|

The Significance of the San Andres Agreements

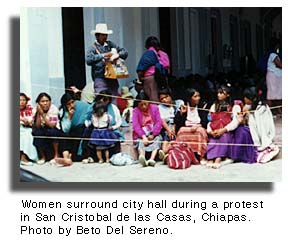

for Civil Society (A reading of the agreements from the Concrete Jungle) by Javier Elorriaga Translated by Cecilia Rodriguez San Cristobal de Las Casas Chiapas, Mexico

It is important then to understand the particular form of dialogue and negotiation which allowed the agreements about Indigenous Rights and Culture to develop, and which allowed there to be progress in terms of its implementation. We should make it clear that the significance of the recognition of collective rights and the broadening of citizen's rights, can be claimed as valid and legitimate rights for other sectors of society; mestizo farms and residents of the city. In San Andres a new form of dialogue is constructed; with the government and with civil society. With the government the negotiation is open and in full view of society. Only those proposals which contained an ample consensus among groups, organizations and personalities who participated in the dialogue were presented in the negotiations: the Zapatistas and civil society created that space for discussion and constructed that consensus together. San Andres inaugurated new methods, truly democratic, of promoting the constitutional changes which Mexico needs. The government refuses to accept the concept of "popular initiative", which should create the mechanisms by which citizens can initiate and propose laws to the National Congress and local legislatures. Nevertheless, through its actions, the indigenous movement has managed to raise national consciousness around the need for constitutional reforms; it has given body to its proposals until they evolved into formations with applicability to the Constitution; and together with the EZLN, it forced the government and the legislators through the Commission for Concordance and Pacification (Cocopa), the commitment to promote a consensus constitutional reform. Zapatista logic opened a path in order to progress in the reform of the State. Instead of secret and high-level negotiations, or forums controlled by government institutions, consensus are being woven from many diverse local spaces, and with the participation of all the sectors affected by these problems. In an era when only regressive reforms make progress, under a neoliberal model which continually restricts or cancels social rights, the agreements of San Andres amplify and secure the recognition of collective rights; for indigenous people, of course, but these can easily be extended for the rest of the population. Following the Zapatista slogan of "command by obeying" and the indigenous traditions which see authority as a mandate of service to a community and not for personal advancement, the agreements of San Andres can ground the basis of a new relationship between those who govern and those who are governed. The Zapatista proposal is to amplify citizens rights and create new spaces of participation. The installation of the Commission of Verification and Continuity, composed of representatives of the EZLN, the federal and state government, and by organizations and personalities of civil society of high social standing and moral quality, create a fundamental space which guarantees the application of the agreements signed in San Andres; it secures the participation and the vigilance of society and can become a space of citizen decision-making of national significance. In the Dialogue of San Andres, the encounter between the Zapatistas and civil society created the conditions which serve to fortify a national indigenous movement; it created new regional organizations, gathered many others and broadened the horizon of struggle. The pace of negotiation with the government became a space of civil expression and permitted the construction of consensus and organization: social mobilization. Towards a new relationship between those who govern and those who are governed The reforms won by the indigenous people are new footpaths which can be used by other sectors of the population in order to win new rights. In San Andres it was agreed to establish a new relationship between the State and indigenous peoples, in which the federal government commits itself to regulate its actions in accordance with the following principles:

Following these general principles, which should be extended to the totality of municipalities and communities in the countryside and in the cities, the agreements of San Andres introduce the possibility of the construction of a new relationship between those who govern and those who are governed. In the agreements the rights of indigenous peoples to participate in all the instances of government, establishing the obligation of the State to guarantee and respect these spaces. These conquests are expressed in three arenas:

|

| Part 2 -- New relationships in the community, in the municipalities, in public policy 1. In the Community

