|

"Whether the program is political, which many are,

it's still rooted in a strong spiritual feeling." "Listen to your own voice!" filmmaker, Sandra Osawa by Victor Payan Edited and transcribed by Grace van Thillo Seattle, Washington & San Diego, California

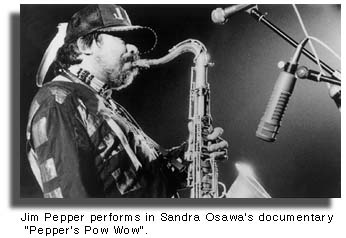

Victor Payan: How did you get interested in documentary filmmaking? Sandra Osawa: It was an evolving process. I've always been interested in communication aspects. I wrote poetry at a young age, continued in college and realized, "This could be taken seriously." I asked somebody, "How do you actually make a poem a poem?" Dealing with form, structure and how to break lines was a whole new process. It's interesting but once you learn that form, a lot of mystery is taken out. It evolved from that point to thinking, "If you want to communicate through film or video, how is that done ?" I worked for my own tribe as Community Action Director of the poverty program. There was never anything to do on the reservation. I tried to have a movie night, but it was difficult with no films about us and particularly nothing about Northwest tribes. That always stuck in my mind. Then in Los Angeles I heard UCLA was looking for minority people to go into film school. It was the early '70s during the push for more diversity, and there was money to do something about it. I jumped at the chance and dropped whatever it was I was doing, and headed for that program. I thought, "This is exactly what I want to do and find out about." A process began but I hate to say, I only stayed half a year and became a drop out. I tried getting more access to equipment thinking, "I have enough information now, and with equipment I can do this on my own." Victor Payan: So you didn't necessarily drop out, you kind of jumped ahead! Sandra Osawa: (Laughs) That's a good way to put it. It was jumping ahead, because times were such that you became very impatient having to wait. The opportunity was there and you could see the potential of what could be done. I mean I know society really demands that credential. It would have been nice to have the degree, but I was impatient at the process of sitting there talking about theory. I wanted to jump in and do something! Victor Payan: Right. One reason I think people go to film school is to access equipment. But you didn't get access to the equipment. Sandra Osawa: It was such a disappointment, and we all felt disgruntlement and discouragement. We tried putting pressure on to release equipment, but it wasn't possible for any of us. What was great about the program, however, was seeing its potential. We all completed our first projects and it was uplifting to see student films from diverse communities- from people of color! That kept us motivated and propelled many of us out into different directions. Moctezuma Esparza is one of the success stories of the program. "I decided to try the most difficult thing."

Sandra Osawa: It was a one minute project called, "Curios". I decided to try the most difficult thing, a short piece, and was really elated with it. We shot inside a museum at people coming through looking at Native American curios. Mummies were still being displayed. We shot that and edited the whole thing together. It showed how white people really see us, in terms of looking at us behind glass cases. It was transferred to video and shown recently at a film festival of retrospective works. It was fun to see again. Victor Payan: Yes, with it documented, it's amazing to see how this becomes a record of the time or way of seeing something. Sandra Osawa: Yes it really does. It would be great to see the other student projects, because it was a first expression and statement showing positive things institutions can do when their heart and attitude are in the right place. Unfortunately during the '80s, much of that heart and soul have been gutted. Victor Payan: Is it harder for people starting out now then it was in the early '70s? Sandra Osawa: I think it's probably equally as hard, because we did some steps backward through the '80s. It's about as hard today as it was when I first started. That's not a very positive statement, but it shows the struggle isn't necessarily a linear one, about climbing the ladder and the higher you go, the easier it gets. It's more a cycle kind of thing. There's always been difficulties for people of color being in the media, and I think the obstacles are very real. After that first thrust of affirmative action, doors opened a little easier, but now I don't feel that same political climate or energy. We have a little track record now, but basically we're starting over trying to prove our credibility . Victor Payan: Perhaps there's not as many "ins" for students today as in the early '70s, but do you feel access to equipment is easier now? Sandra Osawa: That's a really encouraging thing. Equipment is coming down in price and going up in quality. Film cameras used to be so expensive and everything was so removed, that financially, if you didn't have access in schools, it was almost impossible. Editing equipment is coming down in price also. So it's possible for individuals to do a long-range plan, get their camera and editing equipment and go forward with their project. Victor Payan: As your career developed, what were some obstacles you faced as a Native American filmmaker doing Native American work ? Sandra Osawa: In the mid-'70s we had to (and this sounds laughable now), but we had to bolster ourselves using cover letters from Native American men. There were only two Native American women doing the initial push toward NBC for the Native American series, and credibility was such that doors would open if a letter came from a Native American man. Even though we wrote the letter, we had it signed by a man in the community. We'd receive comments of how persuasive the letter was. . .and the Native American man took full credit saying, "Thank you". So we did a lot of game playing in terms of the sexism that existed, but we wanted so much to get a program launched. We were willing to do these things, and put our work out under somebody else's name! For initial contacts we made sure some Native American men were present to do the official talking. Victor Payan: Have things really changed since then? Sandra Osawa: Well, that's a good question. I know it's still there because if you look at the funding opportunities from my own community, male producers receive the larger share of funding. Those things weren't necessarily unique to the '70s, but we tried to figure out how to get around the obstacles and gain opportunities to write, produce and have a series. NBC had done public information series on Blacks, Asians, Chicanos, and their last was to be about Native Americans. It was low budget but it was an opportunity to be on the air. That series in '75 became the first to be produced, acted, written and researched by Native Americans in the country. It went to all O & O stations-"owned and operated." It was a major historical piece, and set a precedent that Native Americans could really produce. Victor Payan: Has that been done since? Was last year's big series originated by Native Americans. Sandra Osawa: You mean the Turner series. No, I don't think it's been done since, and that's another disturbing thing. You'd think since the mid-'70s we could build from there, but again, the ladder concept doesn't hold for us. Each decade you have to prove yourself again and again. I mean, how many ladders do you have to build? I think those major series by Turner and Costner, didn't have Native American involvement at the highest levels, especially the writing levels. They weren't very compelling, passionate or involving programs, and you sensed the absence of Native Americans. Now with "Eyes on the Prize", you definitely had a black producer paired with a white producer. Having a black producer at top levels made a difference in the passion they were able to deliver. Victor Payan: Right! One issue which seems very important to many Native American writers is the idea of how the story is told. Storytelling qualities are very particular within a particular tradition. Sandra Osawa: Yes, it's really about voice and expression, and making room for all voices. Especially in this country which is supposed to be devoted to diversity, hopefully we can listen to everyone. Besides, stories are more interesting when told by many voices, as opposed to being channeled through one culture or one point of view. I think that's the goal we have to set for ourselves. For example, in talking about the series' concept, the art director for NBC wanted the Native American host to appear in a breechcloth and feathers! Had a Native American producer not been there, the conclusion might have been, "Sure, fine! Let's do it!" The tendency would be to go along with someone at a higher level, which he was. Victor Payan: So it's at a pretty basic level. Sandra Osawa: Yes, really basic and from there you get into deeper levels of the script process, production ideas, stills and visuals. It's a tremendous night and day difference having somebody from inside the culture making important decisions. It contributes to whether you tell a story with heart and soul, or whether you're just in it for the job! Victor Payan: What reactions did you receive about the series from mainstream media and the Native American community? Sandra Osawa: What amazed me most was the avalanche pouring in from across the country's non-Indian community. I knew the native community would be happy with it, and they were. But the non-Indian community, teachers from all over the country said they woke up at 6 am. to see the series. They wrote and asked, "Why can't we have something of this quality at prime time?" Although it aired at an early time we still reached millions of people. I realized at that point, "It's not what they've been feeding us", the fact that there's no interest in Native American issues. Letters came pouring in, and it was an amazing experience to realize the power of the media to reach out and communicate solid ideas to the rest of America. Victor Payan: Was it discouraging at times to feel you were the only one out there? Sandra Osawa: Discouragement comes with the territory, whether it's the '70s or late '90s. When I began I didn't know any Native American women producing, and had nobody to identify with or look up to. I think we all make a contribution being just where we are. There are ripple effects with people saying, "Oh, yea! I can do that too!" But it's tough for minorities! You face continual rejection no matter how many projects you've done and how good your ideas are. It's relatively new territory for us. We haven't been in the field that many decades, so facing and overcoming obstacles makes the way smoother for others. Victor Payan: In starting your career who or what influenced you, filmmakers, films or things you read? What helped develop your style? Sandra Osawa: I was influenced by the poetry of writers with spare and clear imagery. I wanted to find images that were somewhat, I want to say simple, but simple could be misunderstood. In terms of being like poetry, the more you refine it, the less words you have to use. I'm driven by poetry with strong, specific imagery. That really reaches people. It's a discipline that guides me to reduce and clear out the clutter. It's hard in documentaries because they are driven by words. So we try finding ways to make words come out as strong as they possibly can. Victor Payan: I think you are very conscious of the imagery used to tell the story on screen. Sandra Osawa: Right, it's fun because you don't just have to use words. You can find a different way to say things with images. The real challenge is experimenting to see if things can be said more clearly. Victor Payan: Now tell me about the Jim Pepper piece. I saw it and really liked it. How did you get interested in that story? Sandra Osawa: Since the early eighties I'd wanted to do something with Native American music. I came across Jim Pepper, whose parents are Kaw and Creek and did initial shooting when he appeared at the National Congress of American Indians Convention in 1984. I was taken aback by what he did with the music, because I'd never heard a Native American jazz musician. We had done our share of listening to jazz, and I thought," Wow, how come I didn't know Jim Pepper existed? And if I didn't know he existed, not many people must know about him." We did an interview in 1984, and tried unsuccessfully to get funding. Then around 1989 I decided to start up without funding. We got Jim's transportation paid to Tuba City with an Arizona Arts Commission grant which also paid a musical fee because he was to teach a class at the high school. When Jim visited his parents in Portland, we shot an interview with him and laid that down. The shooting in '89 became the bulk of our work, because we ran out of time. Jim died in '92. After he died I became very angry and frustrated thinking, "This is a prime example that we can't get our stories funded because nobody knows, first of all, the people who are important to our communities." So when they (the funders) sit on panels asking, "Who's Jim Pepper? I don't know! So let's not fund them!" It becomes a Catch 22. How do you get a project funded that's important to one community, but other people have no knowledge of it? Without a clearly written proposal about the importance of this project, his story like millions of others, would never be told. After that second proposal attempt, we finally received an ITVS Grant. It was a relief getting one important story out, because it deserves telling. In the story, we didn't want to use a narrator and rely on a distant voice coming from outside. That made the piece much more intimate. Victor Payan: Yes, you really connect with him, through his words and those of his friends. After you got the film made, the next step was to get it seen. Sandra Osawa: Right! We have it before POV. They probably have 500 submissions and can only choose 10! So it's ultra competitive. There just aren't many slots open for independent producers. Also we'll try PBS. If it becomes a "soft seed", it's at the discretion of local stations to pick up a program or not. There are many conservative PBS stations across the country, and in terms of politics, they aren't always atuned to diversity programs with minority producers. That's a big obstacle we face today. Other avenues for Native American filmmakers Victor Payan: What other avenues are open for Native American filmmakers? Sandra Osawa: Cable is a place to go knock on the door, and the educational market is also receptive to good materials for libraries and colleges. It takes money for marketing outreach, but our limited marketing attempts have been well received. By accessing addresses and telephone numbers, we've found many Indian related schools and colleges teaching Native American subjects who are looking for good materials. The MacArthur Foundation also did a special mailing of Native American programs sending it free to all libraries. That made significant in-roads, and these kinds of attempts are great for independent producers. Victor Payan: In putting together a documentary, is it difficult to access historical materials? Is it different looking through the National Archives, Library of Congress or tribal archives? Sandra Osawa: The whole archival question is difficult because we've found most museums are not properly labelled. Even in national or state museums, you'll see something like, "Indian by canoe". This is of no use if you're looking for a Yakima person named Jack Jones. The whole labelling and identification process tends to be very impersonal. Many times we don't have names or dates attached to photographs. We've found the best source is living people who help us find a particular photograph. It takes longer that way, but it's given us many rich pictures. In the piece we're working on now called, "Usual and Accustomed Places", we're looking back 150 years through the eyes of individual Indian people who fought for treaty rights to fish. It demands heavy use of archival photographs and is a painstaking process, but it will be interesting once we're done. There were six sites in Washington state where we signed major treaties. We thought the locations would be marked and identified, but most were not. More importantly, we thought there'd be portraits of the Indian people who signed treaties, especially in tribal museums. We've found an enormous lack of personal identification about our history. It's an example that our history has not been documented. We always knew it hadn't, but we didn't realize the gap was so huge. Victor Payan: Unless somebody with the knowledge is there to see what's missing, nobody will catch it! The recent documentary series about the West talked about Native Americans through generic photographs. Sandra Osawa: It was frustrating for me to look at because the series actually used wrong photographs, even different tribes. I thought, "Wow! They had money for accurate research." One of the wrongs done in history is we've become so abstract. We have not been personalized. It's difficult for anyone to get a handle on who we are as a people. Series like "The West" perpetuate us in the abstract and that's very damaging. It's also frustrating for many independent Native American directors and producers to view, because we're doing primary research without the funding. It's appalling to see heavily funded series which lack the research. How can this crime go on? Victor Payan: Right, and the "The West" was considered more sympathetic than others out there. Sandra Osawa: It might be considered sympathetic except for the fact that it simply rehashes stories like Chief Joseph and others whom we've already heard about. It keeps instilling in the minds of America, "We are the losers, and we are abstract people, rather than particular people with particular lives!" Victor Payan: So that further emphasizes the importance of having an authentic voice telling the story. Sandra Osawa: Yes, but authentic voices need funding. It's expensive to compete in the world with inadequate funding. Look who gets funded to tell an Indian story. Is it the Indian? No, it's not! It's the non-Indian. That inequity continues to exist, and we have to ask ourselves, "Why? What is everyone so afraid of? Why can't Native Americans be afforded the same opportunities to tell our stories? Why does it have to be told through a non-Indian voice?" Victor Payan: Doing the math from your series in '75 to 20 years later now, there hasn't been one with authentic Native American voices. Sandra Osawa: Yea, it's amazing! Totally amazing! Victor Payan: Knowing these obstacles, what advice do you give students interested to get into the field? Sandra Osawa: Do the work! That's the best thing. Have a five or ten minute sample showing what you can do. I'd be impressed if someone came to me with a good ten minute sample. Whatever skill you bring in, whether it's your camera work, sound, or writing. It comes across in five or ten minutes. It's a good idea to invest in a good sample. There are also people who can write good funding proposals. That's really an art and one of the most important things. People not interested in technical aspects can also be involved, and students can find independent producers who always need help. Volunteering on someone's project gives you invaluable experience. If you're relegated to logging tapes, which might seem tedious and menial, you're closest to the material and if you can talk about it intelligently, that's invaluable. You can prove yourself in almost any capacity. Victor Payan: What has been the most rewarding moment in your career? Sandra Osawa: There have been a couple rewarding moments, and both had to do with actual air time. One was receiving the award from NBC for the Native American series. That was important because it was such a first. It represented hope and the feeling, "We did it!" There were skillful Native Americans at all production levels. We produced a program every two weeks, and someone later said, "Oh that was a suicide mission! You were supposed to fail!" I know we were supposed to fail, but I stayed up around the clock, many many days. We shot our own film, brought in our own stills and also the music. The program was supposed to be like a talk show, but we made it a real series with production value. The reaction from inside NBC was shock. They had no experience working alongside Native American people, and they didn't know Indians could act, produce or do anything. "Wow! They're doing this!" People were very impressed with the whole series, and although it was our first project, it confirmed the idea that we can do it if we're given an opportunity. The second rewarding moment was the recent airing of "Lighting the Seventh Fire." Once again, it was the first Native American program shown on POV. We had a good feeling that another goal had been accomplished. You hope that more doors will open, but you can't think about that when you're concentrating on the work. Doing the work and having it seen is the goal. Victor Payan: What guidelines do you follow in telling a story? Is it instinct, or is it a conscious effort to tell the story in a certain way? Sandra Osawa: Many of the stories have a cyclical feeling to them. That's both conscious and unconscious. The program is a reflection of my attitude, values and way of looking at things in terms of a circle. "Big Mountain", for example, begins with rock art and ends with rock art. There's a front and back cover. "Lighting the Seventh Fire" begins with Eugene Begay, a spiritual man, and it also ends with him. There's also a strong element of spirituality in all projects I do. Someone once said about Jim Pepper, "He was a very spiritual person, but he never talked about it." That's how we approach our videos. They are very spiritual in their basic construction and in their basic message. I don't talk about it often, even in the video itself. Whether the program is political, which many are, it's still rooted in a strong spiritual feeling. That's probably a departure from how a non-native would produce the same subject area. I doubt it would have that element of spirituality. That's what sets my work apart, and hopefully makes it stronger. Victor Payan: Do you have some final advice for students interested in pursuing this career and telling their stories? Sandra Osawa: You have to be tough, persistent and willing to listen to your own voice, even if everyone around you gives you rejection. Keep focused on your own vision, no matter what, and I think you'll be successful. That may sound optimistic, but you can't be too influenced by either praise or negative aspects. Victor Payan: Finally, what's kept you going when you've faced discouragement? Sandra Osawa: Well, I think what keeps us going, is we MUST keep going! There's a feeling that we must survive! Victor Payan is an award-wining writer and humorist whose work has appeared in El Sol de San Diego, the San Diego Union Tribune and Pocho Magazine. He recently served as associate producer for the upcoming PBS series The US-Mexican War: 1846-1848. You can usually reach him at consesos@aol.com To inquire about obtaining videos by Sandra Osawa:

Also see:

|

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2020 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |

Victor Payan: What was your first film?

Victor Payan: What was your first film?