|

Interview with Francisca Rodriguez

Part 2 / English | Español Part 1: Making Visible the Work and Participation of Women This interview was conducted (and later translated and edited) by Nic Paget-Clarke for In Motion Magazine on October 18, 2014 in Santiago, Chile. Francisca Rodriguez is “... from here, from Lampa, which is a very large commune in the metropolitan region of Santiago. I belong to the National Association of Rural and Indigenous Women (ANAMURI). And I am one of the constituent members of La Vía Campesina, at the international level, and of CLOC (Coordinadora Latinoamericana de Organizaciones del Campo), which is the Latin American identity of Via Campesina.” Quick Links:

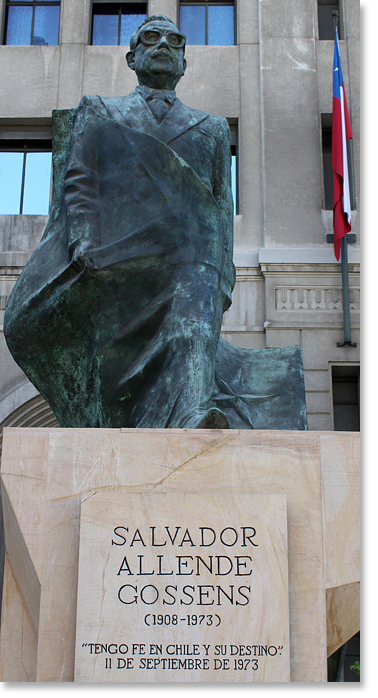

Organize both political and social movements In Motion Magazine: I understand that you were a part of the struggle against the (General Augusto) Pinochet and United States coup d’état in 1973. Can you please talk about the significance of the coup and the process afterwards? What were the roles of women and of Indigenous people? Francisca Rodríguez: To start with, we were young in those times. And we were constructing a great dream, which was to change the foundations of this society. And, in that political construction, the political youth played a big role in the success to create a government of the people. I believe that it has been the most important collective work of the people of Chile, to have constructed a program, a political proposal for a people’s government. And of course, because we clearly participated actively in the government, its overthrow was for us a hard blow. It was a very difficult repressive situation that we strongly lived through, during the military dictatorship and the raising of a clandestine operation. That is, the first stage was a clandestine task of rebuilding our political forces, political movements, and social organization. The Chile coup had a unique characteristic because its (purpose) was to not permit a popular government in Latin America, so, as a consequence, there was here a very strong political and organizational development. All the repression was directed against the parties of the left and the social organizations, primarily towards the workers’ organizations. There is a difference, for example, from the coup d’état in Argentina, which was very much directed towards intellectualism; this was very much directed towards the popular sectors. That meant for us to seek out the ways to reconstruct [the] movement, but also to reconstruct political forces. To once again reestablish those political links. And I believe that was one of the important points that the resistance in Chile had that we were able to organize political movements, but also to organize social movements. And those two elements permitted us to organize the anti-fascist resistance. Women were key in the resistance to the dictatorship On the one hand, the greatest repression was directed against the men, but (on the other hand) the most ferocious torture was done to the women, that is to say, they did not forgive the women involved in politics. Now, how was it that there was such a biased view, the point of view of the dictatorship, of thinking that we (women) were not thinking people, creative, capable of developing, evolving practical thought? Practically, the union and political governing bodies were decapitated -- many leaders were killed, imprisoned, persecuted. As a consequence, we the women took the primary political responsibility in the clandestine work, including the governing bodies of the Left parties, at their most decisive moments, were directed by women. And the very social movement, the very union movement, their most important actions were carried out by women. The organizing from the prisons was made possible primarily by the women as the connection between the public world, and the world of politics, from the external political world to the interior of the prisons -- by the women. That has been little recognized. So, we were key. We were tremendously important in that period of anti-fascist struggle, in the resistance to the dictatorship. So much so, that the most confrontational actions against the dictatorship were brought about precisely by the women from the Family Members of the Disappeared Detainees. Being spouses of the disappeared, activist women, women of the Left, they put themselves at the front of confrontation actions against the dictatorship. And, on the other hand, we were doing important activities for the big mobilizations that began for us on March 8, in the first year of the dictatorship. And it was very stimulating for the whole movement. I believe that for many women it made us mature all at once. Mature in a political sense; combining the public struggle with the clandestine struggle; being at the front confronting the police in the mobilizations and also, on the other hand, with this work on the inside of the prisons, that flowed from the women, that was conducted by the women, keeping alive the spirit of those who were imprisoned. So I believe that the role that the women played in the anti-fascist struggle, in the resistance against the dictatorship, in developing and setting up the political processes, were determinants for being able to advance the ending of that great pain which the military dictatorship meant to the people of Chile. Breaking the isolation of the countryside In Motion Magazine: When did ANAMURI begin? Francisca Rodríguez: Well, ANAMURI is a relatively young organization. It is 16 years old. It is young, but those of us who constitute it have many years of experience with the organization. ANAMURI is a product of this evolution of the development and the action of the women in the time of the dictatorship. It is during this period that the internal aspect of the peasant movement began to make visible the work and participation of the women. When the women came to the campesino movement, to the organizations, they didn’t come because they were seeking their rights, no. They came because they were looking for their husbands. And many women were living very close to Santiago but had never come to Santiago -- they had always been in the countryside. So, the dictatorship forced us, let’s say, to take a more protagonist role in the solidarity struggle. Solidarity was an important political tool during the time of the dictatorship. But also it broke the isolation of the countryside. Because, so you understand, the first measure that the military government took was precisely to declare the illegitimacy of agrarian reform. The worst crimes, the most atrocious, the most massive, occurred precisely in the countryside. Here, the country was sustained by an agrarian bourgeoisie that did not forgive the uprising, this struggle of the peasants for land. And then, a decree was promulgated which invalidated the agrarian reform law. It pushed many campesinos out of the countryside and many campesinos were imprisoned, “disappeared,” and the women, the only way that they had to find out about them was the organization. And they began to come to the organization in that way. I always say that among our men compañeros there were many fears, we women also had many, but many (men) shielded themselves behind us (women) in order to say that they were not able to participate because the women were very afraid. There was a female internal leader, a political activist, who asked us if we were able to invite the wives of the leaders, to convince them that regardless of the fear it was necessary to organize themselves so that they wouldn’t hold back their husbands from returning and occupying their places -- and to return to rebuild the organization. And we did that in ’79. And when we spoke with the women and various women came from different parts of the country, we realized one very important thing. It wasn’t that we were afraid. Yes, we were afraid, but our husbands were even more afraid so they hid behind us so they wouldn’t have to go and advance the process of recovering the peasant organization. And from that moment on, the need for organizing ourselves rose up within us. We realized that we had a space inside the organization. And we set up the women’s department of the organization. Along with that, we participated in the National Union Coordination Committee, in the women’s department. From there we developed many, many actions, many activities, and the organizational process of women in the countryside. Through the expulsion of the peasants, through the departure of the peasants from the countryside, women began to visualize their protagonist role from the point of view of production, and from the point of view of economic income for the sustaining of the family. And that strengthened the participation of women. However, in mixed (men and women) organizations, the traditional organizations, there were not more than one or two women in leadership. And since we were opinionated women who were in leadership, it appeared that the doors were closing so that others could enter. There was a fear that we would displace the men compañeros -- and that led us to setting up an organization of women. But it wasn’t only here in Chile. I believe that there was inspiration from other women. The Bartolina Sisa was already in Bolivia. The CONAMUCA (National Confederation of the Peasant Women) had risen up in the Dominican Republic. Already there was the movement of women peasants in Brazil. So, along with them we began to reconstruct these social movements in Latin America, with new strengths, with new forms of organization. Self-discovery of our struggle and resistance For us, the campaign about the 500 Years of Resistance by Indigenous people, by peasants, and Black people marked an important milestone in this new vision -- on one hand, in this new construction of social movements, but also in the construction of the political organization of peasants. In that process which lasted five years, when they wanted to do a five-year celebration here about the discovery of America, we launched a self-discovery five-year campaign of our struggle and resistance, and of the abilities of our peoples. We said that there is nothing to celebrate here. There are many things to reclaim. There are many processes that have to be restored, that have to be reconstructed. And for that we have to self-discover our abilities in struggle and resistance. This process that the Indigenous people and the peasants promote in Latin America is decisive for the formation of the new social movements. In other words, we the peasants at this stage made perhaps one the greatest historic contributions that was not written about, nor valued for all its significance. I believe that it costs us much to recognize our advances, our ability, our intelligence, our firmness in political decisions. And parallel to these 500-Year campaigns we were giving life to La Coordinadora Latinoamericana de Organizaciones del Campo/the Coordination of Latin American Organizations of the Countryside, or CLOC. From the campaign arose CLOC/La Vía Campesina, which is why the First Declaration of La Vía Campesina was created in Managua, in Nicaragua (and the following year, La Vía Campesina was established in Mons, in Belgium.) It is the product of this process that was being developed in Latin America. Unity emerged with a lot of strength but looking straight ahead. It was the path that the organization needed and required. And that is why we are a continental movement. We are not a federation. We are not a union. We are a movement, a coordination, a coordinated movement in Latin America. That is why La Vía Campesina is La Vía Campesina and is not the International Union, nor the International Confederation. It is a challenge from the peasants to establish an alternative to the neoliberal model. It gave us back our identity as producers In that process we were able to rescue our political proposals: a language that was demonized, which was “Satan-ized,” in that we were not able to speak of struggle; we were not able to speak of class; we were not able to speak about revolution; in which we were beginning to question the processes of the left, a lethargy towards socialism. We were capable of constructing a new political proposition step by step. I say a revolutionary proposition for our times that emerges at that precise moment which is the assault by capital to take control of the world’s food supply. In the first World Food Summit (editor: 1996, in Rome), when an action plan for peoples’ food security was proposed by the governments of the FAO (United Nations Food & Agriculture Organization) the strategy for food supply security was directed primarily to people having the resources to acquire foods. It was not directed at strengthening peasant processes for producing food, but to buy, to acquire food, to open wide a road for transnationals (corporations) -- granting them legal power over the food systems of the world and converting food into a commodity. It was at that precise moment that we, La Vía Campesina, raised our voices to say that this was not a security problem, it was a sovereignty problem. Starting with that process, looking at ourselves and how we were saying we were sovereign, we were converting sovereignty into a set of rights for the men and women in the countryside. And this process, birthed by the women in Latin America, was gaining strength, because food sovereignty gave us back our identity as producers in the important role we were playing in agriculture. It showed us that peasant agriculture has been maintained in various countries because as women we had resisted leaving the land. That very important process was generating a whole movement of women in Latin America, not only in Chile. That carried us, it encouraged us to break through the barriers that were present within the organizations of the peasant movement, and to generate organizations of women and in that context establish Anamuri. We are asked to silence ourselves The first declaration of Anamuri says that “we are in rebellion”. We were already in the process of returning to democracy. And, in the specific case of Chile, this democracy was very tied down, very controlled by the State Department up there in the North that imposed serious restrictions so that we couldn’t go back to instituting themes such as agrarian reform. During the first government of the Concertación (Coalition Government), President Patricio Alwyn asked us … In Motion Magazine: Concertación? Francisca Rodríguez: The Concertación was a coalition of parties (Concertación de Partidos por la Democracia/Coalition of Parties for Democracy) who coalesced to elect the president, the first president after the fall of the dictatorship, the first government after 18 years of dictatorship … to elect, we could say, to participate in the elections, and to present the candidate (Patricio) Alwyn who was the first president after the military coup. But this presidency asked that we put away some flags, that we hide them, that we not speak of matters that could be contentious because we had a very weak democracy. That we had a sword here to our head and that at any moment the military could return and give us a big blow. So, we were not able to speak of agrarian reform. We were not able to speak against the "agricultural development” (quote, unquote) that came with the arrival of the transnational companies in the countryside to implement monoculture production. We had restrictions on talking against what it meant, for example, to strongly denounce the approach of the production system and its consequences: the great danger in the use of pesticides; the effects we had from the pesticides, where we had already had a great number of sick workers, of children born with congenital deformities. So, we had a great battle against chemicals, all the chemical corporations. And the government was asking us to postpone all of these battles. In 1992 we made a video called Cuerpecitos de Niño (The Little Bodies of Children https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uTeLACtCAsk) in which we documented the children born with congenital deformities produced by agro-toxics. And our compañeros told us, "Please stop this campaign of terror." That for us was very hard, in other words, to come and tell us that by denouncing what that very day was so terrible and was affecting the people as a whole was a campaign of terror, from the mouths of our leaders, was more than we could take. And it was there that we decided that we were going to form an organization of women, so that they wouldn’t be able to silence us. And also, that we were not terrorists, that the terrorists were those that were presently stationed in the transnational corporations where human beings didn’t matter, only great profit. And they were presently, committing a massive crime. Because I believe that if we were to count the number of people who have died because of agro-toxics, because of the poisons, we would realize the number of people who have been killed by the chemical industry. It was there that we decided to form ANAMURI. We left the organizations, which is why we said that we left in rebellion to the cooptation processes that the government had over our organizations, in wanting to silence our voice, in wanting to quiet our denunciations. And thus with 52 women we formed the National Association of Rural and Indigenous Women (ANAMURI). The following year, at our first meeting, we were already more than a thousand women. We were growing, growing, growing. We travelled all over the country. We did not ask for a cent from the government. We relied on the solidarity of class. We went from organization to organization asking for help to form this organization and in a year we made a crazy program, well, we say we are crazy -- we are unstoppable women that do many things. In a year, we had held a discussion by sectors. The first meeting that we had was to discuss how we are going to work (function). It was called Con Cuerpo y Alma De Mujer (With the Body and Soul of Women), en Puerto Montt, in southern Chile. And that meeting brought us back to the land because up until that moment our main struggle was against agro-toxics and for the defense of women workers who had gone en masse to work in agro-industry and with the transnational corporations. That meeting was magic, that’s what we say, because we met many women in a territory in which there had not been done practically any agrarian reform; where the peasants’ roots were very strong, very intact. And this brought us back again to the land. It tethered us back to the land, to say that here we are to not only look at wage-earning women, but we also have to fight this great battle for food sovereignty, to recover the land, to make visible our work in agriculture, to have an appraisal of our economic contribution to the development of the country, and the maintenance of peasant families and their communities. I believe that was super important. And afterwards we had another meeting to speak about what were the programs that existed coming from the government, from this democratic government, for the women peasants, and we realized that the programs were insufficient because they didn’t talk about women peasant producers. (Rather) they had been talking about women to whom they wanted to teach a series of things for them to be better housewives And we destroyed that way of thinking in order to say, “No!” Here, we need to have access to the development of technology or to develop our own technology, the technology created by the campesinos, to develop them to make them more handy and more efficient. And we went in this great association in the direction of land and agriculture and food sovereignty. We went to see how our seeds were being lost. The seed campaign; the campaign against violence against women We had already joined with the women of Latin America. We had our first continental meeting in Brazil. We rose up with very clear proposals. We didn’t accept being just an individual part of the congress. We held earlier assemblies of women because we didn’t want to be put in the corner of the congress in the women’s commissions. So, we went about making a continental structure for women, a network of women of the countryside, where ANAMURI inserted itself and was strongly promoting the organization of the women of Latin America. This link with the women of other countries in the struggle is what strengthened ANAMURI and it’s what made us have a clear approach, firm, without vacillation, for food sovereignty, put forward not as the right of peasants to produce but as a joining of rights. The struggle for seeds, to declare that they (seeds) are our heritage, as Indigenous people and peasants, and we were putting them in service to humanity, they weren’t a heritage of humanity. That is to say, that it was a rich discussion, a very strong process that we women had made, that we had contributed (as well) to the political vision of La Vía Campesina. The principal campaigns that we women had proposed, from our discussion, without a doubt strengthened ANAMURI. Today, ANAMURI is one of the most important and emblematic organizations in Chile -- the only national women’s organization. It is the largest organization in Chile with a very clear plan. I believe that the strength that our organization has -- and that the other Latin American organizations of women have -- is that we have not allowed the peasant movement to isolate us. We are part of the peasant movement, which is why we established gender parity in La Vía Campesina -- and that has strengthened the peasant movement. For this reason we have launched a campaign for an end to violence against women in the countryside. Not only domestic violence, but also the violence that the system presently has in all its aspects: violence at work; in the environment; the violence in relation to the treatment of our Mother Earth, and all our natural resources -- the violence in depriving female and male peasants of our identity. The violence that there is when they want to deprive us of our knowledge, our wisdom, and our practices in agriculture. That is why we have launched, as I was telling you, along with our seed campaign, the campaign against violence against women of the countryside. Human thought, not capital thought We have strongly promoted the issues of agriculture, of agroecology. Not as something new, which is emerging, but the recovery of our ancestral practices in the working of agriculture. Those (ways) that have been brought forth and developed from the original peoples up until now – of all the science that has taken place in the development of agriculture. Yes, the first geneticists were the Indigenous peoples and the peasants. And they didn’t have to go to university to receive a title. But it has been the most valuable contribution that there has ever been. That I believe is the strength not only of ANAMURI but of the integrated women’s movement in Latin America, coordinated through La Vía Campesina with the women of the world. In other words, wherever you go you are going to find women organizing, you are going to find them fighting, you are going to find them resisting, because the women of the countryside we have created an impressive force; before, we used to asked city women to support us, and today, the city women ask us women of the countryside to support them because we have a very strong identity with the land; because we have given a very great value to our culture; because we have been recognized for our knowledge and wisdom; because we have the ability to think and to propose; not only reclaiming, not only demanding, we propose and we construct alternatives. These are modern times. Of course we strongly combat technology, but we use technology. We speak of a science and a technology in service to the people that today is in service to capital. A technology directed specifically to move us away from social life; a technology that tends to isolate us and to consume us. We want a technology that connects us, but connects us in terms of human thought and not capital thought, which today is predominant in the world. That is what we women are.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2017 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |