|

Interview with Rosy Barrios of La Red

Working to Rebuild Ourselves San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico

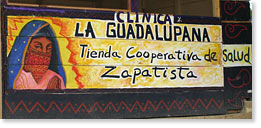

Rosy Barrios: My name is Rosy Barrios, and I come from the municipality of Motozintla, on the border with Guatemala. I’ve been in La Red (The Network) for two years. I’m 19 years old and I work here because for me it’s not work, it’s a responsibility. I have to teach and to learn how to defend human rights, especially in the communities. There’s very little knowledge here about what human rights are, especially about women’s rights. By exerting the right to free determination In Motion Magazine: What is the human rights situation now in Chiapas? Rosy Barrios: The human rights situation is that it’s quite hard to say that human rights are being respected here. It’s the reason we’re here, because of the lack of access to justice. Crimes go unpunished. There’s always injustice, especially for the indigenous people, because the government knows that the indigenous people aren’t aware; they haven’t been educated about human rights. Sometimes they think this is just the way life is, that you don’t have to say anything to the government. But, ever since the Good Government Juntas were created (by the EZLN/ Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional), I believe the human rights situation has been changing somewhat. Not a lot, it’s been a slow process. But, I believe that by exerting the right to free determination in the indigenous communities, to autonomy, they’re doing a lot. They have their own internal rules in the communities. How to punish someone. Not to the point of putting them in jail, but they punish them peacefully, as they say, by resolving problems peacefully. The Zapatistas have their own laws In Motion Magazine: What is the difference between rights with the Zapatistas and without the Zapatistas? Rosy Barrios: I believe the Zapatistas have a lot of advantages, because the government respects them. It recognizes that they are an organization, a very strong autonomous government. The government has recognized them even though it has introduced some programs to divide the Zapatista peoples. The difference is that the Zapatistas have their own laws. When there’s a problem, people go and lodge a complaint with the Good Government Juntas. I believe the communities have their own method of applying their own laws, and they can reach judgment among themselves. In Motion Magazine: How many communities does your work involve? How many villages? Rosy Barrios: There are about 10 villages or communities in my area of work. I have compañeros who deal with 20 or 30 communities sometimes, and so it’s difficult, no? In addition, when they need the presence of a human rights defender, sometimes the communities are quite far away. Also, we aren’t paid here. The community is responsible for us. In Motion Magazine: How many people live in your community? Rosy Barrios: Right now, around 8,000 persons. My community, my municipality, was declared a city, but we don’t see it as a city. For us, it’s still a community, a municipality, but the government declared it a city because there’s supposedly a lot of people. They want to introduce projects for everything having to do with Plan Puebla Panama. My municipality is supposedly scheduled to get a dam, and the people are protesting. They say they aren’t going to allow that because it’s our land and the government has no right to introduce those projects without consulting the people. It’s a right we have and the government has always violated that right of the communities to consultation when they introduce projects without thinking about the consequences they have in the communities. In Motion Magazine: What is the Plan Puebla Panama? Rosy Barrios: The Plan Puebla Panama is the project which is being introduced all over Mexico and in what are called the Third World countries. It’s a project which has to do with infrastructure, like building bridges, airports, highways, dams, affecting all the communities. In Motion Magazine: Is it having a serious effect in your community? Rosy Barrios: Not right now. Right now, the serious problem is the problem of land, because with the reforms to Article 27 of the Constitution it became easy to privatize lands through a program called PROCEDE, the Certification of Ejidal Lands Program. The government is trying to make people believe they’ll have the right to be owners through this program. In the communities, the people respond as communities. They decide all together what is to be done with the land. Whether they, all together, are going to sell it to or not. No one is the master of the land. They are all masters of the land. This PROCEDE program is dividing the people, because they are participating in the PROCEDE program which will make it much easier for people to sell it to those persons who come in and buy it than it will be to [sell to] people from the same village, from the same community. The people who have a lot of money are going to hoard these lands. They’re going to be landlords again, or caciques. Right now, many people have accepted that program, but also there are people who are in resistance to this. They know what the effects of this program are going to be, so they’re protesting. But the majority of the people have accepted that program. In Motion Magazine: How do they protest? Rosy Barrios: By telling the government that they don’t want PROCEDE. Also by giving workshops about PROCEDE, about what PROCEDE is. When someone goes to a community and asks them what PROCEDE is, they don’t know. So we provide training about PROCEDE. This is all quite important in the communities, knowing what its purpose is. In Motion Magazine: Can you tell me about the founding of La Red? Rosy Barrios: It came about as a result of all the human rights violations and arbitrary detentions, the illegal detentions. The Red was created in 1999, although some compañeros had already been training since 1996. It was in 1999, when the Red was created as a non-governmental organization. We saw an opportunity to put together a program so that people from the community could come and receive training every month. We stayed in the office here for three days, and they gave us workshops on penal law, international law. We’ve also looked into the rights of the indigenous peoples. The Red’s work in the communities is supported by the people. It’s supported by the community itself. The people named us to come and represent them. To take the information and also to train them. To tell them what their rights are,. When their rights are being violated, and how we can help them. We came and they trained us to take the information to the communities. Right now, we have 27 human rights defenders. They’re in the Northern region, the Central region, the Selva region, and I’m from the Sierra region. At the moment, we have four women, and the rest are men. That may be because the compañeras don’t have many opportunities to go to the communities, because many of them are married, or the authorities don’t give many of them permission, or they can’t come to be trained for a particular reason. But we recognize the need for more women here in the Red, because human rights are for everyone, not just for men, but for women too. As I said, we have four women. We’re working alongside the compañeros. We come each month to participate in our workshops just like them, and we return to the communities. We come, again, the next month. The Red pays for travel to and from the communities, and we have food here, and so we stay right in the offices. That’s how we are right now. The soldiers, the paramilitaries, the vote buying We believe the Red has played an important part in the communities. Right now, we see that the soldiers and paramilitaries have, to a certain extent, stopped violating human rights. The people won’t allow it now. The people know when soldiers are violating their human rights. The soldiers have, to a degree, stopped the human rights violations -- legally, as we say. But there are the violations of collective rights, like the new government programs which are dividing the people. For example, with the program that gives help to the countryside, its purpose is to have people belong to a political party, to support a political party, and right now more than ever with the elections that are going to take place in 2006. A lot of that is happening. The programs with money, with food, with cattle, so people will belong to this party, or support that party, or that other party which is going to win the presidency. That divides people a lot because there are many people who don’t agree with it. Those are human rights violations because an individual has every right to decide who he’s going to vote for, who he’s going to trust to govern him. But we see that it’s always been that way. Governments never respect that right. They’ve always tried to buy votes. But there’s something else that’s important. The people who are Zapatista in the autonomous communities, they don’t vote, because, as they’ve said, they are never going to trust the governments. Because everyone is equal, there are people who are against them, who say voting is an obligation. But they respond, “Why should we vote if the government has destroyed us? They’ve come to destroy nature. Why are we going to vote for someone who’s going to rob us of our rights, for someone who wants to steal our lands, for someone who wants to steal everything we have?” They say they aren’t going to vote. And that’s very important because that way they’re challenging that government which is going to govern us, that government which is going to be in the presidency, supposedly governing us. They have that right to challenge it if it’s not fulfilling its obligations; if it’s violating the rights of the community, of the peoples, and especially of the indigenous people. They tell us we aren’t lawyersIn Motion Magazine: Do you work for individuals or for groups of people, if someone has a problem? Rosy Barrios: It depends on the person who’s going to take his case. I haven’t, in fact, taken a case like that. I’ve made a denuncia, and I’ve gone to the Public Ministry, but I’ve taken a case to other compañeros if they’re more knowledgeable, if they have been in the organization for a few years. I have many compañeros who have the knowledge of a lawyer, but the problem is we don’t have professional certification. When we go to the Public Ministry, in front of the judges, the first thing they ask us is for something which is a certification, which recognizes us as being lawyers. But we don’t have it. Many of our compañeros don’t have a primary education, the basic education we should have. Many people here come in without knowing how to read, without knowing how to write. Here we end up learning a little about how to read and all that. When we go to a Public Ministry they look down on us. They tell us we aren’t lawyers. We can’t be here. But the compañeros have responded well to those criticisms, and they have always followed through with the cases until they’re finished. When there are detainees, they help them. In Motion Magazine: What method do you use the most, the courts or demonstrations? What forms of resistance do you use here? Rosy Barrios: The form of resistance, more or less, is we go to a court if we can help the person. There’s an article in the Constitution that says people who aren’t lawyers can participate by offering evidence, investigating, being named as a person of trust by the person who’s detained. That has been our guarantee for presenting ourselves as persons of trust in front of the Public Ministry, in front of the court; and for defending that case with help from our lawyer, Miguel Ángel, who is our advisor, Miguel Ángel de los Santos. When the case is really serious, then he appears. Since he’s a lawyer, it’s easier for him to go in. With his help, and with ours, we do the work together. Progress: education, healthcare In Motion Magazine: Is it possible to compare the conditions of 10 years ago to those of today? Rosy Barrios: From my point of view, I don’t have a lot of experience, I’m too new, Before those ten years, it had just, at the best, started to appear. But it depends on the history they recount. Every day the situation is getting worse. It’s more difficult, worse, for the people who don’t belong to an organization; who aren’t fighting for their human rights. For the people who are organized, this new route has been quite important. For the autonomous communities, I believe they’ve been doing very important work. They say the situation has changed a lot because in the indigenous communities they are claiming the most important right, which is the right to autonomy. Even though the government has tried to say that we’re violating constitutional laws, that we’re violating their government; that we’re offending them. But I think that the work the indigenous communities are doing has been quite advanced. They already have autonomous education, autonomous healthcare, in the communities. They’re working with each other. And that’s very important work because it’s difficult to get education in the communities. The majority of the indigenous have no education, and now, with autonomous education, many people already know how to read, the basics, to write, at least. Many very old people don’t even know how to read. They are people who use an indigenous language; who speak a different language than Spanish. The education provided by the government isn’t going to be in an indigenous language, it’s going to be in Spanish. And, since many indigenous people don’t know how to speak Spanish, then they’re not going to understand education in Spanish. Autonomous education is, therefore, quite important, and I have seen it make a lot of advances in the indigenous communities. Also, autonomous healthcare: if there is a clinic or hospital in the communities, then there aren’t doctors, there isn’t any medicine. The doctors work without medicine in the communities. So, they’re trying to bring back traditional medicine, like plants. That is all very important work in the communities. There have been many advances made in the autonomous communities. In society, when people belong to political parties the situation is difficult, more and more difficult, because we’re always dependent on the government. We’re always at risk of suffering violations of our human rights. The denuncias about detentions are always going to be made to the federal government. For me, I believe a lot of progress has been made in autonomy. There has been a lot of progress made in the work of the communities.Now, with the European cooperatives which are exporting goods to other places, that’s another way of resisting, of helping us, of being in solidarity with people from other countries, from the United States, Argentina, Italy. All those countries have helped a lot in marketing. For example, Chiapas produces a lot of maize, coffee, and right now, with the women’s crafts and their work, there has been a lot of progress economically. The women are also participating. They’re working along with the communities, even though women’s rights still don’t exist. They’re being respected. But as it is there’s still a lot lacking. Progress: revolutionary women’s law Right now, women’s rights in the city, in a big town, are quite difficult because women have always been subjected to government politics and women’s rights have never been heard. I’ve given workshops on women’s rights. I gave a workshop on the revolutionary women’s law -- which is the Zapatistas’ -- and the women liked it a lot because the Zapatista revolutionary law says that women, women’s rights, should be respected. A woman shouldn’t be discriminated against for being a woman. A woman can have a military rank. She can be an insurgenta, I don’t know, whatever she wants., She is free to decide what she wants to do. As far as the women go right now, they know their human rights but what is happening is that they lack them in fact; those actions which can be taken so the women have all those rights, so their rights are respected. Caracoles / Good Government Juntas In Motion Magazine: Can you explain how Caracoles work? Rosy Barrios: I believe all of us know how the Caracoles work. The Caracol is made up of different governments, of the autonomous councils. I believe the Caracol’s work is to receive different international and national persons and to talk with them, to learn about their methods of struggle; to let them know about their methods of struggle as well. They are working and informing other people who come from other countries. I believe that’s the work of the Caracol. The Good Government Juntas’ work is more internal, I think. Meaning it has more to do with their communities, with their people, with their support bases, including me. I think the Good Government Junta has been functioning quite well because there are people who belong to political parties who have gone there to resolve their problems. They’ve gone to ask the Good Government Junta for help. And that’s quite important. I think that the people who are gaining the most from this struggle are the people who don’t belong to the Zapatista Army, because the people who are Zapatista already know how to defend themselves. It’s not easy any more for people to come and deceive them, because they understand their struggle. They are aware of it. So, more people from other parties go to have their problems resolved there. Almost the majority of them are people from other parties like the PRD (Partido de la Revolución Democrática), the PAN (Partido de Acción Nacional) and the PRI (Partido Revolucionario Institucional). The Good Government Junta’s work is very important. It’s a right they have claimed; defending their own rights in their communities. They have said, “We don’t want to be independent, but to be part of Mexico; for our rights as indigenous to be recognized, that our rights are respected.” That’s what I think. In Motion Magazine: What is autonomy? Rosy Barrios: I think we all know autonomy. It’s a dream we all have. Autonomy exists in different ways. Autonomy is how we’re going to govern ourselves. How we’re going to make our laws. What the rules in our communities are going to be. I believe autonomy has different ideas. Everyone has a right to autonomy, but we also have the right to autonomy collectively. In the communities they work like that, together, not individually. I believe collective autonomy is stronger than individual autonomy. If someone struggles for individual autonomy, I don’t think we have as much strength. But if we struggle for our collective autonomy, our autonomy in the community, I believe it’s quite powerful, because that way we decide how we’re going to govern; how we’re going to work the lands. It’s deciding what we are going to do in our community. In Motion Magazine: The struggle for land here has a long history, going back to the Spaniards and before. What is the connection between the struggle for land and autonomy? Where did the struggle for autonomy come from? From the struggle for land? Human rights? Rosy Barrios: I believe the struggle for autonomy came from human rights, because land is part of a right, of a human right, the campesinos’. There’s a saying here that “the land belongs to the one who works it.” Land is part of human rights, collective rights, of the rights of the people, and autonomy is also a right. I think autonomy is very important. Autonomy is what defines everything in the community, our own autonomy. I believe land is another right, but I believe it would work quite well with autonomy. I believe that if someone is working their land, and if someone comes and takes it away, then it’s theft. It’s a dispossession of his right to land. I believe autonomy is a very important right in the communities which the government has tried to set aside. Now, the government says it respects the right to free determination and autonomy, but under a legal framework. That means that it is going to decide what autonomy is going to be like, that it is going to decide when autonomy is going to be. It is going to decide if autonomy is legal or if it’s illegal. I believe autonomy isn’t someone saying what it’s going to be like and all that, instead we ourselves are going to decide autonomy, self-governing, ourselves. The government doesn’t have any right to say, to force us to say, what autonomy is or what it’s going to be. It can’t impose regulations that say what autonomy is going to be like, since we know that it (the government) never acts in favor of the people, of the communities. Free trade markets / daily sustenance In Motion Magazine: Do the people in the communities work for money, or do they work to create daily food? Rosy Barrios: The majority of the people in the communities work in the countryside, growing maize, growing beans, growing coffee. In Motion Magazine: For their family or for the market? Rosy Barrios: Right now it’s for their family, because the market for maize, for coffee, isn’t worth anything. More time is spent working in the fields, and when you take it to market, the other maize is there, which comes in from other countries more cheaply. So they don’t make any profit. What’s going on right now is that they’re working to eat, in order to support themselves on a daily basis. If we work to sell, then we don’t even make enough to eat for one day. Those who plant coffee sell, at the most, a bit of their coffee. But it’s not worth it now with the free trade treaty which came into the Mexican and Chiapaneco markets. (Prices) fell through the floor because maize isn’t worth anything; beans aren’t worth anything, and all that because maize and beans from other countries came in. They’re much cheaper than the ones from here. They don’t make any profits taking their product to market here in the communities, because there’s other maize which is cheaper. The people go for that maize which is cheaper and the maize from the community, the maize which is more natural, the people don’t buy any more. So, the people have opted for planting in order to survive, for their daily sustenance. In Motion Magazine: What is the significance of maize for the people? Rosy Barrios: Maize, the fields, have a very important significance, because maize is life for many people. Maize is part of our lives. It’s as if they respect it like a human being. As if we belong here to one, as if we look like an ear of maize. Especially because history says that Emiliano Zapata was supposedly reborn in the fields. He grew again in the fields of maize, and so the people have attached a lot of importance to maize. Above all, it feeds us. The primary foods here are maize, tortillas, pozol. Maize is consumed very much here, so it’s quite important. In Motion Magazine: Is maize a part of different traditions? Rosy Barrios: I don’t believe maize is a tradition, instead it’s part of our life, because if we didn’t have maize, we wouldn’t survive. It’s part of our food, all that, no? There are different traditions and different customs, but maize is a food almost everywhere in Chiapas. It’s a part of us, which the campesinos have always worked, and now they’re familiar with maize, with the fields. I don’t believe there are different traditions regarding maize like there are with other things like language, the typical clothing, the traditional clothing which is worn, the fiestas. In Motion Magazine: What do you think about the Sexta? (The Sixth Declaration of the EZLN) Rosy Barrios: I think the Sixth Declaration is a very important step, which we should fully support. We should all be part of it because it’s a very important step for the people, for the communities, and, I believe, for the entire world as well. This Sixth Declaration is no longer just for the Mexican State, but for the entire world. What I think about the Sexta is that it’s a plan for making a new struggle, a more peaceful struggle, as they say. Without war now, but, if the government were to respond badly, they are also going to defend themselves. I don’t believe they would allow themselves to die. I think the Sixth Declaration is something we all support, and all together. We’re going to join together and do more. We are going to learn better. While the government is globalizing its power, their ideas, we aren’t globalizing our ideas. We, all together, all the poor of the world, we won’t be globalized, we’ll work against the government. I believe that is the idea of the Sixth Declaration. It says we should learn about the struggles in other countries, learn about the different struggles right here in Mexico. I believe it’s important because united we are going to be stronger. United we’ll have more strength for defeating the powers that humiliate us. But if we work with one organization here, one organization there, and never unite, we’ll always be like this. So it’s important that they want to learn about other struggles. The new Mexican constitution is quite important because that could recognize the San Andrés Accords, because it’s an indigenous community law which many people, which many states where indigenous exist, haven’t recognized. The Sixth Declaration is an important step which the EZLN is taking in its work. It’s an important step, which I believe many of us are going to support. I don’t believe that we are going to be left alone. In Motion Magazine: What would you like to see in the future here in Chiapas? Rosy Barrios: What I’d like to see in the future would not be just in Chiapas, but in all of Mexico and even in other countries, because there are other countries which are suffering the same or worse than we are. That we be respected. That we be recognized as indigenous. That we have our own rights in the community. That the government doesn’t come in and manage us, manipulate us. That we have our own work, economically, that we have work ourselves, without having to depend on the United States, which is a country which has tried to exclude us. It’s a government which has tried to exterminate us. I believe that what we hope for the future is for a new constitution, which would be a very important advance these days. But, if the rights of the indigenous peoples were to be recognized, that would be the most fundamental. So we can begin working to rebuild ourselves. So we can begin to be heard. So we can begin working together and be respected. Published in In Motion Magazine December 18, 2005 Also see:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you have any thoughts on this or would like to contribute to an ongoing discussion in the  What is New? || Affirmative Action || Art Changes || Autonomy: Chiapas - California || Community Images || Education Rights || E-mail, Opinions and Discussion || En español || Essays from Ireland || Global Eyes || Healthcare || Human Rights/Civil Rights || Piri Thomas || Photo of the Week || QA: Interviews || Region || Rural America || Search || Donate || To be notified of new articles || Survey || In Motion Magazine's Store || In Motion Magazine Staff || In Unity Book of Photos || Links Around The World NPC Productions Copyright © 1995-2018 NPC Productions as a compilation. All Rights Reserved. |