|

Changing Course to Secure Farmer Livelihoods Worldwide Executive Summary by Daryll Ray, Daniel De La Torre Ugarte, Kelly Tiller Agricultural Policy Analysis Center The University of Tennessee Knoxville, Tennessee

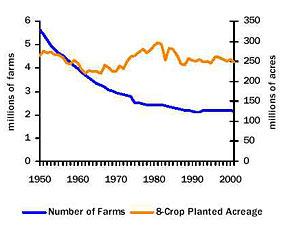

Perhaps at no other time in history has so much attention from outside the United States been focused on what is ostensibly a domestic matter -- U.S. agricultural policy. And with good cause. Since the late 1980s, but particularly since 1996, the U.S. government’s official policy has been to permit, even encourage, a free fall in domestic farm prices while simultaneously promoting rapid liberal trade measures to open new markets for U.S. products. U.S. farmers, the intended beneficiaries of these policies, have languished, despite official rhetoric to the contrary. Meanwhile, major agribusinesses have thrived, while aggregate U.S. exports remained flat, and farmer income from the marketplace declined dramatically. The precipitous decline in prices of primary commodities, especially grains, is providing agribusiness and corporate livestock producers access to agricultural commodities at below the cost of production, consolidating their control over the entire production and marketing chain. (1) Plummeting world prices have followed the U.S. lead, where prices of primary agricultural exports (corn, wheat, soybeans, cotton, and rice) declined by more than 40 percent since 1996. U.S. farmers continue to be forced off the land despite a massive infusion of government payments intended to compensate for lower prices. The impact on farmers in other countries has been even more devastating. From Haiti to Burkina Faso, the Philippines to Peru, these unprecedented low prices have destroyed livelihoods and reaped a harvest of desperation, hunger, and migration.Solutions to this alarming predicament for the world's farmers depend entirely on how one interprets and understands the responses to two key questions: How do farmers' planting decisions respond to price signals? How do their domestic and export customers respond to price signals? In answering these questions, this paper demonstrates that, in the aggregate, neither crop supply nor crop demand is very responsive to changes in price. A thorough analysis of the historical data on U.S. policy and its influence reveals the truth of what impact that policy has had on farmer incomes. Farmers have tended to respond by doing what they know best: plant and produce more food, guaranteeing their continued financial distress. Clearly, stopping this cycle requires more than most critics of U.S. policy suggest: that merely eliminating direct payments to farmers will help in the quest to raise farmer incomes via the market. Instead, a thoughtful examination shows conclusively that government must play a major role in helping to manage excess capacity if prices are to be held within a band that is reasonable for both producers and consumers. Government policy must continue to keep the engine of the agricultural train running ever more efficiently through its investment in research, extension, technology, credit and marketing, but it must also be willing to slow down the train through the careful and judicious application of a variety of policy tools, many of which were abandoned in the 1990s. U.S. policy makers bear much of the responsibility for bringing about the alarming conditions facing world agriculture today. So it is obvious that policy makers must respond with fresh thinking and a willingness to consider alternative approaches. This paper explores alternative scenarios for the future, based on simulations of policy instruments and their impacts on prices and production levels. Finally, it offers a blueprint of policy options that enhances farmer livelihoods in the U.S. and around the world. Efforts to decipher the causes of the present crisis have cast a spotlight on one of the U.S.’s most visible and, for most, egregious examples of hypocrisy and double-speak: the extremely high level of U.S. government payments to farmers while simultaneously encouraging other countries to reduce domestic agricultural supports. Although these payments have technically fallen within our support reduction commitments under the World Trade Organization (WTO), they have risen dramatically since 1996 and stand as a testament to U.S. admonitions to “do as I say, not as I do,” when it comes to trade liberalization. The severe drop in farm income that would have occurred in the absence of this compensation has been cushioned by these payments, which exceeded $20 billion annually for the last several years. Lacking comparable support from their own governments, farmers in the developing world find themselves experiencing the full force of the price reductions. Meanwhile, farmers in other subsidizing countries, such as the European Union (EU), complain that the U.S. policies amount to unfair trade advantages. Negotiations within the WTO to come to a common Agreement on Agriculture are completely bogged down as a result, with positions hardened on all sides. While specifics may differ, many point accusingly at the U.S. for what are perceived as serious violations of the principles of free trade in agriculture. How Did We Get Here? Policy Choices Dictate Prices and Payments The crisis agriculture faces today is no accident. It is the direct result of expanding productive capacity while ignoring the need for policies to manage the use of that capacity. U.S. officials replaced mechanisms for supporting prices and managing aggregate supply with a sudden preference for an unregulated free market. The outcome has been disastrous but predictable. U.S. farm policy removed set-asides, crop reserves, and price support tools, leaving no way to deal with low prices, except for emergency government payments to compensate for farmer income losses. As price supports were phased out and eventually replaced with marketing loans and income support payments, crop prices tumbled to depths not seen since the 1970s. Even when crop stock levels diminished, tighter market conditions did not lead to normally predictable higher prices. This would be a red flag in any industry, and it is an indication of the significant dangers that current U.S. policy has created. Long-standing expectations about just how low prices could be driven are now in question, with no real bottom in sight and thus, no pressure to drive up prices despite tight world supply. Many agricultural experts feel that the extraordinary agribusiness consolidation now occurring has discouraged the normal price increases that would accompany tight supplies. Finally, U.S. pressure to open new markets resulted in the removal of tariffs and quotas protecting price levels in fragile agricultural sectors throughout the developing world. Dumping of U.S. products increased along with a chorus of voices claiming unfair trade practices. A recent (2003) paper from the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy estimates that dumping levels, or the extent to which the export price is below the actual cost of production, are astounding: 25 to 30 percent for corn, 40 percent for wheat and an unconscionable 57 percent for cotton. (2) Less understood is the complex relationship between subsidies and prices. Subsidies are U.S. government payments made directly to producers. Most critics of these payments, which nearly tripled since the key turning point of 1996, point to their role in increasing production, thereby glutting the market and forcing prices lower. Instead, this study provides evidence to show that the relationship is far from a linear one, with the reality far more complex than many would have us believe. U.S. production of the eight major crops (3) increased as land previously idled by government set-aside programs was brought back on-line. In the absence of traditional supply management and price support tools, prices declined sharply. Faced with drastic impacts on net farm income, the U.S. government responded by paying farmers compensatory sums to help close the gap. These payments began as so-called “emergency payments,” in response to the first market shock in the late 1990s. By 2002, it had become clear that farmers and the rural banking sector would not be able to survive on incomes derived solely from the market. Direct payments decoupled from planting and production decisions were reinstated. Additional direct payments are automatically triggered as prices decline, so that subsidies are both fixed and automatic. If this practice does not change, one can expect U.S. government outlays for farm programs over the next ten years (2003 to 2012) to exceed $247 billion. (4) Consolidation Aided by U.S. Payments and Low Prices Yet even with these enormous sums being pumped into the system, farmers are failing. For many, the payments do not close the gap between the cost of production and the market price, and the distribution patterns only reinforce the long-standing bias in U.S. agriculture for bigger, less diversified farms. U.S.DA figures show, for example, that between 1993 and 2000, the U.S. lost nearly 33,000 farms with annual sales under $100,000. (5) Some might argue that, painful as it is, these “adjustments” to the market are essential to re-balance supply and demand in U.S. agriculture. This is simply not so. The number of farms and farmers continues to decline, but the amount of cropland in production remains relatively constant, as seen in Figure 1. New production technologies are increasing productivity on those cropland acres, further expanding production. The unchecked continuation of this trend will surely result in an agriculture dominated almost exclusively by large, highlymechanized farms planted fencerow to fencerow with the scant selection of crops such operations produce best: corn, wheat, rice, cotton and soybeans. In other words, the policies of the 1990s accelerated the changes in the composition of our farm sector and the degree of its consolidation (including within agribusiness). Diversified, independent, owneroperated farms are rapidly disappearing, as seen in Figure 1. Many of the remaining small farms may well be controlled by large agribusiness firms through contract production. Such a future spells ruin for farmdependent rural communities and small and moderate-size farms within the U.S. and around the world. The future is especially grim for the 2.5 billion people in developing countries who depend on agriculture for their livelihoods. Continued access to markets and fair prices for their products means the difference between sustainable livelihoods and disaster. Eliminating U.S. Subsidies is Not Enough The elimination of domestic subsidies is the key issue dominating international negotiations on U.S. agricultural policy. While some in the European Union or Cairns Group countries demand an end to U.S. subsidies as a point of fairness or to equalize perceived market advantage, the developing world seeks an end to these subsidies as a point of survival. The goal, well beyond that of merely ending direct payments to U.S. farmers, is to restore a measure of sustainability for the world’s poorest farmers for whom receiving better prices --that is, fairer prices --in the marketplace is absolutely critical. One seemingly rational theory is that the elimination of subsidies will force U.S. farmers to confront the disciplines of the market and respond. It is thought that once the cushion of subsidies is removed, the market will force a reduction in U.S. supplies and a subsequent price increase. Just as low U.S. prices have been transmitted around the world, so would the higher prices, ultimately benefiting agriculturally-dependent countries throughout the world. However, two separate models testing this scenario reveal a surprising outcome. The removal of subsidies, while causing significant repercussions for farmer income in the U.S., would not reduce overall U.S. production in a timely fashion or result in substantially higher prices either domestically or on the world market. While prices for cereals in particular would rise over time, the magnitude of the rise (only three percent by the year 2020) means this option does not represent any reasonable or timely improvement for the livelihoods of the world’s poorest farmers. Turning to the U.S., the consequences of instituting such a policy change are so dramatic that this option is not likely ever to have real political viability in its most absolute form. The drastic reduction of between $11 and $15 billion in net farm income from the average of $48 billion projected under present policies would have enormous repercussions for the rural banking system and, more broadly, for rural economies. This loss of between 25 and 30 percent of net farm income would result directly from the elimination of direct government payments, and crop producers would bear a disproportionately large portion of the drop in income. The decline in income would occur at a time when many feel U.S. agriculture is already in crisis. Under the more likely scenario of staged reductions in payments, net farm income continues to drop, largely because of the fundamental inability of the sector to selfcorrect in time. Even in an environment of chronically low prices and farm income, farmlands do tend to stay in production, and aggregate production does not decline enough to drive up prices in any appreciable sense. There would, however, be some adjustments in the mix of crops planted, with cotton and rice losing ground to corn, wheat and soybeans. Some advantages would accrue to cotton and rice farmers in competing countries by reason of the reduced exports in these U.S. crops, but this benefit would not likely persist for long. After a portion of the land in other countries is switched to cotton or rice in response to higher prices, prices would again face downward pressure. Blueprint of a Workable Alternative No one policy instrument can be said at this point to hold the key to resolving today’s crisis, though several tool combinations hold promise. Their choice and application should result from a careful balancing that seeks to do in concert what none could accomplish alone. This study has identified and conducted a preliminary analysis of a set of policy instruments with potential to increase market prices to a reasonable and sustainable level and effectively manage the excess capacity in U.S. agriculture. This set includes a combination of (1) acreage diversion through short-term acreage set-asides and longer-term acreage reserves; (2) a farmer-owned food security reserve; and (3) price supports. Acreage Set-Asides. The main objective of annual acreage set-asides is to avoid or to reduce the current tendency toward very low prices by inducing farmers to idle a portion of their working cropland. Longer-term land retirement in the form of a Conservation Reserve Program -- a tool already in use -- would serve to curb excess productive capacity. Farmers could select some of the most environmentally sensitive cropland and thus ease the environmental burden caused by farming activities. Inventory Reserves. The second policy element, a food stock or inventory management reserve program, would reduce the occurrence and modify the size of price spikes for major commodities. In exchange for a storage payment, farmers would enroll a share of their production in an on-farm storage program when prices are below a threshold level. When prices rise above the threshold, producers would be provided with an incentive to sell their reserves until the price dropped. Price Supports. The third policy element, price supports, would provide an added measure to help avoid price collapses. Government price supports would be activated through government stock purchases triggered when prices fall below a threshold level, or when set-asides “miss” a low price event. The authors used a simulation model to examine the impacts of this specific combination of policy measures on production levels and prices. The results of simulating these policy changes are remarkably clear: not only would total cropland planted to the eight major crops drop by 14 million acres in the first year, but prices for the major commodities would increase from a low (for soybeans) of about 23 percent to more than 30 percent for corn, with rice and wheat not far behind. The general increase in the prices of all commodities would lead to net farm income levels close to and above that obtained through a continuation of the status quo, while at the same time reducing government payments significantly below the status quo projections, saving about $10 to $12 billion per year. Beyond these advantages, production levels could be managed by the diversion of acreage away from traditional tradable crops and toward a non-food, non-tradable crop, such as a bioenergy-dedicated crop likes witchgrass, a perennial grass native to the U.S. with high cellulose content.(6) When the annual set-aside was replaced with an incentive to develop a bioenergy-dedicated crop in the simulation model, results demonstrated overall levels of price increase comparable to those achieved by the set-aside policy. This illustrates that annual set-asides, while convenient, would not have to be a necessary component of the program. Further, results similar to those demonstrated by introducing switchgrass could also be achieved by expanding the acreage enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). Such an approach may also contribute additional environmental benefits. Moreover, if necessary, land diverted to bioenergy- dedicated crops or placed in the CRP could be brought back into production of major crops if unexpected weather or other events jeopardizes the supply of food or demand conditions warrant. Because the U.S. is a major crop exporter and price leader, this policy blueprint would have immediate impacts, though over the short run. To sustain the improvement in farmer income over the long term, the U.S. would have to be joined by other major agricultural players. A Farmer-Oriented Agricultural Policy This illustrative policy blueprint is described as “farmer-oriented,” because fair prices from the marketplace would contribute less to concentration and consolidation of corporate control over the farm-to-consumer chain. Net farm income for the U.S. agricultural sector as a whole would be approximately the same as under the scenario of continued present policies, yet independent diversified family farmers would once again have every reason to believe they could continue in farming, preserving their rightful role in the production of our food. Family farmers would have more hope for better incomes than under the often-unfair subsidy based system. U.S. government outlays could drop by more than $10 billion per year, certainly good news for taxpayers. And most importantly, perhaps, it would discourage dumping U.S. products into vulnerable developing countries. Higher prices would be transmitted to the world market, helping to restore the prosperity for rural economies on which national economic development relies. It is time to acknowledge that the lowprice U.S. farm policies benefit agribusinesses, integrated livestock producers, and importers, but are disastrous for the market incomes of crop farmers in the U.S. and around the world. Any policy that fosters continued low prices for staple foods is a guarantee of continued crisis and worldwide distress. Since U.S. policy affects farmers well beyond our borders, the welfare and future of those farmers must be part of the vision in crafting new approaches. It is time for a new Farm Bill for the world. All major exporting countries must recognize that they too bear a heavy responsibility to cooperate with the U.S. in such an effort. U.S. policy changes alone may yield positive results in the short run, but more permanent benefits will require international policy efforts. High prices alone will not guarantee sustainable livelihoods for the world’s poorest farmers. A range of national and international policies, from credit, land, technology and transportation to tariff protection and access to markets, are essential if agricultural production is to bring a better future for farmers. It is certain that in the absence of higher prices for producers, the U.S. is export ing poverty, while jeopardizing its own diversified family farm base. Current WTO rules do not expressly prohibit the use of price support and production control policy mechanisms considered in this paper. Instead, WTO commitments place a cap on the overall level of farmer payments. These mechanisms included in the policy blueprint are not in line with mainstream trade liberalization thinking. WTO promotes policy choices that rely on the assumption that some “invisible hand” in agricultural markets will move the sector -- prices, supply, demand, income, structure, distribution, and the works -- to a higher plane if left to the devices of the free market. Ending today's crisis must become the most urgent mandate of those who write the rules governing domestic and international agriculture and trade policy. The way out lies not in more of the same but in a balanced application of policy measures left discarded in our headlong rush to an imagined “free market” in agriculture. Farmer prosperity in the U.S. and the developing world is not only possible, it is achievable. It can be ours at less cost and within a shorter time span than the hoped-for benefits of liberalized agricultural trade promised by the wealthy nations of the world to their developing country counterparts. The choice is ours to make: whose future will be protected, and what kind of global food system will be the outcome of U.S. agricultural policy? © 2003 Agricultural Policy Analysis Center. Copying is permitted for educational or noncommercial use with adequate attribution to the source. Visit the APAC website for a complete electronic version of the publication and related materials: www.agpolicy.org Published in In Motion Magazine October 5, 2003. Also read:

|

||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World || OneWorld / US || NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2011 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |