|

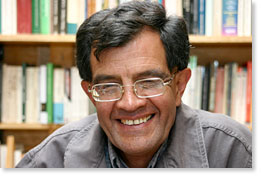

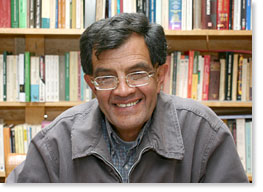

Interview with Raymundo Sánchez Barraza

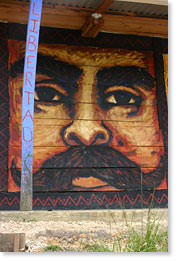

A University Without Shoes An Indigenous Intercultural System of Informal Education San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico

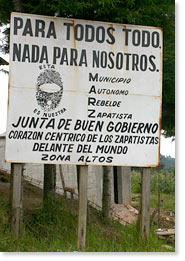

In Motion Magazine: Please tell me about CIDECI and your role here. Raymundo Sánchez Barraza: Raymundo Sánchez Barraza, at your service. My work here is as General Coordinator of a program which would like to be a system, a system which we call the Indigenous Intercultural System of Informal Education. My job is coordinating all the parts of this system. We’ve been working here since 1983, and we’ve gone through different stages in that work. We consider this program to be more like one whose profile, face, has been taking shape sequentially, and, as I said, it’s been going through different phases, different stages. The first component of this system is just that, what we call CIDECI Las Casas. What does CIDECI Las Casas mean? It means the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Comprehensive Indigenous Training Center. It’s an Indigenous Center. This is what makes it significant and what gives it its unique characteristics. It’s not a center that’s just for, but it’s also by, the indigenous. It’s an indigenous center in its work, in its definition, in its method of operating, in its components, in those who make it up. This center began on August 24, 1989, sixteen years ago. It was called Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas, because we began on August 24 of that year and the San Bartolomé fiesta is celebrated on August 24, which is the anniversary of the birth of Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas. As I already told you, we positioned ourselves from the beginning on the margins of prophetic critique, vis-à-vis history, vis-à-vis the world, vis-à-vis the demands of the minorities, the despised, conquered peoples, in this particular case, the peoples of Mesoamerica, the demands and struggles of the Indian peoples. Out of principle, we adopted the political view of radical democracy. At that time we said that we have to transform the Nation State, along with the entirety of its institutions and relationships, and, therefore, we want nothing to do with the State. Since 1989, we have said “no” to established political power. We have to work from below with the forces of society, taking tiny steps, in order to regain the capacity for self-determination by that hypostasis which is the State. But we also said that we aren’t going to set ourselves up as a counter-power, because we’ve seen that the construct of power is the same when counter-power is established. Now, what were the key concepts, aside from these, which fueled the initiative? One was this: we have to turn our gaze backwards. We have to see when this historic system, that we know today as a world system, was first created and established. And we said that this world started to be established with an expansion which involved mechanisms of domination in the clash of the discovery and of the subjection of the peoples of America. There we have the hallmark of this world system we have today, and we asked what it is that allows some peoples, despite this clash, to survive. We began looking at some experiences from the 19th century here in our country, and in other places in Latin America, which allowed people to survive and to resist, maintaining their identity. Not without contradictions, but we can see that, after 500 years, those people exist. Those people don’t speak, (yet) they have their own language. Those people still have key components of their world vision and of their way of naming and seeing the world. We looked at Vasco de Quiroga’s experience with the hospitals of Santa Fé, with the peoples around the Patzcuaro Lake. Vasco de Quiroga was inspired by Thomas More’s utopia. And then we looked at the Jesuit settlements in Paraguay, in southern Brazil, in northern Argentina, in Bolivia. How these initiatives, from the West itself, in that utopian vein, allowed these peoples to resist to a certain extent, to maintain themselves, not to lose the fulcrum of a basic referent of their identity. We said, we have something to learn here, and that concept we learned here was resisting and surviving. But that was in the ’80s, and there was already a lot of literature which distanced itself from the large projects being concocted by corporations, by the State, by the interstate system, by the United Nations. We started seeing that the great concepts of this Western modernity could be subjected to a radical critique. The concept of development, the concept of formal democracy, the concept of the market, the concept of poverty, the concept of equality. Then, we got hold of the Illichistas, the people who follow Ivan Illich’s great intuitions and method of critical reasoning, the Mexican Illichistas. That’s why I’m such a good friend of Gustavo Esteva, for sending all these concepts to the obituaries and for then making the radical statement that this is an historic system. What we see is that this system has to come to an end like others have. Hope, therefore, belongs to the resistance, but it’s the hope that something else is possible and that, even though we’re immersed in the contradictions of the world, in some details of our dealings, our work, our thought, our