|

Interview with Nora Castañeda

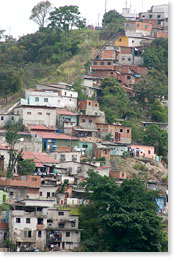

President of the Women’s Development Bank Making women sovereign and participative: Becoming the protagonist of their own reality Caracas, Venezuela

In Motion Magazine: Please say who you are and what your position is. Nora Castañeda: I am a woman, first of all. My name is Nora Castañeda. I am married. I have three sons and one daughter. I have one grandson and two granddaughters. I am an economist with a postgraduate degree in public administration and economic development. I am president of the Bank for Development of Women, and previous to this position I was a teacher in the Central University of Venezuela for thirty-three years. I have been many years in the movement for women and that’s why I support the human rights of the female human. Now, in my position as the president of this bank for women I address my work towards all the women who are in an impoverished condition. In Motion Magazine: Does the bank have customers or members? Nora Castañeda: The term for people who come to the bank is users. Because we, here in the bank, help women who are in a poverty condition, they use the services of the bank. They use the services and they are the providers of the services. They are not exactly clients or members but users. In Motion Magazine: How does the bank work? Nora Castañeda: The bank works with two different types of services: financial services and non-financial services. The financial service is micro-credits which are given to the women, in their communities. For example, the bank could go to a community, such as La Barinesa, and offer our services, talk to the women, and try to help them with their activities. To offer them some resources. The women are the ones who say if they want to work with the bank or not. They make the decision. The non-financial services comprise, more or less, training. How to use resources. Some technical support. Follow-ups on how their business is doing. Helping women through the whole process. Giving them the money or resources they need, then training them to use them appropriately through the establishing and developing of their business. Popular economy and participatory communities When we arrive in a community, we give some workshops with the women of the community. The first workshop we organize is on popular economy. Then we give a workshop on participatory communities -- how the community can participate in different aspects of the community and how they can diagnose the conditions of the community. The first step is to help the community in the creation of micro-projects for investment. Very simple projects, but ones which are possible to achieve, which are easy to handle for these women, specifically in their poverty condition. Then we address issues of reproductive and sexual health for women because this is very important. We emphasize the fact that women have the right to live a life without violence. We also work on women’s self-esteem and leadership -- how women can become leaders of their own community. We try to work with all the aspects that contribute to making women sovereign and participative in their communities, in their economies. Not managing poverty but overcoming poverty We don’t have the vision that this is a business for us. We are not seeing these projects as a way of making money for the bank. That is not the interest of the bank. What we really want is that all the people working with the bank have the possibility of making money for themselves. We don’t want the bank managing poverty but overcoming poverty. That is why we offer the minimum interest rate, 12% per year, a fixed rate, for the non-agricultural activities, and for agricultural activities it is 6%. We can legally even go down to 1%. Apart from the fact that we trust in the word of the people who take the credits, we are trying to manage a social concept of the economy. We don’t want to take money from the poor people who don’t have money, but help them to overcome poverty. A relationship of exploitation or a relationship of mutual-contribution In Motion Magazine: Could you go into more what you mean by popular economy? Nora Castañeda: Yes. The economy itself is defined as a social science and as such it studies the social relations among humans when they are producing their material life -- when they are producing their own resources to live, creating their material goods. Now, those social relations among humans, based on production, can be of two kinds: a relationship of exploitation or a relationship of mutual-contribution. Here, at the bank, we make all our efforts to contribute to, to develop, a mutual-help economy. A kind of economy in which everyone helps each other based on everyone cooperating in creating this kind of economy. For this purpose, we give all the resources possible so that the communities can work in this kind of economy. An economy in which mutual help is the most important thing. That is what we call popular economy. In Motion Magazine: What are some examples of some of the projects that you contribute to? Nora Castañeda: First, we have created something which is called an associative economic unit, which is a group of women. These associative economic units work specifically with women in extreme poverty. Along with their knowledge of how things work and the knowledge of the women in the community and their resources, the bank has created a dialogue which we call a knowledge dialogue. We give what we know about creating micro-businesses and the women contribute their knowledge about the community, the resources that they have or they don’t have. We say this is a knowledge dialogue because we are always inter-changing different kinds of knowledge. In the south of Venezuela, in Bolivar state, a state which is very rich in different natural resources, such as iron, gold, aluminum, diamonds, there is a very important indigenous community -- the Pemon. But they are in poverty conditions, always, always. They are in a very difficult poverty situation. The bank went to La Gran Sabana (in Bolivar state), which is a very important area, a national park, and there met with the indigenous group, the Pemon. They established a dialogue with the women of the Pemon community and also the chief of the community. The work of the bank is addressed to the women, specifically, but they also have to meet with the chief. Also, in the state of Bolivar there is an important corporation, which is the Venezuela Guyana Corporation. Guyana is another name for this area and Venezuela Guyana is a national public company, owned by the Venezuelan government, which extracts the natural resources -- iron, etc. This corporation, it’s most important objective is to contribute to the development of this area -- Bolivar state, Amazonas state, Delta Amacuro state, and the southern parts of Monagas state and Anzoategui state. All of the southern part of the country works with this corporation, which helps the development of the whole region. The bank established a dialogue with this corporation, Venezuela Guyana, and, in order to merge their forces with the Pemon community, they gave 70 credits to 70 women and one credit to one man. The bank achieved an agreement with the company and we gave these possibilities to the Pemon community, to the women, specifically. But who really decided what was going to be produced, and how, and where, and for whom, and what product they wanted to develop were the women from the Pemon community. They made the final decision on how, when, and what products. How they wanted to use the resources they were given. In Motion Magazine: How large are the groups of women? Nora Castañeda: The groups are between five and nine people. It can be a family or not. Women can bring men from the family to the group if they want. But most of the people of the group have to be women, and the coordinator of the group has to be a woman. The Bank’s vision is women are the poorest among the poor people and the bank works for these women. Trying to provide everything they need. And in the case of this community, as I said, they were 70 women and one man. But now the People’s Bank, which is another bank, has brought more men to this group. They work more with men. Handicrafts, spice, and eco-tourism Anyway, these constituted groups mainly produce handicrafts and a special spice made out of ants, termites. It is very spicy. They use the venom of big ants and termites. They also work with other foods and agriculture produced in the region. The Gran Sabana, as I said, is a national park and is a very wide and long extension of the country and the people have created inns for tourists. They are developing the tourist trade. They work with eco-tourism. In these inns there are no beds, there are hammocks. You are in the region, in contact with nature. You don’t sleep in a bed, you sleep in a hammock. It is very different. It is authentic, from the region. A lot of European tourists come to this region because it is a magical land. Very dark nights. Complete silence. Beautiful days. Very long prairies -- that is why we call it the Gran Sabana. Many rivers. You have to go there. Misión Mercal and “chains of production” In Motion Magazine: I’d love to. What is an example of a project in the cities? Nora Castañeda: In the cities, mainly we work with handicraft projects and manufacturing. People manufacture different kinds of things, for example, clothing, wool coats, shoes. Also fast food, but not the usual fast food, rather food for fast sale which is very natural, without chemicals. We work a lot with sweets, authentic special desserts. In Motion Magazine: Do they sell directly to the public, or to someone in between? Nora Castañeda: In the majority of cases, the women sell the products they make directly. But now there is a special Misión of the government, called Mercal, and the objective of this mission is distributing all these different products women make with their own small companies. In this mission there are some establishments only for food and the women are given some stands for them to sell directly their own products. They don’t produce a lot of products because they have small businesses and they don’t have the capacity to produce a lot, but as several women producing the same thing, or somewhat different products, they are now creating something called “chains of production”. They work all together to produce the same thing, marmalade or something, and they sell it in this Mercal establishment. These chains of production have been created from the beginning to the end of the product. From the agriculture, the farming of the product, to the transformation, commercialization, and marketing of the product. And then, of course, getting the product to the consumers through the Misión or directly, in their small businesses. In Motion Magazine: How many people have you involved so far? Nora Castañeda: Approximately 44,000 people. Ninety-six percent women and four percent men. In Motion Magazine: So do people ever come to you with a project or is it only you going to them with a project? Nora Castañeda: For the purpose of getting to all the communities and bringing out all the ideas and possibilities, the bank has a network throughout the country of training staff. In every state of the country we have different training staffs and these women are in charge of creating alliances with different community organizations -- with women’s organizations, or universities, or the mayors of different cities, or the governors of different states. They establish strategic alliances with these important parts of the community so they can get to the whole community. In each state, each part of the country, a part of the training staff goes to the community to bring the projects, the ideas to help women create their own projects. Those are to specific communities, but we want to get to the whole so we make these connections with the important people in each state. In Motion Magazine: Is this an example of the participatory communities you mentioned earlier? Nora Castañeda: In general terms, traditionally, the economy has been used to exploit human beings and to discriminate among human beings. Human beings have been for the service of the economy, working for the economy. At the same time, these economies, produced by all human beings, were only for the benefit of a few people. The economy was the way to use people to produce for the benefit of a few. I feel that these kinds of projects have transformed a little bit what the concept of an economy should be, or is. Instead of using people, or exploiting people, people more are participating in the process of the economy. We want to transform, reverse the process, to make the economy work for human beings and not the other way around. The protagonist of their own lives In the context of our country, in which the majority of our people are poor, we work specifically with the women, who often have to be both mother and father because there is a lot of irresponsible parenthood, especially among men. At the Bank, what we try to achieve is to enhance and emphasize the human right of women to be an important person in society, to be the protagonist of their own lives. We try to improve the quality of life of these women and therefore the quality of life of their families, their children, their husbands, if they have husbands, their parents. They will have a better quality of life through the women who work with the bank. This is what we call a popular economy when the economy is working for the mass of the people and not for a few only. We want to get the economy to work for a large amount of people and not for a few. The women who work with this bank never before had the possibility of having credit or of having access to these possibilities because as they are poor they don’t have a warranty, a pledge, something they can offer to back up the credit. The way this bank works, we don’t require these securities. We trust the women’s word. That’s all we ask. Their word as a working woman. The women’s movement in Venezuela In Motion Magazine: What were you organizing for when you were in the women’s movement? How does that compare to now? Nora Castañeda: Before 1999, I was involved in the women’s movement. What I did was research. Research about women’s world reality, the real conditions of how women lived throughout the country, and specifically in the Andean region. This research allowed me in the women’s movement, and also as an economist, to work with women’s organizations, to know better how they worked. As a teacher in the university, I took information from this research to develop, elaborate my classes. But we, the women’s movement, didn’t have the power to change or implement new laws. We did create projects but they didn’t become real policy. And the policies that were established didn’t meet what we had in mind. These related to opportunities for women, reproductive and sexual rights, the right to a life without violence, labor rights, correspondence between salary and the work women do. We created these projects but they didn’t become policy. It was only in the year 2000 when we could actually make these ideas laws, having a state budget and disposition to use the budgets to implement these new policies. Of course, these policies applied to all the people, but specifically the poorest women.

In Motion Magazine: So what happened in the year 2000? Nora Castañeda: In 1998, President Chavez won the election and, in 1999, the president opened the possibility of the Constituent Assembly to create a new constitution. Our people, the country, had had centuries struggling and fighting for the right of becoming sovereign, of becoming the protagonist of their own reality. In 1999, when the president called for the possibility of making a new constitution in which indigenous groups had the opportunity to participate, and women, and farmers, they all made their best efforts and began to work for this purpose. To create a constitution in which they were all included. The Constituent Assembly was held here, in Caracas, but all the people of Venezuela were re-united, and began to move, to participate, in order to achieve a constitution which would reflect our duties and our rights as citizens. Women achieved many different things within the constitution, many new rights. But the one thing that was most important was, in non-sexist language, the very right to be the protagonist of our lives, which is called in English, because we have borrowed your term, empowerment -- to give power to the woman to be the one who determines her own life. The Women’s Development BankOn March 8 of 2001, International Women’s Day, the president founded this bank for the development of women -- The Women’s Development Bank. And of course all the research we had done before and all the projects we had, the knowledge we had piled up though the years, the achievements we made at the Beijing Conference, all these things we had in mind, we could finally implement them here at the bank. To work for women. The best interest of the bank is to help women in different ways, not just give them money, micro-credits. If we just gave them money the women would continue to be poor, but now with debts, as micro-credit implies debt. The real mission of the bank is to emphasize the role women must have in the society. Why do we always say women? Why do we always address women? Because we consider women to be one of the most important parts of the family. The most important one. Because women are always thinking about others. Always working for others. Their children, their parents, their husband, the whole family. Women are the strong part of the family and through women we get to the people, because they are not thinking about themselves but working, getting things done for others, for their families. That is why the mission of the bank is not only to give money but to create a consciousness among women of how important they are to their families, to the development of the economy of their families, and therefore of the country. From representative to participatory democracy In Motion Magazine: Usually people come to a bank. Is this a unique idea in the world, of going to the people? And, also, is this a form of sustainable development? Nora Castañeda: Yes and no. We have always thought that officials, people working for the state, for the government, should go to the communities because they are the ones who serve the people. Therefore they should look for and approach the people and thus transform the community, the base of popular power, as the people make decisions. How can the poorest indigenous women in the state of Amazonas, the southernmost state in the country, come all the way here, if they are so poor, to ask for a credit? There are not many roads down there. They have to come by river. It is very expensive because gas is very expensive. It is very difficult to come all the way here. They have low incomes. Before, there were politicians who came here and took money from the government on behalf of the community but didn’t deliver that money to the community. The people had no power at all because democracy was only representative. The politicians represented the people, but not really. This person didn’t serve the people. The democracy that is in the process of being built in Venezuela is participatory democracy. It has to be based on the people’s power. The president says we have to give power to the people. If the people organize themselves, and they create a project, present a project, and demand that the state, the government give them the resources to achieve these projects -- that is different from the politician who goes and asks for money, and comes to Caracas, then doesn’t give the money to the people. This is different -- participatory democracy. Apart from this, there is a way to supervise what is done with the money. The people can go to a specific place and they can know what has happened with the money. They are in control of their money. They can demand that the promises that were made are kept. As for part two of your question, I think this is a form of sustainable development. In fact, with the trainings, the staff network throughout the country, we can go, for example to La Barinesa, and we can establish new connections in the community. For example, Miguel Angel Nuñez can be an ally and we can establish connections with the governor, and the university, with different organizations. We can really know, we can collect, the information from the community. What the community really needs. We will adapt our services to what the community needs. This is a form of sustainable and sustained development. Avoiding any kind of aggression To close, all this is a part of a utopia, a dream, and the dreams haven’t ended yet, nor history. We are trying to achieve those dreams and there is a big distance between what you dream and the achievement of that dream. But that is what we are trying to do. Based on what the president says about giving power to the people, we will create a great country, and not just Venezuela but all Latin America and the Caribbean also. We strongly believe that all dreams are possible and for achieving those dreams we need that all people from around the world help us. From the people of the U.S. we don’t need money, necessarily. Instead we need help by avoiding any kind of aggression that might damage our dreams. Maybe by building and making those dreams come true we can make the dream of Martin Luther King come true. Published in In Motion Magazine April 30, 2005 Also see:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2018 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |