|

|

|

North Dakota rally, March 1985. Photo by Terry Pugh.

|

|

|

|

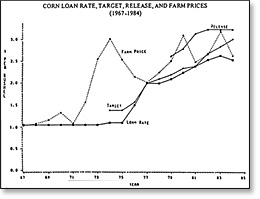

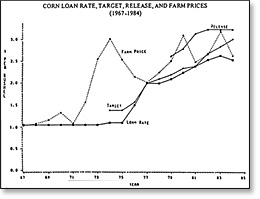

Loan rates set floors and release levels set ceilings on market prices. When these levels are below parity, farm prices and farm prosperity suffer (CARD). Click to see larger version.

|

|

|

|

Kansas farm protest. Photo by George Naylor.

|

|

|

|

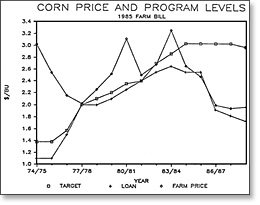

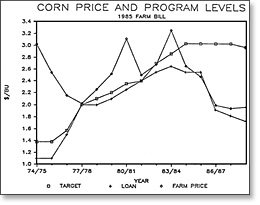

Lower loan rates mean lower farm prices for the duration of the 1985 farm bill. (FAPRI). Click to see larger version.

|

|

|

|

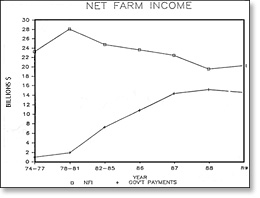

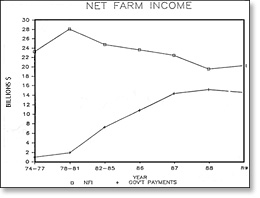

Under the 1985 Farm Bill, income falls and government payments rise to 75% of net farm income. (FAPRI). Click to see larger version.

|

|

|

|

Rev. Jesse Jackson supports Missouri farmers during a protest of the FmHA, April 1984. Borrowers wore brown paper bags to avoid reprisals.

|

|

|

|

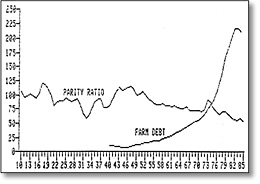

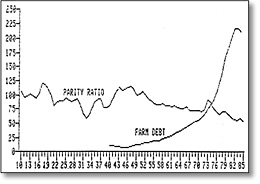

Since 1952, farm debt rose as parity ratio fell. (ISU Extension Service) Click to see larger version.

|

|

|

|

"Give us a fair price and we won't need FmHA." Wisconsin protest October 1984.

|

This article (and also A Legacy of Crisis) was originally published in 1986 as part of a supporting booklet for The United Farmer and Rancher Congress. The booklet was edited by George Naylor, then education director for the North American Farm Alliance (currently/2007 president of the National Family Farm Coalition). Contributors were Merle Hansen, president, North American Farm Alliance; Dr. Bert Henningson, Minnesota Farmer-Labor Association; Jim Dubert, Iowa Public Interest Research Group; Carol Hodne, executive director, North American Farm Alliance; Dr. Curt Stofferahn, North American Farm Alliance.

The United Farmer and Rancher Congress “Strengthening the Spirit of America” was held September 11-13, 1986 in St. Louis, Missouri and was sponsored by Farm Aid. The Congress was attended by 2,400 delegates from around the U.S. who were selected at grassroots meetings.

It's clear that the “more exports” prescription for family farmers is not and never has been a solution to low farm prices. Since the level of farm prices will be determined directly or indirectly in Washington. D.C., It is important that we understand policy tools that can be implemented today by our government to support the family farm system. Without precise understanding of these farm program tools, it will be impossible to forge the political unity necessary to demand that our government support family farm agriculture rather than the interests of cheap exports.

The organized farmers of the late 19th century challenged the monopolistic system exploiting farmers and focused on creating a more equitable society based on cooperative principles. Although the farmers did not attain their goals in the 19th century, a generation later their proposals were enacted into law by Congress. The stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent depression exposed the workings of a monopolistic economy for all to see, generating popular support for legislation designed to assure a more equitable distribution of income and ownership of productive resources. The farm program of the 1930s, under the Roosevelt Administration, gave farmers enough economic and political power to stay on their land and stopped the nation's industrial and financial barons from foreclosing on family farm agriculture.

The basic aim of the farm program was to raise and stabilize commodity prices, thereby Improving and stabilizing the economies of rural communities and preventing commodities traders from manipulating market prices to their own advantage. The key components of the parity farm bill included 1) price supports with provisions to assure a fair share of the market for all farmers, and 2) supply management.

