|

Combatting Monsanto

Grassroots resistance to the corporate power of agribusiness in the era of the ‘green economy’ and a changing climate" by Joseph Zacune with contributions from activists around the world La Via Campesina, Friends of the Earth International, Combat Monsanto

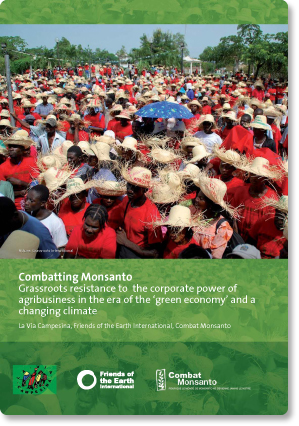

This report provides snapshots of frontline struggles against Monsanto and other biotech corporations pushing genetically modified (GM) crops.(1) It shows that small-holder and organic farmers, local communities and social movements around the world are resisting and rejecting Monsanto, and the agro-industrial model that it represents. There is intense opposition to this powerful transnational company, which peddles its GM products seemingly without regard for the associated social and environmental costs. These vocal objections from social movements and civil society organisations are now having an impact on policy-makers tasked with regulating the food and agricultural sectors in relation to GM crops and pesticides, as this report demonstrates. In India, for example, a moratorium has been implemented on the cultivation of Bt brinjal, a GM version of a key Indian food staple, and Mahyco-Monsanto has been formally accused of biopiracy by India’s National Biodiversity Authority. After a decade of popular opposition in India, a movement rejecting Monsanto’s colonial-style approach is gathering under the ‘Monsanto, Quit India!’ banner, with a view to ejecting the company from the country. This would free India’s cotton industry of Monsanto’s current stranglehold, and help to stop the suicides of small farmers driven into debt by the ever-increasing costs of GM and chemical inputs. The movement against Monsanto is also growing in Latin America and the Caribbean. The powerful farmers’ movement in Brazil continues to promote alternative food sovereignty initiatives; and mass mobilisations in Haiti roundly rejected Monsanto’s hybrid seed ‘donations’ after the Haitian earthquake, because of the threats this ‘assistance’ would pose to small farmers and food sovereignty in the country. A ten-year moratorium on GMOs has been introduced in Peru, and legal cases now restrict pesticide use near homes in regions in Argentina. Guatemalan anti-GM networks are issuing warnings against impending legislation and about US aid programs that could lead to the entry of GM seeds and food. The majority of Europe’s public remains opposed to GM food production, and several countries in Europe now have national bans on Monsanto’s MON810 maize and BASF’s Amflora potatoes, despite the European Commission’s opposition to these bans. A range of direct actions continue as well, including France’s ‘voluntary reapers’ protecting local food production, and Spain’s activists raising public awareness of the Spanish government’s isolated support for GM crops. Anti-GM actors still face many challenges though, in France and elsewhere. These include food crop trials, moves to undermine existing moratoria in Europe, and aggressive tactics being deployed by the industrial food lobby. This also involves using the French and EU courts to have the French ban on Monsanto’s MON810 maize overturned,(2) although the French government has since announced that it intends to maintain the ban anyway.(3) Monsanto and other biotech corporations are also facing legal challenges in the US, including lawsuits aimed at stopping GM crops spreading into national wildlife refuges. The Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa is encouraging local communities to avoid the bad example currently being set by South Africa, which has adopted this failed technology even though the GM varieties in question have been shown not to live up to claims that they are drought and flood resistant. Malian farmers and NGOs are also continuing their struggle - which has been successful so far - to prevent the commercialisation of GM crops in Mali. In every continent then, communities are fighting against GMOs and for food sovereignty. Yet there is an unprecedented agribusiness offensive underway, under the banner of the new ‘green economy’, a concept that is – in the run up to Rio+20 – being framed with a view to creating an even greater role for corporations and markets. This could allow agribusiness, including Monsanto, to reassert and tighten its grip on food and farming, and facilitate the spread of genetic engineering – worsening the food and climate crises. It is thus hoped that the testimonies and analysis contained in this report will be heard and heeded by those who define the ways in which environmental protection and sustainability are managed, as well as inspiring and uniting those consumers, activists and movements already determined to dismantle Monsanto’s power. Policy-makers must take a new approach: by empowering local communities, sustainable initiatives can render GM crops, pesticides and other agribusiness practices obsolete. The use of GM crops destroys essential crop diversity, homogenises food, and eradicates associated local knowledge and culture. In this and other ways social inequality, poverty and the exploitation of natural resources are able to thrive within the existing neoliberal capitalist food system, which focuses on profit generation rather than sustainable food production. Yet food sovereignty is a real and feasible alternative. It is not purely for agricultural communities but a practice that needs to be integrated into a wider approach to developing sustainable food systems. Bringing together those struggling against Monsanto specifically and those challenging agribusiness in general will help us to develop common goals and a shared vision with which we can transform our societies. Now is the time to act against Monsanto.

Monsanto – the leading source of genetically modified (GM) crops(5) – has its headquarters in Missouri, USA, and over 400 facilities in 66 countries. It generated net sales that amounted to more than US$11.8 billion in 2011.(6) The Monsanto enterprise was originally founded in 1901 as a company manufacturing chemicals. As it grew, Monsanto started producing sweeteners for food companies, agricultural chemicals including DDT,(7) toxic PCBs(8) for industries, components of Agent Orange(9) for the military, and bovine growth hormone.(10) In the 1980s and 1990s, Monsanto reinvented itself by focusing on genetic modification processes. This shift was consolidated as GM crops became commercialised in the mid-1990s, and the global sale of seeds became dominated by Monsanto as it bought up major seed companies.(11) By 2005, Monsanto was the world’s largest seed company, providing the technology for 90% of GM crops around the world.(12) Monsanto controls 27% of the commercial seed market.(13) It controls 90% of the seed market for soy.(14) However, the application of the genetic modification process has been confined to a limited number of commercial crops such as soy, maize and cotton. Monsanto’s control over seed varieties has been bolstered by its aggressive implementation of patent rights: it frequently compels farmers who purchase its patented seeds to sign agreements that ban them from saving seeds and replanting them. Farmers breaking this agreement can face legal action. Despite becoming a leader in the development of GM traits, only two main gene traits have resulted in significant commercial production over the last sixteen years: herbicide tolerance and insect resistance.(15) Specifically, the majority of Monsanto’s GM seed varieties have been developed to be compatible with the company’s glyphosate-based Roundup herbicide sprays. However, this bestselling herbicide is linked to serious illnesses and birth defects: communities living in the vicinity of monoculture GM crop plantations have been blighted with poisoned lands and major health problems.(16) Monsanto and other agribusiness corporations also claim that GM crops are a solution to hunger, carbon storage and the effects of climate change including drought and flooding – even though trials have repeatedly failed. Analysis has shown that there is no evidence that GM crops produce greater yields than conventional crops,(18) and there are no ‘miracle’ crops available that tolerate drought,(19) flooding or salt. Neither do GM crops store more carbon in soils due to decreased tillage or the ‘no-till’ techniques associated with GM crops and pesticides.(20) What has happened though, rather than solving hunger, is that the corporate grip on agriculture has tightened as we head towards one billion people going hungry globally.(21) GM worldwide: few crops and limited to a handful of countries In 1996, the US was the first country to significantly cultivate GM crops for commercial use. A decade later, just 80 million hectares were devoted to GM crops worldwide, the vast majority in the US, followed by Argentina and Canada.(22) Today, according to the pro-biotech industry body, ISAAA, GM crop cultivation has increased and in 2010 occupied 148 million hectares(23) out of the total area of global agricultural land, which is 4.9 billion hectares.(24) Therefore, the combined area of all GM crops covers just 3% of agricultural land worldwide. 97% of agricultural land around the world remains GM-free. GM crop cultivation is predominantly limited to a few countries: 90% of GM crops are grown in the US, Brazil, Argentina, India and Canada.(25) Almost 60% of GM crop field trials are carried out in the US.(26) The large majority of GM crops are grown for animal feed or agrofuels destined for rich nations rather than food for the poor and hungry. La Via Campesina coined the term ‘food sovereignty’ in 1996 to advocate a model of peasant-based, sustainable, agroecological farming. Since then it has become a vital concept that reflects the practices of communities around the world. Food sovereignty is the right of all peoples to produce and consume healthy and culturally appropriate food which has been produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods. It is also their right to define and own their own food and agriculture systems. Food sovereignty puts those who produce, distribute and consume food at the heart of food systems and policies, rather than forcing those systems to bend to the demands of markets and corporations. It defends the interests and the inclusion of the next generation. It offers an alternative to the current trade and food regime, and promotes food, farming, pastoral and fisheries systems that are determined by local producers. Food sovereignty prioritises local and national economies and markets that empower peasant and small-scale sustainable farmer-driven agriculture, artisanal fishing, and pastoralist-led grazing. The Nyeleni Forum on Food Sovereignty in Mali, in 2007, was a milestone in the movement’s progress, when peasant farmers, environmentalists, pastoralists, fisherfolk, indigenous peoples, agricultural and industrial workers, women, youth and urban consumer groups came together to consolidate their efforts. Also read:

|

||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2018 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |