|

" ... these were two men with convictions, compassion,

great dignity, and they were visionaries,"

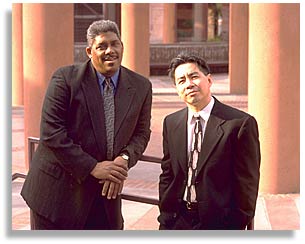

An interview with composers

Jon Jang and James Newton Part 1 - On the creation of "When Sorrow Turns to Joy" Interview by Nic Paget-ClarkeLos Angeles, California |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This interview of James Newton and Jon Jang was conducted for In Motion Magazine by Nic Paget-Clarke in Los Angeles, January 21, 2000. At the time of the interview, Jon Jang and James Newton were in the process of composing "When Sorrow Turns to Joy - Songlines: The Spiritual Tributary of Paul Robeson and Mei Lanfang" (libretto by Genny Lim). This piece is inspired by the artistic and political legacies of the African American singer/actor/humanitarian Paul Robeson and Chinese operatic star Mei Lanfang. It was commissioned by Cal Performances - University of California at Berkeley and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. In Motion Magazine: In 1994 you were both doing residency work in Soweto. During that time you identified conceptual ideas for When Sorrow Turns to Joy. That must have been very exciting, where you were, what was going on that time, and then this idea. Can you describe the atmosphere and environment of those residencies and why you think it was there and then that this came to be? James Newton: Jon and I went to South Africa, four and a half months after Mandela became president. I was the first person in my family that had the gift of placing their feet on African soil again. It was an amazingly significant event, not only for me but for people in my family. When I got back home they wanted to hear about it and see the pictures and so many things were discussed. It was also significant that I went with Jon because we had been working together for a number of years and we had done a number of benefits, anti-apartheid benefits, benefits for unions.It seems like the beginning of our association started with political causes. We had a commonness in the music that influenced us. That music was Ellington, Mahalia Jackson, Olivier Messiaen, Eric Dolphy, Thelonius Monk. When we went to South Africa, two of the things that really struck me were the feeling of optimism that existed now that people for the first time in their lives had the opportunity to vote; and secondly the dedication of the people in the ANC was just so moving I can’t even put it in words. Everyone would say “welcome home.” It felt like home. It was the first time in my life, other than in the Black church and in some of my experiences in the South, that I did not feel out of place in a society. I felt more at home there than I did here in a lot of ways because being a person who travels you become so acutely aware of the effects of racism. When you are stepping in and out of so many societies you become attuned to a lot of nuances in the dynamics of human interaction. A lot of things happened, but one of the many things that I remember about being in Soweto and participating in workshops with the young adults was how they would gravitate around Jon when he was playing piano, and myself when I was playing flute and working with the musicians. I remember how we heard a lot of African American influences.I think this project really clicked when we visited the South African Chinese community. I think I can speak for Jon in this instance, he felt very at home in the South African black community and I felt very at home in the South African Chinese community. We had always been dealing with these cultural pluralities in a way that is not appropriation but looking deeply inside a culture and looking for the nuances. We noticed that as Jon studied Chinese music more and more, and particularly the sorrow songs, there were parallels. The Chinese musicians that we played with would play Duke Ellington’s “Come Sunday”, and they said that they could relate it to sorrow songs and folk songs that existed in their literature. In addition, when I heard some of the pieces that we played there they reminded me of spirituals. We started to see all of these parallels. Jon Jang: For me the time that I spent in South Africa and the month I spent in China was about searching for my roots. As a Chinese American, growing up in white middle class Palo Alto, I did not really feel connected to my grandparents, who spoke Cantonese, or even the Chinese workers who built the railroads. For James it was discovering Africa, for me in China it was problematic because I don’t speak Chinese. It was a more difficult process ... it had a different impact for me than it did for James. I don’t intend to artificially create my life like “Yes, I came out of such and such an experience ...”. My particular experience as a Chinese American is that during the 1970s, I was exposed to an explosion of music, John Coltrane, the Black Liberation movement, and the Asian American movement - that’s my experience.But back to your question, this work grew out of James’ and my collaboration together throughout the years, We had been performing in each other’s ensembles, writing works and supporting each other. This is culminating in “When Sorrow Turns to Joy”.When we performed at UC Berkeley at Cal Performances in February, 1993 to help celebrate African American history month and Chinese New Years the immediate historical person that came to mind was Paul Robeson but for Chinese New Year there wasn’t any Chinese artist or leader in the United States that I could identify with.I go back to a story. When Stevie Wonder in a song praised Martin Luther King Jr., and he praised Abraham Lincoln, and he praised Cesar Chavez, the main Asian person he praised was S.I. Hayakawa. Hayakawa was not an Asian, or Asian American, or Asian Canadian, he was not a person, period, that I would embrace. And that got me to thinking about who are our heroes.Later, I needed to do some research on Mei Lanfang and Beijing Opera in China when I was composing the score for the dramatic adaptation of Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior. While I was there I discovered a photo of Paul Robeson with Mei Lanfang. I discovered Mei Lanfang.So, there was our conversation after the February concert I mentioned before, there was my experience in China, and then the meeting with James in South Africa. There was a convergence of what this idea of the project meant in our lives, in our music. In Motion Magazine: You were also both in China, Why is Beijing opera key to the process of the creation of this piece about Mei Lanfang and Paul Robeson? What else did you learn about Mei Lanfang while you were in China? James Newton: One of the things that you have to consider is Mei Lanfang was very much a multicultural artist. For example, he took aspects of bel canto, Italian bel canto singing, and used that with the traditional singing of Beijing Opera to bring forth all of these innovations.He innovated the role of the dan, which is the female role, and he was a master at playing that role, a male voice sung in falsetto. We also understand the fact that he was a very political human being. When the Japanese occupied China he grew a mustache so he couldn’t play the female role. Jon Jang: That was during the War of Resistance against Japan from 1937 to 1945. It was the prime of his life. He was born in 1894. He stopped performing and did Chinese brush painting. Similarly, Paul Robeson was persecuted during the McCarthy period which was the prime of his life - 1950 to 1958. There were parallels in the stands they took.In addition, while Mei Lanfang studied Italian bel canto to develop his vocal techniques, he also studied African vocal techniques and visited Egypt.

Jon Jang: They met in London. When they met in 1935, both Paul Robeson and Mei Lanfang had recently performed in the Soviet Union, Paul Robeson in ’34 and Mei Lanfang in ’35. They were invited by Sergei Eisenstein and other artists and intellectuals in the Soviet Union. Mei Lanfang was trying to perform in London but they didn’t respect him there. He even offered a huge reduction in fees to make it happen but it didn’t. Fortunately he met Paul Robeson and they exchanged their views on culture. James Newton: There was an incredible photo of Mei Lanfang in his costume for playing the dan role and underneath that photo were four words, “The Embodiment of Beauty”. And that phrase hit both Jon and I like a ton of bricks. It’s very significant. His voice was beautiful, the costumes that he wore were beautiful. They say his movement was elegant and beautiful and refined. In Beijing, we visited his house and saw the courtyard were he would practice his movements. Jon Jang: Mei Lanfang is not his real name - we don’t know what his real name is, but Mei Lanfang is roughly translated as fragrant orchid. James Newton: And you look at his paintings - he was an amazing painter.One of the things that I have tried to do, because it would take both of us the rest of our lives to study Beijing opera, is to learn to open up and allow certain things to make an imprint, spiritually. In that way they get transferred into music. I’m not going to say it’s serendipitous what you end up choosing, but what you grab relates to who you are as a person. This is then transferred into language. And one of the things I listened to was Mei Lanfang’s phrasing. And the nuances, the ornaments that he would put on his voice. The way he would use glissandi.We are not actually dealing with the art forms but these two humanitarians who are very close to their people, whether it’s the Chinese people or the African American people. They were really international citizens. They could both see the universality. Jon Jang: I can give a story about Mei Lanfang. Look at the concept of reconciliation. In the 1950s when there was anti-Japanese sentiments by Chinese people, for good reason, and despite what the Japanese military and government did to the Chinese people -- Mei Lanfang performed a benefit for the Japanese people who were victims of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings.

James Newton: Robeson had a strong connection to spirituals. And even though he sang folk pieces from all over the world and he sang in all these different languages, twenty-six languages, one of the things he was most known for was his interpretation of spirituals.Along with Roland Hayes and Marian Anderson and a number of other artists, he wanted to give a dignity to the spiritual in the sense it is so significant to the fiber and core of the African American. It’s a crucial part of not only our history but our life -- it’s like a reflection of the spiritual core of a people. He conveyed that powerfully with his voice.In the music that we’ve done to this point there is a piece that Jon and I co-wrote, we actually wrote part of it in China, and other parts in Minneapolis -- it sounds like a spiritual. But it’s got a couple of twists in it that reflect our experience in China. They fit together beautifully.Then there’s the fact that Paul’s voice had a great degree of flexibility. It’s why he could sing Chi Lai, the Chinese national anthem. It’s one of the things that really gravitated Jon towards Paul. Jon Jang: The first Chinese music I heard was when Paul Robeson sang Chinese folk songs of resistance in Mandarin, when I was four years old. He made a recording in 1941 in New York with a Chinese choir. He was 43 years old. This was after he returned from London. You see he was studying African and Chinese languages at the School of Oriental and African Languages in London. I visited the school. As Harry Belafonte said, he wasn’t a person that was trying to sing the songs like a person being a person from another land singing it -- he wanted to actually be that person. James Newton: Mei Lanfang and Paul Robeson were breaking down stereotypical images of what Western society deems to be safe ground for people of color artists. We’re still fighting those stereotypical images. Our art is a lot more flexible than society will allow us to function. It can move in a lot of different areas. In “When Sorrow Turns To Joy”, the powerful words that we are setting by Genny Lim lead us in many ways, and we feel free to go wherever the text leads us because Paul was flexible, Mei Lanfang was flexible.The point to me is if people leave the hall, they are moved, and they have the feeling that these were two men with convictions, compassion, great dignity, and they were visionaries, if we can give them that picture, we can also show them that members of Beijing opera, and Chinese Americans, and African Americans can find a new kind of art. This piece is different than anything out there, it doesn’t sound like anything else. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2020 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||