The price support program accomplished its task by establishing a floor under market prices. Farmers in those days knew the price floors had to be the law of the land" before anything would make sense. To balance supply with demand at the price support level, the farm program included a supply management provision to reduce production in an equitable manner guaranteeing each farmer a share of the market based on their production history. The policy tools used to achieve these basic goals should always be contrasted with policy tools that achieve the corporate goal of cheap raw materials.

Price Supports

The primary price support mechanism is the non-recourse ban program administered by the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC), an agency of the USDA. Non-recourse loans, in which the government has no recourse against any of the farmer's property except the commodity under loan, establish a floor price in the marketplace for farm commodities and provide farmers with the leverage to market their commodities in an orderly manner. All farmers who participate in the farm program are eligible to receive non-recourse loans and are thus guaranteed a share of the market. This non-recourse feature enables farmers to forfeit the commodity, which serves as collateral for the loan, and keep the money from the loan if market prices fall below the loan level. If market prices remain above the loan level, farmers sell the grain in the marketplace and repay the loan plus interest to the CCC.

The loan level itself is set by Congress, though the Secretary of Agriculture often has the power to raise of lower it. Ideally, the loan level should be established at 90 percent of parity, as it was between 1942 and 1952. Commodity loans at 90 percent of parity cause market prices to stabilize around the 100 percent of parity level and, since no direct payments are involved, the loan program is self-sustaining and it is crucial to understand that the actual loan level becomes the floor for market prices. Commodity buyers are not able to obtain cheap commodities because farmers simply would forfeit their crops to the CCC instead of selling at market prices below the loan levels. Maintaining the commodity loans at 90 percent of parity balanced the purchasing power of the farm sector with that of the non-farm sector and restrained debt expansion, thus assuring a high level of liquidity in the banking sector.

When export expansionists persuaded Congress to begin dropping the loan levels in the 1950s, market prices also fell. Facing a steady loss of income, farmers were forced to expand their farm operations and to continually adopt yield-increasing technology. The government’s failure to maintain an adequate level of farm purchasing power rapidly accelerated the trend toward larger, more capital intensive agriculture.

Today, the loan levels have been dropped to the 40-50 percent of parity range, driving agriculture into a severe depression. As Iowa farm loader Gary Lamb points out, “A safety net doesn't do much good when it's laying on the ground.” A new device, called the “marketing loan” was designed for the 1985 Farm Bill that does not support prices but actually make market prices fell. The marketing loan, which is in effect for rice and may be implemented for other crops, allows farmers to sell their crop and repay their crop loan at less than the loan level. This destroys the price support mechanism and adds even more to government costs.

Target prices end deficiency payments: corporate formula

The grain trade objects most strongly to the non-recourse loan program which establishes a floor under market prices and prevents price manipulation. Bowing to grain trade propaganda that the price support level had to be lowered in order to expand exports, Congress established a target price program to compensate farmers for the income they would lose as market prices fell to the lower loan levels.

The target price program authorizes direct cash payment, called deficiency payments, for farmers participating in the farm program if market prices fall below the target price. The target price is higher then the loan level, and the deficiency payment equals the difference between the target price and the loan level, if the market price is below the loan level. Otherwise, the deficiency payment equals the difference between the target price end the market price.

Unlike the commodity loan program which operates at minimal cost to the government, the deficiency payments are a direct payment to producers the government never recovers. Since loan rates have been lowered, the target price program is simply a cheap grain for the grain trade. Deficiency payments are export and consumption subsidies for multinational corporations. If the non-recourse loan levels were re-established at 90 percent of parity, the target price program would be unnecessary.

Supply management

Set-asides and marketing certificates are two of the main supply management tools. Set asides work in the same manner as an acreage allotment program. Each producer established a production history with their local Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service (ASCS) office. ASCS, an agency of the USDA, then determines whether or not the supply of any program commodity is likely to exceed Program goals. If so, the Secretary of Agriculture may announce a set-aside program to reduce the production of a specific crop. The set-asides are allocated equitably on the basis of each farm's production history and provisions are available for new producers to establish a production base.

The desired reduction in production is accomplished by requiring farmers who participate in the non-recourse loan program to reduce their production on a uniform percentage basis. Larger farmers, therefore, must place more acres into the set-aside than smaller producers.

A marketing certificate limits the amount of commodity a farmer can sell based on production history. This device can be used in conjunction with set-asides or production decisions can be left up to the producer.

Since the 1950s, the set-side program has not balanced supply and demand because the federal government, influenced by the grain trade's opposition to the farm program, abandoned not only its commitment to adequate price support levels but also to a consistent long-term supply management program.

Once Congress had dropped the price supports to such low levels, many farmers had no incentive to participate in the meager set-aside programs that were announced. In order to obtain broader participation in set-aside programs, particularly during election years, Congress authorized “paid diversions”· for farmers as compensation for a portion of the acres they were to place in the set-aside. These direct payments increased the cost to the government and usually had no effect on market prices.

The Payments-in-Kind, or PIK program, represents another attempt by the federal government to reduce the large commodity stocks which have accumulated because low loan levels and market prices forced farmers to expand their production. In 1983, as an incentive to encourage participation in the set· aside program, the Secretary of Agriculture offered to compensate farmers, not with direct cash payments, but by allowing them a partial payment in the form of grain in the government stockpiles. The intent was to avoid the increased cost of direct cash payments and to reduce the cost of carrying a large government inventory.

A major drought accompanied the PIK program, which lifted market prices but reduced the amount of production farmers had available to sell. In the absence of the drought, the release of government grain stocks under the PIK program would have had a depressive effect on market prices. In any case, PIK was conceived only as a stop-gap measure. The government’s failure to adopt a consistent, long-term supply management program has caused stockpiles to continue mounting while prices slide even further.

The PIK idea was resurrected again in the latest farm program. Part of the deficiency payments is being paid by PIK and it is the general consensus that these payments are simply freeing up government stocks to further depress market prices. Likewise, "export PIK" gives bonus bushels to selected foreign customers to regain their patronage. Again this may tend to have a depressive effect on market prices. (1)

Bountiful harvests should be a blessing

Reserves are an important aspect of supply management. The blessing of a bountiful harvest should not be used as an excuse to break domestic markets or to dump surpluses on the markets of farmers in other parts of the world.

The parity farm programs that were established in the 1930s included provisions for grain reserves called the Ever-Normal Granary; the reserve program authorized the USDA to allow farmers to store their grain for a specific time period and to receive a non-recourse loan as payment for the storage. The federal government built its own warehouses to store forfeited commodities, thus giving the USDA a key role in leveling out the wide swings from glut to scarcity in grain production. Under parity programs, the federal government could not release its grain stocks onto the market if doing so would drive market prices below parity. Farmers, consumers, and livestock feeders were all protected by this system.

When the grain trade persuaded Congress to begin weakening the farm program in the 1950s, however, the government started dumping its stocks onto the market in a manner calculated to drive market prices down. This practice angered farmers and made them suspicious of any attempts to re-establish a government controlled reserve program.

Congress overcame the opposition by enacting a farmer-held reserve in the 1977 Farm Bill. Unfortunately, the farmer-held reserve included provisions for triggering release of the stocks at relatively low market prices. The farmer-held reserve thus became a dumping mechanism that placed a low ceiling on market prices and on farm income.

Parity program worked: It can work today

Farm policy tools abound and no doubt more could be fabricated by corporate bureaucrats. But if the intentions of the government were to benefit family farms, farm programs would not need to be so complex or mysterious.

After five years of experimentation with new farm programs during the early years of the 1930s depression, Congress, in 1938, adopted a long-range comprehensive farm bill with non-recourse loans and supply management as the key components of the program. The loan levels finally were raised to 90 percent of parity in 1942 and farm prices averaged just over 100 percent for the next 10 years.

The obvious reason that farm programs of this period achieved parity for farmers is that parity was what they were intended to achieve. On the other hand, corporate authored farm programs since the mid-1950s failed to provide parity because they were only aimed at providing cheaper commodities, and in turn cheaper labor, for their corporate purchasers.

Also, the parity farm programs had a mutually supportive effect on the rest of the economy.

From economic observations the advocates of parity discovered that each dollar of farm income multiplied seven times in the national economy as it passed from hand to hand in trade channels. Farm commodities valued at parity brought balance back to the economy, creating new purchasing power and economic activity based on the circulation of earned income, not on debt expansion at high interest rates.

Thanks to the parity farm program and other price stabilization measures, the economy was solvent, the dollar was stable, inflation was minimal and no post-war depression occurred, as had been the case after World War I. If every citizen of the U.S. understood the importance of parity to the health of the overall economy, a parity farm program might be the law of the land today.

In the 1985 farm bill debate, the Farm Policy Reform Act sponsored by Senator Tom Harkin of Iowa and Representative Bill Alexander of Arkansas was the closest approach to a parity farm program. It would have raised price supports to 70 percent of parity on most basic storable commodities with further increases in succeeding years, eliminated deficiency payments, and required mandatory production controls after approval by a farmer referendum. The Farm Policy Reform Act would have increased net farm income, drastically cut government costs, and even increased export earnings despite slightly lower export volume. (2) Opinion polls indicate that most farmers today favor similar legislative provisions which clearly represent the interests of family farms rather than the interests of corporate, export-oriented agribusiness. (3) A farm program that strengthens family farms and the whole economy can work today, if that is its intention.

In light of the disastrous consequences of the 1985 Farm Bill, there are renewed grassroots efforts to push for enactment of the Farm Policy Reform Act. New provisions for a dairy program, emphasizing higher price supports and a quota system to assure family farm production, will be included this time.

1985 Farm Bill -- policy upside down

A look at central Iowa harvest bids for corn and soybeans will tell you that the new 1985 Farm Bill isn’t of the parity type. Corn at $1.54/bu. and beans at $4.48/bu. and possibly going lower --both less than 40 percent of parity, can only spell disaster for the majority of farmers. After nearly two years of debate among farm, corporate, agribusiness, commodity, and other groups, President Reagan signed the 1985 Farm Bill, also known as the Food and Security Act of 1985 (FSA 1985), on December 23. 1985. The final version of the bill retains many of the policy instruments in the 1981 bill, but intensifies the pressure for family farmers no matter where they farm or what they produce. Once again, the intentions of the first farm programs have been turned upside down for the benefit of multinational corporations.

Loan rates, which were maintained at a constant level during the previous four years are reduced greatly under the Act to increase U.S. agricultural trade competitiveness. Target prices are also maintained at 1985 crop year levels through 1988, but then are allowed to decline by 10 percent during the remaining three years. Additionally, participants in supply reduction programs are “sheltered" during the transition to lower market prices by deficiency payments lied to target prices. Part of the deficiency payments will be advanced as PIK which will contribute to the price slide to lower levels. The last instrument of note in the bill is the "expanded export provision," also known as export PIK, which permits the use of CCC stocks as payments-in-kind to foreign customers in an attempt to regain their patronage.

The 1985 Farm Bill claims to "move U.S. agriculture to a more competitive position in world markets.” Because loan rates, which act as price floors, will be reduced by 5 to 25 percent in 1986, market prices are predicted to fall. This means direct government payments to producers are expected to rise to $15 billion in 1988, as compared to $8 billion last year. But even with this increase in deficiency payments, net farm income is expected to decline to less than $20 billion over the same period, thus worsening the farm financial crisis, according to another FAPRI report entitled “An Analysis of the Food Security Ad of 1985.” (4) The same report indicates that by 1989, nearly 75 percent of net farm income will come from government payments! FAPRI's conclusions don't include the possible implications of the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings legislation, which could reduce payment levels to program participants by 10 to 30 percent. But the analysis and projections do assume variable growth in U.S. gross national product, moderate increases in inflation, declining unemployment, volatile interest rates, and a depreciating U.S. dollar.

The Food Security Act of 1985 is distinctive in three ways. First, it is the most complicated farm bill yet. Second, It will cost the federal government more than any other farm bill. And third, the price supports, in terms of percent of parity, are set at levels lower than any previous farm bill. In other words, the corporate purchasers of farm products have never received such a good deal.

Credit: no substitute for fair prices

Because of the last thirty years of farm prices aiming for sub-parity prices, farmers substituted credit for earned income, and amassed a total of over $200 billion in debt by 1982. Interest payments became a major farming cost, and on the average were more that net farm income. 5 The downward spiral of asset values, financial stress and the threat of foreclosure have imposed constant burdens on many farm families. Some of these burdens include turning operating decisions over to lenders and begging for money to cover basic family expenses. Farmers who have tried to organize to change these conditions have sometimes been threatened with lender retaliation.

The obvious severity of credit problems has led to increased support for reforming agricultural credit policy in the U.S. The federal government is now considering proposals to spend billions of dollars for emergency farm credit relief. Unfortunately, the proposals for federal action receiving the most attention in Washington are either blatantly unfair or woefully inadequate. One proposal, known as “loan warehouses” would use government money to rescue agricultural lenders, but would sacrifice the farmers. Other proposals would facilitate debt restructuring negotiations between farmers and lenders with a combination of lender forgiveness and government funds to write down loan principal and interest rates. But these proposals are flawed in that many farmers will fail to cash flow even with the proposed principal and interest write downs.

Fair credit plan

A popular proposal among farmers is known as the “Fair Credit Plan,” which would help both farmers and lenders who are in trouble. Payments on money advanced by the government to restructure the debt would be deferred until farm income improved to make the payments possible. This provision would direct public attention to the fact that higher farm commodity prices are necessary to solve the agricultural financial crisis.

We must remember that farm debt wouldn't be a problem today if parity prices had been the goal of recent farm programs. It should be dear that the only real solution to the farm crisis is a fair price.

|