EDUCATION RIGHTS

Taking Deeper Learning to Scale

- The Elusive Search for Equity in an Affluent School District

- 2013 California State Test: English Language Arts and Math

- Deeper Learning Comes to Brockton

- Deeper Learning In the Deeper Part of Hell

- Final Thoughts on Taking Deeper Learning to Scale: From NCLB to ESSA

- Charts & Footnotes | References

Pedro Noguera, PhD

Dean, Rossier School of Education

Distinguished Professor of Education

University of Southern California

September 15, 2023

For some time now it has been evident that the policies the U.S. has pursued to elevate the academic performance of students, particularly those who are most economically disadvantaged, have not produced the results that were promised or hoped for. Several highly regarded studies have shown that No Child Left Behind, Race to the Top and other related policy initiatives designed to raise academic standards and increase accountability on schools through standardized testing, have not led to significant gains in achievement (Hanushek et.al. 2012; Education Week Quality Counts 2017; IES/NCES 2016; Brown 2017). In 2015, math scores for fourth and eighth graders dropped on the NAEP (National Assessment of Educational Progress – widely regarded as the best indicator of student performance) for the first time since 1990, while scores in reading have dropped or remained stagnant since 2013 (Strauss 2015). Meanwhile, scores on the SAT and ACT have barely improved particularly as the number of test takers has increased. 1

Results from the recent PISA (Programme in Student Assessment – an exam given to students in 35 industrialized nations which provides an international comparison of academic performance) are perhaps the most telling indication of America’s educational challenges. U.S. scores in reading and science were nearly the same as they were three years ago, leaving Americans near the middle of the pack among the 35 nations that participated in the assessment. Results were lower in math in 2015 compared with 2012, placing the U.S. near the bottom. Singapore was the top performer in all three subject areas. According to Andreas Schleicher, Director of education and skills of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD), “Students are often good at answering the first layer of a problem in the United States. But as soon as students have to go deeper and answer the more complex part of a problem, they have difficulties,” Schleicher said. (Richmond 2016)

Indications that there are serious problems with respect to educational performance in the US are most evident among poor and minority students. In 2011 25% of African American students and 17% of Latino students attended high schools the US Department of Education labeled as dropout factories — a school in which 12th grade enrollment is 60 percent or less of 9th grade enrollment three years earlier. This compares to only 5% of white students (Balfanz, R., Bridgeland, J., Bruce, M., & Fox, J. Hornig, 2013). Although graduation rates have risen in recent years to a all time high of 82%, throughout the country, large numbers of students who graduate and pass state exams are required to enroll in remedial courses in math and English when they enter college.2

Lack of progress combined with growing opposition to high stakes testing, has led a growing number of educators and policy advocates to conclude that education policies and the strategies used to help under-performing schools and to promote student achievement must change. Some have called for a more deliberate focus on creating conditions that promote highly effective teaching and that support more deeply engaged learning (Alliance for Excellent Education 2016; Noguera, Darling-Hammond and Frielander 2015). That is, rather than relying on accountability (via high stakes testing) as the primary lever used to produce higher levels of achievement, and holding schools and the educators who work in them accountable when they don’t, there are a growing number of advocates calling for a policy that develops the capacity of schools to meet the needs of students.

The adoption of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS or some similar version has been adopted by forty-two states) emphasizes the need to ensure that all students have access to deeper learning opportunities. Deeper learning generally refers to the utilization of higher order thinking capacities and learning experiences that includes: critical thinking, problem solving, independent research, evaluation, comparative analysis, and the opportunity to acquire the skills needed for college and career readiness (Noguera, Darling-Hammond and Friedlaender 2015). To prepare students to meet these standards schools are expected to create “fewer, higher and deeper” curriculum goals (Darling-Hammond, 2010) so that students can develop their intellectual competencies. This includes a flexible understanding and an ability to apply core academic content to real-world issues and problems, as well as an ability to work collaboratively, to communicate effectively, and to learn how to learn (NRC, 2012). As I will show in the pages ahead these learning goals are not currently available in many schools, particularly to the most disadvantaged students.

With the adoption of the CCSS many states have developed more complex forms of assessment to both support and evaluate these college and career ready standards. The multiple-choice tests that have been used throughout the United States primarily measure low-level skills of recall and recognition (Yuan and Le, 2012). New assessments developed by two consortia of states — PARCC (Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers) and the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC) include more open-ended tasks and complex problems that are designed to evaluate higher-order thinking.

However, if the tests are to serve as a lever for moving schools to expand and deepen learning opportunities for students, a tremendous transformation in how schools approach teaching and learning will be necessary. While high stakes testing has succeeded in getting schools to become more focused on achievement as measured by test scores, it has also led many schools to adopt scripted curricula and test preparation as “high leverage” change strategies. Such interventions have been especially common among schools serving large numbers of low-income and “high need” students (e.g. English language learners, students with special needs, over-age and under credited students, etc.). Many of these schools were already struggling to meet the previous lower standards. As states raise the academic bar, new systems of support and a concerted effort to build the capacity of teachers and schools will be needed to avoid a massive increase in the number of students and schools that are deemed to be failing.

It is important to understand the significance of the shift that will be required for states to move to a capacity building approach given that the accountability strategy that has dominated state and federal policy has been in place for the last 15 – 20 years. Under the accountability regimen created by NCLB, states applied pressure, and in some cases sanctions, on struggling schools when improvement as measured by student test scores did not occur. Such an approach fostered compliance but largely ignored the need to provide resources, guidance and support to schools so that they could be more successful in meeting the needs of students. It also did very little to develop the professional capacity of educators which has proven to be particularly problematic for schools serving the most disadvantaged and vulnerable students. More often than not, such schools have been labeled failing and subjected to a variety of sanctions including the removal of personnel (principals and teachers), reconstitution, state trusteeship (i.e. takeovers) and even closures (Center for Education Policy 2011). Following the enactment of Race to the Top such sanctions became common and pervasive.

Gradually, states and eventually the federal government came to realize that this approach has not been working. An analysis of achievement patterns in all 50 states reveals that demographic factors such as poverty, race and language are the strongest predictors of school performance (cite). Moreover, several states experienced a growing “opt out” movement as more and more parents began refusing to allow their children to take high stakes exams. The combination of these and other factors led Congress to adopt the new Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which has significantly scaled back state testing requirements. 3

It is too early to know whether or not ESSA will be any more successful than NCLB in moving the nation’s schools forward. Thus far, there is little reason for optimism given that most states have yet to adopt strategies that would make it possible to effectively provide support to schools that have historically struggled. In an effort to explain why the US has not made more progress in its efforts to improve schools, Canadian education policy expert Michael Fullan argues that US policy makers have relied on the wrong “drivers” to spur improvement. He writes: “…policies and strategies must generate the very conditions that make intrinsic motivation (of educators and students) flourish.” (2014: 5) He goes on to add: “The right drivers – capacity building, group work, instruction, and systemic solutions – are effective because they work directly on changing the culture of school systems (values, norms, skills, practices, relationships); by contrast the wrong drivers alter structure, procedures and other formal attributes of the system without reaching the internal substance of reform – and that is why they fail.” (p. 6)

Drawing on Fullan’s notion of the “right drivers” in the following paper I analyze the factors that limit or help to create conditions for changing the culture of school systems so that highly effective teaching flourishes and deeper learning is embraced as a strategy for improving academic performance. I also analyze why race and poverty are often perceived as obstacles to deeper learning, particularly in schools struggling to find ways to raise student achievement. Finally, I use three cases to explore what it will take to make deeper learning opportunities available at a larger scale than they are now.

I begin by profiling an affluent school district 4 that seems to have all of the resources needed to ensure that the educational needs of students are met, yet, for a variety of reasons remains stuck in a system that is highly tracked and where traditional approaches to teaching and learning (e.g. lecture) are pervasive. I use this case to show why the district’s efforts to reduce disparities in student learning outcomes (the so-called achievement gap) that correspond to the race and class backgrounds of students, have gained little traction despite a pledged commitment and genuine desire from educational leaders and policy makers to address the issue. The case is important because the disparities that plague this district are common in schools throughout the US. The case serves as a useful means to draw attention to the obstacles that many schools encounter in using “deeper learning” as a lever for change.

From there, I profile Brockton High School (BHS) because it serves as a useful case for illustrating how deeper learning can be used as a strategy to raise achievement at a large school with a low-income, minority population. I examine how the school managed to overcome internal and external obstacles as it implemented changes in teaching and learning in the hope that other schools attempting to follow a similar approach might learn from the Brockton model. I also examine the role of the district central office in supporting efforts at BHS to make deeper learning more widely available to students since it is helpful in understanding how such strategies can be used to leverage change at other school sites and make it possible for deeper learning to be taken to a larger scale.

Finally, I profile a high school in an impoverished community that has been struggling with low student achievement and poor school performance for many years. I use the case to illustrate how teaching strategies that foster deeper learning can be implemented in high poverty schools and to show the potential of deeper learning to serve as a lever for broader school change. I also explain why the school’s leadership was largely unable to recognize the potential for deeper learning to promote improvement and address some of the other challenges facing students because of their preoccupation with raising test scores.

At the conclusion of the paper I offer some reflections on the policy changes that are needed to implement deeper learning strategies at a larger scale and the supports that schools will need to so that they are able to become more effective in meeting the needs of the most vulnerable students.

The cases presented reveal the potential of using deeper learning as a reform strategy and as a means to achieve greater equity in academic outcomes. Equity is the critical challenge facing American education today. As a result of rising child poverty rates (since 2008 1 out of every 5 children in US schools comes from a household in poverty and just over 50% of all public school students now qualify for free or reduced price lunch) and changing demographics, many schools are struggling with producing equity in academic outcomes (Noguera 2016). My hope is that by drawing attention to schools that have met these challenges successfully, and the obstacles that have prevented others from obtaining similar results, it may be possible to promote greater progress elsewhere. Learning from success may sound like a common sense approach to education policy, however for the most part this has not occurred in American education. Since the enactment of No Child Left Behind the policies and strategies that have been promoted at the state and federal level have largely ignored the need for schools to create conditions that promote teaching that challenges, stimulates and engages students. We may now have arrived at a moment when in at least some states and communities there is greater interest and willingness to change policy and practice so that this can occur on a greater scale than it does now.

THE ELUSIVE SEARCH FOR EQUITY IN AN AFFLUENT SCHOOL DISTRICT

The Oceanside Unified School District (OUSD) is widely regarded as having some of the best public schools in the state of California. With high scores on standardized tests, excellent graduation and college attendance rates, and a high Academic Performance Index at most of its schools, OUSD is widely perceived as successful. Its stellar reputation is well known throughout the region, and for this reason, its schools attract students from many surrounding school districts who utilize inter-district transfers to enroll.

However, despite its excellent track record, OUSD schools are characterized by wide and persistent disparities in academic achievement and long-term academic outcomes. Specifically, while White and Asian American students have on average performed at relatively high levels, while African American and Latino students have historically performed at much lower levels. The persistence and pervasive nature of these disparities, despite several high-profile efforts to address them, suggests that schools in OUSD are unclear about how to meet the educational needs of minority and socioeconomically disadvantaged (SED) students. Closer examination reveals that even students who do well academically describe themselves as unchallenged, bored and largely unmotivated in most classrooms.

In its search to find ways to reduce and hopefully eliminate persistent disparities, in 2015 the district undertook a major equity initiative aimed at identifying the barriers to improved academic outcomes for minority and low-income students. For over twenty years, OUSD had undertaken a number of initiatives to reduce racial and socio-economic disparities in student achievement. However, for a variety of reasons, none of these efforts were successful in producing significant or sustainable improvements in academic outcomes for African American and Latino students, English language learners, children with learning disabilities and low-income students generally, in the school district. The 2015 equity study showed that several factors contributed to a lack of progress: a high rate of turnover in leadership at both the district and site level, a failure to implement and evaluate new initiatives aimed at improving teaching to ensure fidelity in implementation, political distractions and a wide variety of institutional obstacles. Most importantly, the equity study found that there was a lack of clear and consistent focus on how to deliver high quality instructional support to all students.

The equity study consisted of the following: A quantitative analysis of educational achievement across the district and at each school related to race, gender, socioeconomically disadvantaged (SED), English learners, and students with special needs; an analysis of prior districts reports related to past attempts to address educational inequities; Stakeholder interviews with current and former district employees, students, parents and community members, as well as all current OUSD school board members; and school site reviews intended to serve as a method for understanding the systems, structures, practices and processes currently used by to support student learning. The site reviews were in many ways the most important part of the equity study. They included extended interviews with principals, focus groups with a sample of teachers, classified staff, and students, and classroom observations. A total of 545 classrooms were observed during the course of the review, which took place over six months.

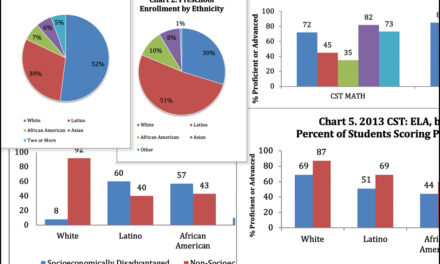

OUSD serves approximately 11,000 students at its 10 elementary schools, two middle schools, one K-8 alternative school, one 6-12 secondary school, one high school, and one alternative (continuation) high school. Another 800 students are enrolled at preschools in the district. In grades K-12, the ethnicity/race distribution has been fairly consistent for the past 6 years. Currently it is: 51.3% White, 29.6% Latino, 6.5% African American, 5.8% Asian. 5.4% of children identify with two or more racial/ethnic groups. At 51%, Latino students make up a much higher percentage of the preschool population than their percentage of the K-12 population. White children make up only 29% of the preschool population. (See Charts 1 and 2.)

Twenty-nine percent of OUSD students are classified as socioeconomically disadvantaged (SED). The differences in the percentage of SED classification between ethnic groups is large: 60% of Latino students and 57% of African American students are SED while only 10% of Asians and 8% of Whites are identified. Latinos make up 30% of the district-wide population. However, they represent between 40 and 76% of the student population at the four schools with the highest rates of socioeconomically disadvantaged students. While Whites represent 51% of the district population, they are under-at the four schools with the lowest poverty rates.(See Chart 3.)

Across all preschool sites, 51% of students are Latino, 29% are White, 10% are African American, 8% are Asian, and 1% are Native American, Native Hawaiian, Alaskan or Pacific Islander.

A 3-year average API was produced in May 2014 before the change in testing took effect. All but one of the OUSD schools with valid scores exceeded the statewide target API of 800 on their school-wide score. Over the past decade, the schools have performed well, and progressively better, according to their API. In 2006, six of 16 schools with valid scores, performed below 800. By 2008, 15 schools with valid scores performed above 800, and only Oceanside High School performed below 800.

Despite this progress, all of the schools posted large gaps between groups.

2013 CALIFORNIA STATE TEST: ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS and MATH

Across the district, 75% of students scored at proficient or advanced on the ELA CST (See Chart 4.)(See Appendix 2. Chart 14). However, a closer look reveals wide disparities by ethnicity/race. These are exemplified by the 52% proficiency rate for African American students and 58% proficiency rate for Latino students. Further disparities within the ethnicity groups exist between SED and non-SED students (See Chart 5.). Girls outperform boys in both groups; African American girls outperform boys 56% to 46%, and Latino girls outperform boys 60% to 55%. Only 55% of students identified as SED demonstrated ELA proficiency. The outcomes in math were lower across the district, and high school scores were significantly lower than elementary scores.

On the Math CST, 62% of students scored proficient or advanced (See Appendix 2. Chart 15). As is true with ELA, disparities between students from different ethnic backgrounds are persistent and pervasive. Whereas the district average proficiency is 62%, the proficiency rates for African Americans (35%) and Latinos (45%) are far below that of their White (72%), and Asian (82%) peers. The subgroup with the lowest rate of proficiency is Students with Disabilities (36%), followed by Socioeconomically Disadvantaged students (42%). Within ethnic groups, females outperform males in most groups by as many as 9 points (African American), and non-SED students outperform SED students in all groups by as many as 23 points for students who identify with two of more races to a 13-point difference for African American and Latino subgroups (See Chart 6.).

Results of the baseline CAASPP indicate that achievement gaps exist for African American, Latino, English Learners, SED, and SWD across the district. There is a 35-point achievement gap between African American and White students, and a 30-point gap between Latino and White students. Only 44% of African American and 49% of Latino students met or exceeded standards, while 83% of Asian and 79% of White students met or exceeded the ELA standards. The differences by socio-economic status are also striking: 71% of non-SED students met or exceeded standard, while only 50% of SED students met or exceeded the ELA standard. Latino students who are also poor (SED) fared even worse: only 40% met or exceeded the ELA standard. Sixty percent of socioeconomically disadvantaged White students met/exceeded standards in ELA and fifty-seven percent of all tested students met or exceeded math standards on the CAASPP.

Classroom observations that were conducted as part of the equity review revealed that most teachers throughout the district did not utilize strategies aimed at engaging students in deeper learning. Instead, we observed students who were generally well-behaved but expected to listen passively to lectures in nearly every classroom. Focus groups with students revealed that most students felt insufficiently challenged and were frequently bored even in honors and advanced placement courses. The fact that achievement rates were high, especially among White and Asian students, was attributed to the hard work of students and the fact that many received external support outside of school from parents and private tutors.

Interviews with teachers revealed that district efforts to improve teaching and learning were sporadic and inconsistent. Most schools lacked a coherent strategy for supporting teachers, which many attributed to the high turn over in district leadership. We learned that at many of the schools, non-evaluative classroom observations were rare because principals and district leaders were preoccupied with managing the demands of parents and other constituencies. Additionally, at most of the sites, professional development was not tailored to address the specific needs of teachers. Instead, the focus of professional development changed each year without any clear explanation of why.

While the results of the research in OUSD was largely disappointing, when the findings were shared with teachers and principals throughout the district they enthusiastically welcomed the opportunity to change the focus of practice. Though some asserted that large class sizes made it difficult to utilize more engaging pedagogical strategies, the majority welcomed the opportunity to shift to a focus on deeper learning. One veteran teacher explained her response to the equity report in this way:

This study confirmed what I have assumed for many years: we’re not pushing our students to think very hard. When I hear that many are bored because we lecture too much I feel embarrassed. I didn’t go into teaching to talk. I became a teacher to inspire my students and clearly this is not what we’re hearing is going on. I believe that we can do better than we have and this study has shown us that we better if we want to retain the confidence and support of our parents (May 14, 2016).

It must be pointed out that while there was little opposition to the findings from the equity report, changing the culture of schools will take time and it will be challenging. Shortly after the release of the report the superintendent of OUSD and four principals (including the principal of the high school) resigned. While the new administrators have professed a willingness to follow through on the recommendations of the report it is clear that the structural obstacles that have contributed to the isolation of teachers are still present. Moreover, at several of the schools there continues to be a lack of clarity about the role and purpose of professional learning communities. Until such obstacles are addressed throughout the system, progress in reducing disparities, particularly those that are correlated with differences in race, language and income, through the implementation of changes in teaching and learning will take time to achieve.

DEEPER LEARNING COMES TO BROCKTON

With over 4,200 students, Brockton High School is by far the largest high school in the state of Massachusetts. Like many urban high schools it had struggled for a number of years with high dropout rates, serious discipline infractions, and poor academic performance generally. The school and district leadership had for many years taken the position that little could be done to improve the school because of the large number of poor and disadvantaged students it served. The city of Brockton is like many formerly industrial, economically depressed cities in the northeastern region of the United State and the rust belt, with high rates of intergenerational poverty, unemployment, crime and substance abuse.

A broad variety of educational programs (e.g. interventions to support at-risk students and academic supports that were largely remedial) had been implemented in the past and were available at the school but there was little focus on ensuring that these programs were effective and that they were actually meeting the needs of students. Administrators at the school were accused of having a passive approach toward the academic challenges facing the school, and many teachers took the position that it was up to the students to take advantage of what was available. One long time principal of Brockton High School often told the faculty that, “students have a right to fail”.

The student population of Brockton HS is racially and socioeconomically diverse. Approximately 60% of the students are identified as Black but this grouping includes African-Americans, Cape Verdeans, Haitians, and many other immigrants from countries around the world who do not speak English as their first language. 22% percent of the students are white, 12% are Hispanic, 2% multi-race, and 2% Asian. 17% of students are classified as Limited English Proficient, and 11% receive special education services. Overall, approximately 40% come from families that do not speak English as their first language. 76% of students at the school come from families in poverty and qualify for free or reduced price lunch. The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education classified over 80% of students at Brockton HS as “High Needs.”

In 1998, Massachusetts introduced the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS); a high stakes exam that all students in the 10th grade are required to take and pass (both the English Language Arts and math exams) in order to earn a diploma. When the results of the first MCAS were released, Brockton High was ranked as one of the lowest performing schools in the Commonwealth with a 44% failure rate in English, and only 22% of students receiving scores at the proficient level. In math, the failure rate was 75% with only 7% reaching proficiency. Based on their performance, hundreds of Brockton High students were at risk of being denied diplomas when the state put the new requirements into effect in 2002. When similar results were obtained the following year Brockton High School was featured on the front page of the Boston Globe as one of the worst schools in the state, and described as a “cesspool”. 5

Interestingly, instead of responding to the article with resignation after the school was labeled a failure, the article prompted a call to action. Shortly after the results were released a team of veteran teachers approached the new principal, Susan Szachiewitz, determined to do something in response to the dismal test results. Recognizing that many of the students entered high school with weak literacy skills, and that the math and language arts portions of the exam required strong literacy skills, the teachers argued that every teacher at BHS would have to start teaching and reinforcing literacy in their classrooms. Szachiewitz acknowledged the need to strengthen the literacy skills of students but said that she couldn’t force teachers to embrace this strategy. The teachers responded by stating that they could begin by “working with the willing”.

Calling themselves the Restructuring Committee, they began their first meeting by posting the MCAS scores with a question under them: Is this the best we can be? Initially, the committee thought that it could improve test scores by focusing solely on preparing students for the test. They noticed that in the first three years of testing that there were several questions and readings pertaining to Shakespeare. Based on the assumption that this would continue to be the case they launched what they called a “Shakespearean offensive”, getting teachers throughout the school to teach a Shakespearean text. However, the following year there were no questions on Shakespeare on the MCAS and they soon realized that the “Shakespearean offensive” was a mistake. Reflecting on their error, the Restructuring Committee came to the conclusion that school improvement could never be about outguessing the test or simply preparing by providing students with test taking skills. After closely examining the data from the previous year’s exam they came to the conclusion that their students were struggling in reading, problem solving, vocabulary, thinking and reasoning skills. They also recognized that failure was not limited to any one subgroup. For this reason they concluded that they could not address the problem through remediation to students who were failing. Rather, the data clearly revealed that failure was widespread and therefore, changes in teaching and learning would have to occur throughout the school.

Interestingly, while urban districts in other parts of the state focused on test preparation through pre-packaged courses (Noguera 2004), BHS set off on a path to make deeper learning its “high leverage” improvement strategy. The committee asked a series of questions that helped them to develop and frame their work:

- What are we teaching, how are we teaching it, and how do we know the students are actually learning it? The leadership group recognized that most classes at the school were focused primarily on delivering content. Like most high schools, BHS was compartmentalized into highly structured departments. While many teachers were knowledgeable in their content areas, most taught in a manner that paid very little attention to evidence of student learning: they covered the material and students were expected to learn it. Many other teachers struggled with classroom management and relied primarily on lecture and work sheets. In response to the question about how they knew the students had learned the material, they came to the painful realization that they had not been focused on evidence of learning at all.

- What do our students need to know and be able to do to be successful on the MCAS, in their classes, and in their lives beyond school? This generated what was perhaps one of the richest discussions that the faculty had ever had, and led directly to the development of the school-wide literacy initiative. Teachers identified the essential skills that students needed to acquire to be prepared for the rigorous state exam, and ultimately, college. Based on their review of the state assessments the school adopted a concerted focus on reading and writing in all classrooms with clear rubrics for teachers to use to evaluate and monitor student performance.

- We are not likely to get any additional staffing or resources, so what resources do we have now that we can use more effectively? The faculty committee recognized that time was the most important resource needed to propel their improvement efforts. They knew that a great deal of time during the school day was not dedicated to instruction. Many students had schedules that were filled with one or more study halls. They strategized to figure out how to convert this time into structured learning opportunities. They understood that students had become more engaged in their classrooms and receive targeted support in the areas where their needs were greatest. They also recognized that to increase the time spent on student learning they would have to revise the staff schedule. This meant that faculty would have fewer preparation periods and faculty meetings would have to be used to provide professional development in literacy rather than being used for administrative announcements.

- What can we control, and what can’t we control? They knew that they couldn’t control the challenges facing students: poverty, homelessness, violence, family turmoil, transiency, language acquisition, etc. While recognizing that these obstacles were not insignificant, they decided that instead of using poverty as an excuse and feeling sorry for their students they would to take a hard look at how they utilized external resources (e.g. social services provided by community partners) to support students so that the staff could remain focused on teaching and learning. Shifting the focus of their conversations in this way proved to be the key to the changes that were implemented throughout the school.

The central office in Brockton Public Schools was aware of the strategy that the faculty committee had devised. Initially, some in the central administration questioned where or not an intensive focus on literacy would produce the increase in student test scores that the state demanded. They also questioned whether in a district with a strong union they could compel teachers to be trained so that they could help students to acquire the literacy skills they needed. However, after meeting with the BHS staff over the course of several months and recognizing the value of teacher leadership at the school, the superintendent and central office staff embraced the strategy: every teacher in the school, not just those in the English or math departments (The subjects tested on the MCAS) would be responsible for preparing students to take the rigorous state exam. It is important to note that the success of the strategy at the high school ultimately led the central office to adopt similar teacher-led initiatives at schools throughout the district.

In 2000, the school implemented the Literacy Initiative and clearly defined literacy skills that every teacher would have to teach and develop: Reading, Writing, Speaking, and Reasoning. Within each of those areas, they detailed a series of objectives that every student at BHS would be expected to master. These became the school’s academic expectations for every student, regardless of their background or some preconceived notion of their academic ability.

Drafts of the literacy goals were presented to faculty in small interdisciplinary discussion groups facilitated by members of the Restructuring Committee. Presentations about the initiative were made to the School Board, parents and even to the Chamber of Commerce, to seek their input and to demonstrate that the school was not going to accept its dismal performance. From the outset they understood that each of the skills they identified would have to be applied differently in each content area, and therefore, professional development would have to be adapted and personalized for each teacher. Regardless of the class or subject they taught, they wanted teachers to see the importance of getting their students to master essential literacy skills.

Initially, the teachers union objected to the literacy initiative and supported teachers who refused to participate. In response, the school devised a strategy to “work with the willing,” based on the hope that teachers could gradually be won over to support and implement the initiative throughout the school as evidence of success was obtained. The willingness of the site and district leadership to accept a gradual approach rather than to demand immediate, widespread adoption, proved to be fortuitous. More often than not, school districts adopt a top-down approach toward school reform, and expect schools and staff to comply with orders from the central office rather than working for genuine “buy-in” around a particular strategy.

In Brockton, the literacy initiative was teacher-led, and this was undoubtedly a key factor responsible for the success that was achieved. With its emphasis on using deeper learning as its high leverage improvement strategy, it was essential that the initiative was not driven by the administration but by strong leadership provided by teachers on the Restructuring Committee. Over time teacher leaders won over their colleagues, and rather than resisting change, many teachers admitted that they had never been trained in how to teach reading or writing. To help teachers the Literacy Initiative provided differentiated training to every teacher at the school in how to teach literacy skills in their content areas using a common process, common vocabulary, and a common assessment. They also received training in how to utilize pedagogical strategies in each subject area that would support literacy development and higher order thinking on the part of students, such as Socratic seminars, various forms of group work, and project-based learning.

Using contractual faculty meeting time, the entire faculty was trained over the course of several years in what became known as the Open Response Writing process. The process was developed by the Restructuring Committee and called on teachers in departments to collectively choose texts that were relevant to their content areas in order to provide the context for the writing. Those leading the effort understood that in order to be successful the school needed a coherent strategy, which could only be achieved if teachers implemented similar processes throughout the school. In this way, consistency on that part of teachers would ensure that students would be more likely to acquire the skills that were taught and applied in every classroom consistently.

Once every teacher was trained in the open response writing process, the Restructuring Committee developed a calendar to set the dates for implementation. Teachers in specific departments were assigned a week during which they would teach the writing process to students using their subject area content. Though such an approach might seem highly regimented and at odds with the teacher-led approach, the school opted to do this and to create an implementation calendar to monitor the process and results for two reasons. First, it ensured that every teacher was involved and accountable for teaching the literacy skills through a structured implementation process that left nothing to chance. This ensured that the Literacy Initiative was not treated as yet another fad reform that would be cast aside as other goals became new priorities. Secondly, the implementation calendar ensured that every student would have numerous opportunities for repeated practice of literacy skills. The staff believed that deliberate practice and reinforcement were essential ingredients for mastery, and the Restructuring Committee believed strongly that internal accountability was needed to ensure that these practices were implemented with fidelity in the classroom. Administrators carefully monitored the training of teachers to make sure that each one received adequate guidance and support, and they conducted regular classroom observations to monitor how literacy strategies were implemented. Teachers also met regularly in small groups to analyze the quality of work produced by students and to share the challenges they experienced and the lessons they learned about which strategies were most effective. Utilizing professional learning communities in this way proved to be the most effective means to provide teachers with feedback. The professional learning communities created a nonthreatening setting where the impact they were having on student learning could be assessed. Finally, a rubric was developed and utilized by every teacher to ensure that consistency was maintained in assessing student writing.

As faculty met in interdisciplinary groups to review the work of students, powerful discussions about teaching and learning ensued. By comparing and analyzing student work together they were able to see where there were inconsistencies in expectations, and they debated what sort of evidence was needed to ensure that students had acquired the skills they deemed were most important. In a faculty of over three hundred teachers and with a long track record of failure, there were many who doubted that their students could meet the rigorous standards that were set. However, when teachers who expressed doubts were able to see the quality of writing that students were producing in other classes, they began to understand that high quality instruction and the utilization of deeper learning strategies could directly impact the quality of student work.

Ultimately, true buy-in from teachers came with results, and Brockton experienced dramatic improvement quickly. In the first year of the Literacy Initiative the failure rate on the MCAS was reduced by half, and the proficiency rate doubled (Blankstein and Noguera 2015). Similar results were obtained in the second year, and as it became clear that the progress could be sustained, the voices of the few dissenters were silenced.

The meticulous process used to monitor implementation revealed that some students needed more support, short periods of direct instruction, and regular feedback. Teachers began identifying students who needed more assistance and direction and provided a great deal of one-on-one support during the day when time was available, and after school. Students with Individualized Educational Plans (IEPs) had them revised to include literacy goals, and the supports they would need to reach the standards. A portfolio for every student with an IEP and every English language learner was created to ensure that their progress was monitored.

A tutorial center, called the Access Center, was created to provide individualized support to students and could be accessed throughout the day and after school. Teachers who were willing to provide tutoring assistance to these students were recruited to work in the Access Center. Juniors and seniors were also recruited to serve as peer tutors, and like their teachers, they received training on the writing process so that their tutoring was consistent with the school wide process. Initially, a teacher referral was required for a student to report to the Access Center, but over time, word spread among the students that help was available and the Access Center became perceived as a positive, safe, and supportive place to receive assistance. Within a short time, the Access Center became a place where students sought help voluntarily.

By 2006 the failure rate had been cut in half, and the school had also dramatically improved the number of students that achieved proficiency in math and literacy. In 2009, 78% of Brockton’s 10th grade students achieved either advanced or proficient levels in English language arts (this matched the state percentage) and 60% achieved similar levels in mathematics. Of the 2008 graduates, 97% went on to higher education, with 47% accepted at four-year colleges. For the graduating class of 2009, 98% of Brockton’s students passed the math and English exam by graduation. In 2005, 2006, and 2007 over 20% of Brockton’s graduating seniors were awarded the Adams scholarships (The Adams Scholarships provides tuition support for four years at any state college.), and in 2008, 2009, and 2010 25% of the senior class was awarded the scholarship, the maximum allowed under state program guidelines. The governor of Massachusetts along with the commissioner of education came to Brockton to announce the Adams Scholarship Program in 2005, recognizing the high number of Brockton students who achieved this distinction, especially noting that 35% of these students were minority. The percentage of minority recipients has increased annually, and for the class of 2010, 49% of the recipients are minorities, compared with only 19.8% statewide.

Evidence of progress made it possible for Brockton HS to continue its focus on using literacy to promote improvement over the next decade. They continued to train the faculty in a number of literacy skills using the same differentiated approach to professional development that had been used in the past. Once the faculty felt confident and well trained, the same skills were taught to the students. Workshops themes included: Using Active Reading Strategies; Analyzing Difficult Reading; Reading and Analyzing Visuals; Analyzing Graphs and Charts Across the Curriculum; Developing Speaking Skills; Checking for Understanding; Problem Solving Strategies; Helping English Language Learners Achieve; Teaching Vocabulary in Context. These are the skills and strategies that research has shown are essential for deeper learning (Noguera, et.al. 2015).

Reports on Brockton reveal that success achieved at the high school is gradually spreading to other parts of the district, though progress has been steady and incremental:

- In 2013 the median Student Growth Percentile (SGP) for Grade 10 ELA was high at 73.0. The ELA proficiency rate increased from 67 percent in 2010 to 85 percent in 2013.

- It received four Bronze Medals (in 2008, 2010, 2012 and 2013) as part of the Best High Schools Rankings by US News and World Report. It has also been recognized as a National Model School by the International Center for Leadership in Education for 11 consecutive years (2004-2014).

- The 2012-2013 Brockton Public Schools (BPS) strategic goals for learning and teaching identified writing as a key instructional focus in response to student achievement data and the district has provided professional development to all schools during the 2012-2013 school year to train teachers on how to use various modes of writing: narrative, expository, persuasive and research.

- Teachers throughout the district have writing resources in content areas. For example, the Science Writing Binder for grades 6-8 is a resource that includes writing standards, templates, explanations of the 6 + 1 Traits and writing resources for the four modes of writing, including rubrics and writing prompts.

- The district reaches out to parents through the Community Schools Program, the Parents Academy, which offers workshops of all kinds, and Coordinated Community and Family Engagement of Brockton.

- Resources for homeless families listed in great detail on the Brockton Public Schools website include a variety of community social services. In addition, businesses and organizations such as Wal-Mart, W.B. Mason, Good Samaritan Hospital, and Stonehill College provide materials, services, and clothing for these families.

- The district has established partnerships with outside agencies and businesses to support the work of the schools.

It is important to reinforce the point that the turn around at Brockton High School was not quick or easy. Rather, it was made possible by a steady focus on ensuring that teachers had the ability to teach a full range of literacy skills by using strategies that developed higher order thinking skills among students. There was also a genuine commitment to support and guide teachers, and to tailor that support to the individual needs of teachers, as they engaged in practices that were new and that many teachers found difficult. Finally, there was a willingness to regularly analyze student work to ensure that there was concrete evidence that the strategy was working. The improvement strategy has been sustained for nearly two decades, and schools have replicated the Brockton strategy across many districts and states.

Essentially, there were four steps in the development of the Brockton Literacy Initiative:

1. Empower a Team. The Restructuring Committee served as a think tank where ideas and strategies could be developed and discussed. It provided a context for shared leadership of the work and created a setting where teachers could voice concerns about the process. Importantly, what started out as a mission to improve test scores evolved into a more comprehensive focus on using deeper learning to guide the school’s improvement.

2. Focus on Literacy.Too often, school improvement efforts embrace too many goals that shift from year to year. The literacy work at Brockton HS became the “high leverage” intervention that the school relied upon to bring coherence and consistency to the work of teachers, and to guide student learning. Research on school improvement shows that such an approach has the greatest likelihood of success (Bryke et.al. 2014).

3. Implement with fidelity. Faculty were trained, and required to implement the literacy skills according to a calendar so that students received the deliberate practice needed to master a skill. Implementation of the strategies at the classroom level was carefully monitored, and teachers and students who struggled received sustained support.

4. Monitor, monitor, monitor. Administrators at Brockton HS meticulously monitored every aspect of the process. They made it easy for faculty and our students to obtain help and they solicited their feedback on how things were working over time. By establishing school wide standards, ensuring that students knew what excellence looked like, and designing mechanisms for regular feedback, the faculty was able to establish consistent standards for all students.

Teaching all students the literacy skills in Reading, Writing, Speaking, and Reasoning, worked in preparing them for success on state assessments and in their classes, for college, for work, and for their lives beyond school. Improving the quality of instruction was the driver of the school’s improvement. As the faculty learned to teach differently they maintained a focus on evidence that students were obtaining the literacy skills they needed

By 2010 90% of students at Brockton HS were passing the state exam, and one third of the senior class earned proficiency in math and literacy (Noguera et.al. 2015). These students were entitled to the Adams scholarship, a financial reward that covers the cost of tuition at any public university in the state. These results have now been sustained for the last seven years and Brockton High has been transformed from a school labeled as a failure to one recognized as a national turn around model. Most importantly, as district leaders became clear about the factors that had produced the changes at the high school they began implementing similar strategies at schools throughout the school district.

Eleven years after the school had been labeled a cesspool the Massachusetts Commissioner of Education, Mitchell Chester, was quoted saying the following about the school in the Boston Globe:

“To me, Brockton High is evidence that schools that serve diverse populations can be high achieving schools. It’s just very graphically ingrained in my mind after having walked through the building and gone into classes that there’s a culture of respect among students and adults. You don’t see that in every school”. (June 3, 2009)

On October 9, 2009 Boston Globe reporter James Vaznis began his article entitled Turn Around at Brockton High with the following statement:

“Brockton High School has every excuse for failure, serving a city plagued by crime, poverty, housing foreclosures, and homelessness … But Brockton High, by far the state’s largest public high school with 4,200 students, has found a success in recent years that has eluded many of the state’s urban schools: MCAS scores are soaring, earning the school state recognition as a symbol of urban hope.”

Brockton HS was selected as a National Model School by the International Center for Leadership in Education for eleven consecutive years, as a Secondary School Showcase School by the Center for Secondary School Redesign, for a National School Change Award by Fordham University, and for four years it was awarded a Bronze Medal by the U.S. News and World Report as one of America’s Best High Schools. Harvard University’s Achievement Gap Institute also featured the school as a model, and its’ accomplishments were highlighted by former Governor Deval Patrick in his State of the Commonwealth Address.

DEEPER LEARNING IN THE DEEPER PART OF HELL

In the winter of 2016, I was invited to visit Washington High School, large urban school that was part of a struggling school district in northern California to meet with the administration. The purpose of the visit was to engage in a conversation about the many challenges confronting the school, and to offer suggestions on how they might go about addressing them. The meeting started with the administrators sharing a bit of information about their backgrounds. I was surprised to learn that nearly every member of the leadership team, including the principal, had attended Washington HS as a student, and they continued to live in the community – Del Pacific Hills (DPH), by choice. Several had formerly been athletes at the school and they spoke with pride about the school’s accomplishments in basketball and football. The one administrator who was not from DPH was a former math teacher who had been recognized as a Teacher of the Year by the state three years ago.

Despite their pride, they spoke openly about the many challenges facing the school: low student achievement in all subjects, low graduation rates (though they had been rising in recent years), low A – G (the courses required for college admission) completion rates, and chronic truancy. Having worked with under-performing schools for many years, the challenges they described were unfortunately, familiar. However, what struck me as different about this team of administrators was their deep commitment to the students and the community. Their commitment to improve the school was rooted in their commitment to the community. I had no doubt that their desire to provide better educational opportunities to the students at Washington HS was sincere.

However, while their commitment was strong and their desire to make a difference genuine, the school’s leadership made it clear that they felt overwhelmed by the challenges they faced and were at a loss for what they could do to move the school forward to achieve greater progress. As our discussion progressed the administrators described the enormous obstacles that many of their students faced: inter-generational poverty, families in crisis, homelessness, high rates of interpersonal violence, and a broad range of psychological and emotional difficulties that they described as being related to toxic stress and trauma. They spoke with compassion about these issues but they also expressed their frustrations over the pressure they were under to meet state and district expectations for improved academic performance. The principal put it this way:

“We’re working our butts off to get better but we’re not making any real progress. My team is committed to these kids. We see ourselves in them. But nothing we’ve done so far has produced the kinds of gains the district wants. They’re supporting us but they’re not gonna wait forever for us to produce results.”

The leadership team complained that they had not found ways to address the low expectations of some teachers who they felt used the poverty of the kids and the community as an excuse for failure. They continued to emphasize the school’s strengths: strong athletic teams, many committed, hard working staff, and a culture that they characterized as nurturing and supportive of students. According to the head counselor: “Our kids know we care about them. When the bell rings at the end of the day many of them want to stay up here because they’re safe. They know that at least at Washington someone is looking out for them.”

While they valued the school’s strengths they made it clear that they understood they were not enough to produce the gains in test scores that the district and the state sought. The Assistant Principal put it this way:

“The district wants clear evidence of improvement and they want to see it soon. We feel as though we are making progress, but we haven’t received guidance on how to do this work. We are committed to these kids but the barriers we face are formidable. We’re working hard but I don’t see a clear path forward.”

Sobered by our conversation and the challenges facing the school, I was invited to tour the school and visit some classrooms they regarded as exemplary. Sadly, in nearly every classroom I visited I observed teachers either lecturing or students talking while doing worksheets assigned by the teachers. At the end of the tour, I was invited to observe a literacy circle that was in progress. The circle consisted of twenty-two students gathered around a rectangular table. A poet mentor, a community member who was not a regular member of the staff, who had been hired through a grant to support efforts to improve student performance in literacy, led the class. I sat along the periphery of the classroom as the mentor prepared the students to engage in a writing workshop.

To get the workshop started, she offered the following prompt: “I am not who you think I am.” She then went on to model what she was looking for from the students by explaining that though the students might see her as a professional woman who “has it all together”, she is in fact a single mother who once dropped out of high school, who takes care of several family members, who has a brother in prison, and who struggles everyday just to make ends meet. She offered: “There’s a lot more to me than what you think you see. I struggle everyday just to get by. I’m sure that’s true for some of you too.”

The students embraced the prompt and immediately went to work writing. I walked around the room to observe the students as they wrote. I was impressed to see that several had written more than a page within a few minutes. After about twenty minutes of writing she asked who among the students was ready to share. Several hands shot up immediately. She looked around the room and called on a girl with long braids and glasses who had written over two pages. The girl stood up at her seat and proceeded to read an essay that started like this: “I am not cancer.” She explained that she had recently been diagnosed with cancer and had been consumed with worry about what it meant for her life. She wrote that she had undergone several tests already and made numerous visits to doctors. Then, speaking in a clear, firm voice, she explained: “I will not allow this disease to define me. I am more than cancer. I am a young woman with hopes and dreams. I want to go to college, and eventually, I want to have a family. I will not allow this disease to control my life.”

When she sat down after reading the essay the room erupted with sustained applause, and a few students walked over to hug the girl. The poet mentor then asked for another volunteer and more hands shot up. This time she called on a tall young man wearing athletic gear. He laughed as he spoke which led me to assume that his laughter meant he was not taking the activity seriously. However, after hearing just a few sentences from his essay I realized this was not the case.

He began “I am not a homeless kid that no one loves, even if my mother kicked me out of her house and attacked me.” He proceeded to tell a wrenching story about how he and his brother were expelled from their home by their mother and her boyfriend. He described how his clothes were ripped from his body and how he and his younger brother had to walk through the streets in the dark, barely clad, to their grandmother’s home. He read his story carefully, slowly enunciating each word as if he were reading a report written by an observer to the incident. After he finished his two page story he smiled broadly and sat down. Once again, there were applause and several students walked over to the young man to offer hugs, and words of sympathy. I realized then that his smile had nothing to do with his story or his feelings about the incident.

The literacy circle continued like this for another thirty minutes. Repeatedly, several students raised their hands to share their work. In each case, the stories conveyed personal experiences with hardship, and in some cases, hopes and aspirations for a better life. When the bell rang indicating the end of class, several students walked out exchanging hugs with the poet mentor and their classmates. As they filed out of the room the poet mentor thanked the students for sharing their stories and told them that when they met in the following week they should bring their essays with them. She admonished them: “This was a great start but we don’t do our best work on the first draft. Bring your essays back with you when we meet next week so that we can work on the vocabulary and the writing. I want you to be able to share your stories with others and I want your work to be excellent”.

Struck by the intimacy I witnessed among the students, I asked one of the students if she knew the other students who participated in the class. She explained “Kind of, but it’s not like we’re friends or anything. I mean we see each other at school but I barely know some of the people in here.”

I’ve chosen to share the observations from my visit to Washington High School as the final case study in this paper on the potential of using deeper learning as an intervention for change in schools because I believe it offers concrete lessons for addressing the limits and possibilities of education in distressed communities. During my visit to the school I learned that the students used another name for their community Del Pacific Hills – DPH. They called it the Deeper Part of Hell. A student explained that the moniker came into being after several students had been killed in drive-by shootings in 2011. Several of these students told me that they hoped they would one day escape DPH because the community offered nothing but tragedy and hopelessness for them. One girl, a senior with short hair and a big smile, elaborated: “This is not a place where you want to live and raise a family. There’s too much violence here. All of us are hoping that one day we can get out, but the truth is many of us will probably be stuck here for the rest of our lives.”

The experience of students and staff at Washington High School illuminates the opportunities and challenges for using deeper learning as a high leverage strategy to promote change and improvement. During my short visit it was clear that while the administrators at the school were deeply committed to their students and serious about their desire to do whatever it takes to improve the school, they were at a loss over what they could do. Simply working harder to raise student test scores, the primary evidence that the district and state demanded, had not resulted in any tangible progress. According to the site administrators, progress had been made in improving the culture of the school, but improvements in student learning outcomes (as measured by test scores) had been negligible. Undoubtedly, the school’s lack of progress on standardized tests could be attributed to many factors: low teacher expectations (and low teacher morale), a lack of resources to address student needs (e.g. social workers capable of providing case management for the neediest students, teachers in core subjects capable of delivering instruction to English learners, etc.), and the weak academic skills of many students. The literature on the “science of improvement” identifies all of these factors as essential to efforts to change student outcomes (Bryke, et.al. 2015).

It is important to note that many of the adverse social conditions present at Washington HS and in DPH were also present in Brockton. Both schools serve impoverished populations and lack sufficient resources to address the challenges that accompany economic disadvantage. However, unlike the educators in Brockton, the administrators at Washington did not focus on changing the nature of teaching and learning even though they were desperately searching for a path to move the school forward.

Meanwhile, the poet mentor who was not even a regular employee of the school had found a strategy to get students deeply engaged in learning. By asking students to write about their lives she created a supportive classroom environment and got her students writing. Research on trauma shows that strategies that build a sense of community, foster positive relationships and provide social and emotional support to students in need, are also highly effective at addressing the effects of toxic stress (Raver et.al. 2008). Similarly, research on literacy development shows that the strategies utilized by the poet mentor – revise and re-submit, can be highly effective in improving the literacy skills of students (Christenson 2000; Lee 2007). Once they completed their first draft she was in a position to get them to improve the quality of what they produced. The poet mentor explained:

“These kids have a lot to say, if we just ask them to share. Many of them are carrying heavy burdens that prevent them from focusing on school. Once they see that they can write about their lives they start to see writing as an extension of oral communication and they begin to embrace it. As they do they start writing a lot more. It’s not like what they write is perfect. But who writes perfectly on the first draft? I want them to see writing as a process of communicating what you think as clearly as possible.”

Imagine what might be possible if the administrators were able to see and appreciate the powerful learning opportunities that were created in that classroom? What would happen if similar learning opportunities were available in classrooms throughout the school? Sacramento Area Youth Speaks (SAYS), a writing program established at UC Davis, utilizes this kind of approach to develop writing and other literacy skills in all subject areas. Existing research shows that it is highly effective at getting students to utilize their higher order thinking skills (Watson 2011). Sadly, in too many schools, students regarded as slow or in need of remediation, are denied access to instruction that calls upon them to utilize such skills (Noguera, et.al. 2016).

By inviting students to write about their lives the poet mentor created a context in which deeper learning through writing and sharing was possible. As I glanced at the papers of the students in the classroom I noticed several misspelled words, run-on sentences, and lots of poor grammar. However, what impressed me about their writing was the fluency and ease with which students put their ideas on paper. When I spoke with the administrators about the school’s challenges they stressed the need to raise student achievement. However, they never mentioned the need to increase student engagement in learning. How was it possible that they failed to see the connection between engagement and achievement? Why is it that many schools, even affluent schools like those described in the first case study in OUSD, disconnect their efforts to raise student achievement from teaching strategies that get students engaged and provide access to deeper learning? The administrators at Washington HS told me that most students were well behaved but they complained that many of them were struggling to pass their classes. Unlike the teachers at Brockton High School, their concerns focused on achievement outcomes as measured by grades and test scores. They had no strategy for getting students motivated to learn nor had they enacted a process or strategy that would lead to better outcomes.

FINAL THOUGHTS ON TAKING DEEPER LEARNING TO SCALE: FROM NCLB TO ESSA

Throughout this paper I have focused on the need to expand access to deeper learning as a primary equity challenge. Research has shown that developing higher order thinking and skills such as analytical writing, research and problem solving, may be the key to increasing college readiness and providing students with greater access to high wage jobs (Noguera et.al. 2016; Belfanz 2013; College Board 2017). Such an effort is especially important for students who have historically been deprived access to high quality instruction and a rigorous curriculum, namely English learners, special education students, poor and minority students generally. While few argue with the goals of deeper learning or the need to make the kinds of teaching and learning practices that foster it available to a broader number of students, it has not been the central focus of state or federal policy. Moreover, even when such practices are evident in a single school, taking them to scale throughout a district or state is extremely complex and difficult. While many districts may recognize the need for this type of change, it is not clear that they are able or willing to undertake the time and work involved I scaling up.

As the Brockton case illustrates, the complexity inherent in such initiatives lies in the need for staff to have time to engage in deeper learning themselves. Many districts might want to follow the Brockton example, however they will only experience similar success if there is a willingness on the part of central district staff to engage in a protracted effort to build professional capacity over time (Hargraves and Fullan 2012). It is important to recognize that this is a long-term strategy and not a quick fix. It is not reasonable to expect district staff who have been accustomed to teaching in traditional ways (e.g. teacher-centered, with heavy emphasis place on rote learning) to embrace and successfully implement new strategies quickly. As the OUSD case illustrated, even when district staff appear willing to take on an important social issue (i.e. the achievement gap), knowing what they must do differently to obtain different results is another matter altogether.

Most of the popular reforms pursued over the past few years – site based management, data-based decision making, or value-added measures of teacher efficacy (to name just a few), have done little to change the nature of teaching and learning. Those that have relied on pre-packaged curricula – open court, phonics-based reading, etc., did very little to alter the fundamental problem facing many American schools: the mismatch between the learning needs of students and the skills (or lack thereof) of the faculty who teach them. Closing that gap through a concerted effort aimed at building the professional capacity of teachers is the only way to ensure that deeper learning opportunities will become more widely available.

Both the OUSD and Washington High School cases illustrate how easy it is for those in leadership to fail to see the need for a protracted approach to capacity building. In both cases, district and site leaders wanted to see greater equity in student achievement but they were unclear about what would be required to bring such changes about. The same could be said of some of the well-known reformers who have led the efforts to bring change to urban school districts (e.g. John Deasy in Los Angeles, Joel Klein in New York, and Michelle Rhee in Washington DC). Like the district leaders who thought they could simply apply pressure on Washington HS to obtain improvement, many reformers have exhibited a similar lack of understanding of how schools must change and a high degree of impatience. While there is indeed a need for urgency in addressing the needs of under-served students, pressure and blaming educators who cling to practices and policies that maintain the status quo (Klein 2015) is unlikely to bring about improvement.

To by-pass opposition the reformers have wholeheartedly, and often uncritically, embraced technology, or called for expedited means to remove teachers deemed to be ineffective. While there is some evidence that creative applications of technology may be helpful in supporting student learning (Darling Hammond 2014), tools such as I-pads and software that are used to promote and facilitate personalized learning, are too often treated as a new panacea and fail to address the larger issues related to professional capacity because the districts that embrace them rarely invest sufficient time in teacher training (Cuban 2003; Fullan 2015; Bryke et.al 2015).

Combined with widespread closures of struggling schools and a push to open charter schools, reform leaders have been heralded as innovators and agents of change though more often than not, they have typically paid scant attention to the hard work involved in improving the quality of teaching and learning in the classroom. The evidence shows that for a variety of reasons, the churn of reform has done little to produce sustainable change. Instead, the reforms carried out over the last twenty years might be more aptly characterized as little more than “spinning wheels” (Hess; Payne 2011).

For a variety of reasons, policymakers and reformers have typically ignored the importance of implementing instructional strategies that foster critical thinking, problem solving, analytical writing and deeper learning. Such strategies require a higher level of buy-in from teachers and students, and few districts demonstrate the patience or willingness to adopt a strategy that will not generate quick results. Ironically, although strategies like those used in Brockton are relatively cheap (they can be implemented without much reliance on technology at all) they are less likely to be embraced unless superintendents and policy makers place greater emphasis on the process of change instead of merely demanding better results.

My experience has taught me that shifting the approach taken to school improvement will not be easy. To illustrate this point and to further explain why we can expect significant resistance to using deeper learning as a change strategy, it may be helpful to share an encounter with a former high-ranking state Commissioner of Education. I was invited to accompany a group of educators who were part of a performance-based consortium of schools to meet with the Commissioner. We wanted to use the meeting to share findings from a recent study that had been done on schools in the consortium. The schools had been operating on a waiver from high stakes exams (in every subject except for math) from the state since 1992. 6 Findings from a multi-year study showed that students from consortium schools out-performed students from similar backgrounds on SAT/ACT exams, had had higher graduation and college admission rates, and were less likely to be placed in remedial courses while in college (Performance Assessment Consortium 2013). The results for the 38 schools in the consortium seemed compelling and as such, we asked the Commissioner to allow more schools to join. The Commissioner commended the schools for their accomplishments but then explained that he would not support expansion because he couldn’t trust other schools to implement performance-based assessment effectively.

The Commissioner’s response is indicative of the way many policymakers have responded to calls for using deeper learning as a reform strategy. In an analysis of the opposition, Jal Mehta, a professor of Education at Harvard, has suggested that advocates of deeper learning have a “race problem”. He points out that the practice of “deeper learning in the U.S. is much more likely to occur in predominantly white, affluent schools than in schools serving low-income students of color”. He suggests that many educators and civil rights advocates have been skeptical of calls for deeper learning because they fear it will prevent students from acquiring basic skills. He explains that as a result of this fear “…students in more affluent schools and top tracks are given the kind of problem-solving education that befits the future managerial class, whereas students in lower tracks and higher-poverty schools are given the kind of rule-following tasks that mirror much of factory and other working class work” (Mehta 2014).

There is considerable evidence that Mehta’s point is valid. In both traditional public schools and many charter schools that serve poor children of color there is an assumption that children from disadvantaged backgrounds learn best in highly structured classrooms that rely heavily on strict discipline and teacher-centered direct instruction (Whitman 2008; Marzano 2007; Lemov 2010). Such assumptions have led proponents of reform to resist, and in some cases belittle, progressive approaches to teaching and learning. Instead, they have championed highly regimented approaches to teaching and learning (Lemov 2010), and called for policies broadly labeled “no excuses” that utilize highly prescriptive approaches to teaching and tight controls on student behavior as the primary lever for improvement.