|

TPP v. ASEAN:

The Pivot And The Island Rows "... competing to lead the regional trade liberalization agenda." by Arnie Saiki Los Angeles, California

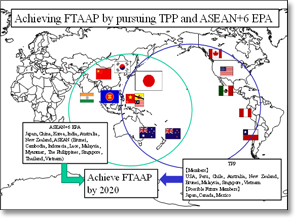

Links to footnotes open in a second browser for easy reference. When Obama heads to Cambodia to attend the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) summit, [i] he will be arriving with the full weight of his Pacific Pivot behind him. He will be asserting policy that will ensure US strategic and economic relevance in the Asia-Pacific region. Obama, however will not be alone. Since the 2004 APEC meeting in Santiago, when Chilean President Ricardo Lagos, endorsed the creation of a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP), [ii] both the U.S. and China -- the world’s largest economies -- have been competing to lead the regional trade liberalization agenda. In an attempt to meet the 1994 declaration of the APEC Bogor Goals, [iii] many have come to see the current implementation of an FTAAP in pursuing a trade and investment framework as concluding the failure of the decade-long WTO Doha Rounds. [iv] While the Doha Rounds were seen as important to sustaining the economic growth of the dominant economic powers, it also become increasingly irrelevant to emerging markets whose economies were quickly outpacing the U.S. and E.U. As the current economic agenda for both the U.S. and China will be to win over emerging markets and small economies, this article seeks to highlight the investment and trade agenda embedded in the Pacific Pivot and to prioritize the ecological and health priorities of smaller economies in the Pacific region. We are nearly a year into Obama’s announcement of a Pacific Pivot, a policy shift whereby the administration has moved 60% of military resources into the Pacific region.[v] Much of the discussion in the U.S. analyzing this pivot aims to focus on potential future conflict with China, while from the Chinese perspective, this viewpoint is seen as misguided. Luo Yuan, a retired major general and Executive Vice President of the China Strategic Culture Promotion Association asks, “Chinese people are very confused about U.S. activities. On what basis has the U.S. returned to Asia Pacific? Does the security situation of the region pose a threat to the United States? And are there any Asia-Pacific countries making the U.S. feel the necessity of sending more troops to the region?” [vi] At the Shangri-La Security dialogue this year, Defense Secretary Leon Panetta rejected the view that increased emphasis by the U.S. on the Asia-Pacific region was some kind of challenge to China. [vii] However, as Secretary of State Hillary Clinton just announced last week in Australia, “From the Indian Ocean to the Pacific Islands, American and Australian navies protect the sea lanes through which much of the world’s trade passes ... our growing trade across the region, including our work together to finalize the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), binds our countries together, increases stability, and promotes security.” In reference to approving the new U.S.-Australian Defense Trade Cooperation Treaty, Clinton adds, “This agreement will boost trade, help our companies collaborate more closely, and spur innovation. It’s a definite win-win.” [viii] As we begin to consider the heightened line of new and/or renewed disputes with China over islands and sea-lanes between Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Malaysia, Brunei–and now Japan over the recent conflict over Senkaku/Daiogyu island, [ix] it would appear that the U.S. is focusing its military security on these disputed regions and sea-lanes, of which China’s shipping depends. [x] Currently, the U.S. has no international legal standing to assert a policing presence in these disputed territories, so they are working on a series of bilateral cooperation agreements throughout the region, which includes the U.S./South Korea agreement to build a military port on a UNESCO World Heritage site and Biosphere Reserve on Jeju island. [xi] Complicating matters further, the U.S. is also expected to ratify the U.N. Convention of the Law of the Sea, which will provide the U.S. with the legal framework to take on regional military action in these disputed waters.[xii] At the November 2011 East Asia Summit on the issue of the South China Sea, the US declared that much of which China claims, is under the jurisdiction of international maritime law and any disputes over the area must be resolved through multi-national cooperation and dialogue. China, in contrast, declared that any disputes over possession of the South China Sea should be resolved bilaterally, rather than multinational forums or talks. [xiii] At the current meeting in Cambodia, leaders agreed not to internationalize the maritime disputes, which sets back any attempt to heighten the South China Sea rows, [xiv] and they would continue to draft a legally binding Code of Conduct document. [xv] Prime Minister Noda’s long held attempt to move Japan closer to joining the TPP, inflated the conflict with China and should not be underestimated. In addition to the Senkaku/Daiogyu dispute, Japan and South Korea have also resumed tensions over the disputed Dokdo/Takeshima Islands, further postponing the possibility of concluding an ASEAN+3 (which includes China, Japan and South Korea). The geopolitical manufacturing of this island row should be considered as sabotaging this year’s ASEAN round, [xvi] and while the TPP has been unpopular with the Japanese people, it is possible that any heightened military escalation in the region over these islands could generate public support for both the U.S. military expansion and the TPP. Upon closer examination, these territorial disputes with China have been taking place among a region that -- using a Vietnamese proverb -- understands that “the sun is good for cucumbers and the rain is good for rice.” Countries participating in the TPP (or as with the Philippines and Taiwan who are negotiating bilateral Trade and Investment Framework Agreements (TIFAs) with the U.S.) are also the same countries committed to the ASEAN regional alignment that could also derail the TPP. In order for the U.S. to insert itself in the region, it needs allies that will wedge the ASEAN+ door open long enough for the U.S to embed those US-led North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)-style, trade and investment rules that can enforcibly bind the U.S. to the region. [xvii] What this means for the U.S. is that should ASEAN +3 conclude, the U.S. is less likely to lead the rules for investment and trade. A Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) among the ASEAN countries and its economic partners will immediately amount to an economic cooperation whose combined GDP (nominal) will be around US$16.2 trillion dollars. If ASEAN +6 (Australia, New Zealand, India) concludes that will amount to roughly a $19.7tn partnership. For reference, the GDP for the EU is around $17.6tn and the US is around $15tn. If the TPP, in its anticipated 13-country alignment (which may soon include Japan and Thailand), is concluded that will amount to a $26.7tn alignment. [xviii] For both China and the U.S, leading regional investment and trade does not mean that it will exclude each others economies, as it is likely to become even more integrated and globalized in the future. The competition will determine who will gain the most influence in determining the rules of investment and trade in the region, and who will have the greatest access to resources in developing resource-rich regions like the Pacific [xix] or Africa, [xx] where China is currently dominating. An ASEAN alignment will also likely embrace BRICS, while the TPP will continue with the dollar’s continued hegemony as the international trade currency. By conducting transactions independent of the dollar as the trade currency, it will reduce transaction costs and lower the risks involved in settlements at financial institutions. Developing countries seem to prefer the BRICS state-owned investment process rather than the structured loans of financial institutions that can often lead to institutionalizing punishing deregulations. Despite the proliferation of an alphabet soup of regional economic integrations, both ASEAN +3/6 and the Trans-Pacific Partnership have been the dominant regional agreements working to conclude this year or next. This geo-political football being played out for Asian and Pacific markets and resources are being competed for primarily between the US and China, and this competition impacts not only rules for investment and trade, but also human rights, militarization, access to sea-lanes, resource extraction, fisheries, migrant labor, currency and financial rules, among others. Pacific Plan Whether ASEAN’s $16.2/19.7tn or the TPP’s $26.7tn alignment, both formations lead to the creation of a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) that threaten the ecological bio-diversity and resource-rich Pacific Island nations whose economies are so small (on average, about $450 million) that individually, they will be unable to withstand the economic pressure coming from the investment regime. The ecological consequence of an expanded and hyper-globalized supply chain of this magnitude will be disastrous in an area -- the third of the world’s surface -- that is already confronting challenges to rising waters resulting from climate change, radiation poisoning, depletion of fisheries and reefs, and extreme degradation resulting from industrial extractive technologies. The human and ecological costs have already impacted Pacific Island Countries (PICs) and heightened economic hegemony will likely be disastrous. In 2010, the US announced closer cooperation with the Pacific Plan, [xxiii] an agenda drafted in 2005 by the Pacific Island Forum (PIF), a 16 member-state inter-governmental agency representing Pacific Island countries (PICs). The Pacific Plan is described as “the master strategy for regional integration and coordination” in the Pacific. [xxiv] One of the dominant threads of the Pacific Plan aims for political and economic integration among PICs and the creation for more investments in the Pacific in line with liberalizing regulations and trade. The Pacific Plan has been criticized by Pacific Island activists for not representing the needs of its people and for being too influenced by the larger neo-liberal economic agenda of Australia and New Zealand. In line with this agenda, one of the objectives for the U.S. has been to support public-private partnerships with not only businesses but also sub-regional institutions and other civil society organizations that the U.S. has identified as being good partners. Starting before the APEC meeting in Hawaii in 2011, there has been a steady build-up of military systems in the Pacific and this includes the kind of infrastructure and security services in the region that essentially paves a super highway for Wall St. to drive new regional investment. |

||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2018 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |