|

|

|

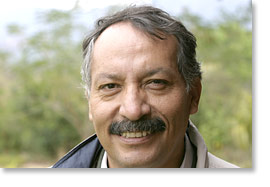

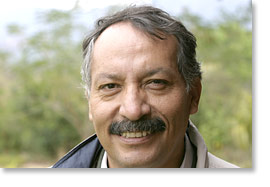

Miguel Angel Crespo at the Center for the Investigation and Production of Bioregulators in San Luis, Santa Cruz, Bolivia. All photos by Nic Paget-Clarke.

|

|

|

|

In San Luis, Santa Cruz.

|

|

|

|

PROBIOMA coordinator Rosa Virginia Suarez.

|

|

|

|

Meeting rooms and dormitories at the Center for the Investigation and Production of Bioregulators in San Luis.

|

|

|

|

Guido Zarate studies insects at the Center for the Investigation and Production of Bioregulators.

|

|

|

|

Test crops.

|

|

|

|

Edson Meneses, agronomist engineer with a speciality in the pathology of insects. The San Luis laboratory.

|

|

|

|

The vinchuca (Triatoma Infestans), the vector for Chagas disease.

|

|

|

|

Mónica Meléndez, an agronomist engineer in charge of production in the PROBIOMA laboratory.

|

|

|

|

Mark Camburn, economist and interpreter /translator at PROBIOMA.

|

|

More photos. |

Miguel Angel Crespo is the director of PROBIOMA -- Productividad Biosfera Medio Ambiente. PROBIOMA is a private institution. Its mission is to “contribute to the investigation of and technological innovation within biodiversity; as well as to promote the local administration, sovereignty, and sustainability of natural resources to improve the living conditions of the people”. PROBIOMA was co-founded in 1990 by Miguel Angel Crespo and Rosa Virginia Suarez.

This interview was conducted (and later edited) by Nic Paget-Clarke for In Motion Magazine on August 28 and 29, 2006 in PROBIOMA’s offices in Santa Cruz and in (and traveling to and from) their Center for the Investigation and Production of Bioregulators in San Luis, Santa Cruz department, Bolivia. The interview was interpreted between Spanish and English by Mark Camburn. To see the Spanish version: click here.

Food sovereignty and local control

In Motion Magazine: When and why was PROBIOMA founded?

Miguel Angel Crespo: PROBIOMA was founded the 20th of May, 1990. It was founded by a group of professionals very worried about the sustainable management of natural resources in Bolivia. Taking into account that Bolivia is one of the ten richest countries in mega-biodiversity in the world, we thought it was very contradictory that Bolivia being such a rich country was in fact one of the poorest countries worldwide.

In that context, we put together a certain number of challenges, tasks, so that we could, using microorganisms, take advantage of the grand richness in biodiversity to contribute not only to food sovereignty but also to ensuring that natural resources in this country are managed, controlled by local rural people.

PROBIOMA is neither a conservationist NGO (non-governmental organization) nor an institution that works solely in development. It combines aspects of conservation with sustainable development. PROBIOMA works on fives axes.

The first is the transference of biotechnology, as a contribution to agroecology. The second is biodiversity, the local control of protected areas through community eco-tourism, as a contribution towards the conservation of natural resources. The third is communication, a public information service. The fourth is a new focus, the creation of INBIOTEC, the Institute of Biotechnology and Biodiversity, to train people within Bolivia. And the fifth is a program of political incidence. This has developed within local organizations to put political pressure onto the government so that they have representation on the use and conservation of biodiversity, the implementation of agroecology, food security, etc.

The Green Revolution in Bolivia:

from haciendas to agribusiness

In Motion Magazine: Could you talk a little bit about the history of the Green Revolution in Bolivia?

Miguel Angel Crespo: The Green Revolution started in 1956. Until that date, or at least until 1952, Bolivia operated under a system of haciendas, slavery basically. With the Bolivian revolution in 1952, haciendas that were situated within the area of the valleys and the Altiplano passed into the hands of the indigenous peoples and the campesinos under the agrarian reform law. Then, in 1956, there was a plan promoted by a (North) American expert (Merwin L.) Bohan. Called Plan Bohan, this proposal called for a march towards the Bolivian eastern lowlands to establish an Import Substitution policy; that is to say, taking advantage of the lands of the Bolivian Oriente for the exploitation and production of sugar cane, fundamentally, and cotton.

This policy began the process of the Green Revolution because it brought about were the first industrial bases in the Oriente, establishing a basis for an extensive agriculture, the development of an agro-industry. This would later have great influence on peasant agriculture in the valleys and on the Altiplano. This agro-industry promoted the import of agro-chemicals, which later were also used on the small-scale farms that had been granted, distributed during the agrarian reform process.

I would say that since the Green Revolution began in the ’60s up until now, this has become a major problem for Bolivia. We now use more than 200 types of agrochemicals, as much in peasant farming as agro-industry, including on crops for export such as soy, sunflowers, and sorghum. Of these 200 agrochemicals that have become commercialized in Bolivia, 80% have the same active ingredient. They change the names but they are selling basically the same product. This has fundamentally influenced agricultural production in the valleys and on the Altiplano, and has changed traditional methods of using the soil, such as crop rotation.

Imported chemicals, exterior markets

Also, this has contributed to the emergence of local and export markets demanding a more intense use of our natural resources with serious social and environmental impacts. A clear example is the more than half a million hectares of degraded soil in Bolivia, of which 300,000 are right here in Santa Cruz. We are talking about a high impact on human health, the fact that cancer has become one of the five most common illnesses in Bolivia. And we are also talking about the high levels of corruption that are found among the authorities who deal with the importation of chemical products, the circulation of over $100 million dollars per year. Many of these products that are imported are registered without any environmental impact studies or neurological studies being carried out; and many of them are illegal in other countries.

There have even been impacts on social health, for example the control of Chagas disease. Bolivia is one of the countries with the highest levels of Chagas disease in the world. Fifty percent of the population has Chagas disease and fifty percent are at risk of obtaining Chagas disease. For many years, different governments used chemicals to control the Chagas vector, (a vector is an organism that does not cause disease itself but which spreads infection by conveying pathogens from one host to another ) which is the vinchuca, with the scientific name of Triatoma Infestans. They used DDT to fumigate vinchuca. Now, they are using a highly toxic product called Delta Matrina, which is illegal in other countries but has been authorized for use in Bolivia to control this insect. Gradually the vinchuca has developed resistance to the agro-chemicals.

So, the Green Revolution has even had an impact on the public health sector. In this case, the Bolivia state promotes the import and sale of agro-chemicals under the pretext of eradicating the vector of a disease.

Agro-chemicals or agroecology

The Green Revolution also has had an impact on the formation and training of academics. Universities, both state-owned and private, put a lot of emphasis on what are the “benefits” of the Green Revolution. Therefore they don’t put any emphasis on agroecology, which should be the basis for rural sustainable development policy.

This means that the professionals at the universities have a very good understanding of the chemicals and how to use chemicals in agriculture for this or that crop. They have a development focus on extraction rather than sustainably taking advantage of natural resources. In other words agronomist professionals are pharmacists. They just sell the medicine that the crop might need. They don’t make an integrated diagnosis of the problem. They don’t give any advice on how to prevent pests, diseases in crops. There’s no integrated focus on the reality of the situation.

In conclusion, we can say that the Bolivian state has not concerned itself with the sustainable management and sovereignty of natural resources, of biodiversity.

In Motion Magazine: Is the Green Revolution still going on?

Miguel Angel Crespo: I would say yes because agro-industry still has a lot of influence with the agro-chemical companies, and also the companies that promote genetically-modified seeds, particularly soya.

But, there is now a greater understanding of what the contribution of agro-ecology is. Despite all this, there are important advances in the Altiplano, in the valleys, in the lowlands; of experiences with agriculture that are very interesting, resulting in the fact that the current government has established new agrarian policies of ecological agriculture, based in agroecology. They have promulgated Law 3525. This law is the result of contributions made by institutions such as PROBIOMA and the University in Cochabamba, AGRUCO, and other organizations of ecological producers.

This reflects the value that agroecology has in this country, and many companies are trying to take advantage of these advances to make themselves more competitive in the international market. There are the cases of the export of ecological coffee, cocoa beans, quinua, sesame, and wines based on ecological grapes in Tarija; experiences with soy; and also with some fruits such as strawberries.

In Motion Magazine: What are some of the corporations which promote the Green Revolution?

Miguel Angel Crespo: There are several companies here and also associations of farmers controlled by the big companies, for example: ANAPO, the National Association of Oilseed Producers, Fundacruz, and the Regional Seed Office; etc.

In Motion Magazine: What are some actual companies?

Miguel Angel Crespo: Local companies import products and work for transnational companies like Monsanto, BASF, InterAgro, Mainter, and Dow Agro, a subsidiary of Syngenta.

Agro-ecology and ecological equilibrium

In Motion Magazine: How do you define agro-ecology?

Miguel Angel Crespo: It’s very hard to define in a few words, but from my point of view it is a combination of several different strategies. It is based on traditional knowledge, native genetic resources, native seeds, traditional practices for the control and prevention of pests and disease in crops; the use of biological diversity; and respect for cultural identity. It is a very much related to the security and sovereignty of food.

In Motion Magazine: How do you combine traditional knowledge and scientific knowledge in your own experience with PROBIOMA?

Miguel Angel Crespo: In the year 1992, PROBIOMA carried out a diagnostic of the relationship between indigenous communities and their use of natural resources. In this investigation, we proved that there was a very deep relationship with the use of the genetic resources of biodiversity, the knowledge of the use of soils; a knowledge of the climatic aspects and their influence on the physiology of the plants; a knowledge of what is the fauna and flora of an area.

This led us to further investigations in protected areas in which we saw the relationship between the indigenous communities and biodiversity’s resources. This led us to the suggestion that the administration or the management of natural resources should be in the hands of the local communities.

And, at the same time, we did more precise investigations. For example, in the area of microbiology we discovered a whole world of beneficial microorganisms. This basis of being able to formulate and transfer biological controllers and, with the help of technology, helped us give back products to the farmers which allow them to substitute for the use of chemicals and also, at the same time, implement a basis for sustainable agroecology.

In Motion Magazine: What is ecological equilibrium?

Miguel Angel Crespo: From my point of view, ecological equilibrium is when there exists a natural control within an identified area such that different species live together in equilibrium without the possibility that one of these species can dominate over another one. From our point of view, when man can live in harmony with nature.

Farmer involvement / women’s groups

In Motion Magazine: How do farmers become involved in the work?

Miguel Angel Crespo: When we started the first tests with microorganisms for biological control, we did it with women’s groups. They were the ones who were most worried about the impact of agro-chemicals on the health of their husbands, of their children. It was they who showed most interest in how this new technology could help substitute for chemicals, to help establish a more sustainable agriculture, and contribute to the health of their family. They saw less the commercial aspect and more the family health aspect. That was the first step and we validated the technology with these groups.

The second step was to show farmers that they could substitute this sort of technology for chemicals with the same efficiency and have a similar set of economic results. We would tell the farmers that they weren’t going to produce organic vegetables to achieve better prices in the market but that little by little they could substitute biological products for certain chemical products which were harming them.

In Motion Magazine: On a daily basis, when you are developing a new product, how do the farmers and the scientists work together?

Miguel Angel Crespo: That is through the technical team that we have which works on the transference of the technology in the countryside.

In Motion Magazine: And in the other direction? How do you find out about an aspect of traditional knowledge?

Miguel Angel Crespo: We maintain contact through our work in biodiversity. We are, for example, working permanently with community-based eco-tourism, systematizing information through field investigations -- the field investigations that the technical team carries out. For example, with the fruit fly. We are carrying out an investigation to see how we can control the fruit fly and we are carrying out this investigation in rural communities with the farmers.

Another example is the use of the trichoderma, which is a microorganism that we have used now for several years to control diseases in soil. Through the systematization of this experience we are able to corroborate advances within the communities where we work which support the bio-remediation, the recuperation of soils that have been degraded.

Small-scale farmers in eastern Bolivia

In Motion Magazine: When you work in the communities, are these primarily small-scale farmers?

Miguel Angel Crespo: Yes.

In Motion Magazine: How many hectares do they have?

Miguel Angel Crespo: It depends. Within the area of the valleys or on the Altiplano, a small producer is someone who has a quarter of a hectare, up to one hectare. In the case of the lowlands, there are small farmers who have 20-50 hectares which were given to them by the state as a result of the process of colonization twenty or thirty years ago.

In Motion Magazine: Colonization?

Miguel Angel Crespo: Colonization as a result of the Plan Bohan, which I mentioned earlier, during which rural peasant farmers from the Altiplano moved out to the Bolivian lowlands. At the root of these policies for the establishment of agro-industry, there was a need for manual labor for the harvest of sugar cane and cotton and many peasants came from the west, from the Altiplano. I would say that they were motivated by two reasons. First, because there was employment, agricultural jobs. And secondly, because the levels of minifundio (smallholding) became worse and worse.

These workers who came here to work temporarily have stayed. They organized in unions and asked for the government to give them land. The government, with the politics of populism in both military and civil governments, handed out thousands of hectares. Many peasant farmers received land in this process. They stayed and they are now small farmers of soy, cotton, sesame, beans, oranges, etc.

Indigenous farmers

In Motion Magazine: Are these mostly indigenous people?

Miguel Angel Crespo: Yes.

In Motion Magazine: Which indigenous people?

Miguel Angel Crespo: Mainly Quechua. Seventy percent Quechua and 30 percent Aymara.

|

|

|

The Salao community women's group "The 26th of April" has worked with PROBIOMA since it was founded in 1999. According to member Edith Rojas, they were particularly encouraged by PROBIOMA coordinator Rosa Virginia Suarez. The group was formed because as women they wanted to play more of a role in the community. They currently dedicate their work to the production of organic vegetables, each woman with their own piece of land. In this photo, group member Rosa Rueda, her daughters Ana Tejenna Rueda and Kelly Vara Rueda, and her grandson David Alexandro Morón.

|

|

|

|

Edith Rojas, member of The 26th of April women's group in the Salao community. She says the group has been good for its members because it provides good food to keep the family healthy and also provides a little extra income. It also has helped her independence. She added that as women in South America who for so many years have used agro-chemicals on vegetables and fruits (we) should organize ourselves, stop using the chemicals, focus more on health, and think about what we are eating and what we are applying to what we are eating.

|

|

|

|

Family-grown food being brought out to be loaded on to a PROBIOMA pick-up truck for a trip to the market.

|

|

|

|

A Crisol sunflower plant.

|

|

|

|

Cut sugar cane being transported.

|

|

|

|

Crossing the Guayacan River.

|

|

|

|

On the way home from school. (Click here to see a larger version.)

|

|

|

|

A billboard promoting education reform in Santa Cruz.

|

|

|

|

Basilica Menor de San Lorenzo, Plaza 24 de Septiembre in Santa Cruz.

|

|

|

|

Members of the Guardia Municipal in Santa Cruz.

|

|

|

|

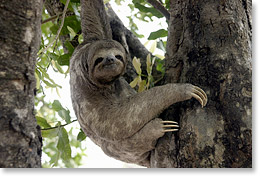

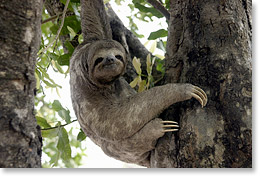

A sloth in a tree in Plaza 24 de Septiembre in Santa Cruz. (Click here to see a larger version.)

|

Forests and soy

In Motion Magazine: And the land they received, was it forest or was it already agricultural?

Miguel Angel Crespo: It was forest. There was a very big impact. Agro-industry promoted the deforestation of thousands of hectares of forest. And also the people of the Andean Altiplano did not have any knowledge about the management of forests. For them, to see a tree was to cut it down. Additionally, the export market demands mono-cropping of soya and sugar cane. There has been a very strong environmental impact on the Bolivian Oriente.

But, this reality combines also with the reality of the indigenous people from the Bolivian Oriente, the Bolivian lowlands, within their indigenous territories. They have managed to maintain within their territories, until now, a better management and conservation of their forests, resources, despite the fact that there’s a great amount of pressure from the timber companies and soy producing companies who want to enter into indigenous territories to produce soy.

To sum up, in the case of the Bolivian Oriente we can say that there coexist three different modes of production. First, you have big companies with thousands of hectares of soy, cotton, wheat, with concepts of agro-industry, mono-cropping, very much led by the export markets with a strong component of the Green Revolution.

Secondly, there is the mode of small producers, originally from the Andean region, who arrived over thirty years ago; people with who we are currently working on their process of reconversion to agroecology because they now don’t have anywhere else to go. This is their last opportunity, the last bit of land. Conserve that bit of land well or lose the land.

And thirdly, there is the mode, or fact, that these are indigenous territories in which there is a strong pressure from petroleum companies, timber companies, mining companies, and soy producing companies. Up until now, these territories, which have been declared original community territories, have been conserved according to traditional customs, according to traditional knowledge. In our work, PROBIOMA emphasizes this component of biodiversity so that there are conservation alternatives with economic benefits.

In Motion Magazine: What are the names of some of the peoples in these indigenous areas?

Miguel Angel Crespo: There’s more than 34 different indigenous peoples in the Bolivian Oriente. The largest, in terms of numbers, are the Guaraní. You will find them in parts of Paraguay and Argentina. Next are the Chiquitanos, the Mojeños, the Ayoreos, Yuracarés, Sirionos, Chimanes, Tacanas. There are many.

In Motion Magazine: If you were to put a number on the quantity of people PROBIOMA works with – how many would that be?

Miguel Angel Crespo: According to our calculations, indirectly in biological control we are reaching around 3,000 farmers. What they produce, the products, the food is benefiting up to half a million consumers. Of course, we also have direct support programs. In the case of responsible soy we are aiming to reach 2,000 producers and with other farmers, about 500.

Sustainable management of forests

In Motion Magazine: The two reasons to cut down trees are timber and creating land for soy?

Miguel Angel Crespo: Yes.

In Motion Magazine: Is that still going on? Is it being slowed down?

Miguel Angel Crespo: In the case of timber it is slower. Bolivia has had a forestry law for the last ten years through which has been established sustainable management of forests. Also we now have the Certificación Voluntaria de Bosques (Voluntary Certification of Forests). Bolivia is the first country in the world with certified forests – more than 2 million hectares.

In Motion Magazine: And you support it?

Miguel Angel Crespo: Yes. Rosa Virginia Suarez (co-coordinator of PROBIOMA) was one of the co-authors of the law. As I said, this law has led to the fact that Bolivia is now the leader at a world level in certified forest. Bolivia has the most certified forest, in terms of number of hectares.

In Motion Magazine: What is certified forest?

Miguel Angel Crespo: The CVF -- Certificacion Voluntaria Forestal -- voluntary forestry certification. It’s a certification that allows you to make a selective cut that comes from forests that are managed sustainably. Bolivia has 2,200,000 hectares of certified forest. Not even Brazil has a higher number. Certification of forests is based on certain criteria. This means that they allow a selective tree-felling process, selective both in species and size of trees so as to not have mono-tree felling, to maintain the biodiversity of the forest. It also is based on respect for indigenous territories, protected areas, national parks.

In Motion Magazine: In Brazil, they are still cutting away? The horror stories. It is not true in Bolivia?

Miguel Angel Crespo: No, in Bolivia we have managed to put a break on the process but it was very, very difficult to do.

In Motion Magazine: Was there a lot of participation of the people in getting that law?

Miguel Angel Crespo:There was a lot of participation between organizations, institutions, and companies, though the companies were the most reticent.

In the initial law they established the fact that whoever had a forestry concession must pay in taxes one dollar per hectare per year. It sounds very little, but most of the people who had forest concessions had ten thousand, fifty thousand, a hundred thousand hectares, which meant paying $50,000, which is a lot of money for someone in Bolivia. Many of these companies returned forestry concessions to the government and they just kept small concessions. Under these rules they subscribed to the certification process voluntarily.

This program of certification is very much linked to the international market because it gives an added value to the processed wood that you then export. Bolivia is now exporting doors, window frames, which come from certified forest. They have a great value on the market and the certification process is now paid for by taxes.

Native microorganisms

In Motion Magazine: Can you talk about PROBIOMA’s work with microorganisms.

Miguel Angel Crespo: At the global level, very little is known about the value microorganisms have. But, from the little we do know, microorganisms have actually contributed greatly to health advances. In the case of agriculture, we have seen that there are several microorganisms that already more is known about; that they are capable of controlling certain plagues and diseases.

Through an arrangement we had with a Cuban scientific center, we did several evaluations of microorganisms in the Amboro Park area. At the same time, we discovered many insects that were contaminated with microorganisms through natural processes. These two factors led us to see the possibility of isolating certain microorganisms, producing some sort of product that could be used to control plagues in agriculture, which would let us begin biological control.

In this way, about twelve years ago, we began the process of isolation, formulation, production of microorganisms for biological control. As a result of what I’ve just mentioned to you, and also as a result of the fact that in Bolivia there were already certain experiences of biological control more based on insects, parasites, we can say we are the leading organization in Bolivia working with biological control with microorganisms. Today, PROBIOMA has in our laboratory in San Luis a bank of over 450 native microorganisms.

Technological innovation

In the process of formulation of the microorganisms, we have had many problems because there is no recipe for formulation, no set way of carrying out this process. Or if there is a standard way, the biotechnology companies don’t share it. It is an industrial secret.

So, PROBIOMA has had to technologically develop, under the criteria we considered correct, a process for the formulation of microorganisms. And later we had to patent this industrial process to protect this technological innovation from the possible menace of the biotechnological companies. But, what we haven’t done and we never will do, given the bioethics of patenting of microorganisms, is patent a microorganism. We are against the patenting of life.

Currently, we are producing roughly sixteen different lines of microorganisms but we are always increasing our number of lines according to necessity and discoveries. It is a permanent process of investigation and technological transference.

Protection of seeds / recuperation of soil

In Motion Magazine: Can you talk about one product?

Miguel Angel Crespo: Trichoderma spp is a micro-fungus, a parasitic fungus, which means that it controls diseases produced by other fungi. This microorganism for us is a star product because it allows farmers to protect from disease seeds of any crop. You can use it with any crop. It’s used a lot in soy for the protection of seeds, also vegetables and other grains. This fungus allows bio-stimulation, germination of the plant. It controls diseases such as Campingoff. It is a grouping of different fungi which attack seeds. It protects against Aspergillus, which is a disease which attacks Brazil nuts.

We are currently carrying out an investigation of this in our laboratory. It increases the level of the rooting of the plant. And also we are currently finishing an investigation through which we have discovered what affects the process of bio-recuperation of degraded or contaminated soils, soils contaminated by agro-chemicals. This microorganism could contribute greatly to the recuperation of heavily degraded soils such as in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. We are hoping to publish this document in the next fifteen days and it will be in Spanish, English, and French.

Controlling Chagas disease

Another two microorganisms that we work with are Beauvaria Bassiana and Metarrhizium Anisopliae. With these two we have managed to control the vinchuca, which is the Triatoma Infestans (infestation) and the vector of the Chagas disease.

As I mentioned earlier, Chagas disease affects half the population of Bolivia. Three million people, almost half the population, are at risk of contracting Chagas disease. At the world level, there are more than 90 million people who suffer from Chagas disease. There are 100 million at risk of contacting Chagas disease -- in Latin America, fundamentally, in Bolivia, Perú, Argentina, Ecuador, México, Brazil, and Paraguay. Also, in Africa. And, with strong migration to Europe and the United States, they have found Chagas disease in people who live in these countries.

Chagas is transmitted through the bite of the insect through blood transfusion. Also, they have now discovered that it is transmitted from mother to child through the placenta, and that people who have drunk sugar cane juice which has been made from sugar cane where there was a vinchuca inside it and it was ground up, they will also find themselves contaminated with Chagas disease.

Chagas programs have three components. First, the improvement of housing because you find the vinchucas in the floors and the roofs of poor houses. It is necessary to build thousands of new houses and this requires a very large investment in poor countries

Secondly, in all the countries where Chagas is found the countries carry out fumigation of housing with chemicals such as Deltametryna and Alfadeltametryna, and these are chemicals against which the vinchuca have developed resistance.

And thirdly, preventative education programs and control programs, which they usually do with children. They give them the medication Bendamidazol, which is expensive and requires doses for many years. This medication stops Chagas from spreading much further but it doesn’t eliminate it.

Because of the situation (with the three components), some people are currently investigating possible medicines that could control or eliminate Chagas disease which are based on a virus called Trypanosoma Cruzi. In the last few years, they have started studying its genetic structure to develop from it a medicine. However, the problem is that in seven or eight years they have only been able to discover sixty or seventy percent of the genetic structure. It is likely that it will take another five, six years – and that is if there are funds and resources to carry out the rest of the study, as they doing in Brazil and Argentina. Further, the commercialization of this medication is another thing, with the pharmaceutical companies wanting to recover their investment, as has happened with the medications to combat HIV-AIDS.

Chagas from a social point of view

When PROBIOMA discovered that these two microorganisms (Beauvaria Bassiana and Metarrhizium Anisopliae) could control the vinchuca vector of the Chagas disease, we decided to carry out an investigation -- even though we didn’t have any financing -- an investigation into these microorganisms, more from a social point of view. Our investigation has now come to its conclusion, after eight years of work and the product is ready. But, the government doesn’t have the political will, the means, the resources to adopt this technology. It still has a stock of chemicals for fumigation that will last another two years. And, additionally, there are levels of corruption, economic interests, which don’t want biological control to be used.

Fumigation with chemicals is not a solution because the campesinos don’t want their corrals, their barns; to be fumigated; that is where they have their animals and the chemicals kill their animals or make their animals sick. But, these areas are where the vinchuca have their nests. We discovered in this investigation that the vinchuca often live in these barns, abandoned houses, also in caves where there are bats or rodents. Additionally, they live on plants in the forests surrounding communities and obviously they aren’t going to fumigate with chemicals there -- on top of being very expensive, the environmental impact would be very high. Furthermore, the vinchuca has developed resistance to the chemicals.

All of this we have documented and argued in many meetings with those responsible for the Chagas program in Bolivia. But, they insist on maintaining their policies and that suggests to us that there exists other interests which are greater than community health and the environment. They don’t want to recognize the scientific contribution that we are making to this program.

Meanwhile, we receive many emails from Mexico, Argentina, Chile, and Brazil asking if we could do something like this in their countries -- which leads me to the conclusion that nobody is a prophet in their own land (laughs).

GMOs: a lack of understanding of biodiversity

In Motion Magazine: What do you think of genetically-modified organisms?

Miguel Angel Crespo: I think they are not a solution because there exists in the world a great richness in biodiversity which doesn’t require genetic manipulation to fulfill a task. For example, Bolivia has more than three thousand varieties of potato. It is the center of origin of potatoes on the world level. Among these three thousand species there are very many different varieties that are resistant to diseases, droughts, floods, insects.

On the global level, there are hundreds of different varieties of banana. I have visited the germplasm bank of bananas in the University of Louvain, in Belgium. Seeing that, one can realize that there must be many different varieties that are resistant to different plagues, diseases, climates.

To carry out a genetic manipulation shows a lack of understanding of the richness of biodiversity. It is to liberate risks and we don’t know what they will bring us in the future. There is evidence that they can alter the immune system and the genetic structure. The limited introduction of genetically modified soya in Bolivia has been a disaster in terms of lower levels of production and higher susceptibility to roya, which is a disease that attacks soy; and also because it requires more herbicide use.

For us, the introduction of transgenic soy is not a solution. We have compared output and costs between conventional and transgenic soy in two scientific tests, in both summer and winter. Transgenics are not viable either economically or environmentally and that is why we are promoting the reversal of the law that authorizes the commercialization of genetically-modified crops.

Soy, GMOs, and trade

In Motion Magazine: Can you talk about the soy project?

Miguel Angel Crespo: Bolivia is one of the eight largest soy-producing countries in the world. Soy in Bolivia is the second largest income for the country (in foreign currency) after hydrocarbons, about $450 million annually in exports.

In Bolivia, soy was first introduced in the ’70s but was produced on a large scale in the ’80s. Although it is one of the very important crops for Bolivia, on the global level Bolivia only contributes .7 percent of the global production of soy. Inside the Mercosur countries, Bolivia’s contribution is 1.5 percent of the soy production. In all, in Bolivia, around 900,000 hectares of soy is planted annually.

Soy represents a relatively high percent of the gross domestic product of Bolivia. However, the market for Bolivian soy is mainly in the Andean community of nations. Bolivia sells a large quantity of its soy to Venezuela and Colombia. But, due to the Free Trade Agreement being signed between Colombia and the United States, Colombia will stop buying around 300,000 tons of Bolivian soy. And, given Bolivia’s geographical situation, the costs of transportation for Bolivia are much higher than in countries like Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay -- the cost is around twice the cost in these countries. Bolivian soy is not as competitive as the soy from Brazil, Argentina, or Paraguay.

Additionally, the soy boom has become a menace to large areas rich in biodiversity, national (protected) parks, indigenous territories. And last year, under great pressure from the multinational transnational companies, the previous government authorized the introduction of genetically-modified soy in Bolivia.

Socially and environmentally responsible soy

In PROBIOMA, we have always maintained that Bolivian soy is not competitive in the international market because of the very small amounts of soy that we produce in comparison with other countries. For that reason, we have always stated that Bolivian soy should compete on the international market with certain characteristics that are qualitatively different. Given that Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Brazil produce large quantities of genetically-modified soy, we think it is a great error that Bolivia should also produce the same genetically-modified soy.

For these reasons, we have developed a proposal with indigenous and campesino organizations, and some Bolivian soy companies. This proposal is a set of criteria for social and environmental responsibility in the production of soy.

These criteria are based on: respect for indigenous territories, protected areas, Ramsar sites (the Convention on Wetlands, signed in Ramsar, Iran, in 1971, is an intergovernmental treaty which provides the framework for national action and international cooperation for the conservation and wise use of wetlands and their resources. http://www.ramsar.org/); respect for the use of soils; no use of transgenic seeds; the gradual reduction of the use of agro-chemicals; substitution of chemicals with biological control; and ethical labor agreements. With these criteria, Bolivian soy would have a different identity compared with soy from other countries.

We presented these criteria to the big soy producing companies at a global level, such as Unilever, the Maggi Group, and Coop with the idea that these could be incorporated into their business policies -- that they have positive social and environmental impacts in Amazonia, the Patanal, the Chiquitania. Also, we have shown these criteria to NGOs from Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, and Europe. We have managed to establish a soy platform that brings together NGOs and small-farmer soy producers.

In this way, the Program of Responsible Soy Management was born. We call it responsible because we don’t believe the mono-cropping of soy can be sustainable. The program is currently in operation and we are hoping to reach two thousand small soy producers. We have been able to contribute towards the creation of an association of small soy producers in Bolivia, who have managed to export responsible soy to Venezuela in the framework of what is now the Trade Agreement of the People, which is an alternative proposal between Bolivia, Venezuela, and Cuba to ALCA (Área de Libre Comercio de las Américas / Free Trade Area of the Americas, the system of free trade agreements promoted by United States.)

Organizing for responsible soy

Our proposal has also had an impact on the world soy roundtable organized by European food companies, European banks, and biotechnology companies. Because of our proposal they have changed their name from the Roundtable on Sustainable Soy to the Roundtable on Responsible Soy. We have been successful in that now this roundtable does not consider genetically-modified soy to be included in the criteria for responsible soy.

Another achievement is that this roundtable of large companies has established a moratorium such that as of 2007 they will not buy any soy that comes from land that has recently been deforested in the Amazon, in the Patanal, the Chaco. This is a half victory because we want these companies to agree not to buy soy that comes from land that has been deforested since the year 2003.

Next, we are going to struggle for this roundtable to create a committee to ensure that the roundtable has a much greater participation of small soy producers from the all the producer countries of the world. In this regard there exists a greater commitment from the large companies and banks to respect the criteria on social and environmental responsibility in the production of soy.

I was in Sao Paulo just last week at a meeting and attending were not only small producers from Mercosur but also small producers from China, India, and Indonesia. In this way, we want to create an articulation that joins the small soy farmers from all over the world to pressure the large companies and banks.

|