|

"He co-produced the Los Otros debut album with Cesar Rosas,

plays guitar, sings and writes some of their songs."

An Interview with Chris Gonzalez Clarke

Part 1 - Chicano GrooveInterview by Nic Paget-ClarkeSanta Clara, California |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

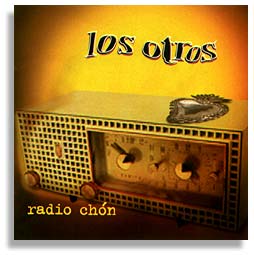

Chris Gonzalez Clarke is a member of the musical group Los Otros. He co-produced their debut album Radio Chon with Cesar Rosas, plays guitar, sings and writes some of their songs. With Gina Hernandez he co-founded the Son del Barrio recording label. This interview was conducted by Nic Paget-Clarke on January 10, 2000. Trying to make notes come out of a trumpet In Motion Magazine: When did you start making music and why? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: I played trumpet when I was in sixth grade. I don't know if that counts as making music, that was trying to read notes on a page and trying to make them come out of your trumpet. But, like a lot of people I got frustrated with it after a year and dropped it. In retrospect it was good learning a little about music and notation. My brother always played guitar and I picked that up from him. There was always a guitar in the house as long as he was there. My grandfather as well. He used to learn guitar from a Spanish-language TV show. In Motion Magazine: Where was this? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: In Antioch, California. The program would show you the basic chords. I remember watching him a lot when I was 4 or 5. But I didn't really get serious until college (editor: Stanford University), until I was eighteen. It was the dorm environment. A lot of people played. The people next door played. Somebody downstairs played drums. There was a bass player down the hall. This was right after punk rock had been a big deal. There was a feeling that anybody could play. Especially if your heroes were the Clash or the Sex Pistols who were playing three-chord songs. Anybody could do that. I learned how to do that my freshman year. We played a lot. We ended up forming a band and playing songs we liked in the dorm lounge. In Motion Magazine: What was the name of that band? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: We had a ton of different names. We were the Immigrants, the Smiths (before there was a band called the Smiths). We were Total Potato for a while. We had lots of names. We played punk rock, and rock and roll. Simple songs. We played a lot of parties on campus. We did that for a couple of years. My sophomore and junior years we were playing all kinds of parties, campus frat parties, getting paid. It was pretty neat because I didn't have to have another job. The big thing for me was going to a Clash concert and seeing Los Lobos open for them. It was the big experience that transformed what kind of music I wanted to play. Going to a punk rock concert in San Francisco, sitting there waiting to see the Clash, not really knowing who was opening for them. And these guys come out and presented themselves as an obviously Chicano group, something I had never seen before in a popular music venue. Of course, there were Chicano bands that I had been exposed to growing up, mostly wedding bands. For example, Jorge Santana, Carlos Santana's brother, played at my cousin's wedding. And I remember me, a 7 year old kid, telling one of the band members at the break that they were really good. I had been exposed to music like that growing up but was a little too young to develop a real loyality for the Latin rock movement. So, as a young adult going to see a punk rock band and seeing these guys take over the stage with the Virgen on the skin of the kick drum, playing accordions ... . They used to wear pendletons back then. It was really mind-boggling. They played a mixture of Tex-Mex and Norteño and rockabilly. It was great. It was really cool to see their mixture. The idea of them playing in front of this punk crowd. It was something brand new. Who would have thought? You'd think you'd have to play like these folks from England. To see these guys up there playing a total Chicano sound in front of this crowd was amazing. In Motion Magazine: How did the audience receive Los Lobos? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: Most of them were throwing stuff at them. Typical punk response. But they had their fans. They had people who they made their impact on. Certainly me and some folks I was there with. In Motion Magazine: So then what happened? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: This was about the time that I became active politically in MEChA and other Chicano movement issues so, there were always community events that required music. I and a small group of friends, Charlie Montoya, Chris Flores, Lucky Gutierrez and other folks would play campus events at the Casa Zapata, at MEChA conferences, at rallies or whatever. We spent our time learning Chicano folk music. Stuff like Los Peludos, Enrique Ramirez's first recording. The first Los Lobos album, Just Another Band from East LA which was all-acoustic. Chicano music like Jose Montoya's album Casindio. When someone like Montoya or Enrique Ramirez came to campus, we might open with a few songs. Once, Enrique brought us onstage to accompany him on Aqui no Será, because he probably knew that we had learned every song on that album. Ozomatli released a version of that song on their CD, which is cool, because it's fairly obscure. It's a tune that only Chicanos or activists would have ever heard. Dr. Loco's Rockin' Jalapeño Band In '88 or '89 our group opened for Dr. Loco, Jose Cuellar. After the show Jose asked me and Charlie if we wanted to play with them because he was starting a new band. That band became the Rockin' Jalapeño Band. I spent a long time playing with those guys. In Motion Magazine: How long was that? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: About nine years. In Motion Magazine: How would you describe that music? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: Primarily Tex-Mex-based Chicano music. Really it was like a modern day Tex-Mex orquesta. We were influenced by groups like Little Joe y La Familia, Esteban Jordan, Sunny Ozuna and the Sunlighters. Many of our early tunes were rearrangements or reworkings of songs they had recorded in the '70s like Cumbia del Sol, Vuela la Paloma, etc. We did a lot of songs that were influenced by orquesta in terms of the use of horns, a bigger band with keys, bass, guitar, percussion and drums, throwing in different chord progressions versus straight-forward 1-4-5 chords. We added a little bit of California-style Latin rock like Santana. It was a Chicano group. A variety. In Motion Magazine: Was there a context for the music? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: There was definitely a political context, a connection to the political issues of the day. Some of the first crowds we played to were the college MEChA crowd. Activist-oriented crowds. Certainly a connection to the UFW. That's where we got our start, playing benefits for universities, MEChA conferences, that kind of thing. In Motion Magazine: This was up and down California? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: Primarily California. We would go to Texas and to Colorado as well. In Motion Magazine: How were you received? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: We had really great reception. I think that one of the best audiences that we always connected with was in East L.A. at the Plaza de la Raza, a community center in East L.A. We would play there once or twice a year. It was always packed and people really really liked it. It was a cool band because it was inter-generational and we could play songs that people who were my mom's age were familiar with and younger audiences would also dig. Songs from the '50s, or '60s or '70s. We would update them for younger audiences. There was a broad appeal across generations. We could play to a group of college kids or folks who were much older than that - three times that age. The music didn't belong to just one segment of the people, rather a broad range of people could identify with it. In Motion Magazine: This was done consciously? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: Yes. A lot of the songs were from Jose's time, songs like Framed or Honky Tonk. R&B and Tex-Mex songs. We spent a lot of time customizing them, arranging them for a contemporary feel. That was definitely part of his vision for the group, to appeal to a whole spectrum of people. In Motion Magazine: What does it mean to realize that you want to do music for ever? Is that a safe assumption with you? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: Yes, it's a safe assumption. Something we used to always say in the Loco band was, 'we don't do it because we want to, we do it because we have to.' Once we got bit by the bug it was something that we had to do. It had to be part of our life. To this day if I'm home at night a couple of weekends in a row I feel like something is wrong, I'm missing something. I'm up late no matter what on Thursday, Friday, Saturday nights. It's just automatic. It's something you have to constantly negotiate for people who are doing it part-time, balancing jobs. You spend a lot of time with other musicians, rehearsing, or whatever, while other folks are watching TV or hanging out with their significant others. It takes a lot of understanding from your partner - definitely. In Motion Magazine: What do you say to people who think that this is what they want to do? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: To me there's nothing I would rather do. It's what I love. One way or another I would be doing this. I'd spend time on it whether anybody was listening or not. Whether people come to shows or not. It's something that I would still be doing. I'd still be writing, I'd still be playing at home. You have to know that you can't be concerned about being a huge success or being a household name. That can't be your goal. Your goal has to be the music and you have to love that. There's a lot of time when you are just practicing your instrument alone. That's what it means. If you don't get something out of that you are not going to do it. I'd say you need to know that you love it. In Motion Magazine: At what point did you decide to, or did you always, compose music? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: It was something that I always tried to do. Even when I barely knew just a few chords I was always working on ideas. Usually the ideas were themes in terms of lyrical content. Trying to work out ideas, put down ideas I had on to paper and then fit music to them. I think, now, after playing for a while my approach is a little more musical. That's changed over the years, but the desire to create has always been there. In Motion Magazine: Do you experiment with the music or are you refining traditional techniques. In order to express something that you haven't seen expressed any other way do you try to figure out another way to express it? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: I definitely do that. Sometimes you have an idea for a lyric or for a concept of a song like "what would it sound like to combine the way Al Green did his rhythm section in Let's Stay Together with the idea of a Cuban ensemble." Sometimes I work that way--to combine influences in my head in a conscious way -- then I try to do it. Or I may have an idea for a song and think "how would the Band"- Robbie Robertson and the Band is a big influence for me - "how would Robbie Robertson tackle this song? How would he have written this song?" I adopt some characteristics of a voice in an attempt to find my own. It's pretty hard to say you'll just create something out of the blue. Everybody's influenced by everything that is out there. For me I might listen a lot to certain records to set me down a certain path.

