|

|

|

|

Responding to The Crisis Confronting Black Youth:

Providing Support Without Furthering Marginalization

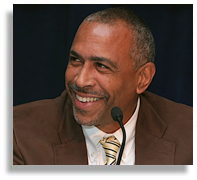

Pedro A. Noguera, Ph.D.

Berkeley, California

Introduction

In recent years, terms such as crisis, at-risk, marginal and endangered, are used with increasing regularity to describe the plight and condition of young Black males (Taylor-Gibbs, 1988; Kunjufu, 1985; Anderson, 1990). The reason such stark and ominous terms are used with reference to Black males is quite clear: a broad array of social and economic indicators point with alarming consistency to the undeniable fact that large numbers of individuals who fall within these two social categories, Black and male, are in deep trouble. Whether the indicators relate to employment or education, health or crime, Black males are consistently clustered toward the end of the spectrum generally regarded as least desirable, and most vulnerable.

As awareness of the acute nature of the problems facing young Black males has grown, an array of innovative educational programs aimed at preventing hardships and addressing the particular needs of Black males have been initiated. These have included various mentoring and job training programs which match youth with adult role models (McPartland and Nettles, 1991); rites of passage programs aimed at socializing and preparing young males for manhood, fatherhood and community responsibility (Watson and Smitherman, 1996); and the creation of all Black, all male schools which have been perhaps the most radical and controversial of all (Leake and Leake, 1992) (1). The common theme underlying each of these initiatives is an assumption that the needs of Black males can best be served through efforts specifically targeted at them, even if it may require isolating them in order to apply the intervention. Often this assumption is combined with the belief that adult Black males are the most appropriate persons to provide the services and support needed by Black male youth (Hale, 1982). Furthermore, it is contended that some form of separation and exclusion from other youth (all other races and ethnic groups, as well as females generally) is necessary in order to maximize the benefits of intervention (Ampim, 1993; Myers, 1988).

Yet, regardless of how benevolent or well-intentioned these efforts may seem, history would suggest that great risks are involved with advocating and promoting separate treatment for African Americans, whether they be male or female. Slavery and Jim Crow segregation were rationalized and sustained by the notion that Blacks should be separated and accorded different treatment from the rest of the population because of their racial inferiority (Fogel, 1989; Franklin and Moss, 1988). In more recent times, there has been growing awareness that special education programs and schools specifically designed for dealing with troubled youth often target Black males because of persistent prejudice, assumptions of innate inferiority, and deeply ingrained fear and hostility (Milofsky, 1974; Wilson, 1992). Rather than helping those served, such interventions have frequently been criticized for stigmatizing Black youth and depriving them of access to mainstream programs (Taylor-Gibbs, 1988). Interestingly, although these programs were never explicitly created for the purpose of addressing the needs of Black males, the fact that in several cases Black males comprise a disproportionate number of those served has furthered the perception that these young people are fundamentally deficient and different from the rest of the population. Increasingly, many of these programs have come under attack because there is now considerable evidence that the vast majority have done little to actually improve the academic achievement or behavior of those served (Wilson, 1992).

Despite these criticisms, there is a renewed effort to address the "crisis" facing young Black males by creating new programs based on a different set of assumptions. Often managed and directed by individuals who empathize with those served, and who often share a similar background and experience, the new initiatives are rationalized as being better able to help Black male youth because they are " culturally authentic" and "culturally appropriate" (Garibaldi, 1992). As a result of recent court challenges to the premise that not only race but gender separation is necessary, many of the programs that have been initiated in public schools have included Black girls as well. These initiatives are different from past efforts to separate Black youth in that they are not based on the premise that those served are intellectually deficient or culturally deprived. Rather, the new efforts are based on the assumption that Black youth from low income urban areas possess the potential to excel and succeed if provided with proper guidance and support in a culturally affirming environment.

Recognizing that such efforts have been implemented largely because of a growing perception that extraordinary measures are needed to address the needs of Black males, this paper will attempt to illuminate some of the risks associated with furthering the separation and exclusion of Black males and Black youth generally. In recognition of the pressing needs of so many Black youth, I will also discuss some of the considerations that should be taken into account in order to avoid the tendency for even well intentioned efforts to lead to further marginalization and reinforcement of stigma. It will be argued that in certain cases separate programs and even separate schools may be necessary to provide adequately for Black youth who have not been served well by traditional programs and institutions. However, when such arrangements are made, special efforts must be taken to insure that the young people targeted for such services are in fact being helped, and are not being marginalized and isolated by providers who claim to want to help.

Data obtained from research carried out at a continuation high school in northern California, will be utilized to examine the advantages and risks associated with racially separate programs. This case differs from most of the current efforts to support Black youth in that it was not created for the purpose of providing support and cultural affirmation. Rather, the school served as repository for troubled students considered unfit for enrollment in traditional schools. Despite the difference in its origins, I will use a description of how the school was gradually transformed over a period of four years to identify the elements that made improvement possible so that similar efforts of this kind can learn from the effort and even attempt to adapt and emulate the elements which were most essential to the school's eventual success.

The school, which shall be called East Side High School for the purpose of this analysis, (2) is particularly well suited for such a study because it originally resembled the more traditional type of intervention program targeting troubled youth. Established for students who had been removed from regular high schools for either academic or behavioral reasons, the school was widely perceived as a dumping ground for bad kids, and in many cases, bad teachers as well. The fact that Black students constituted 90% of the enrollment at the school in a district where only 40% of the students were Black, was seen as inadvertent and more related to the disadvantaged families and communities from which these children came, rather than being due to race or some secret practice of segregation. District administrators rationalized the racial imbalance at the school as an unavoidable consequence of the need to provide these students an education in a separate facility.

Interestingly, over the course of the four years in which data was collected, race played a role in several of the dramatic improvements that occurred at the school, related both to student and school performance. As the school improved, a more conscious and deliberate effort to affirm the culture and social experience of the students was adopted. In this case race went from being ignored and simultaneously implicated in the marginalization of students, to being recognized and subsequently integral to the effort to improve the school.

Given this apparent paradox, the way in which race is conceptualized and responded to in intervention efforts of this kind will also be a central theme of this paper. Much more than a combination of physical attributes and cultural traits, race is a highly politicized social formation which is treated with inordinate significance in American society (Omi and Wynant, 1986:57-50). Racial categories serve as one of the primary social boundaries between groups and individuals in American society. In a racially stratified society race also invariably becomes a signifier of power, privilege and social status. Assimilation of the dominant culture has historically served as one of the requisites for mobility and advancement, while a lack of conformity has traditionally been penalized (Baker, 1983). Despite the costs, rather than retreat from racial identification many African Americans have sought to challenge and invert the stigma associated with Black identity through various forms of affirmation (Ogbu, 1988; Hooks, 1990; Dyson, 1993). In so doing, race consciousness has played a major role in various efforts to uplift and improve conditions for Black people. As the experience of East Side High School will show, this school reform effort aimed at helping Black youth has followed a similar path.

|

|

Dimensions of the Crisis and the Nature of the Response

There is now little disagreement that large numbers of individuals, who happen to be Black and male, face an inordinate number of problems and hardships which set them apart from the rest of the US population. The preponderance of evidence supporting such a conclusion is almost mind numbing. In the labor market, Black males earn on average 73% of the income earned by white males (Carnoy, 1994). In professional and managerial positions, Black males are vastly underrepresented, and in some fields (e.g. many high tech and science related jobs), are almost entirely absent (National Research Council, 1989). Numerous studies indicate that despite the existence of laws prohibiting discrimination in employment, Black males are widely regarded as less desirable employees and therefore are substantially less likely to be hired in most jobs (Massey and Denton, 1993; Hacker, 1992; Feagin and Sikes, 1994). In urban areas, unemployment rates for young Black males are often above 50% (Wilson, 1987), and many policy analysts now regard this group as a permanent underclass deeming them "unemployable" by virtue of their lack of skills and education (Tabb, 1970; Glassgow, 1980; Archuletta, 1983). At the aggregate level, disparities in income persist, so much so that it continues to be the case that the average Black male with a four year college degree earns less than the average white male possessing only a high school diploma (Hacker, 1992).

Health indicators for black males reveal similar hardships. For the last ten years, Black males have been the only group within the U.S. population to record a declining life expectancy (Spivak, et.al.,1988). The homicide rate for black males ages 15-24 is the highest for any segment of the U.S. population and seven to eight times higher than that of white males in the same age group (Roper, 1991). Moreover, since 1980, the suicide rate for this age group has surpassed the white male rate, and all indicators point to a sharp and continuous increase (West, 1992; National Research Council, 1989). Black males are also at greater risk of substance abuse, of dying during infancy, or dying prematurely due to heart disease, hyper tension, diabetes and AIDS.

Finally, where Blacks generally, and males in particular, once saw education as the most viable path to social mobility (Anderson, 1988), it now increasingly serves as a primary agent for reproducing their marginality. In most urban areas, 20-30% of Black males drop out of school prior to graduation (Taylor-Gibbs, 1988). Nationally, Black males are four times more likely than white males to be suspended or expelled from school, and nine times more likely to be placed in special education classes (Meier, et.al.,1989). From 1973 to 1977 there was a steady increase in Black male enrollment in college, from 39% to 48% of all high school graduates; for the first time equaling the graduation rate for whites. However, since 1977 there has been a sharp and precipitous decline in Black college enrollment which has disproportionately impacted males (National Research Council, 1989). Moreover, at colleges and universities throughout the U.S., fewer than 40% of the Black males admitted to college graduate within six years. Finally, for growing numbers of Black males prison rather than college is a more probable destination during adolescence and young adulthood. In 1995, one out of every three Black males (for white males the rate is 1 out of 10) between the ages of 18 and 30, were either incarcerated or in some way ensnared by the criminal justice system (Noguera, 1995). In California, the percentage recently increased to 40% (San Francisco Examiner, February 18, 1996).

Yet, despite the overwhelming evidence that Black males are confronted with an array of chronic problems, the notion these conditions constitute a crisis is problematic. First, the term crisis implies a deviation from a more stable norm. It suggest a period of temporary urgency, or even a short term emergency, and not a prolonged and persistent degenerative condition. Secondly, the term crisis also suggest that a better and more secure period preceded the present condition, and that once the crisis is over, conditions shall return to the former state, which even if not ideal, was clearly superior to the way things are at the moment.

For African American males in the US, there is no evidence indicating that present conditions are temporary, or that by some means presently unknown, there will eventually be an improvement. Not only are the problems which particularly afflict Black males persistent, but all signs indicate escalating rather than declining severity. Moreover, while data from various sources suggests that conditions for Black males may indeed be growing worse, the deterioration is of course measured in relation to prior conditions which most observers agree have been bad for a very long time. For example, while unemployment rates for Black males in the U.S. are higher now than they were thirty years ago (Wilson, 1982), the fact that Black males were almost exclusively restricted to the lowest paying and most menial jobs at that time, and that more have now entered professional and managerial positions, suggests at the minimum that measuring real or actual progress is difficult, at least on the basis of some relatively objective criteria.

Still, there is no doubt that severe problems exist for many individuals who are both Black and male. However, can we or should we conclude that these problems are primarily caused by or somehow related to the race and gender of those individuals who experience them? Or, is there lens other than one which fixates on personal attributes which can be used to understand and study these social issues? If so, why are these social problems measured and discussed primarily in terms of race and gender rather than by some other criteria? I will attempt to provide answers to these questions as I examine some of the responses to the "crisis" that have been developed in educational institutions.

|

|

Responding to the Black Male Problem

In a probing inquiry into the problem of youth violence, Greenberg and Schnieder (1993) ask the following: "Young Black males is the answer, but what was the question?" The phrasing of the title to their paper as a question is not intended to be merely rhetorical. Rather, by playing on what has become construed as a natural association between young Black males and violence, the authors hope to compel their readers to reexamine their assumptions. This they accomplish through an analysis of the many factors (environmental, economic, etc.) influencing the incidence of homicide in five New Jersey cities. In so doing, they demonstrate that the way in which a question is posed strongly influences the framing of the answer.

By focusing almost exclusively on race and gender, other factors which may be relevant to understanding the causes of social problems like crime, drug trafficking, student performance or violence, often go ignored. Most important among the omitted factors are the influence of class and geographic location. Many, though not all, of the problems cited as afflicting Black males are most prevalent in poverty stricken urban areas. These are typically communities which lack a sustainable local economy, where community institutions are weak or barely existent, and where environmental degradation and an absence of social services are primary characteristics of the social landscape.

However, the problems facing Black males and Black youth generally are increasingly not discussed in the context of their interaction with these types of conditions. Instead, race and gender are employed as explanatory categories, resulting in an explanation of the crisis facing Black males which focuses almost exclusively on cultural rather than structural factors. For the scholars and writers who advocate this perspective, these cultural factors can include the matriarchal Black family (Glazer and Moynihan, 1963; Kunjufu, 1990); oppositional attitudes and behavior (Ogbu, 1988; Solomon, 1992; Fordham, 1991); or the violent and destructive culture of inner city streets (Anderson, 1990). Such explanations tend to reinforce and perpetuate many of the negative images and stereotypes that have historically been associated with Black males and Black people generally. In the past, propagation of negative stereotypes could be understood as the by-product of racist and racially biased theories of Black behavior. However, in the current, period these ideas are being produced by a wide assortment of journalists, scholars and political actors, many of whom perceive themselves as sympathetic to the plight of Black males, and some of whom also happen to share their race and gender.

Given the history of exclusion and given the persistence of negative images associated with Black males, good intentions often are not enough to prevent the marginalization and stigmatization of Black males even in programs that were theoretically designed to help them. Particularly if efforts designed to help Black youth are based on the assumption that race and gender are the key attributes which must be addressed in order to help them, such efforts may only overlook other important factors related to the social and economic conditions in which young people live which have tremendous bearing on their behavior and attitudes. Moreover, such formulations may also inadvertently reify the stereotypes and images that have been instrumental in maintaining the subordination of poor Black youth in the inner city.

The efforts undertaken by a middle school in an economically depressed section of West Oakland to address the problem of disruptive students illustrates how an intervention designed to help Black males can end up producing the opposite effect. (3) I had been working with the school as a research consultant on a school reform project and was approached by the principal to assist in devising a strategy for addressing discipline problems at the school. Teachers had been complaining for some time to the site and district administration that they had too many disruptive students and that many of them felt unsafe at school. The teachers argued that the disruptive students were preventing others from being educated because a few individuals took up most of the class time. The district administration had been pressuring the school to improve its test scores for some time, but was unable to get cooperation from the teachers because they insisted that the disciplinary issues should be addressed first. Finally, in an attempt at responding to the faculty's concerns, the school was offered an additional teacher who would be assigned to work exclusively with the disruptive students.

Teachers were asked to put forward the names of their most difficult students. The principal then created a list of the names which came up most frequently, and these students were selected for placement in the new class. Not surprisingly, given the history of behavioral problems at the school, all twenty-one of the students selected were African American males. To address their special needs and to insure that the students would be helped, the district assigned a young Black male teacher, who was specially trained in Afrocentric education, to teach this newly created class. Once established, the class was publicized as a unique and "innovative educational opportunity" which in addition to providing a culturally enriched curriculum, would also provide work experience, mentors and other special services for its students. If successful, the district administration planned to use the class as a model at other schools throughout the school district. (4 )

Despite these efforts, it became clear within a relatively short period of time that the class was a complete failure. Trapped together in the same classroom for four and a half hours a day, and isolated from the rest of the school, the students soon began to resent their placement in the special class. Much of this resentment was taken out on the teacher, who had grown increasingly short tempered and authoritarian toward his class as the frustration of the students escalated. He also became extremely resentful toward the district administration once it became clear that much of the support that had been promised either would not be delivered, or would take some time before becoming available. During my own observations of the classroom over the six weeks that it remained in operation, it was apparent that tensions between the teacher and students were high, and both parties complained openly about being unfairly trapped with each other.

What was perhaps most interesting about this pilot disciplinary program was that when I interviewed other teachers at the school about how their classes were going now that the disruptive students had been removed, several pointed out there were now a number of students who previously had not given much trouble but had now emerged as new trouble makers once those who had been identified as disruptive had been removed. Some of the teachers even suggested that what was needed was at least one more separate classroom for the other disruptive students.

Cases such as this one demonstrate clearly how easily a well-intentioned intervention targeted at a particular group of students can degenerate into a dumping ground for individual students who are seen as difficult or even undesirable. Without any mechanisms or procedures in place to insure that high educational and program standards are maintained, such a program can easily become a convenient way of excluding children with special needs from the educational mainstream. Moreover, there exists a substantial body of research which shows that whenever a group of students are labeled deficient, dysfunctional, disadvantaged or different in any negative way, that there will be a tendency for those students to receive services of inferior quality (Milofsky, 1974; Wilson, 1990). This example also shows that by not addressing the factors that contribute to disruptive behavior, such behavior can resurface among other students.

The prevalence of such examples also makes it essential that there be an examination of the potential dangers associated with overemphasizing race and gender in explaining or responding to social problems in schools. Many of the initiatives undertaken to address the needs of Black males may further isolate and exclude Black males from college preparatory classes and other academic opportunities. The call for separate programs to educate and serve the needs of Black males can undermine efforts to assure equal treatment in education because these can be interpreted as being warranted because this segment of the population is more dangerous or difficult to handle. Even if the rationale is never articulated, programs that allow for some degree of separation may be supported because they serve as a means to spare the rest of the student population from the contaminating influence of difficult students. For these reasons, those who call for separate programs out of the belief that this is indeed the best way to serve Black youth must be aware that such actions can run the risk of inadvertently isolating the young people served and reinforcing negative images and stereotypes.

|

|

Separate and Unequal: The Re-making of East Side High School

Located in a densely populated urban community in northern California, East Side High School had long served as a repository for students regarded as too difficult for traditional high schools. Though officially designated a continuation high school, in the 1960s and early 1970s the school had once functioned as a less structured alternative school, providing smaller classes and a less regimented learning environment for students who had encountered trouble in larger, more impersonal high schools. In those days the student population was diverse, with respect to the racial and socio-economic status of the students, and the school curriculum emphasized the arts and creative writing as a strategy for tapping into the intellectual potential of its unconventional students. It was known as a "hippie" school, operated in accord with the counter culture values and aspirations of its teachers and kids who wanted and needed an alternative to the bells and rules of traditional schools. With fewer than 150 students it provided an intimate learning environment for those it served, and was widely regarded as successful, at least for the outcasts that it served.

By the late 1970s the school had changed. The white students from affluent families were no longer present, and the alternative curriculum which emphasized creativity and experiential learning had been replaced by one which emphasized remediation. The school had gradually become a dumping ground for students whose behavior, academic performance or attendance rendered them unfit, uneducable and undesirable in the eyes of administrators at traditional high schools. Likewise the faculty, which once consisted of talented idealists who functioned more easily in a less structured environment, had gradually become burnt out and cynical. Increasingly, the new teachers assigned to the school were distinguished only by their interest in a shorter teaching day, and by the fact that like the children they served, they too had been pushed out of the traditional schools.

By the mid 1980s, East Side High was little more than a temporary custodial facility for young people who seemed headed for futures of welfare dependency, prison and dead-end jobs. During my first visit to the school I saw classrooms with fewer than a handful of students present. (5) Bored and listless, occasionally filling out a ditto or resting their drowsy heads on their desks, they seemed more like students unhappily serving detentions after school, than students engaged in learning. Seated at their desks, reading magazines and newspapers or sipping coffee, their teachers seemed to be just as lethargic as the students.

On my first visit it seemed like all the action at the school was occurring outside of the classroom. Kids were gathered around cars in the parking lot with radios blaring. The distinct smell of marijuana hung in the air and kids could be seen openly passing joints back and forth after taking their turn at sucking deeply and holding in the smoke. Groups of students were clustered about engaged in animated conversation and various forms of play, while a group of boys hovered near the ground at the corner of the building over a pair of dice, occasionally bursting out noisily in response to their victories and losses.

This was a school in name only, and the fact that it served kids who had been labeled as nothing more than juvenile delinquents, unwed teen mothers, gang-bangers, drug users, and academic failures, made it possible for the school to remain in its miserable state indefinitely. An unwritten understanding governed relations between adults and students at East Side High: as long as the adults didn't challenge or raise objections about the behavior of the students, the teachers could come and go from work in peace. The live and let live philosophy of East Side assured that there would be few disturbances involving adults and students at the school, and for as long as peace prevailed, intervention from the district administration was unlikely. The fact that test scores were low, attendance abysmal, and few students graduated, did not generate much concern. (6) These were after all "high risk" youth, whose background of poverty and problems made it unrealistic to expect more than was produced.

East Side was also a segregated school, though not officially or openly designated as such, and its presence provided the district with a convenient means for dispatching students whose needs were perceived as too difficult to meet at a traditional comprehensive high school. In its official pamphlets the district described East Side High School as a specially designed alternative educational program for "at risk" students. Pointing to its smaller class size (16:1 compared to 30:1 at most regular high schools), the district took credit for providing a more expensive educational alternative for its neediest students. The fact that it was comprised almost exclusively of minority students (90% Black, 8% Latino, 2% Asian) in a district that took pride in its commitment to integration (42% white, 38% Black, 10% Latino, 10% Asian), was explained as an inadvertent form of segregation that could be justified because of the help and support that the school provided. Tucked away at the margins of this community and school district, East Side was a bit like a mad uncle who had been confined to the attic lest his crazy antics embarrass and bring dishonor upon a decent family.

All of this gradually began to change when a new principal was assigned to East Side in the Fall of 1988. Glen Peters was originally sent to the school to serve as its principal as a way of forcing him into retirement. Over the years Peters had earned a reputation as a maverick administrator and outspoken advocate for Black students. After 35 years of service as a principal and numerous battles with district level administrators over the treatment of Black students, his superiors finally decided that the best way to rid themselves of this gadfly was to dispatch him to East Side, where they hoped the combination of chaos and complacency would drive him to early retirement. Already 63 at the time of the move, Peters was indeed growing tired from the years of skirmishes with senior administrators, and saw the assignment as a brief final tour of duty before leaving his career in education.

However, Peters experienced a rejuvenation of the idealistic impulses that had originally drawn him to education when he arrived at East Side. Rather than becoming demoralized by the malaise that pervaded the school, his encounters with students led him to immediately recognize not only their many un-met needs, but also their potential for higher performance if provided the opportunity to learn and develop. Moreover, he saw in this marginal school an opportunity to re-create an alternative learning environment at the school, similar to what had been there before, but modified to serve this predominantly Black population of students. With a small enrollment (by 1988 there were only 112 students officially enrolled), and even fewer attending each day (less than 50% on the average day, less than 70% on Mondays and Fridays), he imagined the possibility of creating an alternative school that could serve the needs of students who had long been written off as unteachable and undesirable. The fact that the school was in effect segregated also represented an opportunity to Peters, for he knew that few objections would be raised by the district administration if he attempted to implement innovative educational changes that responded to what he perceived as their un-met need for cultural affirmation.

Though a visionary, Peters was also a realist, and quickly recognized that changing the school environment would be difficult if not impossible with the teachers who were working there. Since removing teachers is almost always an extremely difficult process, regardless of how poor their performance, Peters attempted to get around the problem by recruiting concerned adults to support and work with students at the school as volunteers. I was one of the first individuals recruited by Peters to volunteer at East Side. At the time, I was working as an official in a municipal government and Peters showed up at the office unexpectedly with a young man who was one of his students. He introduced the student, and informed me that he was a natural leader. His reason for showing up at my office was that he wanted me to encourage the young man to run for student body president at East Side High School.

As Peters spoke, I took my time studying the young man before me. He had three long gold chains draped over his neck, several large gold rings on his fingers, and a beeper attached to his belt. Based on his appearance I immediately concluded that the student must be a drug dealer, and I wondered why my friend wanted to see him become a leader at the school. However, after a few minutes of conversation it became clear to me why the principal wanted to encourage this young man. Not only was he articulate and intelligent, it was also evident from the confidence he projected that he was charismatic, and undoubtedly admired by his peers. In fact, I was so impressed by him that after our meeting I volunteered to work at the school.

Like Peters, I immediately saw the potential of the students and the school. Despite the disorder that prevailed, I liked the small size of the school and the easy going atmosphere. To a large extent, my interest was inspired by my recognition that I had once been a lot like the young man that Peters brought to my office. Though I had been successful as a student, I had seen my share of trouble in school. However, unlike him, I had the benefit of two employed and supportive parents, and the good fortune of not growing up during the middle of the crack epidemic. After that short first visit I was able to recognize enough of myself in that student and others to commit to working with Mr. Peters at East Side High School.

|

|

The Transformation of East Side High

For the purposes of this analysis, I will reserve my discussion of school change at East Side to those aspects which are most germane to understanding how the school managed to serve marginalized students without furthering their marginalization. To a large extent, this involved balancing the advantages created by the school's invisibility in the school district, and directly confronting the circumstances which constrained the ambitions and opportunities of the students. Maintaining this balance involved using the marginality of the school and its students as an opportunity, while simultaneously challenging the forces which rendered these young people at-risk and vulnerable. Such an approach meant living and working with certain blatant contradictions that entailed a high degree of risk if not handled carefully. However, we understood that if we managed to work within this balance, new opportunities for change could be created.

East Side was such a low priority within the district that after the previous principal retired it took the district six months to select a temporary acting replacement. This also proved to be a benefit since the school's position within the district made it possible to experiment with educational reform without incurring the scrutiny of district administrators. One of the ways in which this was done was by enlisting individuals from the surrounding community to volunteer and work at the school in a variety of roles. Early on, Peters had come to recognize that without adults who could identify with the students at East Side, very little could change. Many of our students were hardened from their past difficulties in school and the tough lives they led on the streets. These were not the kinds of students who obeyed and respected teachers simply because of the position they held. On the contrary, these students viewed most adults with suspicion, and only showed respect toward those who they felt had proven themselves worthy of such treatment. From my interviews with them, I came to see how many of the young people had become suspicious of adults because the primary consumers of crack were adults aged 25-45. Many of the female students had relationships with adult men, some of whom were fathers to their children. Hence, for these kids, age alone was no criteria for special treatment.

The adults we recruited to the school were African American and most came from the same community as the students. Some were professionals, but most of the others were skilled and unskilled workers, lacking in college education. The one characteristic shared by all of those recruited was that each had a genuine interest in the students and gave freely of their time to the programs we devised. Most of those we recruited served as guest speakers for particular classes, but some volunteered on a regular basis as tutors, un-official career and college counselors, and coaches. By incorporating these adults into our plans we were able to further reduce the ratio of adults to students at the school. More importantly, we increased the possibility that students would be able to form intimate relationships with adults with whom they could discuss personal problems and issues, as well as plans for the future.

Perhaps the most important change which occurred at the school during this period involved the curriculum. Over a four year period East Side High School went from offering little more than remedial classes in every subject, to a rich and varied curriculum which was geared toward the diverse interests of our students. Courses with titles such as Street Law, Math in the Modern World, Community Based Film Making, Black Women Writers, Social Living, Afro-Haitian Dance, African Art, and Chicano Politics and Culture were offered to students. This transformation in course offerings was made possible by the steady influence of Glen Peters, who prodded the faculty to develop new and exciting courses that would elicit the interest of our students. Not all of the teachers welcomed the opportunity to change what they had been doing in their classes. In fact, some resented the manner in which Peters pushed for change. However, Peters was relentless. While never antagonizing the teachers, he consistently used every faculty meeting as an opportunity to discuss what more the school staff could do to make school relevant and interesting to students.

Eventually, most of the teachers grew tired of resisting Peters and gradually began to give in. Two of the more senior teachers retired, while another two requested and received transfers to other schools. With four new teachers, Peter was able to create a new dynamic in the school, one which encouraged optimism and enthusiasm from all of the school staff. A senior counselor from a local high school who heard about what Peters was attempting to do at East Side, requested a transfer to the school so that she could join in the effort. Perhaps most interesting of all was the gradual change in attitude that took place among the remaining teachers. With so much activity and innovation taking place at the school these teachers also became motivated to create new courses, and they too began to move away from remedial instruction to a more interactive and challenging style of teaching.

During this period, I offered a course in African American History which I taught each morning, five days per week, at first period. Though many students complained about the 8:30 a.m. starting time, it was the only time slot that fit my schedule. Even if still sleepy when they arrived, attendance was generally good, and demand for the course remained high for all three of the year that I taught at East Side.

In addition to teaching, I used my visits to the school as an opportunity to study the transformation that was taking place, and to interview students. My interactions with students at East Side had triggered a desire on my part to understand more deeply how these young people were coping with the many dangers and risks that they confronted in their communities. I wanted to understand how they were coping with these pressures and I wanted to learn how or if education fit into their plans for the future. I hoped that by asking questions of this kind I might learn something about the types of programs that might be best suited to serve their needs.

|

|

Are They Really Being Helped?

Student Perceptions of East Side High School

Over the course of two years, I interviewed 113 students, nine teachers and two administrators (the principal and guidance counselor). I also spoke on a regular basis with the school secretary and the student monitor whose job it was to provide security at the school. The interviews were important in providing me with insights into how those who worked and attended the school perceived their participation within the school community. This was important because I wanted to know how the changes that had occurred at the school were perceived by adults and students. Even though I was no longer completely an outsider at the school, the fact that I was a university professor placed me in a different role and relationship to the school. Unlike the others, my salary was not based on my work at the school and I did not have to be there. Moreover, during the three years in which I was working at the school I had been closely identified with the school's leadership and with the measures that were undertaken to improve the school. For this reason, I needed to find ways to understand how the others perceived the school and the changes that had occurred rather than relying simply on my own observations.

For the purposes of this paper, I will focus this part of my analysis on the perceptions of the students since in most cases they had not voluntarily chosen to go to East Side, and in some cases had been placed there as a form of punishment. Understanding how they made sense of their experience at East Side in comparison to prior school experiences, was important for determining whether or not the students felt marginalized by the placement.

The most consistent theme that emerged from a review of the student surveys is that the students gradually came to see their placement at East Side as an opportunity rather than as a form of punishment. In the interviews, the majority of students readily acknowledged their past problems in school. Truancy, fighting, defiance toward teachers and adults, are just some of the behaviors which the students admitted to which led to their being placed at East Side. (7) Several described themselves as being "out of control". For many of such students, being placed at East Side provided them with the second chance they needed to complete their high school education. The excerpt from the interview presented below is representative of how many of the students described their past problems and their adjustment to East Side.

Q: Why did you leave your last school?

A: I was barely going to school, and when I did go, I mostly just got into trouble. In fact, if I wasn't suspended I was in the principal's office or the in-school suspension. I don't think I was hardly in class at all.

Q: Why do you think that you were getting into so much trouble?

A: I'm not really sure. I guess part of it was that I was just young and trying to prove how bad I was. Being a ninth grader in such a big school I wanted to show people that they couldn't mess with me. But I guess part of it was that I thought I could just get away with it. We had so much freedom there. The teachers didn't seem to even care if you went to class. At least that's what I thought till I got my first report card.

Q: What about East Side? Has it turned out to be they way you expected it?

A: At first when they told me I was going to continuation school I was mad because I thought that was like a reform school. I didn't want to be in a school for bad kids, cause even though I was bad in ninth grade, I was pretty good in elementary and junior high. I thought there was going to be a lot of fights at this school. But really, its chill here. I mean everyone here is bad so you don't got nothing to prove. And the teachers are real cool. They really want to help you and make sure you learn something. (8 )

The notion that East Side was a better school because of its small size and caring teachers, was expressed by many of the students in the interviews. Several students pointed out that whereas at their former school "it was like going to a fashion show", due to the pressure to wear the "right" clothing, at East Side most students said that they didn't have to be preoccupied about their appearance. Many of the social pressures created by the impersonal environment of larger schools, such as the need to affiliate with cliques or gangs, was also less pronounced at East Side. According to one of the students that was interviewed: "It don't really matter who you kick it with at this school cause every body hear got a rap sheet this long (pointing down the length of his arm). There ain't nothing to prove here and people don't trip so hard about who hangs with who. We're all here cause we fucked up, so everything else is bullshit." (9)

Several students spoke favorably about the teachers at East Side and the support they received from them. Their comments confirmed much of what has been found in the research on effective teaching for Black students (Foster, 1989; Foster, 1994; Ladson-Billings, 1994) During the interviews, we pressed the students to be specific about which teachers they liked and what they liked about them. Two names were cited most frequently by the students, both were veteran teachers who had worked at the school for many years, and interestingly one was Black and one was white. When asked what is was about these teachers that made them good in the eyes of the students, the qualities most frequently cited were: firmness, compassion and an engaging style of teaching. Students described the two individuals as being like mothers, aunties and big sisters, and spoke of being inspired to work hard, and learning interesting and relevant things, and feeling respected.

Surprisingly, the majority of students we interviewed said that they actually preferred strict teachers who as one student put it, "don't put up with no bullshit from the students. They let you know who the boss is." According to another student "If a teacher is scared of me they can't teach me. I can tell if they's scared, and if they is usually you can do what ever you want in their class. I can respect a teacher that's strict and really tries to get the kids to learn something." (10)

However, the students were also quick to point out that it wasn't only strictness that they admired, for they also wanted to know that the teachers cared about them. The two teachers cited most frequently were described as caring individuals who took a sincere interest in their students. One student described one of the teachers in the following manner: "I love Ms. Wagner. She's like a mother to me. In fact, she's done more for me than my mother cause my mother has hardly been around. Ms. Wagner really cares about me, that's why I never disrespect her like I do them other teachers. She's a really kind person who has helped me to believe in myself." (11)

Finally, the students said that the teachers they admired were demanding academically and that they made their classes interesting. These teachers found interesting ways to present material to students, and were among the first teachers at the school to expand the curriculum by offering new classes. One female student described the other exemplary teacher, Ms. Sturn, in the following way: "Ms. Sturn is a serious woman. You can't be going up in her class with no books or pencil. She'll come straight out and ask you why is you there? And she definitely don't want to hear no excuse about how you forgot to bring your books or pencils. She puts you to work as soon as you walk in the door, and most of the time the work is something that's fun to do." (12)

Comments such as these reflected a belief that was shared widely among the students: East Side High School provided a real opportunity for students who had failed in school to be successful. Undoubtedly, that perception was based largely on a comparison with their prior experience at other schools. The vast majority of students at East Side had experienced problems in school, and many had been labeled as "troubled" or even "uneducable" by teachers, counselors and administrators. East Side gave many of these students a second chance; and an opportunity to be successful in school and for some, to even go to college. Though many had originally resented being placed at East Side, their experience there had gradually led them to see that there could be benefits from going to such a school. As evidence of the success achieved at the school, by the Spring of 1992 the average daily attendance rate had improved to 74%, the graduation rate had climbed to 68%, and several of those who graduated went on to attend two year and four year colleges. Absent of the pressures and distractions of larger schools, East Side could provide its students with an educational alternative that met their needs. The fact that this occurred in isolation from students of other racial backgrounds with higher levels of academic performance, did not seem to deter from its ability to accomplish this goal.

|

|

Conclusion: Insuring That Support is Provided

The experience of schools like East Side High School provide a concrete example for understanding how disadvantaged African American youth can be assisted without being marginalized. The fact that such help can be provided in a racially separate setting is important because there are so few examples of programs that are effective at serving the needs of low income minority students. The failure of urban public schools in particular is so widespread that in many cities such schools serve only those too destitute to escape them (Maeroff, 1988). The situation has become so intolerable that many districts are experimenting with new approaches to education which depart significantly from past practices. Vouchers, various forms of choice, privatization and contracting out, are just some of the more well known proposals being debated by policy makers (Gross and Gross, 1985). At the same time, community groups and parents are pushing for reforms at the local level which provide greater accountability, autonomy and control. Charter schools, site based management and various forms of cultural enrichment, such as Afrocentric schools, are just some of the reform measures that are being implemented in schools throughout the country (Steinberg, 1996).

Given the chronic nature of the problems facing so many urban schools, attempts at innovation are to be expected and perhaps encouraged. Parents are increasingly frustrated by the inadequacy of the schools their children are compelled to attend and are demanding alternatives. However, in the rush to challenge the status quo there are risks. Not all of the changes being promoted and attempted will lead to actual improvements in the education of children, and some may in fact worsen the situation if they lessen the degree of public accountability (Noguera, 1994). Particularly in the case of poor African American children, who historically have been among the most neglected and least sought after by educational institutions, there is good reason to be suspicious of any effort which claims to help them by isolating them into separate programs.

For this reason, it is important that any reform initiative be evaluated on the basis of whether it in fact brings tangible benefits to those it was intended to serve. Good intentions simply are not good enough, even when the services are provided by individuals who would seem to have an interest in insuring that high standards are met.

This caveat might seem simple enough to enforce, but in the politicized atmosphere that presently surrounds school reform efforts, such quality control assurances can be difficult to secure. Advocates for change are likely to ask for additional time to allow their experiments to mature, and may challenge those who question their approaches on ideological rather than substantive grounds. This is what occurred at another high school in northern California, which because of its dismal record, was turned over to a group of African American educators to become a model Afrocentric school. After four years of reform, and nearly one million dollars in funding to support the effort, the school continues to be plagued by poor student performance, high drop out rates, violence and delinquency. (13) Such results are not necessarily the fault of Afrocentric approach, but it may be related to a flawed understanding of the problems of the school and needs of the students. I would argue that by focusing exclusively on race through efforts to design and implement an Afrocentric curriculum, those involved overlooked a vast and complicated array of factors which also influence the student and school performance. Furthermore, the lack of careful evaluation and the inability of district administrators to hold those who undertook the experiment accountable for their work and the funding they received, contributed to the failure of the effort.

The experience of East Side High School shows the complicated ways in which race can be used to either marginalize or to find solutions to some of the problems facing Black males and Black youth generally. While it served as the district's dumping ground it was possible for district administrators to ignore the plight of the school because it served students who were perceived as undesirable, and because their parents had no political clout or influence to challenge the district's policy of benign neglect. However, the school's marginality also made it possible for a group of committed educators to experiment with educational innovations and quietly transform the school with minimal interference from district administrators. In a school that served primarily Black students, it was essential that part of the change effort aimed at finding ways to affirm the culture of the students and find practical ways to address the challenges they faced growing up in impoverished urban communities To a large extent, this could only be done by recruiting a staff capable and committed to serving the students' needs and developing a curriculum which was relevant to their goals and aspirations.

Despite the success created at East Side, this experience also suggests that efforts to provide assistance to African American youth must be careful about how race is used in analyzing problems and formulating responses. The failure these students experienced in school prior to coming to East Side, can not be explained by race. Racism may have been a factor influencing the difficulty that teachers and other school officials had in working with these students. Research has shown that Black students are more likely to be judged by their willingness to adopt conforming behavior (Leacock, 1970; Lightfoot 1973), and most of East Side's students had long records of discipline problems in school. However, race can not be seen as the cause of these students problems given that not all Black students are sent to East Side, and so many other factors have influenced their experience in school. There is a long history of educators fixating on the attributes of students as an excuse for failing to serve them well (Payne, 1986). Given this history, it can be dangerous to design educational interventions that over emphasize the significance of race, even if done for the purpose of countering the effects of racism, for in so doing one can inadvertently lapse into the attributionist approach to understanding educational issues, and as a consequence, fail to respond to the broader needs of students. Put more simply, if we reject the notion that race is the cause of student failure, we must also be critical of any effort which over emphasizes the role of race as a prescription for amelioration.

Critical educators and researchers must remain skeptical of any approach that offers simplistic solutions to the complex problems facing African American students. This is not to say that educating African American children is so hard that only specially trained experts can figure it out. However, given the history of miseducation, of failed experiments, of wasted resources, and the consequences that all of this has had upon Black youth, a strong dose of healthy cynicism seems to be in order.

|

Published in In Motion Magazine June 2, 1997.

|

|

|