A Legacy of Crisis

Farmer Solutions, Corporate Resistance

by George Naylor and Bert Henningson, Jr.

Ames, Iowa

|

|

|

|

|

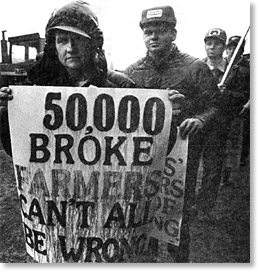

1933 farm auction protest near Denison, Iowa. (Iowa State Historical Department)

|

|

|

|

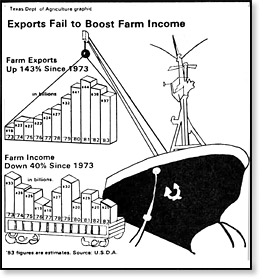

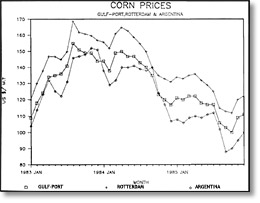

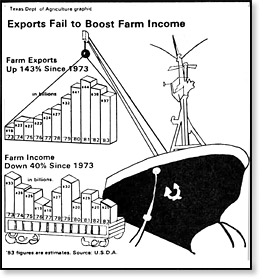

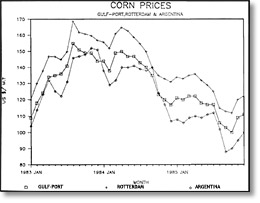

Exports fail to boost farm income. Click to see larger version.

|

|

|

|

Cargill's elevators in Duluth, Minnesota. Photo by Carol Hodne.

|

|

|

|

Exporting nations will undersell U.S. price no matter how low. (FAPRI) Click to see larger version.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

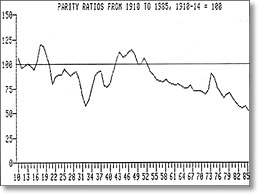

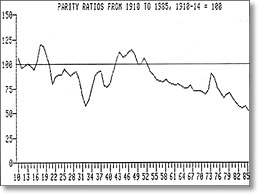

Farmers received 100 percent of parity 1942-1952 because it was the law of the land. Click to see larger version.

|

|

|

|

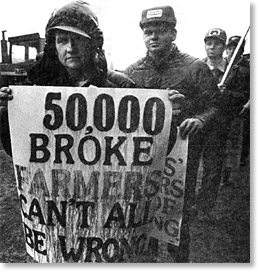

Farmer-Labor Solidarity in the Iron Range of Minnesota, November 1983. (Mesabi Daily)

|

This article (and also Farm Bill Basics) was originally published in 1986 as part of a supporting booklet for The United Farmer and Rancher Congress. The booklet was edited by George Naylor, then education director for the North American Farm Alliance (currently/2007 president of the National Family Farm Coalition). Contributors were Merle Hansen, president, North American Farm Alliance; Dr. Bert Henningson, Minnesota Farmer-Labor Association; Jim Dubert, Iowa Public Interest Research Group; Carol Hodne, executive director, North American Farm Alliance; Dr. Curt Stofferahn, North American Farm Alliance.

The United Farmer and Rancher Congress “Strengthening the Spirit of America” was held September 11-13, 1986 in St. Louis, Missouri and was sponsored by Farm Aid. The Congress was attended by 2,400 delegates from around the U.S. who were selected at grassroots meetings.

Throughout U.S. history, many people have agreed that agriculture is the foundation of our society and economy. Without food to nourish our people and the economic activity surrounding its production, processing, and distribution, the nation would grind to a halt. But like any foundation, agriculture is at the bottom of the structure and is often the least appreciated and most taken for granted. To understand what we can do to save the family farm in the 1980s,we need an historical overview of agriculture's place in our industrial economy and farmers' political responses in previous generations to bring about needed reforms.

During the late 19th century, farmers found themselves exercising less control over the marketing and pricing of their commodities as industrial and financial barons rose to greater positions of dominance in the economic, political, and social order of the U.S. This powerful new generation of entrepreneurs sought monopoly control of their industries and bought political influence and favors in city halls, legislatures, Congress, and the courts. (1) In contrast, the Industrial Revolution placed agriculture in a more vulnerable economic position. The development of a national market economy, controlled from the industrial and financial centers of the country, led to declining commodity prices and rising input costs. Awareness grew that “farmers are the only members of society that buy retail and sell wholesale” it also became apparent that as thousands of farmers individually tried to increase yields, the price situation would only get worse.

Historian John D. Hicks quotes a Kansas farmer of the 1880s: "We were told two years ago to go to work and raise a big crop, that was all needed. We went to work and plowed and planted; the rains fell, the sun shone, nature smiled, and we raised the big crop that they told us to; and what came of it? Eight-cent corn, ten-cent oats, two-cent beef and no price at all for butter and eggs -- that's what came of it. Then the politicians said that we suffered from overproduction." (2)

The new industrial society also brought national “booms and busts” periods of loose credit and inflation followed inevitably by financial collapse, foreclosures, and longer periods of economic stagnation. Today's farm crisis and farm activism is not something new. Farm unrest spread in the wake of financial panics in 1819 and in 1837, during the post Civil War currency contraction that led to the depression of 1893, during the economic collapse following World War I, and after the 1929 stock market crash.

Farmers confront the robber barons

In the late 19th century, railroad barons, New York financiers and industrial tycoons opposed the efforts of farm organizations such as the Grange and Farmers Alliance who believed they had the right to seek legislative restraints to prevent further economic exploitation and concentration. Big business successfully fought the agrarian demands for railroad and currency regulation and they destroyed the cooperative production and marketing ventures organized by farmers. Nevertheless, the farmers' efforts and legislative proposals laid the groundwork for more successful efforts in later years. (3)

From price takers to policy makers

The Great Depression of the 1930s devastated rural America and caused agrarian discontent to once again reach a kindling point. Farmers' agitation spread like prairie fire as large masses of farmers decided to take direct action to save their farms and to secure economic justice. By barricading highways to shut down livestock markets, by forcibly stopping foreclosure sales, and by insisting that local lenders exercise leniency, farmers appeared to be approaching a revolutionary state of mind. (4)

Farm state legislatures attempted to curb the radicalism by enacting moratoriums on foreclosures while Washington moved rapidly to provide relief. Farm mortgages were refinanced at reduced interest rates and on deferred payment schedules. Production control programs were established in the Roosevelt Administration under the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act, but they did not immediately increase market prices. Farm groups like the Farmers' Holiday Association pressed for higher prices. The Agriculture Department announced on October 25,1933, with President Roosevelt's approval, the first non-recourse loan on corn. Continued unrest prodded ten Midwest governors at a meeting in Des Moines, Iowa, on October 31, 1933, to demand that the federal government set prices at parity Ievels.(5) Because of the non-recourse loan, corn prices immediately recovered to the loan level of 45 cents per bushel, up from less than 10 cents per bushel. Price supports have been written into federal law ever since. It must be understood, then, that ever since 1933, farm prices have been set in Washington, D.C.

Under continued pressure from organized groups of farmers, Congress adopted a long-range approach to farm policy with the enactment of a comprehensive farm program in 1938. (The 1938 Act and later the 1949 Act, have no expiration dale and have been the foundation legislation for farm programs to this day.) The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 was the first legislation to use the term “parity prices.” (7)

Parity is another word for equality. Parity prices were considered "fair prices" by farmers who were tired of being second-class citizens. Parity prices, in the law, refer to prices which give farm products the equivalent purchasing power as prevailed in the 1910-1914 base period. As production expenses and family living costs increase or decrease parity prices change proportionately. The 1910-1914 base period was a time when both farm and industrial sectors of the economy were prosperous and in balance.

Parity prices, in other words, are prices that are indexed for inflation. The parity price of corn in the base period was 67 cents per bushel. In the mid-1970s, it was around $3 because the costs of farming and family living had inflated substantially since 1910-1914. Likewise, the parity price of corn in 1986 was about $5 because it would take $5 to buy the same goods that cost about $3 in the mid-1970s.

The term “parity ratio” refers to a statistic that indicates the purchasing power of all farm products on the average. The USDA calculates a “prices received” index, which indicates the weighted average of all farm products with respect to the base period 1910-1914. The USDA also calculates a "prices paid" index which indicates the weighted prices of farm production costs and family expenses with respect to the 1910-1914 base period. The parity ratio, then, is simply the ratio of the prices-received index to the prices-paid index. (8) In other words, if the parity ratio is 50 as it is in mid-1986, then farm products on the average can buy only 50 percent of what they would during a period of 100 percent of parity as in the base period 1910-1914 or in the years 1942-1952.

The campaign to establish decent commodity prices won a complete victory by 1942 when Congress established the price support levels at 50 percent of parity. These loan levels remained in effect through 1952. In those eleven years, the average prices paid to farmers were at or above 100 per cent of parity. (The parity ratio was at or above 100.) These successful farm programs raised market prices and thus were not costly to the government, unlike today’s budget busters. In 1957, Representative Harold D. Cooley of North Carolina, Chair of the House Committee on Agriculture, stated, "The Commodity Credit Corporation supported the prices of major storable crops for 20 years prior to 1953, and at that time this program actually showed a 20-year profit of $13 million." (9)

Parity brings corporate backlash

Farmers' demands for economic justice led to the farm program of the 1930s and 1940s but the nation's corporate and financial leaders had always opposed any attempt by the federal government to regulate the price and production of farm commodities. They denounced the farm program as unwarranted interference with a free market economy. Urban industrialists and financiers wanted the low commodity prices that their economic power would have assured. Low commodity prices gave U.S. manufacturers a competitive edge in export markets because cheap food meant lower living costs and, thus, cheaper labor costs. Cheap labor and cheap food were two of the key factors in the rise of corporate power in the U.S. By raising and stabilizing the prices of farm commodities, the farm program promised a more equitable distribution of income and wealth -- a prospect that corporate America viewed with alarm.

The corporate attack against the parity farm program was mounted by domestic processors, suppliers of agricultural technology, and various corporate advocates of export expansion.

Corporate attempts to get Congress to weaken the parity legislation were almost successful in the Truman Administration. With the help of the Cold War hysteria, the parity legislation was destroyed in the Eisenhower Administration with Ezra Taft Benson as Secretary of Agriculture. Export expansionists persuaded Congress to begin dropping the price support levels, arguing that expanded exports and food-aid programs like Food for Peace (P.L 480) would maintain adequate commodity price Ievels. (10)

Exports expand, farm income declines

Instead, the reverse occurred. Even as exports expanded, the purchasing power of net farm income dropped, forcing 2,000 farmers per week off their land. The purchasing power of net farm income (in 1967 dollars) dropped from an annual average of $25 billion during 1942-1952, the parity years, to an average of $13.3 billion annually from 1953-1972. (11) In 1952, after ten years of parity, net farm income was greater than total farm debt. In 1983, after thirty years of declining farm price supports and the parity ratio down to 56, net farm income was less than farm interest payments! (12)

Net farm income temporarily climbed in 1973 as a result of the massive grain sales to the Soviet Union. It fell again, however, to an annual average of $12.8 billion from 1974 1980, even though exports continued to expand. (13) ln fact, while farm exports increased 143 percent from 1973-1983, net farm income dropped 40 percent during the same period. The grain trade, on the other hand, profited enormously from the renewed price instability. Re-establishing price uncertainty in the marketplace enabled commodity traders to reap greater profits from speculation and to strengthen their control over agricultural transportation and processing industries.

The Free Trade myth:

Multinationals free to smash competition; farmers free to go broke

Although export advocates couch their criticism of the parity farm programs in high-sounding rhetoric about free trade, more exports, and efficient production, they are simply obscuring their own self-interests. Since colonial times, agricultural countries have been exploited by industrial countries which sought to obtain raw materials as cheaply as possible.

The primary tool used by industrial countries to dictate the terms of trade with agricultural countries has been the theory of free trade. Arguing that export expansion is the key to prosperity, U.S. and multinational corporations have pressed for the reduction of trade barriers worldwide. In reality, however, free trade works to the advantage of the most economically powerful forces, that is, the multinational corporations based in the industrial countries. Multinationals are big enough to control supply and to create demand, thereby having the power to control pricing at both producer and consumer levels.

The theory of free trade is also destructive because it promotes high volume production at lower profit margins for producers, thereby making it more difficult to use sound agricultural practices. Not only are producers forced off the land, but they are also forced to maximize production through farmland expansion and through the rapid adoption of expensive, yield-increasing technology. The economic pressure makes it difficult for farmers to abandon ecologically sound soil management and other conservation practices as they devote as much acreage as possible to expanding yields in the short-run. Soil conservation and air and water quality fall victims to the system. (14)

Despite the rhetoric, free trade in agricultural commodities is non-existent. State trading is the rule in international commodity markets. In a 1984 study, the Nebraska Wheat Board found that 95 percent of the world trade in wheat involves government assistance as either buyer or seller. (15) In the U.S., the commodities trade is dominated by a few large multinational companies such as Cargill. Continental, Louis Dreyfus, Bunge and Born, Mitsui/Cook, and Andre/Garnac. Ninety-six percent of U.S. wheat exports, 95 percent of corn and 80 percent of oats and sorghum is handled by these companies. (16) Nor does the U.S. government pay much heed to free trade theory if it is inconvenient, as embargoes by Republican and Democratic administrations attest. While claiming to be free traders, the multinational export expansionists are, in reality, arguing on behalf of strengthening their near monopoly power over the marketplace. With price supports for U.S. commodities driven down to rock bottom levels, U.S. farmers are fully exposed to the predatory manipulation of a marketplace stacked against them.

The free traders in agribusiness, in government, and in the nation's universities said that the profit in agriculture could be increased by expanding production in expectation of “more exports.” Farmers' profit margins shrank, however, as rapidly escalating input and interest costs and failing commodity prices forced them to borrow more. As a result, farm debt climbed from $59 billion in 1972 to over $200 billion 10 years later. (17) The free marketers then said the solution to the farm financial crisis was to expand exports further by culling the price support levels even lower. Instead of bringing prosperity to agriculture, the export expansionists brought a severe 1980s depression rivaling that of the 1930s.

The corporate export myth

The "more exports” solution is a myth for two reasons: first, the U.S. already is the dominant supplier of agricultural products. In 1984 we supplied over 55 percent of coarse grain exports, over 70 percent of soybean exports, and over 35 percent of wheat exports -- by far more than any other nation. (18) Because of our dominance, U.S. price determines the world export price. Smaller competitors must always make their price competitive in order to stay in the market. (See chart showing corn prices at U.S. Gulf port, Rotterdam, and Argentina) Generally, the quantities they ship are determined by their governments through political decisions on production policies and determinations on the need for foreign currency earnings. The mountains of foreign debt require mountains of foreign currency to pay off those debts. These countries are often prominent victims of the "international debt crisis."

Low prices for "more exports" backfires for farmers

If world prices and thus export earnings are low, other countries are likely to increase their production and exports even more in order to improve their balance of payments to meet their increasing debt obligations. This is often done at the expense of their own food supply.

According to a recent study prepared for the Joint Economic Committee of Congress, this has been Argentina's and Brazil's exact response. The report states “While U.S. production and exports have been declining, debtor nations in general, and Argentina and Brazil, in particular, have greatly expanded production and, as statistics concerning the increasing incidence of malnutrition in both countries indicate, they have increased their exports even more rapidly than production. In large measure, their success in boosting exports has come at the expense of U.S. farm exports ... Meanwhile, a recent report from São Paulo, Brazil, indicates that the number of malnourished Brazilian children increased by 23 million over the past 10 years. (19)

Therefore, the corporate strategy of lowering U.S. price supports might cut U.S. market share even more, and, without doubt, inflict greater harm on family farmers all over the world, U.S. farmers included. To say that hunger and low farm prices go hand in hand may seem contradictory, but the conclusion seems inescapable. (20)

The second reason the “more exports” solution is a myth is that most economic experts don't even project substantial increases in exports. Iowa State University (I.S.U.) Professor William H. Meyers states, (21) “Projections based on the macroeconomic forecasts of Wharton Econometrics, assuming a movement toward market oriented loan rates in the United States, do not provide a very bright outlook. Even with substantial declines in the value of the dollar and continued low commodity prices, U.S. exports by the end of this decade still do not recover their peak levels achieved at the beginning of this decade.”

Dr. Meyers also warns against the “trade war" strategy proposed by some in the Reagan administration and some commodity groups. He concludes, "It is a fact of life for a major exporter like the United States that export growth is dependent upon growth in total trade. To focus our energies and resources on attempts to get a larger share of the shrinking pie is a wasteful endeavor. It is always easier for the small trader to win such battles.” (22)

The "more exports" broken record

Despite the obvious failure of "more exports,” and even as more family farms go on the auction block, “more exports” is the prescription that hits the agribusiness headlines. The June 16, 1986 cover of Agweek pictures former U.S. secretaries of agriculture Earl Butz, Orville Freeman, and Clifford Hardin the headline reads, “Former USDA secretaries join in trade symposium: U.S. farm economy hinges on strong export markets.”

This shouldn't be surprising. The support for “more exports” by such government leaders, the grain trade, and big business groups is consistent and unrelenting. The headlines on the front page of Feedstuffs reads, “Cargill most visible advocate of change”. (23) It is referring to changes Cargill wanted in the 1985 Farm Bill, namely lower price supports and elimination of supply management. The article indicates Cargill's influence on other groups like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce (USCC).

The USCC, one of the groups which lobbied to eliminate parity farm programs in the 1940s and 1950s, issued a new position paper on the 1985 Farm Bill. According to Feedstuffs. “The paper contains views similar to Cargill's. For instance, USCC said that the government has been too influential in establishing ‘high commodity prices,’ and the price-boosting policies have 'threatened to price the U.S. out of world markets … .' Further, the USCC paper said, the U.S. government should refrain from any crop management programs and take a more aggressive role in promoting exports.” (24)

Conspiracy demystified

When government leaders and corporate think tanks can be so insensitive to the family farmers' plight, it is not surprising that there appears to be a corporate and financial conspiracy to drive farmers off the land. It is difficult to view the displacement of family farmers as a conspiracy, when one considers how openly government and financial leaders take anti-farmer positions. The displacement of family farmers is, in reality, the natural working of an economic system based on control by the wealthy few.

Although some groups blame the farm crisis on Jewish and English bankers, on communists, on Benedictines or on the Rockefellers, wealth and power in the United States are dominated by Anglo-Saxon, protestant, Republican and Democratic corporate elites. Their common goal is making money and the easiest way to do so is by assuring their corporations a constant supply of cheap labor and cheap raw materials.

Generally, this is assured by the sheer size of their market power. Compared to multinational corporations, the millions of family farmers all over the U.S. producing similar products have no market power whatsoever. If, consequently, farmers receive less for their production than their costs, tough luck. If this means that family farmers will lose their farms, small businesses will go bankrupt, and workers will lose their jobs, then high sounding rhetoric and slogans like “more exports” must be profusely fed to the American people so that the corporate victims do not develop political power to achieve parity legislation to challenge the corporate “gravy train”. Likewise, we often hear the victims blamed by saying they “over produced” or were “bad managers.”

Government programs that originally were intended to protect family farms are turned upside down to keep the system producing while family farmers go broke. PIK programs, huge government payments, export subsidies, bank bailouts, a lower minimum wage, and free trade are all touted as big favors for family farmers and other victims of corporate power.

Farmers and labor join hands

Throughout U.S. history, farmers and labor -- the producing class -- have been on the same side of the struggle for human dignity and freedom. Both have experienced severe injustice at the hands of freewheeling tycoons. (25) For more than a century, the corporate doctrine of cheap food and cheap labor has kept commodity prices down and wages low. Today, the corporate attack includes a massive public relations campaign to convince Americans that family farmers and workers in many industries have become surplus commodities no longer needed in a high-tech free market economy.

Corporate rhetoric aside, the so-called free market philosophy is merely a tool to wealthy and powerful special interests who use government to promote their accumulation of excess profits at the expense of everybody else. This is not a conspiracy but the natural result of an undemocratic economic system that has enabled a few to acquire vast wealth and power. Theories of mysterious conspiracies that can never be proven or fully understood only divide farmers and other people who need to be unified to force changes in government policies.

Published in In Motion Magazine October 31, 2007.

|