Corporate livestock factories' self-serving

contracts, tax breaks, market-monopolizing

strategy and few local purchases

Economic Disaster

Boom or bust?

by Patty Cantrell, Rhonda Perry & Paul Sturtz

Columbia, Missouri

This article is taken from the just-released Missouri Rural Crisis Center publication Hog Wars - The Corporate Grab for Control of the Hog Industry and How Citizens are Fighting Back.

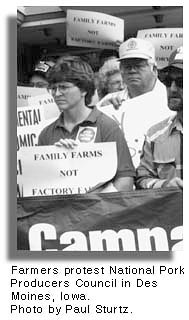

Corporate livestock factories tout themselves as messiahs to the rural communities they target. They promise salvation for everyone: Job creation for local citizens. Increasing tax revenues for county coffers. Expanding markets for family farmers. Purchasing power for hometown businesses. And efficient "hi-tech" production for consumers. The facts of the industry, however, show that the Big Boys actually disable community development with self-serving contracts and tax breaks, market-monopolizing strategy and few local purchases.

Corporate livestock factories tout themselves as messiahs to the rural communities they target. They promise salvation for everyone: Job creation for local citizens. Increasing tax revenues for county coffers. Expanding markets for family farmers. Purchasing power for hometown businesses. And efficient "hi-tech" production for consumers. The facts of the industry, however, show that the Big Boys actually disable community development with self-serving contracts and tax breaks, market-monopolizing strategy and few local purchases.

Low wages and toxic conditions of the "new" jobs in confinement operations give the industry an incredibly high turnover rate. To keep the pork rolling, the companies bring in legions of people, often undocumented immigrants, whose desperate situations often only get worse. Says Terry Spence of Lincoln Township, Missouri: "These jobs are not paying enough money for one or two persons, let alone to support a family." Putnam, Sullivan and Mercer counties, home to PSF, have experienced a 20 percent increase in food stamp recipients since 1991 despite new employment.

While this influx of people might look good for retail sales, it actually adds up to a net loss for retailers, bankers, real estate and the local taxbase.

Because the market control of mega-producers displaces independent producers, the local economy winds up with one-third as many people involved in livestock production. While creating nine jobs for every 12,000 hogs produced, factory farms displace 28 jobs, according to a 1994 University of Missouri study by economist John Ikerd.

Concentrated corporate producers further deplete the local economy of local dollars by buying most of their supplies out of town. This is in marked contrast to family farmers who have always been the economic motor of rural communities. By purchasing from the feed and seed stores, farm machinery dealers and hardware outlets, a family farmer's dollar gets recirculated again and again. A Minnesota study, for example, found that operations with less than $400,000 a year in gross sales made 79 percent of their business expenditures within 20 miles of their farms. Larger operations made just half of their purchases within 20 miles.

Fewer jobs, less local spending and the flow of profits to distant cities means corporate producers actually drain the local economy. The overall effect can be seen in a Virginia study that compared the addition of 5,000 sows to the local economy by independent producers versus corporate producers. The independent producers' investment created:

- 10 percent more permanent jobs

- a 20 percent larger increase in retail sales

- a 37 percent larger increase in local per capita income.

Cornering the market

Some say this economic calamity is the price we must pay for cheap, plentiful food. Corporations claim they attain economies of scale, or a lower cost per unit by spreading fixed costs and overhead over massive numbers of animals. But industrialization is not a more efficient way to produce food. Studies show smaller independents are much better at managing costs and making profits. Iowa hog operations with an output of 1,260 pigs per year averaged 5 percent less in total costs per hundred pounds of pork than did large, specialized operations in North Carolina with an output of 5,000 pigs per year. Source: Hogs Today magazine.

Between 1989 and 1993, the most profitable large sow herds in Iowa generated a profit of $12.32 per hundred pounds of pork produced. The most profitable small herds in Iowa earned $12.93 per hundred pounds in the same time period. Source: Iowa State University.

A Kansas State University study found: The most efficient farm had only approximately 75 sows. The most efficient farmer, however, cannot make a profit without access to markets. Says Ron Perry, an independent hog farmer from Chillicothe, Missouri: "It used to be that within 10 miles, you could go to five or six places every week to sell your hogs. Now, you have to take them 50 miles to one place, one day of the month and take whatever the one corporate buyer will give you."

Because the corporation normally either owns the only packing plants around or has staked out most of the available processing capacity with exclusive contracts, they don't make much room or pay well for independents' loads. A 1993 report in Hogs Today, for example, showed that corporate producers in North Carolina were being paid $51 per hundred pounds of hogs sold directly to the processing plant compared to $39 per hundred pounds that independents received on the disappearing "open" market.

The truth is, factory farms have their run of the market because they own it, not because they're better farmers. When corporate-owned packing plants don't allow open access or competitive prices to family farmers, rural areas find their economic lifeblood slows to a trickle. Even though the CAFOs employ hundreds, the local economy winds up with a huge deficit.

Contract serfdom

If independent farmers become contract growers, they get hooked into the company's self-serving arrangements. They now need capital-intensive confinement buildings, equipment and lagoons. Rather than using resource-efficient farming methods like intensive grazing and crop rotations, they give up their independence and their communities to the corporation.

Grower contracts, as pioneered by Tyson, are essentially non-negotiable. They are take-it or leave-it deals that tie people and their homes into the corporate plan. Some like to call it a franchise system, but it has all the characteristics of a feudal system:

Contract farmers typically borrow at least $150,000 (to as much as $750,000) for initial confinement buildings and equipment. While that mortgage hangs over their family's heads, they will take home about $8 an hour after paying corporate-determined expenses, according to Neil Hamilton, author of A Farmer's Legal Guide to Production Contracts.

Many contract farmers are attracted by the promise that they will own the facilities one day. The problem is that the buildings last at most 15 years and the equipment half as long, according to research by North Carolina State University agricultural economist Kelly Zering.

What do the farmers own? Only a mountain of debt and the environmental liability of huge waste lagoons.

The corporation supplies the chickens or hogs, the medication, the feed and the only market. Growers have no say over the quality of supplies they receive or the schedules they follow. They usually have no recourse when headquarters underweighs feed or hogs. Growers have won large judgments for shortchanging practices, such as $2.9 million in 1996 in a case against Cargill. But with homes and families on the line, most just put up with it and cash their paychecks. Contract farmers thus become only glorified animal factory janitors.

What economists can't measure

High opportunity costs also hobble those communities that don't succeed in keeping out corporate factories.

Once CAFOs start spreading their manure in an area, people who might have bought a home locally or built a business will take their money elsewhere. John Neer, a banker in Macon, Mo., says lenders need to be aware that when corporations or contractors fail, they can't pay mortgages and equipment loans. And when only CAFOs are present in an area, rather than a diverse range of farms, businesses and families, the lender is likely to lose out on new, more stable loans and deposits.

The final result of crowding out family farmers and their community investments is something no economist or statistician can measure. When communities lose their family farming base, they lose parents' involvement in schools, and citizen involvement in church, in civic organizations and in independent-thinking government.

Perhaps the biggest peril is that rural communities are being deskilled and underemployed. These communities are filled with people who have hands-on skills and practical knowledge which have been passed from generation to generation. When those people are reduced to hosing out buildings and setting timers for feeders, these skills get lost. In the long run, a community is robbed of its sustainability. Thus, the difference between family and corporate farming comes down to that between self-reliant, vibrant communities or company towns.

Published in In Motion Magazine April 12, 1999.

![]()

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the

E-mail, Opinions & Discussion column click here to send e-mail to publish@inmotionmagazine.com.

Hot Topics || Region || Affirmative Action || What is New? || Education Rights ||

Art Changes || Rural.America || Essays from Ireland || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || En español ||

Healthcare || Global Eyes || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion

In Motion Magazine Staff || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Unity Book of Photos ||

NPC Productions || Links Around The World