seeing, you have to realize that we’re going by another path, not by this world’s path with its model of profits, marketing, exploitation, greed, control, contempt for the different. That was how this idea came about, from those two factors -- the resistance that those 16th century utopians taught us and the critical factor of the rupture of illusions, of being critical, the critical archeology of the dominant concepts of modernity, and from those peoples who resist. Accompanying them in order to reinforce their cognitive, organizational, and practical ability to resist. In hopes of what? That another world is possible. That we won’t fall into the trap of those who tell us that what exists is inevitable destiny, there’s nothing else. We say there is, we’re seeking it. We want to build it even though we have to prepare for great disasters, getting on a little boat that’s like Noah’s ark, tiny. With whom? With those who have resisted for centuries. Who are they? These peoples. Surviving, resisting: a university without shoes That’s the first component. We just teach little things for surviving and for resisting, but then we took another step, Nic. After expanding this idea horizontally, after having seen that we couldn’t sustain this concrete idea - which worked, which walked – because there weren’t any resources, especially if we didn’t want to depend on the State, we made a virtue of necessity. We had delivered the centers, and we said now we have to take another tiny step, and, in an act of self-determination, we also asked why, if knowledge is being produced and disseminated here, then aren’t we a university too? A university without shoes, of course, a shoeless university just from below. But this knowledge has prestige too. We have to expropriate those who monopolize the prestige of knowledge and expression. We too are a university which has knowledge. We can draw up study plans in order to accredit this kind of profession, which will still keep them close to the earth, in the service of others, and which will allow them to strengthen their habitat in order to survive, to resist. That is the second step. And now we have our courses. We have our study plans. We have our curriculum, of course. But we’re building everything from below with what we have here, by combining certain skills, certain modules, certain workshops. We can guarantee that someone who learns construction metalwork, carpentry, electric work, technical drawings, architectural drawings, computing, AutoCAD can become a vernacular architect. With what is fitting, characteristic of what still exists, mesoscopic, along the lines of what you can see, touch, not the macro nor the infinite, but the micro, the mezo. That which is our size and of our dimensions. Agroecology, as well as the administration of community initiatives, hydro-topography, surveying plots, designing water systems, channeling water without provoking it, without those large dams holding it back so it can then destroy us. Whether the world is going to survive Then, we said, now we have to turn it around. The university system is a Western invention, the school system, just like the formal. Now -- from where we are and with our identity -- we are going to invite you, come, from this space. You see them as poor and you see them as limited. We too can think great thoughts. We invited them to a seminar at our Center of Intercultural Studies, because this issue -- whether the world is going to survive -- is a great issue for the present and the future, but in a radical way, Nic, ground zero of our world vision. Beyond dialectical dialogue as a mechanism for exchanging arguments, points of view, is the dimension of the ineffable meeting with the other, here, where I can’t dominate him, subjugate him, or make him feel less than me. Here, we’re hand in hand with Gustavo (Gustavo Esteva) of the Center for Intercultural Meetings and Dialogue of Oaxaca. Hand in hand with the Intercultural Institute, Robert Masho’s, the one in Montreal, in Quebec. And hand in hand with the work of their teacher, Raimón Pannikar. We’re hand in hand there. Here we have a tiny seminary, an academy, and if we’re a university then we have to be one, reflecting on these great issues which, in my opinion, are issues of the present and the future. To understand this EZLN movement But there’s still something else, Nic. We’ve established this Imanuel Wallerstein Center of Studies, Information and Documentation as a fourth component of the system. I pronounce it the German way. I know he’s North American, but I pronounce it in German. Why a Professor Wallerstein Center here? I think analyzing the world system using the methodology and theoretical corpus that those who are in that current of the social sciences have been producing -- especially Professor Wallerstein’s contributions -- is very useful for understanding the world as a world system. This theoretical and methodological scheme has helped us a lot, Nic, a lot, to understand our circumstances, our regional and national circumstances, and the world context. But more than the world context, above all, to understand this EZLN movement from a perspective that we lose sight of when we look at it just locally. Here we have a seminary of studies. We study Professor Wallerstein’s work. We have our seminary, and people come from organizations here in San Cristóbal, Comitán and Tuxtla. Some university teachers come who want to know what it’s about. You know Professor Wallerstein came. He was with us this last June 23 and 24, and he presented a book which we’ve already published as CIDECI Unitierra Chiapas. There’s a book which is called The Structural Crisis of Capitalism which we’ve published. In my opinion, this perspective is very important because, listen, I’ve known the work for more than 20 years, and I’ve been producing it and following it little by little. Right now his works, or a good number of them, have been translated into Spanish. But look, the key approach is this, like we said a minute ago, they say nothing can be done anywhere in this globalized world, since the Berlin Wall fell, since the Soviet Union disappeared. What comes next is what there is. There’s nothing for you to do but adapt to globalization and take up the great issues and see if you can still heal this world a bit from all you’ve done to destroy it. But there are others of us who say no. If this is an historic system, and for the first time it’s an historic system with a world economy, then it’s historic, and I have to look at its indicators, not just its development, but the indicators of its limits. I believe this system has reached its secular limits and the indicators we have of crisis, of disorder, of entropy, are the indicators of a terminal crisis. That’s what we’re experiencing. If you look at the world from that angle and look at what we’re doing, then what we’re doing is valid. We’re in the future, and we’re sounding an alert because we also believe that the critical fluctuations over the next few years will be such that they’ll collide with catastrophe. Look at New Orleans, it’s a horrific mirror, even of this size. It’s a horrific mirror of what awaits us. But we said we still needed more, which is why we have the University Center of Open and Distance Education. We said we would take the concept that you can learn forever seriously. We took seriously the concept that knowledge has to be free, that it’s not necessarily in a classroom, with a blackboard. That’s a format which has developed historically, but it’s not the only way. The learning that really lasts is meaningful learning, learning which bursts forth in the dynamic of self-learning. Let us still do it with books, because books are an instrument of culture, a great way of reversing time and of talking with Kant, or with Hegel, or with whomever, or with the great declarations of the Mayan culture. Why does this have to be lost? We’re not against the Internet or computers. We’re not against them, but here we want this to be mediated by books, not favoring online. Because right now, Nic, everything is being sold online, diplomas, teaching certificates, doctorates, this, the other, magazines. So, we don’t want people to be in those circumstances. We want them to have the pleasure of learning what isn’t in the market yet, philosophy, literature, educational sciences, theology, what’s not in the market. But because it’s not in the market, it acquires a weight since it’s in such tremendous oblivion. We’re looking for those who can understand this project and say, “Why not, I’m with you.” And we found that in Bogotá, in Colombia with the San Tomás University. Who are we thinking about? About the young adult indigenous who are in their communities and who can’t pay to be at university but who want to want to follow what the University is doing. Those who want to have the pleasure of learning what they want, without it being tied to work or a profession. The pure freedom of learning and for someone to accredit them with a prestigious title, even though the State doesn’t officially recognize them. What a special kind of alienation we’re experiencing when the kingdom of liberty, personal education, has to be accredited by the State in order to know whether it’s of any use or not. We now have a general agreement signed, a specific agreement. I believe that if we define the question of fees in October now, we’ll be operating in January with philosophy in different specialties, with education sciences, with administrative questions. We want to look at theology, law, religious sciences with them. We’re not interested in market courses. We’re interested in separating what you learn from what’s going to be useful for you in your job. In Motion Magazine: How many students are here? Raymundo Sánchez Barraza: In one year, the records we have allow us to serve between 800 and 900 students. The ratio of men to women is still two to one. There are approximately some 4 to 500 men and some 300 women. Now, look, the system is open and flexible. It’s not organized like those systems with little energy, with enrollments. This is always open, and it always operates. Someone can come for 15 days, for a month. For three months, for nine months, for a year. It depends on their interest, available time. We don’t know when people, when young people, have time available. But there are between 800 and 900 a year, without counting those who come from the city, because there are people from the developments who come in the morning or in the afternoon; because the day is divided into four parts: from 9 to 12, from 12 to 2, from 4 to 7 and from 8 to 9. The boarders, the ones who live here, who eat here, who have their places to sleep here, who work here, plan their schedule by combining the four spaces, four periods. If he comes from a development in a barrio, he chooses the morning or the afternoon, since the night is just for the boarders. The ages vary from 12 years to 24 or 25. The median population is between 16 and 18 years. It’s a critical age for young people in the community, before they form their families and take on the responsibilities appropriate for being an adult in their communities. The population we favor is that of indigenous youth, women and men, who don’t have schooling or, if they did, it was cut off. They left without finishing, because to come here, with this exception, we don’t ask the young people for any formal educational requirements. The pedagogical principle which has directed our work from the beginning is learning to do, then learning to learn, and then the profound formative part: considering the other in his entirety, learning to be more. In Motion Magazine: Do the students from the developments have to pay? Raymundo Sánchez Barraza: Look, we’re counter-current, Nic. Those are the currents, we are against. We are, I believe, the only ones in this area who are so small, but we’re going against the dominant current. What is the dominant current? Everything is marketed, everything has a price, everything is bought and sold -- organs, the body, genomes, even the soul. We say that everything of ours is free. Of course, in order for it to be free in this contradictory world, you have to look for those who freely help this initiative. Not that we don’t ask for reciprocity, Nic. The young person who comes all day Saturday, from the morning until two in the afternoon, works by maintaining everything, clearing trails, putting in windows, painting here, doing something there, planting little trees, reforesting, gathering wood and all the basic cleaning services, taking care of the door, inspecting the latrines. Participating in the kitchen. In Motion Magazine: All the students? Raymundo Sánchez Barraza: All, for free. What would be fitting? Reciprocity, but we’re counter-current. Look, we don’t charge for anything here. Neither do we prepare for the market. Nic, neither, what the businessmen do, what the State does. We tell you that we’re preparing them for returning to the community. We don’t always win, we lose, but we’re preparing for their return even if it’s a year or two or three. The young person returns and contributes his potential to his community and to his organization. How do we do it? With a system of lures, small projects, the young person achieves his level of excellence. The level of excellence in his preparation, carpentry, metalwork, this, the other. He can have help one to one, which his family contributes, which we provide for free, so he can begin developing what he learned here in his community. A bakery, a tailor shop, a small carpentry business, an electrical workshop. That’s the way we try to ensure that the young person doesn’t go away, that he returns. Sometimes we win, sometimes we lose. That’s the way the world is -- what are you going to do? But, like the brothers say, everything is struggle, everything must be achieved through effort. Everything is struggle. The panorama of the Zapatista struggle In Motion Magazine: Speaking of struggle, do you have any contact or connection with the Zapatistas? Raymundo Sánchez Barraza: There is an elective affinity which is undisputed. We couldn’t do all this. This here is, in a certain way, anomalous. Let me explain. All of this could only be done within the panorama of what the Zapatista struggle has been able to open up: autonomy, self-determination, radical democracy, no to party politics, no to taking power. You don’t even have to ask us, Nic, those who feel attracted by a place like this, those who struggle, those who resist, those who say the rights and cultures of the people should be recognized. What amazes me about this Sixth Declaration, and gives me much pleasure, is that it has clearly defined itself as the most important, new style, anti-system movement in the world. Non-electoral, non-partisan, no to taking power. Yes to the affirmation of the left, but to the left after the fall of the Berlin Wall and disappearance of the Soviet Union. What is that left? Anti-capitalism is saying that the way this world is isn’t the one we want. What is to follow? That we have to win. It’s not the dictatorship of the proletariat, nor is it the inevitability of progress. No, we have to struggle to see that it’s more free, more egalitarian, more just. That is the path they are on. We’re not fighting them for anything at all, because the path we’re on, which we have been on and which we’ve been defending, is the same path. And we understand that on that path we have to till the earth, fertilize it, that we are the ones who are accompanying in that process, even if it falls to us to be compost, just the ones of below. Even if we’re not seen, it doesn’t matter. That’s how it is, Nic. It’s quite clear. In Motion Magazine: Is there a connection between the efforts to use agroecology and the struggle for democracy? Raymundo Sánchez Barraza: It’s like that for me, but here, our way is that we’re more engaged in this search for identity. The peoples are beginning to realize that all the technological schemes of modern agriculture break down their image of the land. They violate it, they mistreat it. Then, now, on this path of their dynamics of present-day culture, they’re beginning to see the land, to feel it again and to experience it like a mother, holy mother earth. They are beginning to discover this -- not because of technological arguments, not hardly -- but because of this profound affinity. Their mythic world vision of agroecology really is what helps them treat the land the way they profoundly believe it to be, which is as holy, as mother. What amazes me, after 20 years of working on this, is that there are communities right now, groups of producers, who look at agroecology not because you convince them technologically, but because they say the land is to be respected, cared for, nurtured. We ask permission to use it so it can continue to exist: the land and the men and women of maize which we want to be. There’s a tremendous affinity, beyond strictly intellectual and technological arguments. That’s what I began to see. It’s beginning to grow among the people and in the communities. And the rejection of all the technological packets of modern agriculture, this movement is beginning. It makes sense, Nic, when you look at it, if you look at the world like a world in crisis and in a crisis of civilization. Agroecology is an instrument of survival, and the people see that. They begin seeing it as what will allow them to treat the land as it should be treated: land as holy and as mother. Environmental education: ecological, organic In Motion Magazine: Do farm workers study here? Raymundo Sánchez Barraza: We work with young people. When a group of adults come, for example, there’s a group from Las Margaritas now, they thought about it and then they asked us for a course on organic agriculture, for adults now. They told us they couldn’t stay for a month or two months or three months like the young people. They wanted a special short course for 15 days on this subject, and they named their representatives. Twenty representatives came from 20 communities, and their short course was organized. That’s how we do it with the adults. They’re specific responses to the adults’ specific demands. For the young people, it’s every Saturday. If a young person goes just to technical workshop activities, he can have just agricultural activities on Saturdays so he can balance the subject and so he can begin discovering, gently, without being aware of it, what agroecology and organic agriculture are. But naturally. There are the ducks. Here’s reforestation. Up there are the lambs, the rabbits, the hens, the colotes (large baskets for storing maize). Everything exists, and everything has its little path, in such a fashion that living here is environmental education, because everyone begins to see where they live elements being intersected by the ecological, the organic. The Zapatistas in their different caracoles -- you well know -- a focal point of their work for years has been just this, agroecology. More than in resolving a functional problem In Motion Magazine: Do you teach the arts? Raymundo Sánchez Barraza: They are the arts in their pre-Renaissance sense. Not art as the expression of high culture, but art as a means of using the material to solve problems and needs. This is an art. Making a little cushion, making fabric is an art. Designing pieces of wood to use them as a shelf is an art. Working that piece of stone to make the Saint Francisco of Assisi is an art. That’s what we’re referring to. Making an ashtray, but designing it, putting elements of Mayan culture into it, is an art. Making this desk is an art; carving this is an art. The person who works in metal, for example, looks at the protective qualities of the metal. But someone working in metal should look not just to the functional, but, along with the functional, to what seems beautiful to him. We insist on that a lot. Not just in solving the problem, but that it’s seen to be beautiful. As another example, Nic, the electricians choose those light bulbs because they save energy, they save light, but the point is that, even though you’re going to use something functional, you try to adapt the space so that it’s beautiful. That’s what our art is -- not something specific, but you have to find pleasure in everything you do, so that it’s part of the habitat where you feel pleasure and you feel pleasure because you see it as clean, beautiful. The art is what you put in, more than in resolving a functional problem. Right, Nic? In Motion Magazine: How do young people find out they can come here? Raymundo Sánchez Barraza: We favor the oral, the word. This is our strategic plan. But for this strategic plan to be understood, I have to talk to you. In Motion Magazine: Most of the students are from the city? Raymundo Sánchez Barraza: No. In Motion Magazine: What languages do the students speak? Raymundo Sánchez Barraza: Here we have the Tzotzil, Tzeltal, Chol and Tojolabal languages. In Motion Magazine: Do students learn in all these languages here? Raymundo Sánchez Barraza: Here Spanish is the language that allows intercultural exchange, but they come from all parts of Chiapas. Sometimes youngsters have come from Guatemala, sometimes they’ve come from Oaxaca, sometimes from Yucatan. In Motion Magazine: But they are all indigenous? Raymundo Sánchez Barraza: The primary component, as I told you, based on a principle which gives this place its identity, its form, its destiny, is the indigenous, and the non-indigenous is stated clearly here to be the opposite. In the outside world, you are here, and they are there. Here it’s the opposite, they are the ones in first place. Published in In Motion Magazine December 18, 2005 Also see these 2010 PDFs from CIDECI: Also see:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2018 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |