be the BMW exhibit in the middle of Sandton Square or the BMW adverts on “clean energy” three feet out of the door of the plane as most people saw when they got here. Although the last I heard they are a car company. It’s what a lot of people call “greenwash.” There’s a lot of that conspicuously present. And large delegations of business people are within Johannesburg, as well. They held their own big business conference the other day. They have been invited in terms of pride of place, in terms of several events, as well. But in many ways, big business doesn’t really need to promote itself too strongly because it’s done the job. It’s already ideologically captured many people within the U.N. and within governments, but more so the U.N. than governments. I mean, Kofi Annan has embraced big business. He has a great frustration with governments, the slow decision-making of governments, and he believes that multinational, big business can move faster and further and better than governments, in terms of delivering development. On Sunday, he made a call to business leaders to boldly go where angels fear to tread. He believes that big business can deliver development for the world where governments cannot, which in its own way is a weak response. It’s correct to feel frustration in terms of the U.N.’s position vis-à-vis the bottlenecks in international geopolitics and the power dynamics where the large states can block the efforts of small states, particularly within the forums like the United Nations, but at the same time it’s a grievous error to assume that those agents which are relatively free of that form of blockage from the large states, namely transnational corporations, are therefore the best agents of delivery. Just because capital is free to move doesn’t mean that capital necessarily delivers development. And capital, in the form that we presently see it, in terms of hot money, speculative currencies, in terms of the investments, and the nature of the investments I’ve just described, as well -- it’s a mistake to believe that. Many people are calling for rules and regulation on transnational business rather than having more free trade because in many ways the way transnational business operates is to play off countries against each other, is to take advantage of the lack of democratic structures in some places, provisions in all countries, not just in developing countries but also in developed countries, to get hold of the resources that they want on the terms that best favor them at the lower price possible.

Democracy at the international level The major problem that we are facing is not that there is a lack of democracy in some developing countries, which is the good governance debate which is bandied about by both transnational corporations and Northern governments, but the fact that democracy doesn’t really operate at the international level, such as in organizations like the IMF and the World Bank who hold hostage a large number of countries. It is hypocritical for those countries which practice democracy nationally and don’t practice it internationally to make that sort of demand on other countries while they are holding the reins of power.In many cases, a lot of the demands for good governance aren’t for better treatment of citizens. They are often couched in terms of human rights, but quite vaguely so. Rather, quite specifically, I’ve heard governments and companies mention, when they are talking of good governance, the enforceability of contracts -- the rule of law. It’s not the rule of law in defense of the common person or in defense of the marginalized minorities, as many human rights advocates would call for, but it’s rule of law in favor of those who have investment capital. In Motion Magazine: In what way, for example? Yin Shao Loong: If a company decides to embark on a host government agreement, like I just described, whereby, "If our investment fails or for some other reason we are asked to leave the country, then you will compensate us for a figure that we propose that would have been our full earnings for this investment." In Motion Magazine: Or intellectual property rights? Yin Shao Loong: Or intellectual property rights, for example. Or, "You will agree to effectively cede control of this portion of your national territory over to us by giving us a contract for mining and exploration in that area,” and “You will agree to provide a portion of security forces to guard our compounds, etc, etc, and in return we will give you this amount of money for your national military budget," and so forth. In Motion Magazine: What’s an example of that? Yin Shao Loong: Indonesia would be an example. The mining company Rio Tinto and Freeport McMoRan, they are partners in Indonesia. They provide 20 percent of the Indonesian military’s national budget. Which is crucial for doing their business because they tend to do their business, they tend to do their mining, in areas where there is a lot of civic conflict. And mining itself produces a lot of civic conflict. The Freeport mining is taking place in West Papua where there is a civil war going on and the Freeport compounds are guarded by the Indonesian military. Or rather more conveniently, as they say, the Indonesian military makes requests to have a small base located on the site of the mining area in which they can wage war against the insurgents. But, really, it’s hard to say what’s waging war against the insurgents versus protecting the mine from people displaced from the mining area who may become insurgents, at the end of the day, to try and recapture their lost land. And Henry Kissinger is on the board of Freeport McMoRan, as well. He helped them secure many favorable deals back in the ’70s. In foreign policy, revolving doors between government and big business, and complicity of transnational corporations in military atrocities, it’s business as usual for them. This is why regulation is needed, not more free trade. That’s why things like the power of these kind of investment agreements has to be stopped.

Yin Shao Loong: Friends of the Earth is one of the groups involved in the push for corporate responsibility. There are many, many groups around this. CorpWatch, Groundwork. Greenpeace, as well, is pushing for it. We’re pushing for it. Many, many, many groups and many people have been calling for stringent regulations of corporations for many, many years. In Motion Magazine: How’s that going? Yin Shao Loong: I think it’s going well. The movement is strong because the need has been there. The demand has been there for decades, really. It’s intensifying even more as the corporations push harder and harder and harder to every crevice of life on the planet. In Motion Magazine: How would they be regulated? Yin Shao Loong: There’s a lot of existing regulations which haven’t been implemented, such as standards on toxic chemical emissions, standards of corporate conduct, labor provisions, social security provisions, liability for damages both to people and the environment. There are many, many of these rules that can be played. There can be regulation on flows of capital, in and out of a country. There can be regulations which allow a company, which operates subsidiaries in many countries, for the headquarters to be sued and not necessarily the subsidiary. In many cases, the subsidiary, say, is operating in Namibia, and for someone in Namibia to pursue justice against that company, which is a subsidiary of a large company based in London, it may be very difficult to find that justice in a Namibia court. Whereas to try and pursue it in a British court -- you may be able to get sufficient damages to deter that kind of company and also get sufficient re-compensation for the damages caused to your health. (I’m speaking here of) a case of uranium mining in Namibia. But, in many cases, subsidiaries are designed to have very little cash left so if they are sued for liability there’s almost nothing that can be given to the communities affected. … That process of piercing the corporate veil, as it is known, has proved to be very difficult. Judges in the United Kingdom have thrown such cases out of court because they thought they may deter multinational companies from headquartering in the U.K., and it would be a precedent set if those companies could be sued within the U.K. for activities conducted overseas. You already see within developed countries a soft corruption going on, even within the judiciary, by big business. Just from the sheer promise of its investment in the country. In Motion Magazine: What does transparency mean in that context? Yin Shao Loong: Transparency depends on who is talking and who has the power to act upon transparency. Transparency is access to information, basically. For campaigners working on toxics, for example, transparency can be good because you may then find out who is the real owner of the company that has been dumping toxins in your back yard, into your lungs, into your kids and so forth. Transparency may allow you to see the structures of ownership, of financial ownership, and then pursue justice at the top. But on the other hand, companies are making demands for transparency in countries, particularly developing countries. They are trying to push this through the WTO in order to see how investments are made and then from that point on, having that information, they can then make further demands for liberalization of a particular sector if they see that there’s a large amount of cash flow in a particular good or service that a government is doing. They could, then, put in a request for liberalization after the transparency agreement has been procured. Transparency may be a step towards a stronger investment agreement because then countries can bring in their political and financial muscle to force a weaker country to liberalize in a particular sector. There are already demands for government procurement to become an investment issue within the World Trade Organization, such that governments cannot choose if they want to procure a service or product. They can’t favor a domestic company over a foreign company. If you want to buy pencils, for example, you can’t choose your own small or medium industry. You might have to give (the contract) to Faber-Castell -- if Faber-Castell, for example, comes in and demands to be treated in the same way. If there’s such an agreement enshrined into international law, they can sue. That company can sue that government or ask a government that wants to sue on its behalf to sue another government. It could ask its home country government, Germany, for example, where Faber Castell is based, to sue Malawi for purchasing pencils. For purchasing pencils from a small or medium enterprise. It can say that you cannot discriminate in favor of a small or medium enterprise because there’s a national treatment principle that applies on government procurement that we should all be treated the same. It’s a level playing field. But if you’ve got a level playing field where one person is a ten foot giant and the other person is a three-foot midget, that’s not a level playing field at all. A level playing field should tilt the playing field such that both the midget and the giant are standing at roughly the same height. These are not existing agreements, but there’s a huge push within the WTO by countries like the E.U. (European Union), by the U.S., by Japan, by Canada, and Australia for such agreements to be put in place because it favors them. Because they have the economic muscle to make such an agreement work in their favor. And it’s opposed by developing countries because they can’t possibly compete. Their national industries will be destroyed. Domestic industries, or small producers, small farmers for example, will be destroyed by this kind of investment. Yin Shao Loong: It’s not the only forum. In terms of the broad mandate and the democratic provisions within it, the U.N. is a good forum on paper. In terms of its power dynamics, the U.N. has been severely weakened by being held hostage by donors, donor boycotts, basically. A powerful country may choose to withhold funding from the U.N., in terms of agreements, and that kind of action holds an international institution like the U.N. hostage, desperately so. There hasn’t been sufficient movement on trying to free up the U.N. from that kind of power relation. In Motion Magazine: That would be the reasoning behind the U.S. not paying its dues? Yin Shao Loong: Yes. In Motion Magazine: It wasn’t just over birth control? Yin Shao Loong: No. And there are many other ways to hold the U.N. hostage. And that’s why the U.N., say the Secretary General, has run to big business. Because many agencies are so strapped for funds that they are in a position where they see there is money in big business. But whether they can actually get that money is another question. They have nowhere else to go. If a publicly-funded agency cannot source funds then the public-private partnership seems increasingly attractive. Whether it actually fulfills the agency, at the end of the day, is absolutely another question. Because that money comes with conditionalities. Unilateralism vs. Multilateralism In Motion Magazine: How do you see this in the context of the global “war on terror”? Are they related? Yin Shao Loong: Well, it is in there’s a sense that there is a common thread of unilateralism that rides between the two and a common thread of bilateral coercion and ad hoc alliance building. In many ways, the so-called “war on terror”, or the so-called “phenomenon of terrorism,” is a direct product of the aggressive foreign policy that the U.S. has pursued over the last between fifty to a hundred years, and also it is a consequence of many states pursuing similar such policies on their own national or regional level, as well. Terrorism has had such a fluid definition over the last year. What is a liberation struggle or insurgency in (any number) of countries suddenly gets redefined as terrorism because it nominally fights against a state. Whether that state is right or just in its pursuit of its interests is another question, but the terrorism dynamic tends to walk on a state versus non-state actor basis. It accords all legitimacy to the state and none to the non-state actor, unless, of course, the non-state actor is acting in your favor. The U.S. has funded so many counter-insurgency struggles and counter-insurgency struggles in so many countries over many years, it’s convenient now to forget that and see the U.S. as an embattled country. The way the U.S. is using the opportunity to re-militarize the rest of the world is quite alarming. Multilateral: the U.N., the WTO In Motion Magazine: Could you sum up what has been going on here at the conference? Yin Shao Loong: What we’ve seen at the conference is, broadly speaking, the death throes of the United Nations multilateral system. The process hasn’t worked because the multilateralism system is supposed to balance power between the big and the small. It hasn’t worked here for a number of reasons. One, because the big are too powerful and they have too much influence in shaping the outcomes of the multilateral forum. Two, because many of the medium-sized players are caught up in the agenda of the larger actors and they too, for example, wish to pursue trade over the environment. Many countries consider the WTO to be a more secure forum than the United Nations for pursuing their interests because many have an unreasonable fear of the environment, that it may be used as a condition for sanctions against them by larger countries. But, not a (completely) un-founded fear because such things have been done in the past. That’s the reason why many developing countries joined the WTO, even though many decry it now as a very evil or unfair institution. The alternative for them was far, far worse -- that they would be left out in the cold having to negotiate with bilateral trade pressure with the U.S. and other large trading blocks, without a rules-based system. Many developing countries thought it was better to join the WTO, to submit to that organization, rather than to be cornered alone with the large trading blocks. In many ways, that decision has affected how these countries operate within the U.N. They are so afraid of getting crushed in the trade agenda that they aren’t able to pursue the sustainable development agenda. Many key areas, as well, are stuck in a way which a multilateral negotiation cannot resolve -- like energy. The OPEC countries, oil-producing countries, and those countries facing climate change, threats, for example, aren’t able to resolve their issues properly within this multilateral forum because a consensus-building negotiation isn’t really possible to resolve the very complex issue of world energy. It will take something far more complex and more inventive than a multilateral forum to resolve the issue of energy -- how that can be worked out, how greenhouse emissions can be cut -- than trying to simply push getting countries to agree to renewable energy. That simplifies the range of political interests at stake, simply saying that renewable energy can replace fossil fuel energy. How are you going to tell an oil producing country to switch over to renewable energy if it’s a developing country, which in many cases they are, and they can’t afford to get that technology and the technology transfers promised at Rio were never delivered over the many years? It leaves no alternative.

In some ways, multilateral fora are both a product of their own framework and also a product of the kind of actors that come to the table within it, as well, and the power interests being played out. In Motion Magazine: Do you think the administration of the earth is shifting from the U.N. to the WTO? Is that what you are saying?Yin Shao Loong: No, I wouldn’t say that. I would say on issues of trade and environment the WTO has a lot more strength for a lot of reasons. Because it’s legally binding. Because it’s the hot issue, at the moment, and trade is the primary interest of the world largest countries. They are using all their power to pursue that agenda within the World Trade Organization. But at the same time, it’s good for political play to say that the WTO is taking over the U.N., and to a certain extent some of that is true, but it’s not just the WTO because you already have institutions like the IMF and the World Bank. You’ve got bodies like the OECD. You’ve got the G8, for example, to which a lot of economic decision-making for global economic affairs has shifted. And the G8 is not a democratic forum. It’s only eight countries who set the economic agenda for the world. Which is why African leaders like Thabo Mbeki travel to Canada to plead to the G8 for money, or plead for African development. A person coming begging at the door like that doesn’t have any power.

It’s a complex international arena that operates on many levels but it’s not just nation-states, of course, it’s civil society, as well. How civil society mobilizes and organizes to meet that challenge to try and help balance the power between states, and between the interests of states and private corporations and the interests of people, is going to be our political landscape for the next century and onwards. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Published in In Motion Magazine, June 21, 2003 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2018 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||