|

Interview with Juana Benavides

Sustainable Development in Bolivia

"Not Sustainable If It Doesn't Mean Income For The Families”

The Management of Vicuña

On the road to Sajama National Park

Oruro Department, Bolivia

|

|

|

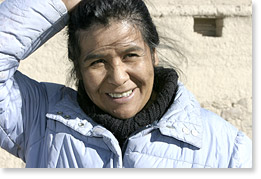

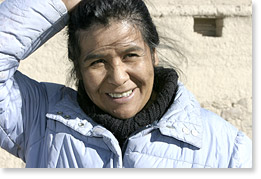

Juana Benavides in Caripe at the foot of Mount Sajama. (It was a windy day.). All photos by Nic Paget-Clarke.

|

|

|

|

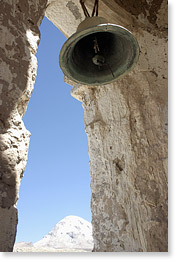

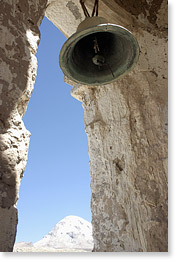

The 17th century church Comarapi Virgen Rosario and Mount Sajama in Caripe (altitude 15,000 feet).

|

|

|

|

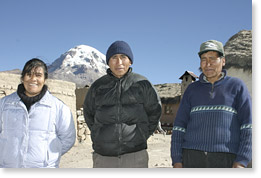

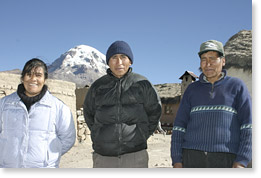

Juana Benavides with two members of the Sajama Association of Camelido Producers -- Felipe Huarachi y Julian Crispin.

|

|

|

|

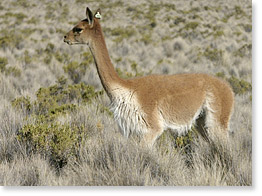

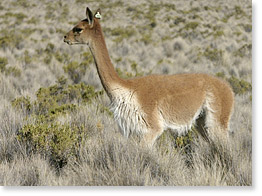

A vicuña near Mount Sajama.

|

|

|

|

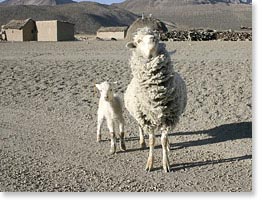

Caripe alpacas.(Click here to see a larger version.)

|

|

|

|

The bell tower of the Comarapi Virgen Rosario church. (Click here to see a larger version.)

|

|

|

|

Mount Sajama.

|

|

More photos. |

Juana Benavides works in family-farmer and indigenous communities in Bolivia assisting in sustainable development programs. This interview was conducted (and edited) by Nic Paget-Clarke for In Motion Magazine on September 10, 2006 on the Altiplano in Oruro department on the way to the Caripe community at the base of Mount Sajama. The interview was conducted in Spanish and simultaneously interpreted by Bernarda Zellez with additional translation later by Nic Paget-Clarke and irlandesa.

Sustainable development in Bolivia

Juana Benavides: My name is Juana Benavides. I am going to talk to you about my experience with the Sajama Association of Camelido Producers in the Curahuara de Carangas municipality in Sajama province, Oruro department. (Editor: camelidos include llamas, alpacas, and vicuñas.)

In Motion Magazine: Could you please talk about your other work on sustainable development in Bolivia?

Juana Benavides: I have worked a lot with economics-based family-farmer organizations. I work to strengthen their organizational structure. Afterwards I work with them on how their system of getting their products to market must develop in order to achieve sustainability.

I have worked a lot in the Yungas region with coffee producers associations, with women's organizations who are working to develop their products in order to create added value. Also, it has been my responsibility to work with indigenous people in eastern Bolivia strengthening the quality of their production.

Perhaps one of the most important, most successful of these activities in my life was having worked with camelido, alpaca producers. Now, they are also developing tourism.

The community project that we are going to visit began in October 1998. It comes from replicating an experience that was developed in Ulla Ulla in the northern part of the Altiplano in the La Paz department. It's very much concerned with strengthening the herders' organizations so they can achieve a higher quality of production.

An organization of producers

We began the project in Sajama with the goal of storing and purchasing the camelido herders' wool. As a first step in the process of change, the women have a source of employment classifying the wool. We work with the association so that they have a legally established structure, recognized by the government. In that regard we have managed to achieve the recognition of the association as a legal entity, as an organization of producers.

There has been a lot of work with the organization on the issue of management, training in administrative management. It has allowed them to acquire a fund, money so they can store and buy their members' wool. That is why it was very important for the organization to know how to manage their income in a transparent manner and for the community to have its own control system. There have been a lot of experiences in similar organizations in Bolivia where they didn't work on issues of administrative management and accounting, and very often these organizations failed.

On the one hand, we worked on these administrative issues, and on the other we worked to transfer to the community technological knowledge. In regards to the transfer of technology, we began with improving the technique of shearing the animal, removing the wool. That's where we begin the quality control process, with the shearing.

Then we began training in the classification of wool according to international standards. This process has been principally directed by the women. Why? Because it requires a lot of touch, sensitivity in touch, to know how to classify by color and quality. For example, with alpaca wool, and also with vicuña wool, which is much finer, it is necessary to classify into four categories. For example, we call the highest quality alpaca wool "baby" alpaca. Wool at this level of quality ranges from 19 to 21 microns in thickness. The second quality, which is Super Fine, goes from 21.5 to 25 microns. Each wool quality type has a thickness range. It is a good system (for the alpaca wool) but the classification with the vicuña wool is not as demanding.

Next, we worked on the processing of the wool into very high quality thread. This was why and how the organization alone became able to sell the thread. The women are also making scarves and shawls. This process is still functioning, at this time, in the community. They are still doing the storing (of the wool), the classifying, and the making of the finished products, the garments.

What is interesting now is that this same community, this same organization has entered into a new type of activity, which is tourism. They are still producing alpaca, but they are also engaging in tourism. We are going to visit a hotel that they have in the community, which they themselves are administering quite well.

The management of vicuña

And now as a new initiative, which is being promoted by the government, is the management of vicuña.

In this area, though, the vicuña cannot be exploited because it is categorized as an endangered species. To be able to use the vicuña, the community must organize itself, and afterwards corral them, cut off their wool, classify the wool. But they still cannot sell it because national regulations do not allow it. At the international level there is CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (http://www.cites.org) and a program has been implemented in these areas, and others, for the protection of the vicuña. This allows us to shear the wool of the vicuña but not to kill them.

Why have these communities become involved with the vicuña? Because the vicuña have increased their numbers in this area, and now they are competing with the alpacas for food. Furthermore, there is a lot of clandestine hunting of this animal in this area because vicuña wool brings a very, very high price on the black market (the informal economy). For example, a pound of alpaca wool costs a maximum of 25 bolivianos. In contrast, a pound of vicuña wool costs more or less $100. It was not fair for the communities to have vicuñas who eat the alpaca's food, but not be able to take advantage of the vicuña. Now, according to the rules, because of the number of vicuñas in Sajama National Park, it is OK to take advantage of the vicuña in a certain way, which is to shear the wool and classify it for later going to market.

Again, to be able to do this according to national laws, the people must organize themselves. In this area, each community has organized what is called the Association of Vicuña Managing Communities. This is a requirement of the government. If they don't act in this way they will not be able to take advantage of the vicuña.

In Motion Magazine: Is what they are doing now illegal?

Juana Benavides: What they are doing now is legal.

In Motion Magazine: So when did the law change?

Juana Benavides: The last government decree was January 18, 2005.

A supreme exceptional decree / community pressure

In Motion Magazine: Was that Morales who made the change, or the Congress?

Juana Benavides: Before Evo. It is a supreme decree, not a national law. It is a decree by the former president to normalize things a little, to establish rules as to how to take advantage of the vicuña.

But, we still haven't gone into marketing the vicuna. We are waiting for an exception to the decree allowing us to be able to sell because the current law still considers the vicuña a protected animal, not to be commercialized, nor the wool used (to make products, like sweaters).

In Motion Magazine: So people make these other products in the community?

Juana Benavides: No, that is what I was going to tell you. Right now we don't have the technology to do that in Bolivia. Although, for many years, the vicuña has been used in Bolivia illegally.

Why? Because, for women, for example, it is prestigious to have vicuña clothing. Why? Because according to the rules the wool must be manufactured in a thread workshop and afterwards made up into a product of high quality. For example, a man's jacket can easily cost $10,000. So, in order to be able to sell the wool that the communities have (successfully) collected, which they have been able to get from the vicuna, they are at this moment waiting for a supreme exceptional decree allowing them to sell the wool.

In Motion Magazine: And do you think that is going to happen?

Juana Benavides: I think so. I think so because many communities have begun to pressure the government to make it happen.

In Motion Magazine: What is your opinion, weighing both the protection of the animal and the need for the community to make a living, of how the two come together?

Juana Benavides: As for what the government is doing, it is implementing a vicuña monitoring system, as it is called, but it is organized by the community.

There is also this entire system of vigilance because, as I was telling you, vicuña wool has a high value and must be protected by the Bolivian state. If this vigilance is not implemented the number of vicuña will decrease. Before, what happened was, the people exploiting the vicuña wool would kill the animal.

|

|

|

The market in the Andean community of Curahuara de Carangas, Oruro department, near the border with Chile. The market is held twice a month.

|

|

|

|

Selling llama and alpaca wool as fleece and as balls of wool.

|

|

|

|

Wool and fleece.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Llamas in the market.

|

|

|

|

In the market.

|

|

|

|

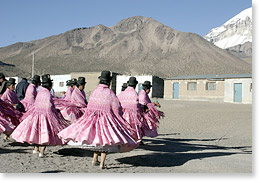

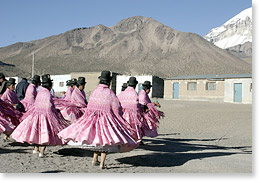

Dancing during a religious festival in the small mountain community of Sajama, by the snow-covered Mount Sajama. (Click here to see a larger version.)

|

|

|

|

Another photo of the religious festival dance.

|

|

|

|

Another photo of the religious festival procession.

|

|

|

|

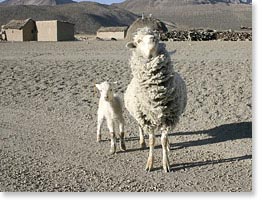

A sheep and a lamb on the Altiplano between Mount Sajama and Chlean border.

|

|

|

|

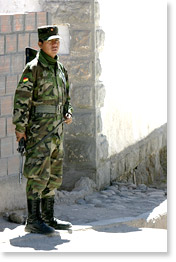

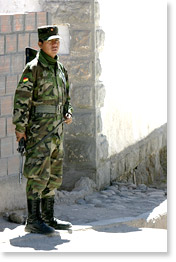

A soldier on guard at an entrance to a military zone near the border. |

|

|

An Andean agreement

In Motion Magazine: So this is a way of both protecting the animal and providing some income to the community?

Juana Benavides: Yes.

In Motion Magazine: Who came up with this idea?

Juana Benavides: Well, the worst thing is that before it was not the community that was taking advantage of the vicuña. There were other people who came from outside, killed the vicuña, and took away the wool. So, after this law (decree), in which they speak of organizing these communities, these vicuña managers, they initiated this process themselves, organizing the communities to make these shearing campaigns, and so, well enough, we are waiting for the law to be able to sell.

This process has been going on since 1928, more or less -- also, it is a regional process because the vicuña is a wild animal. In that year there was the first count of how many animals (vicuña) there were in Latin America. And, from that time on, we could see how the number had been decreasing. For example, in all of Bolivia we had only about 3,000 animals. The same was true in Peru, Chile, and Argentina. And, in 1948, an Andean agreement was signed to protect the animal.

At that moment, a system of protection was started and, in the last census that was done of the vicuñas, there were about 60,000 animals in the entire country. But, even though the number of animals has increased, another problem began because the vicuña became a pest for the communities. Why? because they share the same territory as the alpaca and llama. They begin to eat the same food as these animals, and that makes it a negative for the community.

The communities and the government, with the support of the World Foundation for the Environment, are undertaking a development strategy to take advantage of the wool so that the people themselves will become aware that this resource can provide families with a better income. And, as a first step, the state sought authorization from CITES (the International Convention for the Protection of Endangered Species), presenting itself to CITES. Why? So we could make use of this resource without eliminating it, as was usually happening before.

Chaccu

A pilot project was created, a small program in the Ulla Ulla region in the north of La Paz (the department of La Paz) where a "chaccu," as it is called, was done. The word means a sleeve (or chute) which is made by all the communities so the vicuñas will go into this kind of corral. Once the vicuña are in this corral, the shearing is done, the cutting off of the wool. A record is made of the animals to see how much they weigh and how much wool is obtained from each animal. Also, they receive medications, vaccinations. In that first project, a volume of wool was obtained that could now be sold outside.

Then, since they saw this was a very interesting experience, which energized all the communities, the families within the communities began talking about replicating it in other areas, -- and that is how we came to Sajama. But to be able to accomplish this, with the laws, we had to organize the associations, the communities, so that they would form their association and develop a structure for the shearing, for the "chaccu". Now we are in the stage of looking for the law to be able to sell what has been collected in Sajama.

And that is the experience with the vicuñas.

... if it doesn't mean income for the families

In Motion Magazine: What does sustainable development mean in this context?

Juana Benavides: One thing that I have learned during this time is that if you want to protect natural resources where there are people living, if this natural resource doesn't involve income for food, it's of no use.

That is something that I learned not only here in Sajama but also in the forests of Amazonia. Protection is difficult when there are people living in an area. It is not "sustainable" simply to take care because an animal is very beautiful, because a plant is very pretty, if it doesn't mean income for the families.

Facing inequality

In Motion Magazine: Did you want to talk about the situation for women that you have seen in your work?

Juana Benavides: A very interesting process that occurred in Sajama is that before we began to work in Sajama the women always sat in the back during a meeting. Generally, they don't speak in a meeting, they don't participate, and if they are invited it is to prepare food -- but never to participate in decisions that must be made in the community.

Generally, these communities have the highest levels of poverty and the men leave the communities, they migrate, a lot, to Chile, to the cities. They go in search of income. So, what happens with the women is that they have to assume all the duties for the alpaca production, for the llamas, but also family responsibilities. This represents an excess of work. Women in this area can easily work fifteen, sixteen hours a day.

Another issue is the violence. There is a lot of violence in the communities. They wrongly say that the violence towards women is cultural, but that is not so. They often say that violence towards women is cultural, that it is customary for a man to hit his wife, but it is not.

Also, the level of illiteracy among women in these communities is very high. The fact that women participate very little in the decisions in these communities is widespread. For example, how is this seen? In the communities those who speak less Spanish are the women, because you learn Spanish in school. And, (related to this), another situation which you see a lot of in the communities is that the man eats more. The man has more opportunities to go to school. This makes it so that the women are out of balance, facing inequality when facing the same conditions as the men.

A strategy for survival

In Motion Magazine: Do you want to talk about people's creativity in developing ways of making a living?

Juana Benavides: The families have a strategy for survival. The primary economic activity is the camelidos - the alpacas and llamas. The second activity is migration. Generally, during certain times of the year, they go to work in agriculture, or they go to the cities to work in construction and afterwards they return to the community with money.

But one dynamic that has changed a lot in Sajama is that, in addition to working with the camelidos, people now work in tourism, in artisan work, with vicuña, so now people, especially the young people, don't have to go away.

In Motion Magazine: The young people are staying in the communities?

Juana Benavides: Yes. We are going to visit a hotel, which this community manages, and you are going to see that the majority of the people working there are young people. Before, this wasn't so because the young people tended to leave, principally to work in Chile.

Eco-tourism

In Motion Magazine: Can you talk about eco-tourism?

Juana Benavides: They have received a lot of support from a German corporation (Germany-based GTZ consults with the MAPZA / Management of Protected Areas and their Peripheral Zones project as part of Bolivia's SERNAP / Servicio Nacional de Áreas Protegidas.). They have constructed a lodge, a tourist lodge with all the right conditions so they can receive tourists. A community enterprise has been set up which deals with administrative issues for all aspects of the hotel. Various groups of young people have been trained to prepare food. They have also been trained to be guides for the tourists. They have been trained in administration and accountancy. They have met with various travel agencies so now they can sell packages to visit all of Sajama National Park and sleep in the hotel. This park is visited a lot by tourists climbing Mount Sajama.

So, the Caripe community, which is the name of this community, has the hotel, and then you can climb to 5,700 meters where there is a small hut, and then go on to ascend the mountain. There has been a lot of success with this initiative, and now the community has constructed more rooms for more tourists.

Published in In Motion Magazine May 16, 2007

Also see:

- Entrevista con Juana Benavides (en español)

- Interview with Bertha Blanco of Bartolina Sisa

National Federation of Campesina Women of Bolivia /

IPSP Department / For the Sovereignty of the Peoples

Part 1: Defense of the Peoples

Part 2: The History of Our Ancestors /

Time to Take Responsibility for Political Decisions

La Paz, Bolivia

- Interview with Miguel Angel Nuñez

Farmers are Demanding Agroecology:

Making Democracy Participative

Barinas and Caracas, Venezuela

- Interview with Severine Macedo

Youth Representative of FETRAF-SUL

Independent Alternatives for Rural Youth

Chapecó, Santa Catarina, Brazil

- Interview with L. A. Samy and Christina Samy of AREDS and SWATE

Association of Rural Education and Development Service /

Society of Women in Action for Total Empowerment)

The poor have to be united / You create alternatives

Renganathapuram, Tamil Nadu, India

- Interview with Gustavo Esteva

The Society of the Different

1 The Center of the World

2 We Are People of Corn

3 Regenerating Community

Oaxaca, Oaxaca, Mexico

- Interview with Peter Rosset

of CECCAM and Land Research Action Network

Agrarian Reform, Land Reform, Food Sovereignty

San Felipe, Yaracuy, Venezuela

- Interview with Geraldo Fontes of the MST

The Landless Rural Workers' Movement

“Without depending on power or having to take power”

Part 1 -- Building the New Society Now

Part 2 -- Agrarian Reform / Agribusiness

São Paulo, Brazil

|