In Motion Magazine: Where did you get the name Los Otros? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: We had a poll at one of our gigs. We had names on the ballot like Cucarachas Enojadas (The Angry Cockroaches), Manteca y sus Chicharrones (Lard and the Pork Rinds) . A bunch of crazy names. At the bottom of the list we had "other", and somebody checked it. maybe a couple of people checked it. Los Others. We liked that one the best. It's memorable, you won't forget that one like "Los Happening Jarochos". That was our first totally forgettable name. In Motion Magazine: How did Los Otros get started? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: We started out doing folk music, jarocho music, in particular, from Veracruz. We did that for quite a while. We played in Ed Robledo's living room. Then there would be a backyard party and we'd say "let's play for it." After a year and a half we decided to try and get some gigs. In Motion Magazine: When was this? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: That was in '97. Next, we decided to spend a week together writing. We were all writing. We knew that for whatever reason what we were writing didn't fit the other bands that we were in. We got a friend and relative of Ed's to manage us, Pancho Rodriguez and he and another friend from the Teatro Campesino, Phil Esparza, set us up to go to CSU Monterey and we spent five days in a big room, actually a sound stage. We brought down some recording equipment that we borrowed from another friend, Tony Cazares, and we recorded our demo. We finished four or five songs and we started writing three others. The process was great. We realized that there were a lot of ideas in the group. The group was wide open. We were starting from scratch, creating our sound and our repertoire from scratch. In our other musical situations we were fulfilling to some extent other people's expectations of us. In this new situation we were writing for ourselves and satisfying our own curiosity about music. I've recorded in a lot of different situations and it's difficult to achieve freedom when you are working with a lot of folks with their own musical opinions. There's a balance between being too critical of other folk's style and giving people the opportunity to say what they have to say. With this group we didn't have a lot of huge egos involved. We were free to step back. It was a unique grouping of individuals who were willing to put aside their own personal ego for the music. People who could look at a song and say "What does this mean, can you clarify it? Or I can't really sing this. You should sing this. You have a better voice for this." Or, "You should play this guitar part. I think you have a better idea for it - do it." In short, the group would do what was right for the song. In a band, if you can start off with that type of operating principle it's pretty incredible. We spent the five days together. We came up with the demo and from there we started planning when it was we would cut out from the other bands we were in to start playing together as a group full time. To give this band our first priority. Our first goal was to refine the work that we had done into a CD. That's where Radio Chon came out of. In Motion Magazine: What is Radio Chon about? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: The concept behind the album is that Radio Chon is a pirate radio station, an underground radio station. The CD starts off with a question. "If Marlon Brando gave you a million bucks what would you do?" The song's response is that we would build this underground radio station, pirate radio station. And Chon is the fictional uncle, one of our uncles whose garage we would have this radio station in and where we would play all the music that you hear on the CD, and also music by Quetzal, Ozomotli, all the Chicano Groove bands. It's actually a real live thing that happens. People do this 'micro broadcasting.' In Motion Magazine: They do? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: In East L.A., they had a station which played these Chicano bands, spread consciousness, talked at Zapatismo. . . They even had a system to take requests from the listeners. But it was totally undeground, unlicensed. Quetzal was going to do a fundraiser for the station, and they got a call from the sheriff that the FCC had received some complaints against them and they were going to shut down the fundraiser if it happened at Griffith Park or wherever. Furthermore they were going to arrest these people. Shut down this pirate radio station. I thought the idea was so funny. I pictured someone driving home listening to one of the major stations and all of a sudden this pirate station takes over your radio for however many blocks. They couldn't have broadcast for more than a couple of miles. But it was obviously of great concern to the sheriffs and the FCC. We talk about it somewhat fictionally and also take a little bit from real life. In Motion Magazine: What is the song So far from God about? Chris Gonzalez Clarke: My grandparents. It's trying to think about what their experience must have been coming here in the '20s as very, very young people. Leaving their country and never going back. I wondered. They came from Penjamo, Guanajuato, Mexico. We'd always hear the stories of them coming over here. My grandfather dealing with his first winter in Chicago. Working in steel mills, dealing with snow for the first time. The cold. Being lonely. Going back and getting married and coming back over here. Starting our family here. The song is about that. Wondering if he understood that this decision that he made to come here when he was 18 or 19 or 20 would have such incredible ramifications. That he would be here forever. That something that he maybe did on a whim as a young man turns out to be a moment that defines his entire life and those of all the thirty grandkids that he has here. Click here for Part 2 - Son del Barrio Published in In Motion Magazine May 9, 2000 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2020 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||