|

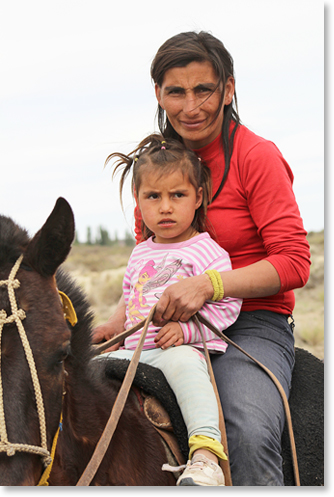

Interview with Yanet Alarcón, Chos Malal, Neuquén Province, Argentina

This interview was conducted (and later translated and edited) by Nic Paget-Clarke for In Motion Magazine on October 16, 2014 in Chos Malal. Chos Malal is a small city (formerly the capital of Neuquén Territory) in the north of Neuquén province, Argentina. Chos Malal is located on the banks of the Neuquén River as it flows out of the Cordillera del Viento (Mountain Range of the Wind) near the Andes Mountains and the border with Chile. Leer la entrevista en español: clic aquí.

Transhumance livestock herders Yanet Alarcón: I am Yanet Alarcón. I am with La Mesa Campesina del Norte Neuquino. I am a member of a family of transhumance herders who migrate each winter and summer. I don't live in the countryside but I help with the family work in whatever way I can. (Editor: transhumance herders move/migrate with their livestock in summer and winter between fixed pastures. Each season they travel a hundred kilometers.) My parents brought me up raising production animals, mostly goats, some cattle, and horses. They would do the work of driving the animals, which means moving the animals from the winter pasture to the summer pasture in order to make good use of the fields for the animals, so that the animals could fatten-up and do well in the winter. This is a historic form of production in this area (zone). We continue doing it and I’m sure we are going to continue doing it for many more years. We have had many conflicts and continue to have many land conflicts, because the herding trails were being closed -- historic paths, without fences, along which the animals used to travel for five, fifteen, twenty, thirty days, from the winter to summer pasture and vice versa. Those trails were being closed. And those lands were being sold to other people in the area that we didn’t even know. And now the trails were being closed off with wire fencing, leading us to herd along the highways. On the one hand, there are conflicts with motorists using the highway, and on the other, lack of food has caused death or extreme suffering for many of the animals. Already we are left with a reduced pathway bordered by fences. Because of this, we have joined together in an organization that comprises the majority of social organizations and Mapuche communities in the area. It is called OUDA: “United Organizations in Defense of Herding,” and what it seeks to do is to defend the historic herding trails, to recover them. Also, we are for improving our life in the countryside, the life of those who continue in the countryside, the life of those who are in the city and continue also making our livelihood in the countryside. As a way of organizing ourselves, we adopted horizontality where we all have our participation and a voice so that we are able to make decisions. That was, and continues to be, very important because it has helped us and takes into account what we think, our way of life, our form of production, and our economy which is a regional economy that is sustaining but also contributes to the productive growth of our zone. Well, on this road that we are on, we are defending our way of life in the countryside and defending the herding trails and the life of the herding families, who have been herders, and who will continue to be herders for many more years. Mauricio Parada: Well, I am Mauricio Parada. I am a herder. A little of my history -- like that of many livestock-herding families, a particular issue arises which has to do with a father teaching one of his sons, for example, so that he will work in the countryside with him. We are six brothers. Of those six brothers, one was he who worked and lived in the country, and I was one of those who wanted to study. You see, I wanted to emigrate to study, to finish high school, to finish everything -- including going to university. And afterwards, by my own choice, I have returned to the countryside and dedicated myself to working in the countryside. It is a reality for the man who works in the fields that since he works with his body with his, let's say his physical strength, the years take their toll and many people end up abandoning the countryside (they end up having good animals). And, because they are old, they emigrate to the city -- intending to buy a house so that they can live in a place closer to where they can be taken care of, and so forth. If it rains or it doesn’t rain In my case, well, I returned to the countryside where I was working with my parents who are almost 80 years old and, well, I try to live in the countryside, which is very difficult. It is a beautiful life but it is a life that with respect to the financial issues sometimes it has its pros and cons like any other job you have where you are self-employed, because you have to manage and support yourself. Here, nature greatly affects the good years and the bad years: if it rains or it doesn’t rain; if the fields have pastures or if they don’t have pastures. And so, taking off from there, one sets about planning how to produce, your production goals, let’s just say that this is common to all, because we all do the migrating. We all have the winter and summer pastures but it can also vary according to how things are going for us, let’s say in productive terms. In our case with my family, our tendency is more towards cattle, we breed more cattle than goats. We also have goats and horses. But, well, the issue of raising cattle is more complicated in this zone because there are no fields for cattle grazing (editor: there are no fences). It’s a specific issue. (But) In terms of the country life, for example when living in the city, and in my case, many times you end up very closely involved, or you feel that you get in too deeply into consumerism. When one goes to the country and you’re there for a month, fifteen days, twenty days and you come back to the land, one feels this. That which used to be done, which in reality was the good way, was, for example: building for oneself in accordance with nature, using firewood; being able to prepare your food over a fire: being able to drink water, when now around here a person says, "I’ll just drink a soft drink." Right? That’s how I feel in my specific case when I spend a season out in the country. I feel that the land once again envelops me, and it teaches me that much of what we do is superfluous. In reality, life is nature -- just like the life that the first people had -- and this way we are continuing to maintain it. Where are we going generationally? My particular concern is that the countryside teaches me about solidarity; that being in the countryside makes us depend on each other. Perhaps someone isn’t so close, but we know that he is there -- for example, the neighbor who is two or three hours away by horse. We always need someone to be able to relate to. And we suffer a lot from a feeling of being uprooted: of leaving family here; of going away to the country for a long time; of being alone a lot, or with someone else, but generally with oneself. In my case, I often spend a lot of time alone. When one has to face that life question, of having to say, "I must leave and sacrifice myself" and leave many things, my family, which isn’t a country family, that does not live out in the country -- for me to be able to make such a life, let’s say, it becomes a conflict for me. What do I do? My daughters, do I bring them to the countryside so they can live in the country or do I leave them to become urbanized and follow another way of life that is going to be much different from that which I lead? You know what I mean? And thinking how far will one go? Mmm? To think, where is this going to lead? Mm? Where are we going generationally with the country life? Who is going to follow along? A summer pasture that we have occupied for more than a hundred years -- who is going to continue occupying it? I have two grown daughters. These are all matters that have to do with daily living, and with confronting a reality. Also, in my case, I intend to participate in the organization as much as I can. One finds oneself as a country-dweller, in regards to this issue, of being able to understand an organization or not understanding it, participating or not participating; being involved in daily life that says take care of yourself and get ahead, or share a space with other people. But fine, in the end, you end up resolving the issue of being able to fight for what one believes, for the life that one wants to lead, feeling that there are others who think the same in a world where one always meets people who do not think the same way, or do not want to defend the same way of life. And, well, to be able to find people like Yanet, like Pedro, like so many others who generally believe the same things -- in defending the country life and all that it involves -- that is gratifying. In Motion Magazine: Thank you. Pedro Huayquillan: Well, my name is Pedro Huayquillan. I am a member of the Huayquillan community in Colipilli Park. I am native to the Mapuche community here in the north zone. Our commitment to be here, to participate in these meetings, is simply that they listen, above all, that the authorities who have the responsibility, that they listen, and improve the herding area through which our communities and our people travel each year in this province. For that reason, today, our commitment is to be here and to also be clear on this, on the demands we are making. No? Above all to recover our ancient trails, to be able to travel them, I believe, safely, and above all else, securely and in peace. Those two things. To be clear on that so that the current government listen to us and, above all, continue working with us. No? So that the herding trails be maintained. (And) the whole culture -- I believe that the Mapuche people, I believe that they make their livelihood from the herding of the animals, from the animals. Herders are the majority in the community where I live. Before, the herder used to suffer less; that is, his life was more tranquil. Today, I believe that there are two problems. No? Because we know that presently we travel the routes that vehicles also travel, which for us is not at all comfortable. In the past, it wasn’t done this way; but rather it was all done naturally. Today, it takes longer to arrive at the place where the summer pasture is because it is necessary to travel the route with all the inconveniences that are put upon not only the herder but also the car driver. It’s a big problem, listen, and we don’t want this to continue. We don’t want it to continue to be maintained in this way, because we want our (herding) drive to travel freely. That’s why we’re here, with the commitment that one day this will be a reality. We as Mapuche, I believe in olden times we had another life, a life that was in harmony with nature. The Mapuche people didn’t drink; the people lived in harmony with nature. I believe that here in the province of Neuquén, our Mapuche people lived with the wild animals, such as the guanaco (similar to the llama, but larger in size), the rhea, as everything that is found in nature, the pichi (a dwarf armadillo), everything that is rarely seen today. After the Desert Campaign, (editor’s note: The Desert Campaign (1833-1834) and the Conquest of the Desert (1870s and 1880s) were military campaigns against the Indigenous peoples of Patagonia in Argentina.) obviously, as that changed the life of the people, our struggle began. And life totally changed. It changed in the sense that life involved more suffering. And for that reason we continue resisting. We continue saying we are here and we have a responsibility, today, to continue struggling with the Criollos (the people of European descent) who are going through the same situation as us. Today, with the same problem, the matter of land, we also are going through something that unites us, for example, to our Mother Earth. In Motion Magazine: How many people are in your community? In Motion Magazine: 500? Pedro Huayquillan: Yes and we have an area of more or less, including winter and summer pasture, of 15,900 hectares. In Motion Magazine: Can you speak a little more about the connection of the community to the land and to nature? Pedro Huayquillan: Those are a pair. We are a part of nature. I believe that we have a permanent relationship with nature. Because of that we are still here. I believe we are children of the land. And everything that surrounds us, we sense satisfaction with it, because all of nature that exists, we respect it, we take care of it, and we preserve it because we feel that it is our land. (But) Everything that there is today, and that which is happening, is clearly a product of man. Why is it that times are getting bad? It’s because man is contaminating everything, he’s changing everything. Right? For example, the weather, each year is even drier, each time there is less water -- well that is a product of man. It is not a product of nature. (It is) because we are not becoming conscious of this. If we were to permanently become aware of this, we would feel loved by our Earth. In Motion Magazine: Is your community connected with other parts of the Mapuche people? Pedro Huayquillan: Yes the vision of respecting our Ñuque Mapu, our Mother Earth, in that we all agree. In fact, Indigenous people always point that out -- to respect nature, which gives us everything.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2017 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |