Global Eyes

The Women’s March, during the rain. 40,000 march in San Diego, California, January 21, 2017. More than a million marched throughout the U.S and internationally against the rhetoric and threatened policies of the newly inaugurated President Trump. Photo by Nic Paget-Clarke.

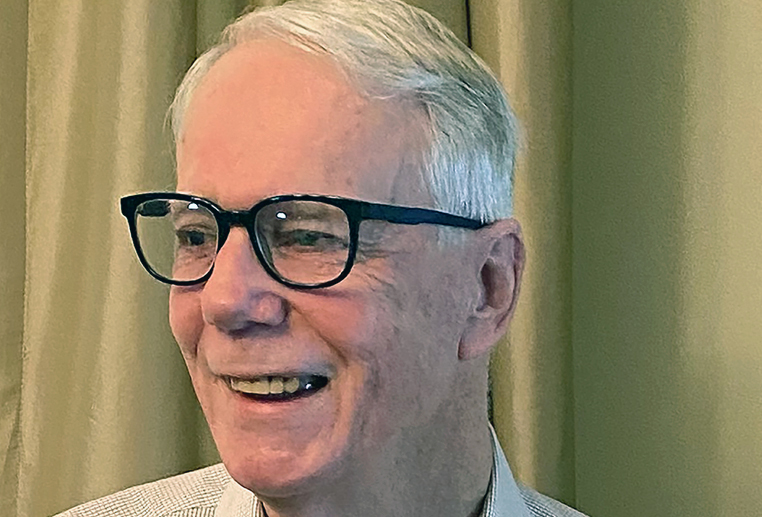

Patrick Manning is, “a professor of world history at the University of Pittsburgh, Emeritus. I retired eight years ago but I’m still holding on to the title and the connections to the World History Center, which I founded there in 2008.” He is also a past president of the American Historical Association.

January 19, 2024

Interview with Patrick Manning

“The Evolution of the Human System”

Language, Migration, Social Institutions, and Outpourings of Public Sentiment

This interview of Professor Patrick Manning was conducted (and later edited) by Nic Paget-Clarke for In Motion Magazine on January 19, 2024. With follow-up correspondence, further clarification was added to the interview. The interview was conducted through the web on audio/video software with Patrick Manning in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Nic Paget-Clarke in San Diego, California. The interview was inspired by three of Dr. Manning’s books: “Migration in World History; “Songs of Democracy: The World, 1989-1991”; and, in particular, “A History of Humanity.” Download a PDF of the interview.

The Link Between the Social Side of Human Life and the Biological Side

In Motion Magazine: What was the process, or what were the experiences, which led you to realize that history needs to be re-organized away from an often national perspective to a global perspective?

Patrick Manning: When you put it at that breadth, I would say I realized it by my undergraduate times when I was moving from initial studies in chemistry and biology into history, and into African history where it was clear that the study of African nations needed an understanding both of the colonial context, that is to say, European conquerors, and the global connection of decolonization at the time.

But having that initial insight still left me to go through thirty years of doing African history, mostly in national terms. And so, by stages I’ve come to see more and more the importance and the particular ways of trying to study history without losing track of communities and nations, but nonetheless keeping track of global patterns as well.

So, for this particular book – A History of Humanity is what it ended up being called – it’s an attempt to connect the social side of human life to the biological side of human life. To argue that that particular connection has been neglected a lot and that learning how to link the two together is going to give us insights about both the social and biological side of it.

So, about 2014 or 15, just as I was retiring, the focus on this way of looking at things developed fairly sharply in my own mind.

Fongbe

In Motion Magazine: I’ve noticed that in your early years of study, you lived in what was Dahomey, and is now Benin. Would you like to talk about that experience?

Patrick Manning: Yes. So, I had four months of living in Porto Novo, the capital of Dahomey, as it was then, but I got to know some particularly strong scholars there and some interesting leaders in the old monarchy, and the international community of the area. I got to look at society around me. I would say I enjoyed it. I enjoyed having to struggle to learn my French and a few words of Fon. I didn’t get very far with the latter. But it gave me a base that I’ve relied on ever since then.

I’ve been back about four or five times. Amongst the things you see, for example, (is) that people are immensely more healthy nowadays than they were then. It is not that the place is necessarily richer, but nonetheless there’s dramatic changes in urban life, and I think in rural life as well.

In Motion Magazine: And the language that you mention?

Patrick Manning: Fon. Fon is the language of the principal ethnic group. The language is called Fongbe. And the term “Gbe” is used for the language of a much larger region, including southern Benin, southern Togo, parts of Ghana. Maybe five, six million people, nowadays, speaking dialects of that language.

A Systemic Approach

In Motion Magazine: The subtitle of your A History of Humanity book is The Evolution of the Human System which brings to mind Charles Darwin’s scientific approach – in fact, you talk quite a lot about how your analysis of history has many analogous processes to those Darwin used in his thesis. Can you talk about that?

Patrick Manning: Yes, I can. The book title principally was, The Human System. That’s where I began, but Cambridge University Press didn’t want to do it that way. They wanted to call it, History of Humanity, thinking that was a more unique title. In fact, there were three of four books already out with that title on it. So, it didn’t sell well. Nonetheless, it has enabled me to have other conversations such as this one.

But the notion of a human system is to take a systemic approach. Systems theory has been more and more developed in the last century as a way of thinking about an overall multi-dimensional structure that works through interactions, and inputs and outputs, and transforms things over time. I wanted to talk about all of human society in systemic terms and talk about the way in which the system has changed.

A footnote to it is I had chapters in the book that explained the evolutionary thinking from the nineteenth to twentieth century and the editors wanted that taken out. So, we took it out and I put it in another book, Methods for Human History, which includes 36 different historical methods for graduate students and undergraduate students to explore, and several big chapters on the development of the academic system, especially, about the changing of evolutionary thinking, not just in biology but also in physics, which got so much attention as the leading academic discipline. And then in social sciences as well.

The particular point with Darwin was that his vision of evolution included a specific mechanism. It wasn’t as specific as it is now, but it was the idea of natural selection involved particular sorts of changes that would take place in the forms of animals according to which variations they were born with and how those variations survived in a changing environment.

And the contrasting philosophy at that time was one which just said, ‘Well, evolution is just change, everything changes.’ And that vague sort of macro-level assumption, that everything just changes and it all works out somehow, has really dominated the historical literature for a long time. Historians have been slow to try and come up with specific theories. So, Darwin is my example of someone who started a specific theory and where his followers made it more specific, and, as a result, biology has immense strength in so many different areas, as opposed to vague generalizations. That was the task I set myself – to make those sorts of connections.

In Motion Magazine: And did.

Patrick Manning: A start, in any case. Since I finished the book, I’ve gone beyond many of the points in there and been able to develop further thoughts on them.

Language and Network Theory

In Motion Magazine: Do you want to give an example?

Patrick Manning: Two examples. One is language. I developed fairly fully in the book a theory for how spoken language developed especially out of the community activities of young adults, really children, juveniles – those who are most skilled at language, even today. How that creation of the social interactions amongst groups of people added the essential element, along with years of study by the individuals, as they invented and learned languages. That’s what got the grunts and gestures of earlier communication into syntactic languages with complete sentences, and enough detail in them that people could really learn from each other. So, I wrote up an article that took three years to come out. But nonetheless, that one’s out.

And another one that I’ve just finished is to take network theory – where there’s been a dramatic advance in the way in which networks are theorized in the last 25 years – trying to take that formal way of thinking about networks and apply it to early human social structures. So, thinking of a household as a network, and then a community of, say, 150 people as a network, and then watching the ways in which after some thousands of years of speaking, communities, they suddenly began to get larger into things that I’ve called ethnic groups and societies, using common terms, but, on the other hand, to link them to particular structures of networks that are built up of smaller networks.

So, those are two examples.

Languages to Trace the Movements of People

In Motion Magazine: In the Human System book, you focus on several specific threads in the history of humanity. For example, the invention of spoken syntactic language, the role of migration, and the development of social institutions. They all evolved from the beginning of our history. Could you explain why you focused on those three in particular?

Patrick Manning: Right, so migration I haven’t mentioned yet, and yet it was the first area that I focused on.

In the 1990s, I had the good fortune to get a substantial grant from the Annenberg CPB (Corporation for Public Broadcasting) to create a CD-ROM on migration in modern world history. And we made such a thing and completed it in 2000, just as CD-ROMs were dying out. It didn’t get very widely circulated. But a lot of graduate students and I did work on it that assembled a wide range of issues in migration – thinking of the changes that are brought through migration in history.

Then, I had an opportunity to write a short book, in a series of world history books, on migration in world history. And that book I took all the way back to the beginning of speaking. In 2005, when that book came out, was when I first articulated the idea of languages spreading from Africa, 60-70,000 years ago, to the rest of the world and using the distributions of languages to trace the movements of people. It’s really interesting how little language evidence is used by people who are tracing long-term history of humans.

In any case, I had also done a lot of work on the Atlantic slave trade, tracing the demography of people as they are captured and sent over to the Americas, or sent to other parts of Africa, or indeed to North Africa and to Asia. And that required me to learn demography, or learn enough demography, to get past the vague generalizations to things that gave particular attention to the difference between the male and female side of enslavement.

That’s a way that I was able to demonstrate that African populations, at least on the west side of the continent, really did decline in the 18th and 19th century. Even though more males than females went across the Atlantic, there were enough young females who left that their capacity to give birth to children was put to work in the Americas rather than in Africa. And for shortage of new children, the population (in Africa) declined until late in the 19th century.

So, migration gave me a lot of things to work on. And now, as I’ve got to a longer-term view, I’m changing and extending my ideas on migration, starting to ask about the very earliest human migrations before we were really humans. Asking, were they particularly human-like or were they like just other animal migrations?

Changes in Patriarchy at the Community Level

In Motion Magazine: Following up on migration, and looking at the article that you published in your January newsletter on the Frontiers of Family Life around the Atlantic Ocean and the Indian Ocean, it is possible to see how the three themes I observed in your book — language, migration, and social institutions – they intertwine. You talk about out-migration and in-migration, the changes in family size, in patriarchy. So, I have a couple of questions.

One, on the history of patriarchy. It’s still very strong throughout the world, but in this article, you describe a specific change in this form of governance. You talk about decentralization and smaller families. And it just made me think that, given the time you’re describing is the spread of commodity-based slavery and the beginnings of various colonial empires, did it lay the basis for what came after it?

Patrick Manning: Well, the study of patriarchy is so interesting, and it’s now studied in so many different time periods, in so many different ways. And all of those are relevant. But you picked this area of the expansion of empires – in the expansion of capitalist plantations in the empires – to focus on. So yes, what I was able to see, partly in the article you mentioned, partly elsewhere, is that the interactions of the triangular trade, that is to say the European, the American, and the African side of it, enabled three different types of patriarchy to develop.

In Africa, more males than females were sent out of the continent. And the result was there was a shortage of males. Those males who survived still had access to the larger numbers of women who survived. So that developed, you don’t want to call it polygamy because it wasn’t necessarily marriage, so marriage institutions suffered in Africa at this time. But the number of women under male control, under any individual male control increased, and the children of the women typically did not belong to them, but belonged to the father. That’s one sort of patriarchy.

There’s another sort of patriarchy in Europe, in that the men who run the shipping companies that are either sending the materials to Africa, or shipping people over to the Americas, or shipping the products back to Europe, this is a male-dominated economic system that grows.

And on the American side, and the plantation side, you have all along the Atlantic shore from New York down to Argentina, lands owned by white males, with mostly black males doing the work and with smaller numbers of white females, and especially black females. But in any case, the owners of the plantations again had access either through marriage or informal relations with the women, white and black. And that created yet a third sort of social structures of patriarchy that go with that particular time.

So, there’s the model I set for it. And one can, you know, play with it in lots of details, but it’s an example of how doing these studies at the community level gives you insights that might not show up just looking at aggregate figures.

Patriarchy and Male Dominance Spread Widely

(Editor’s note: this section added in later correspondence) But there are other dimensions that need to be added. One begins with patriarchy and male dominance among Indo-European speakers that spread widely from 5,000 years ago – to Anatolia, Iran, North India, and west to Europe. Formal marriage was monogamous, but powerful men had extra women. A second form of patriarchy arose among Semitic speakers of the Levant and Arabia. (Their languages developed from Afroasiatic languages of northeast Africa, but patriarchy was not important on the African side.) Semitic patriarchy allowed formal polygyny, especially through cross-cousin marriage. This form of patriarchy spread with the Judaic religion from the first millennium BCE, and spread much further with the spread of Islam during the late first millennium and second millennium CE. Traditions of polygyny and male ownership of property spread across North Africa, into Central Asia, and to Iran and South Asia.

The worldwide expansion of Europeans from the 15th century spread European (that is inherited Indo-European) traditions of patriarchy to many regions, especially through spread and imposition of Christianity. Initially, it was an ideological spread of patriarchy. But with the slave trade (across the Atlantic and elsewhere), the surpluses and shortages of females created different sorts of patriarchy among Africans overseas and on the home continent. As Islam and Christianity spread further across Africa, those two or more types of patriarchy were imposed increasingly on Africa. Such imposition came right up to the 20th century, where European colonial powers removed women from legal and social influence in many African societies.

This story of patriarchy throws into relief the global task of feminism: to challenge the various forms of patriarchy and anti-female discrimination. Even if the various feminist movements arose in specific national, religious, or cultural traditions, it seems clear that there is a basic reason for them to combine and work together to enable more women to develop to their full potential rather than undergo domination and neglect.

Migration and Diasporas

In Motion Magazine: Oh, that’s very interesting. So, the other thing I mentioned in the email I sent you was the whole idea of the diasporas. And not just the way it’s used now, but more the idea of whole peoples moving around many parts of the globe. So, I was wondering, in sheer numbers, in percentages, how do migrations today compare with migrations of the Holocene era that you described in the book?

If we were to ignore the borders that are planted upon us today, would the numbers of actual in-motion diasporas migrating around the planet present a map, similar to what we have now? And do you think that with global climate change, we’re in the midst of a major realignment of people? Because, as Mr. Trump will tell you, it’s the main battleground for a lot of the reactionary politics all over the globe.

Patrick Manning: So, comparing this to Holocene-era migrations, meaning, by then especially, agricultural peoples moving back and forth; and then, one could also think of the earlier Pleistocene migrations, where smaller populations were settling Europe and Asia and the Americas, that’s another comparison. But an example of the Holocene migration is Indo-European-speaking people coming to India and Iran and all of Europe, and so forth, and bringing a specifically patriarchal family system that arguably remains. To compare that wave of migrations with the wave of migrations today is what I understand you to be suggesting. And I think it’s a great comparison to make. I don’t know any place where it’s really been made. But let me see what I can do with it.

The earlier migrations were by sea as well as by land, it’s worth pointing out. And we don’t have much documentation of it, but we can derive it and see that there is sea migration in earlier and later times.

In later times, the migration of Africans was the largest migration that had ever taken place up until 1850. And after 1850, the African migration continued, but the migration both from Europe and from Asia, meaning India and China especially, expanded to a rate that then greatly outpaced the African migration.

So, the term diaspora didn’t really come into use until the 1960s. Of course, it’s a term that comes out of the Jewish experience and goes way back for that reason, but it got generalized first for the African diaspora, and then for Chinese and Indian and Japanese and Portuguese, and so forth diasporas thereafter. So, where I’m going to try to go with this is to talk about, on one hand, multiculturalism, and on the other hand, population sizes, because these two things lead you in different directions.

(Editor’s note: this paragraph added in later correspondence) Migrants have long been labeled, often informally, by their ancestry. In the era of modern nations, migrants and people of migrant ancestry may choose to form diasporas – communities with a common identity based on their place of origin. Diasporas are social and cultural communities that stretch across national boundaries. One may be a member of more than one level of diaspora: thus, a single individual may adopt Zapotec, Oaxaca, or Mexican diaspora identity, or may participate in Zapotec and Mixtec diasporas through past intermarriage. Diasporas do not have governments or armies, but they may have political positions and seek to advance the welfare of their community. In the widespread migration and electronic communication of today, many diasporas exist and communicate. They are an important aspect of global culture.

Multiculturalism

Multiculturalism is a term that, you know, came more out of North America than anyplace else, maybe out of Canada, particularly. It’s clearly a result of migration. And it refers to the idea that the various different cultural ancestries figure out ways to get along with one another. Or it can be seen as a threat. But I think it’s a really useful term. And I think it’s a useful term to talk about what’s happening all over.

So, for instance, in the Middle East nowadays there’s an ethnic war going on, which is, in one sense, Arabs versus Jews. And, so, then, the Jews are the migrating population or the returning population. But that’s not enough. Throughout the Arab countries, there are so many people from India and Nepal and Philippines and many other places, that those societies, regardless of who’s a citizen or not, are just as complex in their multicultural nature as the U.S.

The U.S. and Canada and Australia are relatively unusual in having fairly large numbers of migrants into the country. Not so much in European Europe, Europeans are still pretty good at keeping the migrants out. Germans have rules that people of Turkish ancestry, no matter how many generations they’ve been there, they can’t qualify for German citizenship. It’s really crazy, and yet that rule is still followed there. And France has rules that are different in another crazy way. And then countries like Japan and Korea are just beginning to have large numbers of people from say, Vietnam, or Laos, in their populations, and it’s leading to tensions that we’re used to in the U.S. over a longer period of time.

I’m not going to try to deal especially with Trump and his fear of current immigration except to say that that phenomenon is a worldwide phenomenon.

Turkey is a country that has the largest number of people who’ve managed to get into the country and are trying to move on to other places. There’s a great amount of domestic stress because of that.

Population Sizes

But let me talk about population overall. The African population has grown at the rate of two and a half percent, from 1950s ’til now. So, African population is, for the African continent, is far bigger than the population of India, far bigger than the population of China. And it continues to grow.

Meanwhile, most of Europe and most of Asia, population growth is slowing greatly so that there’ll be a real shortage of young people in a lot of countries. For the U.S., because we still have a fair number of immigrants, that shortage of young people won’t be as serious. And the growth in population still continues. We have a growing population, our population is growing quite a bit more rapidly than China, at the present.

But talking to my audience of people interested in African Studies, I want to say that this puts great pressure on Africans to migrate. It depends on what life is like in Africa. We don’t know whether the environmental change in Africa will mean that the progress they’ve made in feeding themselves will end or whether, on the other hand, the progress that they’ve made in educating themselves will continue so that there’ll be skilled African workers ready to go every place. But if you go a couple of generations from now, you can be sure that there will be large numbers of African migrants in China, in Russia, in Japan. We’ve already got the start of a new wave of African migrants here.

Okay, so does that mean war in cultural crisis? Or does that mean it’s just more multiculturalism and people figure out how to get along with it? There’s arguments for each. But we can make pretty good predictions about what will happen with population based on work that’s been done in the last century. So these questions can be posed with some specificity.

Technology, Science, Knowledge, and Social Institutions

In Motion Magazine: Technology. On the one hand, so to speak, technology is simply about creating tools that accomplish tasks. But on the other hand, it seems to come in waves which bring about qualitative changes – changes which, in a strange way, are remembered more than the technology discoveries themselves.

For example, you talk about the discovery of figuring out how to heat metals to thousands of degrees. And from that came iron tools, aiding the changes in everything from conflict to food production. Likewise, the development of sophisticated ships and the major role of merchants and migrations, voluntary and enforced. Could you please talk about what you think about technology in the system of human evolution?

Patrick Manning: Thank you. My first response is about science. As to say, I learned over the last decade or two that world historians pay no attention to history of science. But they pay attention to history of technology. But that also means that world history is not a history of human knowledge. It’s just not written up that way. You know, except for simple, linear notations of the steady advance in material technology, or the size increase in states. But that’s not anything about explaining what was happening there.

So, both on the side of technology and (of) science, the people who specialized in world history have been thinking about other things. Now, there are other disciplines where people have put in more imagination. So the state of human knowledge about technology and science is not as bad as what it is within world history as a field.

I have taken to try to focus on history of knowledge in general. And then to break knowledge into specialized knowledge and general knowledge. So, general knowledge is, well, it’s speaking, or it’s simple numeracy. Or, well, we can take the area that you’ve worked on so much which is farming. Is that general knowledge? Or is that specialized knowledge? Well, it’s both. And there’s the sort of work that’s done by people at the level of general knowledge. But then there are certain things about, you know, figuring out the seasons, and the exact timing for planting and harvesting, and so forth, that require specialists. That makes clear that language is a technology. Written language is a technology. And how each of those is developed and passed on is important.

Then, rather than just focus on the technology, I try to focus a lot on institutions. What are the social institutions that create a technology and sustain it? That makes you think of invention as being not so much an individual accomplishment, but a group project, so that the beautiful early paintings that come from 30,000 years ago and more in Europe, and now in Asia as well, should be seen as a result of a workshop. Sure, there’s a genius, there’s a master painter, but it still requires a much broader discussion, just to get the resources to do the painting, but also an audience to discuss and appreciate them.

You mentioned the heating skill with fire that enables metallurgy to begin, and before that enabled ceramics to begin. So, these are stories about social groups. You know, which task is dominantly male, which is dominantly female? And that discussion for early times has been really cut off from the discussion from more recent times about technology, where it’s all put into laboratories.

It’s worth mentioning though that the fields of engineering, they were practical sorts of things. You didn’t get university degrees for engineering for the longest time.

Now, I’m not sure I’ve done much better than to give another long list of technology. But I’m really impressed with the tremendous acceleration of scientific knowledge in so many fields, nowadays. So that tends to make experts that can’t talk to anybody else. But I also think that the level of general knowledge and the sharing of general knowledge has expanded through literacy, especially. Literacy and a whole bunch of different languages.

So, I’ll just leave that one there and then point to one other point that I’ve learned – I’ve had reinforced greatly from looking at your book, “and the echo follows” – (which) is the relationship between farming and democracy. Therefore, the relationship between farming and passing on knowledge. And knowledge just isn’t there, it has to be actively passed on. And it may be passed on through literate fashions or it may be passed through illiterate fashions, but the fact that it’s being passed on is necessary for people to feed themselves. That fundamental factor probably needs a lot more emphasis in our way of looking at the modern world that looks only at the top level of most high-tech parts of our existence.

The End of the Cold War: Outpourings of Public Sentiment

In Motion Magazine: The end of the Cold War. Conflicts and wars have sometimes had permanent effects on society and individual people. For example: the wars which led to the Westphalia Peace Treaties; World War I and the Treaty of Versailles; World War II and the Bretton Woods Conference and various global governance organizations. In a book you wrote called “The Songs of Democracy” you talked about the unleashing of change, much of it from below, which swept the world – China, Russia, many African countries, and most East European countries, at the end of the decades-long Cold War. Could you please talk about that, and why you thought it was necessary to write it and write it from a global perspective?

Patrick Manning: In February of 1989, Nelson Mandela was released from prison in South Africa. He made his way to Boston where I was in March or April, on a worldwide tour. That was a dramatic set of changes with worldwide response. He first traveled all around Africa, and then second, traveled to Europe and America, and then went back home and was president of South Africa by 1994.

Meanwhile, the Tiananmen demonstrations began in April, in 1989. And June 4 of 1989 was the date when they were crushed by the Chinese government and the military.

So, I was really interested in those movements and demonstrations, and I managed to get myself a grant to buy an expensive plane ticket. I traveled around the Atlantic, around the Atlantic in 80 days. I went to Haiti, to Florida, to Brazil, South Africa, Benin, stopping by Congo-Kinshasa and Congo-Brazzaville. Then I went to Europe. I went to Czechoslavakia (editor’s note: what was Czechoslavakia is now known as two countries, Czechia and Slovakia) and Berlin, and France, and then home. That was in 1991.

And wrote a book. Never could get it published, never could get a publisher to show interest in my stories, which were mostly – there was a certain amount of historical and documentary research – but mostly it was just talking about it. I don’t think my interviewing skills reached yours, Nic. But that’s what I was doing, you know, short talks with taxi drivers and academics and whoever else I met. Delightful times and late-night meals in Berlin, East Berlin, as it still was.

And so I saw those as expressions of democracy, as the public rejection of governments restricting people’s ability to go to school, to work in fields that they wanted to work on, and so forth. Long argument along with that with my father, an active trade unionist, and a clear, old leftist. And what he saw out of this set of changes was that the big powers were going to be able to use it as a chance to get even more control.

And so, he was right in that during the course of the 1990s the G-7 formed the World Trade Organization to formally extend free trade – their vision of free trade – to all the big economies. But I was right in that every now and then, since then, there have been huge outpourings of public sentiment. Some of them in the late ’90s – but in particular in 2003. January and February of 2003 in the weeks before the American invasion of Iraq – this was George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq – which was really counter to what the U.N. had in mind, but nonetheless just going ahead with it.

And those great demonstrations are quite forgotten now – there are some articles and so forth that recall them – but the point is, I mean this is what I’m calling multiculturalism. That people in a lot of different nations, and in a lot of different political situations, were nonetheless standing up to make a statement about the human value of abstaining from such a war, or such dramatic abrogation of people’s rights. And then, you know, they didn’t have much they could do beyond that, except express their opinions.

The Largest and Most Broadly-based Such Demonstrations

And now since October 7, since the attacks by Hamas and the endless counterattacks by Israel in Gaza, we have what are very clearly the largest and most broadly-based such demonstrations. And if you look at it through the news media in the U.S., you think that there’s demonstrations in London, and that’s about it. But in fact, the demonstrations are on every continent, more on some continents than others. But nonetheless, while you can’t say that it’s a majority of the world standing out there, it is remarkable how many people have chosen to take the issue of endless bombing in a particular place as one in which they want to make a stand and ask for a change.

So, following that, this is not totally the first time ever, but it’s the strongest such statement, South Africa’s claim that Israel is conducting genocide. A claim they made to the International Court of Justice in the Hague, in the Netherlands, is being seriously considered and Israel felt they had to respond and try to make a counter argument. A narrow and weak counter argument, I have to say, which just amounted to restating their own presumptions. And now we wait to see, and we don’t know.

So, as I see it, there are two ways in which the current struggle can be resolved.

One would be the old way in which the United States would continue picking those it wants to work with. So, Israel, maybe Saudi Arabia, maybe England, maybe Germany, and work with them to decide what should happen in the aftermath of the war and use their military and political power to impose that, regardless of what the rest of the world says.

Or, that the United Nations, which is restricted by the veto – the United States has vetoed in December the resolution that called for a ceasefire. The U.S. vetoed it. Britain abstained. All the other members of the Security Council voted for it. But the Security Council can take no action. But it’s possible that the General Assembly, the 193 members of the U.N., will take new action.

Actually, the General Assembly has been working up to this for the last 50, 60 years as veto after veto have come, in recent years more from the U.S. than from anyone else. (Though) the other big veto issue is Russians vetoing a resolution in the United Nations calling for an end to the war in Ukraine. So, these two current big wars are in the same situation in that the aggressive power, or the funder of the aggressive power, is vetoing action.

But that the United Nations might, through the General Assembly, take a level of action that is stronger than what it has done before. That would depend on the way in which the genocide charge is resolved and whether it’s resolved rapidly or slowly. How would the United Nations resolve the question in Palestine? You can’t tell. It’s new ground. But by now there’s a long experience within the United Nations on working together in various areas.

So you can consider the idea that world politics will be run really primarily by the most powerful nation, exercising its power and bombing whoever it chooses to bomb. … That’s one way. Or the other way would be some sort of argue-it-out within the United Nations. And of course, the U.S. would be part of that – it’d be a really important part of it – but it would no longer be the one that makes all the difference. And you can see that coming.

It’s clear enough what that would be like. That the vision of it won’t go away, I think, after whatever is a solution to the current crisis, in a way in which the vision of it went away after the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Rules of the Game

In Motion Magazine: One thing you often point out, often by way of example, is that similar developments in society take place in more than one area in the world at approximately the same time. For example, the creation of city states and empires, the rise of settler states, and in one very interesting case, at the same time (in the mid-1800s) as the U.S. was having its Civil War, and the Europeans were dealing with the revolutions of 1848, the British were involved in India and China with the Opium Wars. So, conflicts seemingly unrelated but on the same planet, but at different ends of the planet. Are these just coincidences? Why do you think this happens?

Patrick Manning: No, no, in no way is it coincidences.

A lot of people are working on a theory of capitalism and they’re getting away from just asking what happened in England. So, for an example, of what there can be in a bigger broader view of capitalism. There was trade all around the world in the 14th, 15th, 16th centuries, but when there’s trade, there’s trade cycles.

So, there’s an economist Mark Metzler, who’s tracing trade cycles in the China Sea, in the Indian Ocean, in the African Atlantic, in the North Atlantic, and so forth. And the different cycles went in different directions. But as they became connected, they became coordinated, increasingly so. And, so, the ups and downs became more connected and that was not a diffusion of power from Europe. It was the interconnection of developments happening in commerce in a bunch of different regions.

Okay, so that’s not the whole story, but that’s a hint of a type of mechanism that could lead to the development of a capitalistic system that really is worldwide. Places are not left out of the system until some European comes to impose it.

But my vision is, and this is run through a bit in the book, that an alliance of the British and the Dutch in Europe eventually ended up, after the Napoleonic wars, with several powers that were nationalistically interested in their own imperial expansion, but nonetheless agreed on rules of the game for expansion of their system – of what the British called free trade economy – and that the U.S. adopted a similar approach. And that involved excluding all of the people who were not signed up with them.

So, the Japanese, you know, succeeded at getting admitted to the club before the end of the 19th century. But others, such as the Chinese, were not in the club, and those in India were not in the club. In any case, I can put it another way, that the massacres of Indigenous people in Australia, in the western U.S., and Canada — if you compare the Canadian to the American stories of expansion — also in Argentina, and Brazil, and Colombia, I think. But, also, China was expanding in that way into Manchuria at the same time.

Now, this is not at the level of a verified thesis, but the slogan that gets into such trouble nowadays is in Gaza is “From the River to the Sea.” But in “America the Beautiful” we have “From sea to shining sea.” And I imagine being a Native American person trying to get through singing that song. And that’s the particular time, you know, it’s the 1850s to ’70s.

In that case, the elimination of Palestinians is a latter-day 20th century example of clearing the land in a way that seemed to have worked out in so many places, except Indigenous groups are bouncing back in North America and Australia. And in South Africa, they managed to change the regime, not with total success, but nonetheless with a big, big change. So, I do see a global pattern and see the books that I would read if I could get to it to build together that story.

Peter Purdue is a historian who’s now at Yale, he was at MIT, (they) did a detailed documentation from British reports, especially, and also from Chinese reports of the 1839-42 Opium War. It’s astonishing to read through the details of it. Really a lot of people were killed. And that was a turning point for China.

Understanding Group Behavior as a Priority

In Motion Magazine: Could you please talk about the concept you describe in the book, the We-groups and I-groups? I noticed you were saying that We-groups and I-groups have the potential to turn networks, which concerns relations among equals, into hierarchies. And, that social institutions, you said, arose as the principal implementation of group behavior. And, also, you point out that the sociological approach to looking at societies is to rely on individual behavior. What you and anthropologists do is look at, in addition, group behavior.

Patrick Manning: Yeah, that’s a very efficient summary, thank you, of the existing discussion in the anthropological literature — working on small peoples and long ago. This is a term “institution” to refer to social groups and ethnic groups and work groups, and things like that. And speaks of group behavior. It doesn’t theorize it in any depth, but nonetheless it makes that distinction. And sociologists still treat “groups” as simply being composed of “individuals”. There have been various efforts within sociology to think about group behavior, but it always ends up going back to simple individual behavior.

And so, what’s an institution? The dominant vision of institution in the economics business comes from Douglas North. He got a nice Nobel Prize for the notion that an institution is a way of thinking about things. It’s a norm that’s adopted by the society. It’s just a norm adopted by the society. And then, like private property, there, it’s adopted. And then, that tells you how to create organizations that go with it.

So, the organizations aren’t the institutions, only the norm is the institution. There’s no dynamic to it. There’s nothing that makes it change. And there’s nothing that relates it in any way to the individual behavior or the family behavior of people.

So, there are multiple literatures on institutions, multiple literatures on group structures. And, remarkably, none of them – until the work of Raimo Tuomela, a Finnish philosopher – crystallized what I think is a more than adequate summary of the difference between an I-group – where you’re in a group, you’re definitely in a group, but you’re definitely maintaining your own outlook within the group – and a We-group, where people are in a group, but they’ve agreed to be in the group, they’ve been admitted to the group, they’ve adopted the norms of the group, and agreed to act in the interest of the group. Of course, they still have their own mind. And people who are in a We-group of this sort, that’s not their whole life. They might be in other sorts of groups that are either individual or individual-level or group-level phenomena. So, a person nowadays can be in two or three institutions. If you work at the restaurant, that’s one institution, and if you go to school, that’s another institution, and you learn how to navigate distinctions.

But we need and do not have a vision of group behavior that is clear on what that means in terms of networks, and group behavior in terms of what that means for institutions.

Networks are very flexible sorts of structures. You can have a whole system that’s a network. So, we’re going to have a lot of trouble coming up with a proper sort of terminology here. But I think we’ll end up with a view in which an institution has a task. A network doesn’t necessarily have a task, it just has a clear set of links amongst the people who are in it. But an institution that has a task, and then if it has a task, it has to have a way of completing the task. It has to be able to update itself from time to time. The leaders go away and you have to restructure the institution. Institutions are systems, generally, in that they draw on resources from the outside and they produce materials that are either waste, or useful products that get sent on to the next step.

So, for the last 10 years, I’ve been working on sorting out problems of network and institution. I made a little bit of progress. I made a little bit of progress in finding the progress that’s been done by other people. But I think that the distinction between the I-group and the We-group – which is stated quite nicely in this 2013 book (Social Ontology: Collective Intentionality and Group Agents) by Tuomela, the Finnish philosopher – which is sort of understood by other writers, and, also, just neglected by people who don’t yet see group behavior as a priority.

UNESCO: Combining the Natural Sciences and the Social Sciences

In Motion Magazine: Is there anything else you would like to say?

Patrick Manning: I would like to say that my understanding of where social sciences fit in, compared to natural sciences, on whether we get the funding and the social attention to work on the issues that we want to. I mean, the skeptic might think that it’s impossible, that society will never give attention to these issues – and I think that’s not true. I think that once the social issues become serious enough, and they are becoming serious enough this week with regard to genocide, that there will be private funding support, governmental support, to start serious research on them though we’re way behind in research.

And one interesting administrative fact that I like to emphasize is that UNESCO, which has had three sections for its overview of all of academia – natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities and philosophy – decided in 2018 to combine the natural sciences and the social sciences into a single administrative unit, arguing that they’re close enough that it’s better to work with them together. Of course, the social sciences still have their own subgroup and they’re still desperately far behind in funding, but it’s a recognition by a consensus of the top scientific community that the two belong together. I think that’s a good sign.

***