In the reforms it is established that authorities are obligated to carry out the transference of functions and resources to the communities, so that they themselves can administer the public resources which correspond to them. Additionally, these communities should be incorporated into the town halls, by naming their own representatives. The principle of self-development present the ability of the communities themselves to determine their projects and programs. That is why it is necessary to incorporate in local and federal legislatures the mechanisms for citizen participation at all levels, so that the projects of development can be designed taking into account the aspirations, necessities and priorities of the populations involved. The communities have the right to designate freely their representatives, within their community as well as in the organizations of municipal government, in compliance with the institutions and traditions of each people. The right of communities and municipalities to incorporate with others in order to unify efforts and coordinate actions, optimize resources, promote regional development projects and the defense of their interests is also established. If these rights which have been won by indigenous people are made valid in rural communities and in urban neighborhoods, it would be the citizens who would exert their right to organize and to elaborate their own development projects, without subjecting themselves to government programs decided from above and oriented to fulfilling the whims of successive administrations. 2. In the Municipalities In the agreements it is said that a "re-organization" of municipalities must occur, in order to adjust territorial borders to social and cultural processes which have been developed in them. It is established that this process should follow the results of the consultation of the populations to be involved. Indigenous municipalities won the recognition of their own internal and democratic forms of government, such as decisions made in assemblies, town hall meetings, and plebiscites. These methods are especially important for small farmer municipalities, where it is necessary to develop a form of direct democracy. It was agreed as well that municipal agents and officials ( such as aldermen, or commissioners, etc.) would be elected by citizens, and not appointed by municipal presidents. Citizens would have the right to remove their representatives, in case they do not comply or disobey the trust of the people. The agreements of San Andres established the right of citizens to take away authority from municipal authorities, and the right of local Congresses to seek the mechanisms by which their decision is respected. It is also established that citizens have the right to initiate laws or decrees, through proposals made to local Congresses, through their municipal authorities or through popular initiatives. There is not reason why these rights cannot be claimed all over the country, or why they should be applied exclusively to indigenous people. They should be extended to all. It is very important to point out that it was agreed to develop legislation about the rights of communities to elect their own authorities without the necessary participation of political parties. In this point the possibility for independent candidates is opened for benefit of all. The constitutional reform which proposes that town halls should allow populations to participate in all the plans of municipal development and above all to establish mechanisms of citizen participation to collaborate with town halls in the programming, exercise, evaluation and control of resources, including federal ones destined for social development is very important. It is agreed as well to develop a process of de-centralization of the facilities, functions and federal and state resources to municipal governments. Municipalities are given the right to incorporate freely among themselves in order to coordinate and initiate regional actions which will optimize their efforts and resources, increasing in this way their capacity for development and gestation. The authorities are obliged to transfer their resources, so that municipalities themselves may administer public funds which correspond to them. This can be very significant for urban as well as rural municipalities, because it makes possible the development of programs and the management of sustainable resources in a scale larger than the municipality. 3. In public policy The new relationship between indigenous peoples and the State should be based on the principle of consultation and agreement, and in democratic de-centralization. Therefore, the policies, laws, programs and public actions should be consulted with the communities. The state should commit itself to sustain the principle of integrity and to promote the concurrence of all the institutions and levels of government, avoiding partial practices which fracture public policy. In order to make sure that its action corresponds with the characteristics of diverse communities, and to avoid the imposition of policies and homogenizing programs, the state should guarantee citizen participation in all the phases of public action, including its conception, planning and evaluation. The State commits itself as well to carry out a transference of facilities, functions and resources to municipalities and communities, in order than public funds be distributed appropriately. Since public policy should not only be conceived by the communities, but implemented with them as well, the actual institutions of social development should be transformed into others which operate in conjunction with these communities. The commitment for the different levels of government and institutions of the State not to interfere unilaterally in the affairs and decisions of the communities, in their organizations and forms of representation and in their current strategies for use of their resources. |

| Part 3 - Towards the Strengthening of Collective Rights

The focal point of the agreements of San Andres is the recognition and fortification of the collective rights of the indigenous communities and villages. They refer as well to the rights of specific sectors of the population, which can be extended throughout the country. They deal with particular rights of farmers, migrants, women and educational rights. 1. Farmers In San Andres it was agreed to "legislate so that the integrity of the lands of indigenous groups are protected"; and in the constitutional reforms the recognition of collective rights to lands and territories was established. This is relevant, because it contradicts the privatizing tendencies of ejidal and communal lands which have been imposed in Mexico after the reforms of Article 27 of the Constitution. Unresolved for indigenous people as well as for farmers is the original spirit of Article 27, a demand which was insisted upon but not won. In agrarian issues, the most significant gains were that mestizo farmers can secure the commitment of the State for sustainable development. It was agreed to promote the recognition of the rights of towns and communities to receive compensation, when the exploitation of natural resources is such that it destroys habitats of communities. In cases where damage has already occurred, the establishment of mechanisms of grievance will be undertaken so that the case may be analyzed. In both cases, the mechanisms for compensation will seek to secure the sustainable development of the peoples and the communities. It is established as well that communities will have priority in being granted the benefits of exploration and use of natural resources. 2. Migrant Workers The State should promote specific social policies to protect migrants, in national territory as well as beyond the borders, with institutional actions of support for the labor and education of women, health and education of children and young people. In rural regions, these policies should be coordinated in zones which attract and need agricultural workers. 3. Women Indigenous women at San Andres won the recognition of their right to participate under equal conditions with men in all matters which concern government and the development of indigenous communities. They will have a priority participation in economic, educational and health projects which specifically impact them. 4. Education It was agreed that the State should assure an education which respects and makes use of the wisdom of the peoples; and which guarantees their participation in the organization and formulation of regional programs. Cultural diversity should be incorporated into the plans and programs of study of regional programs. Together with indigenous people: national priorities will be reorganized. It is necessary to establish a new relationship between the State and indigenous peoples. This relationship, in addition to being based in respect for their self-determination, should depart from the recognition and compliance of a governmental commitment to re-orient public policies in order to transform the conditions of poverty and marginalization which affect indigenous peoples. In San Andres it was recognized that a new politics of the State is necessary, one which is not determined by electoral terms. The government committed itself to develop it within the framework of a profound reform of the State which should initiate actions to elevate the levels of well-being, development and justice. There are commitments which specify the obligation of the State to secure education and training in such a way that indigenous wisdom is respected and utilized. The access of indigenous wisdom to science and technology is to be promoted and a professional education which improves the possibilities of development for the communities is to be provided. Training and technical assistance which improves the productive processes are guaranteed. Training for the organizations which elevate the productive capacity of communities is to be provided. The responsibility of the State to secure the fulfillment of basic necessities by guaranteeing the conditions which will allow indigenous peoples to enjoy adequate nutrition, health and housing. In this social policy it is agreed to promote programs destined to benefit children and women. Finally, it was agreed that the State should promote the economic base of indigenous communities with specific strategies of development agreed to by them, which contribute to the generation of jobs and improve the provision of services. In terms of social policy, indigenous people managed to impose on the State a series of commitments which run counter to neoliberal policy. If they are carried out, they presuppose a reorientation of public policy and a re-definition of national priorities. And this is a task which involves not only indigenous people but all of society. |

| Jorge Javier Elorriaga Berdegue was born on May 13, 1961. Initially a student at Colegio Madrid, Elorriaga completed his education in the College of History, Department of Philosophy and Letters, at the Universidad Nacional Autonoma in Mexico. He received "honorable mention" for his thesis on geopolitics and the conflict in Central America, with a focus on Nicaragua.

Between 1984 and 1988, Elorriaga worked among the communities of Chiapas, initially as an educator in literacy and later as a professor of history. During this time he met his compañera, Elisa Benavides. They worked together in graphic design, as editors of alternative publications in Mexico City, and, beginning in 1993, as journalists for Argo Servicios Informativos in Mexico. Both were imprisoned in February of 1995, accused by the Mexican government of being members of the EZLN (Zapatista National Liberation Army) leadership. Elisa was released from prison on July 14, 1995, after having been cleared of the charge of terrorism, and in November of that same year all charges were dropped against her. Javier was released on June 6, 1996, when the Mexican judicial system absolved him of all charges of terrorism and rebellion. While imprisoned, Elorriaga wrote "Ecos de Cerrohueco" (Echos of Cerrohueco), a forceful and convincing account of the irregularities committed against him by the Mexican judicial system. Beyond an in-depth, first hand description of the Almoloya de Juarez high-security prison in the state of Mexico, Elorriaga, in words that flow from the conscience, gathers up and presents to the reader the collective "echos" of prisoners of Cerrohueco Prison (Chiapas) and the testimonies of other presumed Zapatistas captured in Mexico City, Cacalomacan (state of Mexico), and Yanga (state of Veracruz). Readers concerned with the future of Chiapas and Mexico will follow these writings into the labyrinths of prison, taste the unintentional humor of Mexican "justice," and share the vicissitudes of a historian embedded in the Chiapan conflict. Since his release, Elorriaga has devoted himself to the cause of the Zapatistas and alleged Zapatistas who remain imprisoned, and to all political prisoners in Mexico, as an issue of human rights. In August of 1996 he presented statements on Detention and Indigenous Rights at the United Nations Subcommision on Human Rights in Geneva, Switzerland. |

| Published in In Motion Magazine March 8, 1997. |

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2020 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

The San Andres Dialogue has represented profound transformations in the way in which politics is conducted in Mexico, both because of its results as well as its form. With its armed uprising of January 1 of 1994 as well as its decision to listen to large social sectors, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation has opened a space for encounter and a path of mobilization and participation for civil society.

The San Andres Dialogue has represented profound transformations in the way in which politics is conducted in Mexico, both because of its results as well as its form. With its armed uprising of January 1 of 1994 as well as its decision to listen to large social sectors, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation has opened a space for encounter and a path of mobilization and participation for civil society. In the reforms to the Constitution the community is given the character of an entity with legal standing. This means the recognition of the legal character of communities not only in the agrarian arena, as it has been until now, but in many other arenas. This gain is significant for all municipalities, rural and urban, because only municipal agencies at this time have official and minimal recognition; urban neighborhoods, un-incorporated villages and rural centers do not have any type of representation in town halls. In daily life, the neighborhoods and villages are the immediate arenas where citizens organize themselves and act to resolve their problems; the reconstitution of the communities could convert themselves into a primary space for reactivating collective life.

In the reforms to the Constitution the community is given the character of an entity with legal standing. This means the recognition of the legal character of communities not only in the agrarian arena, as it has been until now, but in many other arenas. This gain is significant for all municipalities, rural and urban, because only municipal agencies at this time have official and minimal recognition; urban neighborhoods, un-incorporated villages and rural centers do not have any type of representation in town halls. In daily life, the neighborhoods and villages are the immediate arenas where citizens organize themselves and act to resolve their problems; the reconstitution of the communities could convert themselves into a primary space for reactivating collective life.